18 Dec, 2018 | Tax News

Capital gains tax is the New Zealand equivalent of the Irish Border in Brexit: An intractable issue which politicians have kicked endlessly down the road without resolution. Until now. Perhaps.

The Tax Working Group’s interim report released in September follows this pattern of deferring the dreaded day.

Rather than make an outright recommendation, the interim report instead explains the policy reasons for increasing the taxation of capital and wealth before reviewing two main alternatives; broadening the taxation of realised capital gains from classes of assets not already taxed (the CGT approach), or taxing on a deemed return basis, the risk-free rate of return method.

What the TWG isn’t proposing is a separate capital gains tax regime encompassing the taxation of all gains and replacing the present rather ad-hoc approach. This is an important point which seems to have been drowned out by all the noise around the issue. The TWG is recommending a “targeted” approach to tax asset classes which are not currently fully taxed. Existing regimes such as those for financial arrangements and foreign investment funds (FIF) will remain.

This is an extension of the incremental approach to taxing capital gains which has been in place for the past 50 years. What makes the TWG’s suggestions radical is that it should effectively result in comprehensive taxation of almost all capital gains. The suggested approach should also be legislatively easier to introduce as it would not require a complete rewrite of the existing legislation.

The TWG has decided to follow the example of Canada and South Africa and adopt a “valuation-day” basis under which all the gains from the date of introduction will be taxed. The TWG rejected the Australian approach of exempting assets acquired prior to introduction of CGT as encouraging “lock-in” or the retention of assets in order to defer realising a tax liability.

A valuation-day basis does require obtaining market valuations of assets held on the date of introduction. Much has been made of the compliance costs involved in obtaining market valuations of assets with the view that these costs would be a deal-breaker.

Although such an approach would indeed be prohibitively costly, other jurisdictions which introduced valuation day CGTs have managed to resolve the compliance issue. The TWG noted the Canadian approach where the taxpayer’s cost in an asset acquired prior to the introduction of CGT could be the median of either actual cost, the value on valuation day or the sale price.

Another option would be to allow taxpayers to pro-rate the gain or loss on a time basis. This was one method allowed by South Africa after it introduced its valuation day basis CGT on 1 October 2001.

In short, adopting a pragmatic approach can resolve the valuation issue without imposing unreasonable compliance costs. (It might also require banging a few heads at Inland Revenue which too often circumscribes promising initiatives such as the Accounting Income Method with overstated fears of potential tax avoidance).

Other key features of the TWG’s proposals are that the net gains will be taxed at a person’s marginal income tax rate, no concession will be made for inflation and capital losses will generally be able to be offset against other income. In some circumstances, such as death, the gain could be “rolled-over” and only taxed on ultimate disposal. All up the proposals are estimated to potentially raise close to an additional $6 billion of tax over the first ten years.

But fitting a CGT into the existing patchwork has its issues. The “tax, tax, exempt” (TTE) approach applicable to investment vehicles such as KiwiSaver funds and other portfolio investment entities (PIEs) creates issues around aligning their tax treatment with that of individuals. This was an issue seized on by the New Zealand stock exchange (NZX) and the Securities Industry Association (SIA) in their submission to the TWG.

An answer to the problem identified by the NZX and SIA might be to tax Australasian shares using the FIF regime fair dividend rate (FDR) methodology. In this regard the TWG noted that the current 5% FDR rate was set in 2007 and may now be too high. It is considering whether that should change and whether the present comparative value option available for individuals and trusts should be removed. Alternatively, overseas shares currently subject to FDR could instead be subject to CGT, a move which would raise an estimated $680 million over ten years.

The alternative to a CGT, the risk-free rate of return method (RFRM), was proposed by the McLeod Tax Review in 2001 and adopted for the FIF regime introduced in April 2007. Its attraction is more predictable cash flows for the government and the issue of “lock-in” doesn’t arise. However, it also has issues around valuing assets, taxpayers may not have the cash flow to meet tax liabilities (an existing problem with the FIF regime), and how would it tie in with the availability of interest deductions. Intriguingly, RFRM is seen by some as a better tax solution for addressing housing inequality.

On housing, the TWG’s terms of reference exclude taxing the family home but the interim report raises the issue of whether an exception should be made for “very expensive homes” defined as worth more than $5 million. The suggestion is that imposing an upper limit should act as a deterrent to owner-occupiers over-investing in their property. It will be interesting to see if that suggestion makes it into the final report.

A largely unremarked feature of the TWG’s work is the greater attention given to the implications of the tax system for Māori. This is in marked contrast to previous tax working groups. Māori submitters were overwhelmingly opposed to a land tax, so a policy backed by the last tax working group in 2010 has this time been rejected.

Māori concerns about how a land tax would operate would be equally applicable to the RFRM alternative.

