- IMF suggest a CGT

- Crypto-asset reporting

- Auckland’s budget

The Greens announced their tax proposals a week ago, last Sunday.

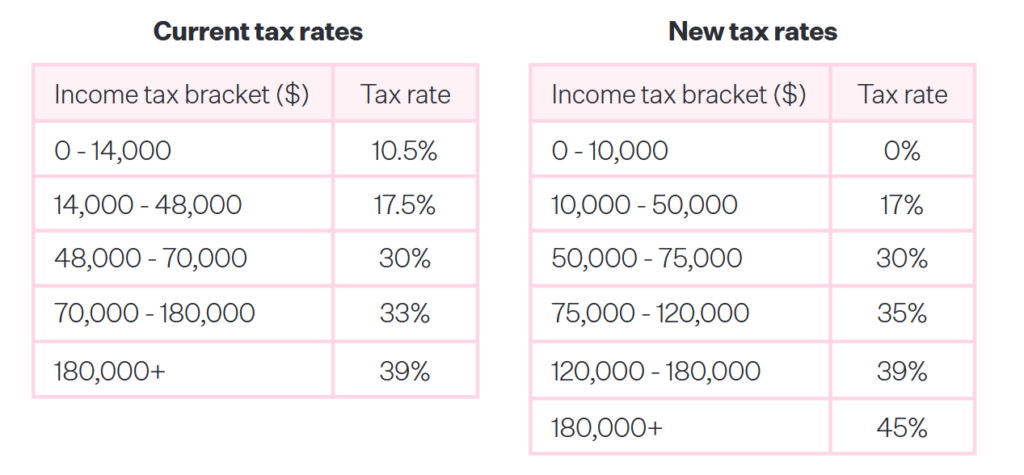

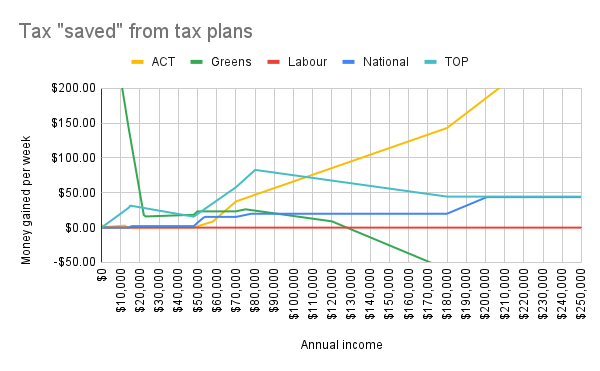

And my reaction was, “These are very bold.” They proposed major tax cuts at the lower end, meaning 95% of taxpayers will be better off under the Greens. Those cuts are paid for by increasing the top tax rate to 45% and increasing the 33% tax rate to 35% as well. These increases are part of the trade-off for the proposed nil rate band of $10,000, which no doubt will be very popular. As is well known, many other jurisdictions have something similar and given the fact that nothing has been done in relation to indexation of thresholds for well-nigh 13years now, it’s unsurprising that the pressure is built up, particularly at the lower end, to change the tax rates.

But most of that got swept away by the Greens controversial wealth tax proposal. In summary, there are two parts to it. Any individual whose net assets, net of mortgages for example, exceed $2 million will be subject to a wealth tax of 2.5% on the excess. For family trusts there is no nil rate band or threshold at all. It’s a flat 1.5% which is a deliberate anti-avoidance mechanism.

Latest Inland Revenue data on trusts

Trusts were used to avoid the impact of estate and gift duties in the past and are used in other jurisdictions to mitigate the impact of wealth and estate duties. So, the Greens have targeted this avoidance. Coincidentally, last Saturday the New Zealand Herald published a piece including details of the trust tax return filings made to Inland Revenue for the year end 31st March 2022 which indicated the value of assets held in trusts. The net assets of the 201,100 trusts which reported, was just over $300 billion. So at 1.5%, theoretically that’s $4.5 billion dollars straight up there.

Incidentally, what that Inland Revenue report doesn’t show is the non-reporting trusts, those are likely to be quite significant. We really don’t know how many trusts there are in New Zealand, the best estimates are somewhere between 500,000 and 600,000. Many of the non-reporting trusts don’t do so because they have no income, but they hold assets such as the family home. So, family homes that have been held in trusts may now be subject to the Greens’ proposal.

