- More on the proposed trustee tax rate increase

- A long-standing over-taxation issue is resolved

- A new tax principles act.

One of the odd things about the budget process for me is that tax really doesn’t feature very much. In fact, I know some very experienced tax practitioners who don’t go to the Budget Lockup because of this. Most of the Budget and the accompanying analysis focuses on the exciting stuff – where the money being spent and the winners and losers from that funding. The source which provides most of that spending is almost an afterthought unless as in 2010 and again in 2017 tax cuts are a centre piece of the Budget mix.

In part, that’s because, unlike Australia and the United Kingdom, the legislation relating to various technical amendments to the Taxes Act is usually introduced separately. It was therefore a bit of a surprise last week when after the budget lockup period ended at 2 p.m., I discovered that there had been not one, but two tax bills published. Other than the announcement of the increase in the trustee tax rate to 39% the budget documents had not indicated there would be many significant measures.

In fact, as the bill’s title explains, The Taxation (Annual Rates for 2023–24, Multinational Tax, and Remedial Matters) Bill, it primarily relates to the introduction of the relevant legislation to support the OECD’s Pillar Two global minimum tax proposal. You may recall the Australian Budget two weeks ago included similar measures. It would have been surprising if we had not followed Australia’s lead although neither the Revenue Minister nor the Finance Minister made much reference to the proposals last week.

Introducing the global minimum tax rate

The intention behind Pillar Two is to impose a global minimum tax of 15% for all those multinationals with annual revenue exceeding €750 million, these are the so-called global anti base erosion (“GloBE”) rules. The legislation and commentary include a heap of new tax acronyms including DIIR (Domestic Income Inclusion Rule), POPE (Partially Owned Parent Entity) and QDMTT (Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax), which a rather cynical overseas tax advisor has suggested should be pronounced Q-Dammit.

The commentary to the tax bill explains the legislation will only take effect once a “critical mass of countries” has adopted the GloBE rules. This is thought to be “very likely, though is not certain”. If that critical mass is reached, then the rules will be phased in starting from 1 January 2024.

Assuming Pillar Two does proceed then how much will it raise? Not much. According to the Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) released with the tax bill the GloBE proposals should be worth $25 million annually with another $16 million coming from taxes on amounts which would have otherwise been shifted to lower tax jurisdictions. The RIS explains this “modest amount” is because of a number of factors including that only 20-25 multinationals will be affected.

Now earlier this week. Facebook’s New Zealand’s accounts were public. And despite earning gross advertising revenue over $154 million its reported profit before tax was just $3.3 million, and it just ended up paying just over $1,000,000 in tax. That’s because it paid over $149 million for the purchase of services to a related company, Meta Platform Ireland Ltd. The GloBE rules are intended to counter this. But don’t expect that they will raise significant sums of money.

Raising the Trustee tax rate to 39%

The headline measure and tax measure in the budget was the proposed increase in the trustee tax rate to 39%, with effect from 1st April next year. Now, this is a conceptually logical move, and as noted last week was one that both Treasury and Inland Revenue recommended should have happened when the personal income tax rate was increased to 39% on 1st April 2021.

The commentary for the tax bill provides some more detail around the introduction of the measure, and a couple of points stand out. One of Inland Revenue’s examples appears to suggest that it would not automatically see allocation of beneficiary income by a trust to someone whose tax rate was below 39% as constituting tax avoidance. At least this appears to be implication from example 20 in the commentary, and that’s caused a few comments from other tax advisers as to whether Inland Revenue is signing off on tax avoidance.

Example 20: Mitigating over-taxation

Amy (an air traffic controller) and Anthony (a builder with his own company) have settled some income-generating assets on a discretionary family trust for the benefit of themselves, their children (both minors under the age of 16) and future grandchildren. Amy, Anthony and their accountant are the trustees.

2024–25 income year

Anthony has personal income of $70,000 and Amy has personal income of $180,000. Their trust has income of $40,000.

If the income is retained as trustee income, it will be taxed at the proposed 39% trustee tax rate. Any income allocated to their children as beneficiary income will also be taxed at 39% under the minor beneficiary rule.

However, by allocating the income to Anthony as beneficiary income, it can be taxed at his personal tax rate. This amount can be credited to Anthony’s current account, available to be called upon at any time, or he can settle it on the trust if he wishes to do so.

2025–26 income year

Barry, the older of Amy and Anthony’s children, has turned 16, so he is no longer a minor. Barry has no personal income. Anthony again has personal income of $70,000, and Amy has personal income of $180,000, while the trust has income of $50,000.

Since Bary is no longer a minor, he is not subject to the minor beneficiary rule. Income can be allocated to Barry as beneficiary income and taxed at his personal tax rate (for example, up to $14,000 at 10.5%, over $14,000 and up to $48,000 at 17.5%).

If the trustees do not want to distribute this income to Barry, it can be credited to his current account, available to be called upon at any time, or a sub-trust arrangement can be set up so that Barry’s interest in a portion of the trust assets is recognised and protected.

On the other hand the legislation specifically counters attempts to distribute income to certain corporate beneficiaries. The benefit here obviously being that instead of trustee income being taxed at 39% it would be taxed at the corporate income tax rate of 28%. The bill aims to negate potential distributions being made to closely controlled family companies.