The TWG’s interim report also identified the potential implications of a CGT on Māori freehold land and assets held by post settlement governance entities as requiring further analysis. If a CGT is introduced then a possible exemption for such assets might be one outcome.

The issues the TWG identified for expanding the scope of capital taxation centre on the longer-term sustainability of the tax system in the face of growing fiscal pressures from an ageing population and the fairness and integrity of the tax system. As the interim report notes;

“Taxing capital income that is currently untaxed is likely to provide a significant and growing revenue base for the future. Such gains are the single largest source of income that other countries tax and that New Zealand largely does not. …

The lack of a general tax on realised capital gains is likely to be one of the biggest reasons for horizontal inequities in the tax system. People with the same amount of income are being taxed at different rates depending on the source of the income.”

Against this background my belief is that despite the reservations of several of its members, the TWG’s final report will recommend the introduction of a realisation-based CGT.

However, it may also suggest that its implementation is deferred by a year until 1 April 2022 to allow time for further consultation. We will be hearing a lot more speculation about CGT for a while yet.

This is my last column for 2018, my thanks to David and Gareth for their support and to all my readers and commenters, thank you for your engagement. Have a great Christmas and see you in 2019.

20 Nov, 2018 | Tax News

Terry Baucher details how the previous National-led government appears to have successfully raised at least $1 billion of extra revenue annually with little or no fanfare.

Louis XIV’s finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, famously declared that “the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest possible amount of feathers with the smallest possible amount of hissing.”

What was true in the seventeenth century remains true today. And although Colbert might not recognise much of the modern economy and tax system, he would probably still appreciate some of the sleight of hand used by New Zealand finance ministers to raise funds without too much hissing. At a rough guess the last National government seems to have successfully plucked at least $1 billion of extra revenue annually with little or no fanfare. How?

We’re not talking about specific tax related measures often of a quite technical nature. These are a staple of every government’s budget.

A long-standing option used by governments of both hues is inflation, and in particular ‘fiscal drag’. This is when income tax rate thresholds are not inflation adjusted so wage growth lifts more earners on to higher marginal tax rates.

Income tax rates and thresholds were last adjusted in October 2010. At that time someone on the average wage had a marginal tax rate of 17.5%. According to the labour market statistics for the September 2018 quarter, average weekly earnings are $1,212.82 or $63,067 annually, well above the $48,000 threshold at which the 30% tax rate applies. Even median weekly earnings at $997 are also well above the $48,000 threshold.

So how much revenue does fiscal drag raise annually? The short answer would be “Heaps.” The Budget Economic and Fiscal Update released in May’s Budget estimated the effect of fiscal drag as $1.6 billion over the five years to 30 June 2022.

A more detailed analysis of the issue was prepared for then Finance Minister Bill English in November 2016.

The aide-memoire noted that adjusting for inflation since October 2010, effective 1 April 2017, would cost $1 billion in the first year. Clearly, baulking at this “large cost,” the paper instead modelled adjustments to thresholds based on price inflation over a single year, from June 2017 to June 2018, and applying that inflation factor to current thresholds beginning 1 April 2017. This produced a cost of $220 million for the 2017-18 year rising to $720 million by 2019-20.

The paper concluded by noting “a downside to not annually indexing is that there is less transparency for taxpayers.” This is something that politicians of both hues will rather conveniently rely on when trumpeting “tax cuts.”

Although fiscal drag is a well known tactic, Bill English also employed variations of it elsewhere to raise revenue. In the 2011 Budget inflation adjustments to the student loan repayment threshold of $19,084 were frozen until 1 April 2015. This and other changes to the student loan scheme added up to $447 million in “savings” over five years. The freeze on the student loan threshold was later extended until 1 April 2017.

The 2012 Budget froze the parental income threshold for student allowances until 31 March 2016, a measure worth $12.7 million over four years. More controversially, the same Budget increased the repayment rate applying to income above the student loan repayment threshold from 10% to 12% – a defacto tax increase. This increase raised (sorry “saved”) $184.2 million in operating costs over four years.

The 2011 Budget saw changes which also stopped inflation adjustments of the threshold at which abatement of working for families tax credits applied. Instead, measures reducing the threshold over a four year period from $36,827 to $35,000 were introduced. A “slightly higher” abatement rate of 25 cents in the dollar instead of 20 cents in the dollar was also phased in over the same period. These measures were intended to realise savings of $448 million over four years. (The current government’s Families Package partly reversed these changes by raising the abatement threshold to $42,000 whilst lifting the abatement rate to 25 cents in the dollar from 1 July 2018).

The 2011 Budget also removed the exemption from employer superannuation contribution tax (ESCT) on employer contributions to KiwiSaver funds. This is probably the biggest single measure that increased the tax take outside of the rise in the rate of GST to 15% in October 2010.