Now this kicked off quite a storm, which I watched with a little bemusement because the Greens first of all have to put themselves in a position of such leverage that its coalition partners, almost certainly Labour and Te Pati Māori, agree to the proposal. And then somehow between 14th October, the date of the election, and 1st April next year, the legislation to introduce all of this is drafted and passed through Parliament. So ,it’s a big challenge ahead.

But it caused quite a stir, and I fielded several calls from people concerned about what they saw here, trying to get an understanding about it and my views on it. At our Accountants and Tax Agents Institute New Zealand’s regional meeting on Tuesday we had a very lively debate around the question of this wealth tax. Normally, a lot of the time we’re talking about what’s in the legislation and whether Inland Revenue ever answer their phones again. All this I think shows the impact of the proposals, even though in theory they affect only a small group of people, the top 1%.

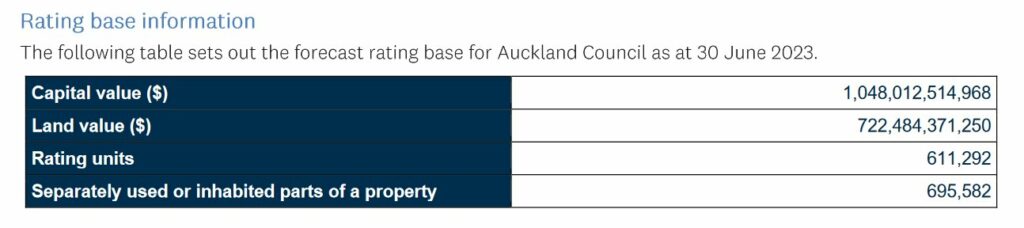

But there is substantial wealth locked up in property. We know that from digging around the official figures. For example, Auckland Council estimates the rateable value for all property within the Auckland Council region will be over one trillion dollars as of 30th June. Obviously, not all of those would be subject to a wealth tax.

What’s being suggested by other parties?

But I thought it was interesting that people are taking the Green’s proposals very seriously. The income tax shift to 45% on income over $180,000 won’t be terribly popular. But at present, the proposals that they’ve put out for the income tax cuts would affect many more people and benefit many more people, all those earning under $125,000, which is something like just over 4 million people. This has a broader impact than either National or Act’s proposals.

It’s quite interesting now as the election comes ever closer, we can start to see the tax policies of the various parties taking shape. The Greens are raising a substantial amount of tax to deal with poverty. Act is proposing tax cuts and it’s taking the ideologically opposite approach of substantial cuts to spending in order to achieve its top rate of 28%.

TOP, The Opportunities Party, are putting out a policy which has a land value tax, and they also propose tax increases at the higher end together a nil rate band and also substantial tax cuts at the lower end.

We haven’t yet heard from Labour on what they would do. Over on Twitter @binkenstein put together a graph comparing the various parties’ proposals so far.

So, the debate has ramped up quite a bit. Obviously, the Greens wealth tax is the most controversial part of it, but the other part which really got very little commentary but is equally controversial, was a proposal to raise the income tax rate for companies from 28% to 33%. More than most of the Greens’ proposals, that would probably produce a certain frisson of tension amongst multinationals. They may look and think “Maybe we might not increase our activities in New Zealand” or they may ramp up what they try and do under profit shifting.

Anyway, it all made for a very lively discussion all round. As I told people, wait and see. But it is interesting to see the pressure point for those are likely to be affected around a wealth tax.

What does the IMF think?

With almost impeccable timing, the IMF, the International Monetary Fund, were in town and it suggested that maybe it was time for a capital gains tax.

The Concluding Statement of the 2023 Article IV Mission noted:

Well-designed tax reform could allow for lower corporate and personal income tax rates by broadening the tax base to other more progressive sources, such as comprehensive capital gains and land taxes, while also addressing fiscal drag and improving efficiency.