The bill will not apply to deceased estates but only in respect of trustee income derived within 12 months of the deceased persons date of death. Based on personal experience and discussions with lawyers that 12-month period is too short, 18 to 24 months seems more appropriate

There is also an exemption for disabled beneficiary trusts which are defined as having only one beneficiary other than any residual beneficiaries who may benefit on the death of the disabled person. Critically the trustee must not allow any further beneficiaries apart from residual beneficiaries to be added. I expect that this may mean a number of existing trusts may have to be amended or be re-settled in order to comply.

A end to over-taxation of ACC lump sums

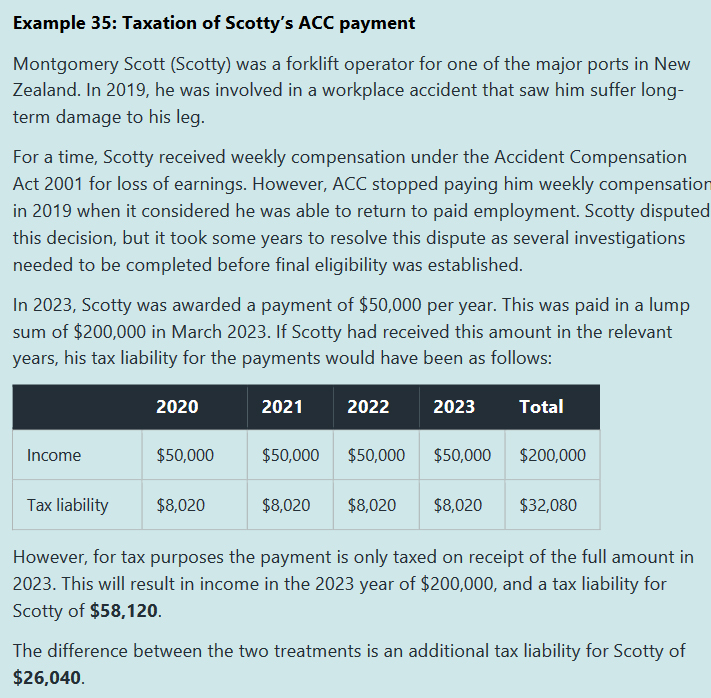

Moving on and some good news. I’ve previously covered the situation where Accident Claims Compensation Corporation has paid a backdated lump sum, representing several years compensation after the claim was initially denied before being accepted on appeal. Now, as I was explained in the past, such payments often result in over taxation relative to the tax that would have been payable if the payments had been made at the correct time. The commentary gives an example of this where the claimant would have an additional tax liability of $26,040 as a result.

The Bill proposes to change this by allowing a tax rate to be used when a backdated lump sum payment is paid to be based on the recipient’s average tax rate for the four years prior to the tax year in which they receive the backdated lump sum payment.

There will also be provisions relating to lump sum payments made paid by the Ministry of Social Developments and those will eliminate any potential further tax liability for recipients.

According to the accompanying regulatory impact statement, the effect of this over taxation is roughly about $9 million a year. This is great news, and one I’m personally pleased about because I’ve been lobbying in the background for Inland Revenue for some time to make this change.

These new rules will take effect from 1st April 2024. Personally, I’d like to see them in effect, from 1st April this year, and I’ll submit on that. But don’t hold your breath on that one.

There’s a number of other measures in the bill, including a proposal for the Government to pay a 3% KiwiSaver contribution on the amount of paid parental leave received by a KiwiSaver member. The this will be made providing the recipient also pays the 3% employee contribution. The idea is to help increase the KiwiSaver balances of paid parental leave recipients, many of whom are women and whose ability to save has been disrupted because they take time out of the workforce to raise children. This is a welcome measure.

As usual there’s a whole heap of technical amendments as well. Submissions on the Bill are now open and the closing date is 30th of June.

A taxation principles bill – putting the politics into tax?

Now, the other bill, which was a big surprise, was the Taxation Principles Reporting Bill. This bill is intended to “increase the public’s understanding of the tax system and promote informed debate and discussion about its future”. The Bill does this by proposing a set of generally accepted tax principles and then requires the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to report on how the tax system is tracking against those principles.

The idea is that “regular reporting will help the public better understand how our tax system is performing and over time, informed public consultation process on tax policy proposals.” The hope is tax policy is developed in line with “values which society considers desirable in a tax system.”

The tax principles set out in the bill such as horizontal and vertical equity efficiency, revenue, integrity, certainty and predictability, flexibility and adaptability and compliance and administration costs, are all well accepted principles, and they’ve been used in various tax reviews, both here and abroad.

There’s a framework by which Inland Revenue will be reporting annually then every three years it will provide a more thorough review. And the implication would appear to be that the Inland Revenue would be expected to be doing regular surveys of the type that just was carried out on the high wealth individuals. That at least is one interpretation of these reviews.

The Bill will take effect from 1st July this year, which means that there’s going to be little time for consultation. In fact, the closing date submissions will be 9th June, just two weeks ahead. This is an incredibly political bill – is it a harbinger of a wealth tax, capital gains tax, whatever? We shall see. It will be interesting to see how this plays out and of course, its future will be very dependent on the Election.

In the meantime, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.