The exemption was removed with effect from 1 April 2012 and the compulsory employer contribution was also increased from two to three percent from 1 April 2013. These changes saw the annual ESCT collected rise by almost $400 million from $681 million in the June 2011 year (the last full year before the changes) to $1,078 million in the June 2014 year (the first full year of the changes).

Finally, there is the opportunity to increase various duties such as those on alcohol, petroleum and tobacco. For example, tobacco excise duty has been increased every year since January 2009 as part of the country’s Smokefree policy. As a result, the excise duty per cigarette has gone from 30.955 cents per cigarette in 2009 to 82.658 cents per cigarette as of 1 January 2018. During the year to June 2018 the government collected over $1.8 billion in tobacco excise duty.

All told, the combination of fiscal drag, ESCT increases and changes to student loans and working for families cumulatively represent at least $1 billion of additional revenue collected annually. Throw in the various excise duty increases, specific “base protection” tax measures such as changes to the thin capitalisation rules for foreign-owned banks or the the “Bright-line test” introduced in 2015, and the increased annual “tax” take is close to $1.5 billion.

These under the counter tax increases have happened with little fanfare under the guise of “savings”, or “better targeting of government programmes” (how the Budget 2011 changes were described). Colbert would no doubt approve of this efficient plucking of the goose with very little hissing.

9 Nov, 2018 | Tax News

Terry Baucher wades through a series recent IRD reports and concludes the taxman has room to improve

Whatever the final recommendations of the Tax Working Group are, Inland Revenue will be a key player in implementing and managing the changes to the tax system. But is it up to the task?

In the run-up to Labour Day weekend it released its 2017-18 annual report and two other reports. Collectively, these reports give a good insight into its current and future state which might be summarised as “Can do better.”

The first report released was the result of some follow up research on “strengthening stakeholder engagement.”

Undertaken by Wellington based research firm Litmus, the research targeted groups identified by Inland Revenue as having an important role in its billion-dollar Business Transformation process. The stakeholders surveyed included central and local government agencies, business representative groups, large enterprises, vendors and suppliers and tax agents/intermediaries.

Litmus surveyed 229 organisations and received 118 responses. Just seven of the mere 10 tax agents surveyed responded. Given there are 5,600 tax agents with over 2.7 million clients, tax agents represent a substantially under-represented demographic in the final survey’s results.

Significantly, the feedback from tax agents was less positive than from other stakeholders. According to the report, tax agents were “less supportive about how Inland Revenue is changing and its ability to deliver”, with only a third “confident Inland Revenue will successfully deliver the change.”

It might be tempting for Inland Revenue to argue the small sample size means the Litmus survey was not representative of tax agents. However, its customer satisfaction surveys show that those tax agents surveyed who were “very satisfied” with Inland Revenue declined from 77% in 2015-16 to 66% in 2017-18. This was the largest drop amongst any of the surveyed groups.

An explanation for the dissatisfaction of tax agents can be found in Inland Revenue’s 2017-18 annual report.

The upgrade of Inland Revenue’s secure online service myIR in April 2018 (“Release 2”) did not go smoothly. Users had problems logging on and some services became unavailable. Frustrated taxpayers and tax agents rang Inland Revenue for assistance only to find their call “capped” by Inland Revenue because call volume exceeded its capacity. As page 38 of the annual report explained:

“We capped 286,392 calls during June 2018 to manage the spike in demand. This is a 69% increase from 169,533 capped calls in June 2017. This contributed to an 85% increase in complaints in April-June 2018 compared to the same three months in 2017. We received 3,541 customer complaints during this quarter, 1,623 of which were received in June 2018.”

Inland Revenue eventually resolved the problems encountered in Release 2, but it faces a much bigger test with Release 3 next April which will affect over a million taxpayers.

Its annual report has some fascinating details about how Inland Revenue is progressing with its Business Transformation programme. Its use of contractors and temporary staff has almost tripled in the past three years: increasing from $45.3 million in the June 2015 year to $124.1 million in the June 2018 year. Spending on contractors and temporary staff represented 22.8% of all Inland Revenue’s $545 million personnel costs for the June 2018 year.

The increase in the use of contractors and temporary staff is almost certainly down to implementing the Business Transformation programme. 11% of Inland Revenue’s 5,250 staff are now on fixed-term contracts compared with 2% in June 2014. Despite this shift, the proportion of staff who are female has remained constant at 64% over the same period. However, the department has a gender pay gap of 19.4% as the difference in average salaries for men and women is $16,235. As the report explains “Women only make up 43% of the people who earn over $100,000, while they make up 68% of the people who earn under $100,000.”

