- Bright-line test red flags

- How to tax wealth

- IMF and Climate Change Commission suggest changes to the Emissions Trading Scheme are needed.

Like a never-ending Groundhog Day, every International Monetary Fund report on the New Zealand economy suggests tax reforms would promote efficiency. For example,

“There is a sense that the asset allocation in New Zealand households has a bit too much emphasis on housing versus other investments. We think a capital gains tax at the margin would help.”

That was IMF Mission Chief Thomas Helbling in 2017.

This year, the IMF Mission noted:

“…tax policy reforms are needed to promote investment and productivity and growth increase, increase the progressivity of income tax and mobilise additional revenue in response to long term fiscal challenges. To achieve these objectives, reforms should combine comprehensive capital gains tax, land value tax and changes to corporate income tax.”

And invariably the IMF’s conclusions are usually followed by a fairly dismissive response from the Minister of Finance of the day.

In 2002 it was the late Sir Michael Cullen responded to that year’s report: “The IMF’s credibility is not assisted by the fact that it tends to apply the same policy template regardless of the country’s circumstances”. This year Nicola Willis’s retort was “There are some things that are certain in life, death, taxes and the IMF recommending a capital gains tax.”

Associate Minister of Finance David Seymour also weighed in commenting. “I see the IMF again saying, oh, you need a capital gains tax. Every country has one. The only countries that don’t have one are New Zealand and Switzerland. But I say let’s be more like Switzerland.”

However, I’m not so sure that this was quite the zinger he hoped because as someone mischievously pointed out on Twitter, Switzerland has a wealth tax and a $59 per hour minimum wage in Geneva.

Deputy Prime Minister and former Treasurer Winston Peters was apparently not available for comment.

A de-facto capital gains tax – the bright-line test

Now, amidst all of the commentary about the IMF’s suggestions, one of the things that came up time and again is that in many ways, we do have a de-facto capital gains tax, except we don’t call it that. The bright-line test is an example of the approach that we’ve adopted, which has been ad hoc and responsive based on the government of the day’s policies at the time.

As you may recall the bright-line test was brought in with effect from 1st October 2015 by the National Government and it then applied to disposals within two years. In March 2018 the Labour Government introduced a five-year period and in 2021 it was increased a 10-year period. And so, a quite confusing scenario has developed as to which bright-line test applies because some of the exemptions have changed over time as well, particularly in relation to the main family home.

In one way, therefore, the reduction of the bright-line test back to two years again from 1st July is to be welcomed because it is clarifying and simplifying what has become an incredibly complicated area.

Tax Red Flags: More than just the bright-line test to be considered

The bright-line test and taxation of land has plenty of red flags when together with the excellent Shelley-ann Brinkley and Riaan Geldenhuys and moderator Tammy McLeod, I made a presentation about tax red flags on Tuesday to the Law Association. (Formerly the Auckland District Law Society). My thanks again for the invitation to present and to my excellent co-presenters, we had a very lively session talking around this.

In short when you drill into our current land taxation rules, they are very incoherent. The bright-line test is a backup test. It applies if none of the other land taxing provisions apply. And this is something that tripped up people before the bright-line test was introduced and will continue to do so even now it’s been reduced down to two years.

For many people, the particular issue to watch out for is the question of subdivision. If you own a property and undertake a subdivision within 10 years of acquisition it may still be caught under the existing rules, outside of the bright-line test. And in some cases, you may be caught by the combination of the provisions with the associated persons test which deem transactions to be taxable if at the time you acquired the land you were associated with the builder, dealer, or developer in land.

Sometimes the tax charge can be triggered way past the 10-year timetable since acquisition. That’s particularly the case in relation to a disposal of property where building improvements have been carried out. That particular provision, section CB 11 of the Income Tax Act, deems income to arise if a person disposes of land and

“within 10 years before the disposal”, the person or an associate of the person completed improvements to the land and at the time the improvements were begun, the person or an associated person carried on a business of erecting buildings. Note, the reference to “within 10 years before the disposal.” So, you may have owned that land for considerably longer than 10 years and yet still be subject to the provision.

Just a pro tip for anyone thinking ‘Great, with a two year bright-line test coming in, I can now sign a sale and purchase agreement, make sure settlement takes place after July 1st and it’s not going to be subject to the bright-line test.’ That’s not the case. The sale point for the bright-line test in that case is when the sale and purchase agreement is signed and not when settlement happens. I had at least one client get caught by that very provision because they went for a long settlement thinking that got past the two year period. It didn’t, and it is another case of always seek advice on transactions involving land, because as I’ve just outlined, the provisions are complicated.

Could a capital gains tax be ‘simpler?’

And this was the point we reinforced during our seminar. There is a lot of complexity already in our tax system around the taxation of land and in my view, in some ways a capital gains tax would actually clear away a lot of that uncertainty. It’ll become clearer that, broadly speaking, if you buy something, and you sell it subsequently, any gain will be taxable.

Now, how the gain is calculated and the rate at which it’s taxed are two different things. But often in the debate around the capital gains tax, those two things get conflated to run as an argument against the taxation of capital gains.

In my view, the point still remains that we have a confusing hotchpotch approach to taxing capital gains and at some point, grasping the nettle with a CGT as suggested by the IMF and also the OECD, would ultimately perhaps be a better approach.

Incidentally, doing so would be consistent with the well-established principle we have of the broad-based low-rate approach. There’s nothing to say that by broadening the tax base, we could not hold tax rates at current levels or even lower. Bear in mind that the when the last tax working group recommended the capital gains tax, it was intended to keep to help keep the top tax rate at 33%.