It’s not the first time the IMF has suggested changing the tax system. They did so in 2021. In fact, there’s a regular pattern of the IMF and/or the OECD coming here looking around saying, “Well, guys, the country is in good shape, generally government policy is pretty sound, but you need to do something about capital gains taxes.” Regardless of whichever party is in power the Government’s reaction is quite funny. They like the bit about everything being under control. But at the mention of capital gains tax, they all throw up their hands in horror. And yet, as we know all around the world, capital gains taxes are a common feature of tax policy.

The Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework, the latest expansion of the Common Reporting Standards

Now, the Greens wealth tax proposal will probably be music to the ears of the French economist Thomas Piketty, who has proposed a global wealth tax, as one of the core points of his monumental work, Capital in the 21st Century. And at the time of publication in 2014, the opportunities for that global wealth tax to ever eventuate were probably just about zero or maybe marginally above zero.

But since then, we’ve had the introduction of the Common Reporting Standards which I think is actually revolutionising the tax world quietly because an enormous amount of information sharing is now happening on. We know from what’s been reported under the Automatic Exchange of Information that there’s something like €11 trillion held in offshore bank accounts. The Americans have got their FATCA, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, and as a result of that, they know that American citizens have got maybe US$4 trillion held offshore.

Now, the latest part of the Common Reporting Standards is extending the framework to crypto-assets and I talked about this last year when the proposals first came out. Those proposals have now been finalised and the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework is now in place. There have also been some amendments to the Common Reporting Standards. I’m going to cover all these changes in a separate podcast because I think they’re worth looking at in a bit more detail.

The tightening noose of information exchange

But the key trend in international taxation that’s going on, which I think is going to have a long-term impact around the world, and particularly for tax havens, is this growing interconnectedness, the sharing of information that goes on between tax authorities through mechanisms such as the Common Reporting Standards. I asked Inland Revenue about what information they had been supplied under the CRS in relation to the numbers of taxpayers and the amounts held in overseas bank accounts. Inland Revenue turned down my Official Information Act request on the basis that much of this is obviously confidential, but also would be compromising to the principles under which the information is shared.

Now, I’m not entirely sure about that. I think the more openness we have about what is being shared, the better the likelihood of tax enforcement once people cotton on to what’s happening. They will not think “Yeah, well, I’m just going to leave it over in the UK or the US or wherever, and Inland Revenue will never find out.” My view, as I tell my clients, is they always find out and they know much, much more than you can imagine.

And outside of the CRS there appears to be a regular exchange of information about property purchases between the United States Internal Revenue Service and Inland Revenue here. So be advised, the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework is just the latest in a building block of international information exchange.

The Auckland Budget – what about climate change?

And finally, the Auckland budget got signed off last week. I’ve been in the press disagreeing with the sale of any part of the Auckland airport shares, and I still stand by that. I think it’s a short-term fix for a long-term problem, but that’s now done and we move on.

What I did think was quite surprising as you delve into the budget is some of the numbers that come out. As I mentioned earlier, the rating base for Auckland and according to the Auckland Council’s documents is over $1 trillion.

But the thing that really surprises me, which wasn’t addressed in the budget so we’re going to have to address it next year, is the question of climate change. Towards the end of the process, the Government announced that in the wake of Cyclone Gabrielle 700 homes around the country are too risky to rebuild. The Government and councils will offer a buyout option to those property owners.

400 of those are in the Auckland region and apparently it doesn’t also take into account what is going to have to happen out at Muriwai because of the slips and the dangerous cliffs over there. As Deputy Mayor Desley Simpson pointed out, “If you say it’s 400 [Auckland homes] times $1.2 million, give-or-take just like the average house price, you’re talking half a billion dollars.”

The question arises how is that split between Auckland ratepayers and the rest of the country? Yet there was nothing in the Auckland budget about this, and that’s just this year’s damage. What happens if we get another Cyclone Gabrielle, next year?

We’ve got an interesting scenario developing where we’re talking about reducing emissions and we’ve got a distant horizon 2030 or whatever farmers and other parties want to extend it to. But in the meantime, we are picking up the bill now for increased damage and we don’t seem to be thinking in terms of how does that affect our taxes and rates? And this is going to be an ongoing issue. So, the question of paying for that, whether it’s a wealth tax, capital gains tax, whatever, is going to become ever more present, in my view.

That’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.