After four years of declining recruitment Inland Revenue made 604 new hires in 2017-18. However, during the year 938 staff left which is why Inland Revenue paid out over $21 million in termination benefits, a more than twenty-fold increase from the $919,000 paid during the 2016-17 year. The staff losses meant its staff turnover for 2017-18 was 15.4% overall, not exactly an encouraging sign of a healthy workplace. Curiously though, the average length of service of staff rose to 13.6 years. (Incidentally, the department paid $339,000 in bonuses during the year although it’s not clear to whom).

And yet, despite all these comings and goings, Inland Revenue’s personnel costs for the June 2018 year were lower than budget by over $87 million. According to the report:

“The majority of this variance reflects the change in both the phasing and delivery of the Business Transformation programme, and organisational change required to deliver the programme outcomes.”

All this points to an organisation in a state of flux with an unsettled workforce, hence the recent strikes. It’s one reason why I and many other tax agents are dissatisfied with Inland Revenue’s current performance and view the approaching Release 3 next year with some concern.

Apart from collecting $73 billion of revenue during the year, Inland Revenue also did its bit for the government’s books by returning a surplus of more than $59 million to the Crown. This seems to be part of a deliberate policy – over the five years to 30 June 2018 the department recorded surpluses totalling more than $192 million.

The financial statements included in the report have some other interesting revelations: child support collections exceeded payments to caring parents by $181 million. Again, this is a long-standing policy: the corresponding amount for June 2017 was $184 million. Child support late payment penalties, which at 36% per annum in the first year are more than those payable for late payment of tax, effectively represent a backdoor tax on liable parents.

A serious review of child support debt is long overdue: despite writing off $594 million of debt during the year, the total child support debt at 30 June was $2,259 million. This is Inland Revenue’s largest single debtor type. By comparison the total of GST, PAYE and income tax outstanding at 30 June was $2,841 million. The $1,662 million of child support penalties owed is more than the $1,651 income tax outstanding, an absurd position.

Inland Revenue also collected $49.796 million of “other revenue” during the year. Unexplained in Inland Revenue’s annual report, it transpires that this is the total of penalties imposed in relation to late repayment of overpayments of working for families’ credits. I found the answer in note 3 to the government’s financial statements for June 2018, which includes $231 million of “Child support and working for families penalties” in its Sovereign Revenue for the year.

To put that total in context, it’s almost double the $118 million of court fines included as revenue in the government’s financial statements. Penalties on top of repaying overpaid working for families credits seems a harsh outcome for what is most likely to be the result of an error.

The annual report also details the vast amount of data sharing going on between Inland Revenue and other government agencies. During the year the department received 520,561 “contact records” from the Department of Internal Affairs. The Ministry of Social Development (MSD) provided details to Inland Revenue during the year relating to 94,378 child support cases. MSD also shared 7,041,500 student loan cases in what must have been a one-off information transfer. Inland Revenue in return shared details with MSD relating to 1,373,489 Community Service Card holders, 402,047 child support cases as well as proactive information sharing for 743,346 benefits and student cases.

Quite apart from data sharing with other government agencies, during the year Inland Revenue sent details of 128,930 persons to the Australian Tax Office as part of its Student Loan collection programme. This resulted in matches being found for 85,147 persons who will soon find they have not escaped their student loan repayment obligations.

The extent of data sharing currently going on between Inland Revenue and other agencies here and around the world is enormous yet goes largely unnoticed. It invariably comes as an unpleasant surprise to anyone caught up by the data exchanges. A data leak would surely represent one of the biggest risks for the department, but it’s not clear from the annual report whether the independent Risk and Assurance Committee has specifically considered the issue.

The other document released, Statement of Intent 2018-2022 (the SOI) is rather like a glossy corporate brochure packed full of buzz-words and corporate-speak. The SOI never uses the word “taxpayer/taxpayers”, instead “customer/customers” appears 141 times in the 24-page document. This aversion to using the word “taxpayer” is also apparent in Inland Revenue’s Annual Report: it appears a mere 41 times in 224-pages compared with 708 mentions of “customer/customers” – more than 17 times more frequently.

The use of “customer” is well meant, but in my view is ultimately disingenuous. It implies a voluntary relationship which simply does not apply to an organisation extracting money with the full power and backing of the state. As anyone involved in a dispute with Inland Revenue will attest, its view is not “the customer is always right,” but “the taxpayer is guilty until proven innocent.” The alternatives to Inland Revenue are not a “competitor” tax agency, but either outright non-compliance or emigration. Inland Revenue would do better to more honestly recognise that for most people it is the “Bad Guy” and use its new “customer-centric” approach to ameliorate that reality.