Watch out for trustees on the move across to Australia

One of the other issues that came up in our Tax Red Flag Seminar was the question of trustees, and beneficiaries and settlors moving cross-border, particularly to and from Australia. That is something all three of us are seeing quite a bit of and it is something to watch out for as a key red flag.

The IMF on how to tax wealth

If there is a certain repetitiveness to the IMF’s discourse about taxing capital, it’s part of a global discourse on the topic. Earlier this month the IMF released a How to Tax Wealth note. These how to notes are “intended to offer practical advice from IMF staff members to policy makers on important issues.” And this this was a very interesting read as you might expect.

The IMF’s How to Tax Wealth note neatly coincided with the release of the UBS/Credit Suisse, Global Wealth Report for 2023. According to the report, in 2022 New Zealand ranked sixth in the world with an average wealth of US$388,760 per adult. On the basis of median adult wealth per adult, again in U.S. dollars, we ranked 4th behind Belgium, Australia and Hong Kong, with a median wealth of US$193,060.

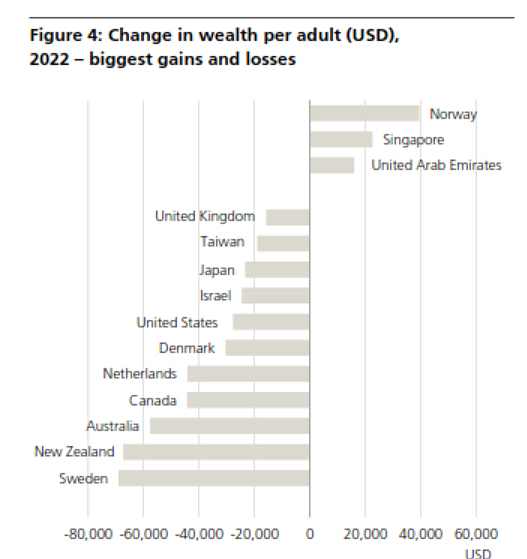

Incidentally, these rankings were after a very sharp fall from 2021 levels, where New Zealand was only behind Sweden in the biggest loss in wealth per adult.

I am genuinely very surprised to see New Zealand rating so highly for both average wealth and median wealth. On the other hand this Credit Swisse/UBS report is another example of why there’s a great debate going on around the taxation of wealth not just here, but globally.

And this IMF How to Tax Wealth note is instructive in its approach. It starts by making a very obvious point, how much to tax wealth is a distinct question from how to tax wealth. The note argues that:

“returns to capital generally should be taxed for equity and possibly efficiency reasons. and that in many countries, wealth inequality and better tax enforcement strengthen the case for higher effective taxation than in the past.”

Now the IMF doesn’t make any particular proposal about a specific level of tax, the note is basically about ‘here are things you should consider.’ But on the question of wealth taxes, it does come down pretty much against them noting,

“Improving capital income taxes tends to be both more equitable and more efficient compared with replacing them with net wealth taxes. Countries hence should prioritise improving capital income taxation over considering the introduction of wealth taxes”.

Then it talks about – in terms of strengthening capital taxes – addressing loopholes, notably the under taxation of capital gains in many countries. There’s a passing comment, that perhaps you can use a one-off net wealth tax or maybe apply it to very, very high wealth levels.

Time for inheritance tax?

But the Note also concludes “taxing capital transfers through gifts or inheritance provides another opportunity to address wealth inequality.” The IMF comments that the efficiency costs of such taxes are modest, and notes that “inheritance taxes are better aligned with redistribution than estate taxes, since exemptions and rate structures can account for the circumstances of the heirs.”

What really makes the New Zealand tax system unique is not the absence of a capital gains tax because, as David Seymour pointed out, other countries don’t have that, namely Switzerland. It’s the complete absence of taxes on the transfer of wealth, which has been the case now since 1992. That’s what makes New Zealand unique – we have no general capital gains tax together with no estate or gift or wealth taxes.

And this is an area where I think a lot more consideration needs to go into because as the IMF noted, we’ve got fiscal challenges ahead, and where might the revenue be raised from to meet those challenges.

The IMF and Climate Change Commission suggest changes to the ETS

And finally, back to the IMF again. It concluded its mission report by noting that “New Zealand’s ambitious climate goals call for major reforms,” and it referenced the Emissions Trading Scheme, having helped limit net emissions by encouraging robust reductions and removals, particularly from afforestation.

But the IMF then went on to say that “significant reforms” are going to be needed to meet domestic and international targets, and these include reducing the number of available units in the ETS, pricing agricultural emissions and strengthening the incentives for gross emissions reductions within the ETS. The IMF finally note that given the ambition of New Zealand’s first nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement, the use of international mitigation i.e.; buying credits from offshore, is likely to be required.

Now the IMF report was a week after the Climate Change Commission, and pretty much said the same thing, and advised the coalition government they should halve the number of ETS units on offer in each of the next six years. The last ETS auction did not go brilliantly. That has a flow on effect in that by reducing the amount of income from emission trading unit sales, it’s going to limit crown revenue for tax cuts.

Vale Rod Oram

It’s interesting to see a confluence of opinion happening here and an appropriate time to remember the late Rod Oram someone who was a very strong environmental journalist. I was fortunate enough to know him all too briefly after we met at a panel discussion. We’d planned on him appearing as a guest on the podcast. Sadly, with his passing that will never happen now, and our thoughts go out to his family and friends.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.