In fairness, for all its earnest corporate-speak, the SOI recognises that Inland Revenue’s future success is dependent on trust. Page 11 of the SOI comments:

“[Trust] is vital for motivating people to pay their taxes and for the successful implementation of policy. This trust has been eroding in many countries. The situation is not yet clear in New Zealand, but longer term it may mean Inland Revenue cannot rely on operating in an environment of high trust. There are already differing levels of trust in Inland Revenue and the wider public sector between different ethnic, socio-economic, and demographic groups.”

Currently Inland Revenue will need to work hard to maintain trust in it, particularly amongst tax agents. The next stage of the Business Transformation programme (Release 3) in April 2019 is therefore both a threat to that trust yet also an excellent opportunity to reinforce the public’s trust in it. Inland Revenue is at present outwardly confident that Release 3 will succeed. We’ll have the first verdicts on whether that confidence was justified in under six months’ time. Watch this space.

24 Sep, 2018 | Tax News

Although intertwined with the issue of capital gains, finding a fairer treatment for retirement savings is arguably the most important objective for the TWG, says Terry Baucher

Rather like Dug in Up almost all the commentary around the Tax Working Group’s (TWG) interim reporthas chased the squirrel of capital gains tax (CGT).

Although probably inevitable, the focus on CGT risks overlooking some of the other issues analysed in what is probably the most comprehensive overview of New Zealand’s tax system in nearly thirty years. These other issues would include land tax, GST and retirement savings.

Although a final decision on the optimum approach to taxing capital gains will wait until the TWG’s final report next February, the Government has accepted that the TWG need not carry out further analysis of areas such as wealth tax, land tax, changes to New Zealand’s petroleum and minerals royalty regimes, GST coverage and a financial transactions tax.

I am very surprised that a land tax is completely off the table, particularly after the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group came out strongly in favour of it in 2010. Reading between the lines, the TWG appears to have decided the politics of a land tax are even more difficult than those around a CGT. Conversely, given the general tenor of the TWG’s comments on the issue of taxing capital, removing the land tax option probably increases the likelihood of either a CGT or taxing capital based on a risk-free rate of return being recommended.

No change for GST

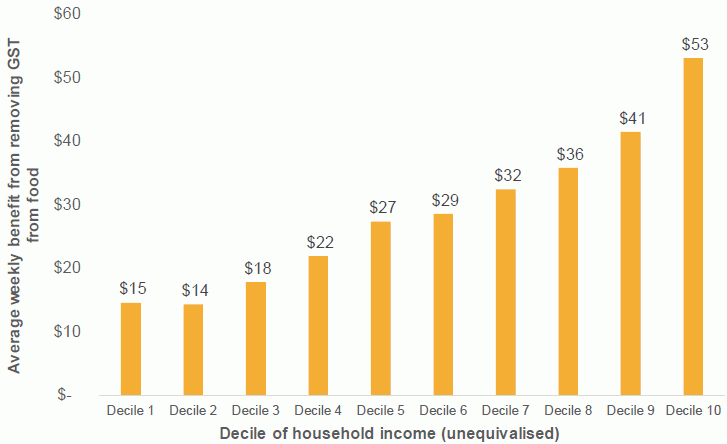

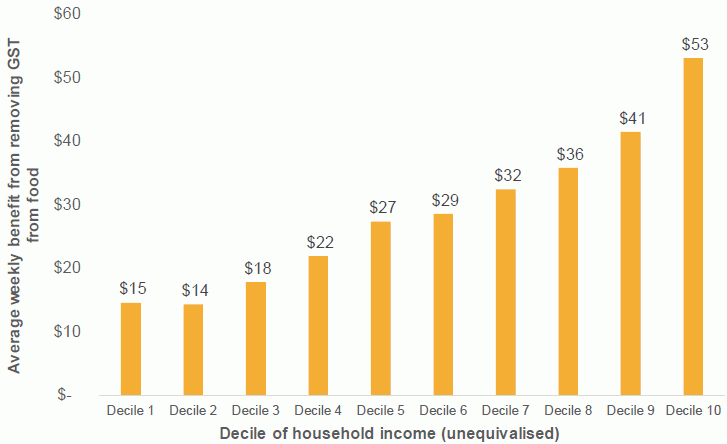

On the other hand it is no surprise that the TWG isn’t recommending changes to the current GST framework. The arguments for exempting food from GST are pretty comprehensively demolished by the following graph illustrating the average weekly benefit for each income decile resulting from removing GST from food:

In order to achieve this benefit, the TWG estimates an exception for food and drink would reduce the GST take by $2.6 billion. As the group notes, if that amount was instead redistributed, each household would receive $28.85 per week, or practically double the benefit of a GST exemption for the lowest two deciles. As the TWG concluded other measures than an exemption, such as welfare transfers, would be likely to produce greater benefits for the same cost.

This point is also borne out when considering an alternative measure, an across the board cut in GST from 15% to 13.5% costing $2 billion annually. The result was indentical to that for introducing a GST exception; there were significantly greater benefits to households in the highest income decile.

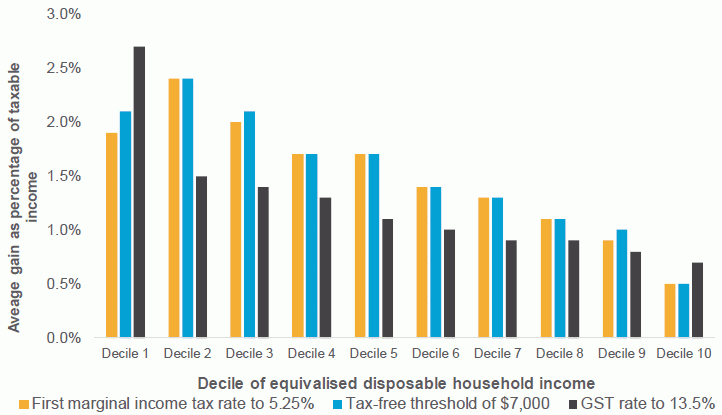

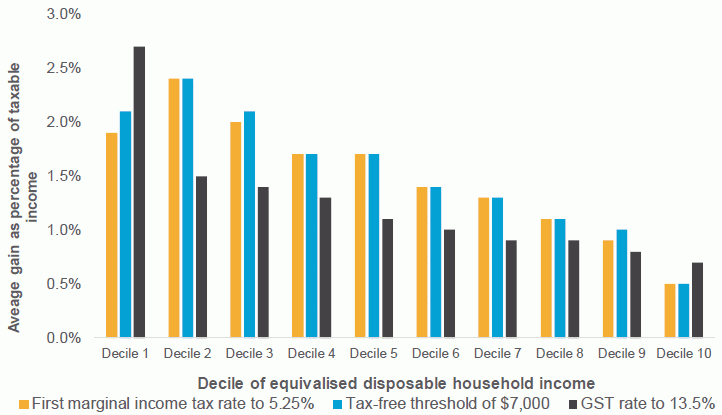

The TWG then compared a GST rate reduction with two alternative measures: a tax-free threshold of $7,000 and halving the lowest tax rate from 10.5% to 5.25%.

The conclusion was that based on percentage of income, reducing the GST rate to 13.5% would provide greater benefits to households in the lowest income decile when compared with the suggested income tax changes. However, there were fewer benefits for households in deciles 2-9 and households in the highest income decile would be the biggest winners.

The TWG therefore decided against recommending a reduction in GST rates, suggesting instead:

“If the Government wishes to improve incomes for very low-income households, the best means of doing so will be through welfare transfers.

If the Government wishes to improve incomes for certain groups of low to middle income earners, such as full-time workers on the minimum wage, then changes to make personal income taxes more progressive may be a better option.”

As part of its review the TWG looked at whether financial services such as bank fees should be brought within GST and eventually determined “there are no obviously feasible options for doing so.” Instead, the TWG proposes the Government should monitor international developments.

The TWG also dealt briskly with the idea of a financial transactions tax (or Tobin tax) on tax on the purchase, sale, or transfer of financial instruments. This was proposed by ‘many submitters’ on the basis of improving market stability and discouraging speculative trading. The TWG concluded:

“The revenue potential of a financial transactions tax in New Zealand is likely to be limited, due to the ease with which the tax could be avoided by relocating activity to Australian financial markets…A financial transactions tax is an inefficient tax that is unlikely to raise significant revenue for New Zealand.”

The door isn’t completely shut on a financial transactions tax, with the TWG recommending the ongoing international debate on the issue be monitored.

Changes ahead for KiwiSavers?

In many ways it’s appropriate Sir Michael Cullen is chair of the TWG as his imprint lies directly and indirectly across the current treatment of retirement saving. Sir Michael was part of the Fourth Labour Government’s radical overhaul of savings in the late 1980s which adopted the present Taxed – Taxed – Exempt’ (TTE) basis for retirement savings. In 2007 as Finance Minister in the Fifth Labour Government he introduced KiwiSaver and the Portfolio Investment Entity (PIE) tax regime. Both, were, more than a little ironically, measures aimed at redressing some of the issues which emerged in the wake of the adoption of the TTE regime.

The report’s review of KiwiSaver begins with an interesting analysis of the impact of inflation on taxation. The report observes:

“Although inflation is currently low, nominal interest rates are also low; this has made inflation a larger component of the nominal interest rate and therefore increased the real effective tax rate on debt.”

The effect of inflation is illustrated in the following table:

| Table 7.2: The future value of $1,000 invested today after 30 years |

|

No tax |

Tax real income |

Tax nominal income |

| 17.5% |

28% |

17.5% |

28% |

| Future value of $1000 in 30 years |

$4,322 |

$3,719 |

$3,396 |

$3,362 |

$2,889 |

| Effective tax rate on nominal income |

N/A |

10.5% |

16.8% |

17.5% |

28% |

Effective tax rate on real income

(after taking account of inflation) |

N/A |

17.5% |

28% |

29.2% |

46.7% |

The report concludes that the member tax credit offsets the impact of taxing nominal income for KiwiSaver members earning up to approximately $100,000 per annum. Above that level of income the member tax credit’s effectiveness diminishes.

As the TWG report notes the TTE basis of taxation was, and remains, a significant divergence from the ‘Exempt – Exempt – Taxed’ (EET) basis common in many OECD countries. However, reverting to EET would be a very expensive move: the report estimates the annual fiscal cost of doing so would be at least $2.5 billion initially.

Even with strict limits on contributions most of the tax benefits of moving to an EET system would flow through to high-income earners. The TWG, rightly in my view, considers there is “little value in providing incentives to high income-earners, who are likely to be saving adequately in any case.” (Part of the reason for high income-earners being better savers is that they are more likely to be property owners).

This background of inflation and the potentially expensive and regressive risks of saving concessions led the TWG to:

“Focus on options that are targeted towards low- and middle-income earners – which, in turn, will disproportionately benefit women (who are more likely than men to be on lower incomes, due to part-time work or time out of the paid workforce for caring responsibilities).”

The TWG’s two main proposals are therefore:

- Remove the Employer Superannuation Contribution Tax (ESCT) on the employer’s matching contribution of 3% of salary to KiwiSaver for members earning up to $48,000 per year; and

- Reduce the lower PIE rates for KiwiSaver funds by five percentage points each.

The ESCT proposal would reverse the change introduced in the 2011 Budget and revert the treatment of employer contributions back to what it was when KiwiSaver was established at an estimated annual cost of $180 million. The reduction in PIE rates for KiwiSaver funds would cost a modest $35 million annually.

The TWG also considered the implications for KiwiSaver funds of taxing gains on New Zealand and Australian shares, a matter raised by National MP Paul Goldsmith in Parliament last week. The measure would impose tax of approximately $15 million per annum for those KiwiSaver members with income below $48,000, far outweighed by the proposed changes.

However, the change would cost approximately $45 million per annum for higher income KiwiSaver members. As a counter to this, the TWG suggests the member tax credit could be increased from its present 50 cents per dollar to 60 cents per dollar at an annual cost of $190 million.

Although intertwined with the issue of capital gains, finding a fairer treatment of retirement savings is arguably the most important objective for the TWG. This is because there are now almost 2.9 million KiwiSaver members, 1.3 million (46%) of whom are under the age of 35.

The sums involved with KiwiSaver are large and growing: in the twelve months to August 2018 employer and employee contributions exceeded $5.4 billion with Member Tax Credits contributing a further $785 million. Employees and employers contributed a record $612 million in August 2018 alone.

The TWG proposals for retirement savings therefore will have a significant impact for a large and growing number of New Zealanders long into the future. The interim TWG proposals are modest but do represent a positive step forward. More than just property owners will be watching and awaiting the TWG’s final recommendations.

14 Sep, 2018 | Tax News

Terry Baucher hopes to see the Tax Working Group signal a break from the past, either in the form of a Capital Gains Tax or something else such as a land tax

Does the news that the Tax Working Group’s interim report due very shortly won’t specifically recommend a capital gains tax (CGT) mean it will be the fifth such group in the past 50 years to have considered the issue before concluding “Yeah, nah”?

Not yet. Firstly, this is an interim report which is intended to invite further commentary on the TWG’s initial proposals. This is broadly similar to the process followed by the McLeod Tax Review in 2001. My understanding is that the interim report will analyse in some detail not only the merits or otherwise of a CGT but also how it might work in practice. It will probably be the most comprehensive review of the issues around CGT since the Consultative Document on the Taxation of Income from Capital in 1990.

Although the issue of CGT is dominating attention, the TWG has a very wide brief and its interim report will examine other issues such as the overall design and fairness of the tax system, environmental taxes, the taxation of savings, GST exemptions for particular goods, the taxation of companies and multinationals, the possibility of a land tax and taxpayer rights in dealing with Inland Revenue. The resulting report will be substantial and is probably likely to run to over 200 pages. Yet, for all that the focus will be on the TWG’s proposals around the taxation of capital.

Rather like Banquo’s Ghost the issue of CGT has been an unwelcome guest for every tax review over the past fifty years. During that time the debate over CGT has developed a Groundhog Day quality to it. Every few years a review of New Zealand’s tax system is announced. Some months later, after due deliberation, a report is released which includes passages summarising the pros and cons of a CGT before concluding, somewhat reluctantly, it is not appropriate.

In between each review a major change is introduced widening the scope of income tax to include transactions previously treated as exempt capital gains. These legislative changes essentially undermine the previous review’s reasoning against a CGT. At frequent intervals, international organisations such as the OECD and the IMF will call for a CGT to address imbalances in New Zealand’s economy around housing and saving. The IMF’s recommendation in March 2017 for a CGT was just the latest such instance.

Meantime, as if thumbing their noses at each tax review’s arguments against a CGT, the list of countriesintroducing capital gains tax legislation grows: Canada in 1972, Australia in 1985 and South Africa in 2001.

This rather pusillanimous pattern began with the Ross Committee in 1967 which after declaring “On grounds of equity there is strong justification for taxing realised capital gains,” concluded “we have finally decided against such a recommendation”. The Ross Committee was followed in 1982 by the McCaw Task Force, which opined “The Task Force considers that failure to tax real capital gains is inequitable in principle, and is seen by many to be so.” Ultimately, the McCaw Task Force was “not convinced of the need for a separate capital gains tax, does not propose its introduction, even though capital gains are being made by some which should in principle be taxed.”

The McLeod Tax Review in 2001 detemined “New Zealand should not adopt a general realisation-based capital gains tax. We believe that such a tax would not necessarily make our tax system fairer and more efficient.” It then proceeded to hedge its bets by adding; “Nevertheless, we also remain of the view that the absence of a tax on capital gains does create tensions and problems in specific areas.”

In 2010 it was the turn of the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group. In time-honoured fashion its report concluded:

“The most comprehensive option for base-broadening with respect to the taxation of capital is to introduce a comprehensive capital gains tax (CGT). While some view this as a viable option for base-broadening, most members of the TWG have significant concerns over the practical challenges arising from a comprehensive CGT and the potential distortions and other efficiency implications that may arise from a partial CGT.”

And yet, despite all this previous consideration and rejection, another tax review finds itself confronting the CGT issue anew. There are several key factors as to why this pattern endures but three merit closer review.

Firstly, in the absence of a comprehensive CGT, there is presently no clear legislative framework to deal with the taxation of capital gains in general and the arrival of completely new asset classes such as cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. This results in confusing uncertainty as some taxpayers report gains as income whilst others treat the gains as tax free. Although issues still arise in other jurisdictions with capital gains regimes, investors know that returns will be taxed either as income or under the relevant CGT regime.

By contrast investors in cryptocurrencies are presently unsure about whether gains are taxable or exempt. This all-or-nothing approach understandably tempts investors to treat gains as tax free sometimes on the most dubious of grounds. Even though the bright-line test relating to sales of residential property has been law now for almost three years, there appears to be widespread non-compliance.

Secondly, as every tax review has acknowledged to varying degrees, the present tax treatment of capital is inequitable and creates unfairness. Differing tax treatment applies to different classes of assets leading to what the 2010 review called ‘incoherence’. The TWG’s brief includes reviewing the overall fairness of the system and in this regard the background issues paper noted that “real property held for more than two years (soon to be five) is undertaxed relative to other investments when there are capital gains”. Since peaking at 73.8 % in 1991 home ownership has fallen steadily to 63.2% in 2016. This means those substantial untaxed capital gains are being derived by fewer people.

Separate from the issue about unfair tax treatment the TWG is also considering the issue of wealth inequality. A background paper on the taxation of capital Income and wealth commented:

“Something that may not have been given enough attention in the discussion until recently has been that wealth ownership has a very skewed distribution, and reducing the tax on capital income may have contributed an increasing level of inequality in many developed countries in recent years.”

This combination of growing wealth inequality and favoured tax treatment for some assets, most notably property, means that the issue of a CGT is unlilkely to fade away even if the TWG decides not to recommend it. At some point the nettle must be grasped either through a comprehensive CGT or some other tax such as a land tax.

Finally there is plain simple self-interest. Not just of groups such as the NZ Property Investors Federation but of our elected representatives. As Thomas Coughlan pointed out earlier this week currently 113 MPs own 306 properties between them or an average of 2.6 each. At a time of falling home ownership only seven MPs do not own any property meaning property owners are greatly over-represented in Parliament. Even if the TWG does recommend a CGT, getting it into law will require a large number of MPs to decide their self-interest in getting re-elected outweighs their pecuniary self-interest.

We’ll know in a few days whether the present TWG is proposing to break the pattern of fifty years or whether we’ll find ourselves re-hashing the same arguments in 10 years time. I’m hopeful that we will see the TWG signal a change of approach, either in the form of a CGT or some other mechanism such as a land tax. For now it’s a question of wait and see.