- Is the current GST threshold holding back small businesses?

- More evidence of Inland Revenue’s crackdown on non-compliance and new research fuels the debate about taxing capital.

Last week was Te Wiki o te Reo Māori, Māori language week, and coincidentally, one of the papers at the recent excellent New Zealand Law Society Tax Conference covered taxation and Māori business.

One of the more fascinating papers prepared for the last Tax Working Group was about considering the tax system from our Māori perspective.

It was therefore quite opportune and appropriate in Te Wiki o te Reo Māori, for the New Zealand Law Society Conference to cover the question of taxation and Māori business. As a supporting paper noted, in 2018, the Māori economy was estimated to have an asset base of nearly $70 billion, and it’s projected to reach $100 billion by 2030. So this is something we’re more likely to encounter as the Māori economy grows.

The presentation gave a fascinating background into what structures are developed as part of a settlement agreement between the Crown, and these post settlement government entities or PGSEs can be a very unusual mix of trusts, companies, limited partnerships and Māori authorities.

Māori authorities – a template for a difficult tax issue?

Māori authorities in particular, have very specific tax treatments and one of those includes the ability to distribute capital gains without liquidation. Which, as a presenter suggested, could perhaps be a model for companies as this is presently quite a difficult tax area. At present if a company has realised a gain then, unless it’s a look through company, you would have to liquidate the company in order to extract the gain without triggering an immediate some form of tax liability. As I said, it’s an interesting area of growing relevance. I think if you can get hold of the paper, do so.

Time to raise the GST threshold?

The accounting service provider Hnry released a poll which indicated that almost a third of sole traders in the country are choosing to earn below the median income to avoid passing on costs, because otherwise they would cross the GST threshold of $60,000 and have to register.

Their concern was that the 15% that they would have to apply to their pricing at that point was a cost they simply could not pass on.

This has sparked a debate about whether the threshold is presently too low. It was set at $60,000 with effect from 1st April 2009. Given that’s now 15 years ago, an increase seems logical and based on CPI for example, it should be closer to $87,000. It’s not unreasonable to consider an increase. As I’ve said in other episodes, we seem to have an inbuilt reluctance to regularly look at thresholds and increase them for inflation. That leads to all sorts of difficult issues cropping up within the tax system.

On the face of it, an increase in the GST threshold is not unreasonable. I think somewhere around the point where the income tax rate goes from 30 to 33%, which is now $78,100 would be appropriate and is also around the median income.

But maybe not?

But there is a counter argument, and a very interesting one too, in that perhaps if we want to have a broad base, we should be lowering the GST threshold. A good example for this counterargument comes from the UK, where they have a very high threshold of £85,000, about $180,000.

According to the UK Office for Budget Responsibility, approximately 44,000 UK businesses will deliberately not grow revenue to avoid registering for Value Added Tax (VAT), the UK equivalent of GST, and which has a standard rate of 20%.

An obvious answer is to raise the threshold, but the counter suggestion made by Dan Neidle of Tax Policy Associates is perhaps it should be lowered. He notes that in Europe the thresholds are much lower, around the €30,000 to €35,000 mark, which is around $50,000 to $55,000 here.

In Dan’s view the registration threshold creates a ‘fiscal cliff’ that some businesses find difficult to hurdle because you aren’t able to make a significantly big increase in your turnover to get past the effect on the customers because they cannot bear the cost. He suggests maybe a lower VAT rate might be one solution.

He also notes broader base for GST is important for competitiveness, because if there are people who are deliberately under-pricing themselves because they are not GST registered (as opposed to those who are) then there is a competitiveness issue. Dealing with that is going to be difficult.

I thought it was an interesting counter argument that Dan raised, but it still doesn’t get past the issue that a threshold that has not been adjusted for 15 years perhaps should be. On the other hand, comments from Inland Revenue indicate there is no desire to do so at this point. The Minister of Revenue, Simon Watts, has also said it’s not really on their agenda. So, these issues will still remain.

Going underground?

There’s one other question I think that does come to mind though. If people are deliberately limiting their income to below the GST threshold, how are they maintaining their lifestyles? Is there a cash economy and tax evasion going on here with jobs being done for cash, which won’t go through books. Now I’m not saying it’s true for every business below the GST threshold. But given that the median wage is above $60,000, you’ve got to wonder if there is some element of that going on. We shall see.

Inland Revenue ramping up its investigation activities

That leads us nicely on to another paper from the New Zealand Law Society Conference, which was opened by the Minister of Revenue, Simon Watts. He continues to impress as having a command of his brief and understanding the detail. This is not totally unsurprising, given that he used to be an accountant and began his career as a tax consultant.

Reform of FBT definitely appears to be on the agenda. Inland Revenue are focusing a lot on the near $13 billion of total tax debt that’s outstanding across various taxes (including Student Loans) at the moment. There’s a focus on what’s called high risk debt, particularly in the construction industry. Inland Revenue would be putting more resources into the hidden economy, and the Minister also mentioned the work of the Tax Debt Task Force, which is about 40 people within Inland Revenue, which is now collecting about $4 million per week of outstanding debt.

Interesting to hear this from the Minister and his comments about Inland Revenue’s enhanced enforcement activities was also supported by a presentation from Inland Revenue policy officials. The officials were referencing the search powers of Inland Revenue and two new drafts for consultation which have recently been released.

“Knock, knock”

One is in relation to what are called Section 17B notices, which are issued under section 17B of the Tax Administration Act 1994. These are information demands and they’re part of Inland Revenue’s information gathering powers. The more important one is a draft operational statement on Inland Revenue’s search powers.

Now Inland Revenue’s search powers are incredibly extensive. To give you an example, there’s a Court of Appeal case from 2012 – Tauber v Commissioner of Inland Revenue – where Inland Revenue raided six premises simultaneously. Officials obtained search warrants for these raids, but under Section 17 of the Tax Administration Act 1994 Inland Revenue officials don’t need to obtain a warrant to access property or documents. Documents in this case can include your smartphone.

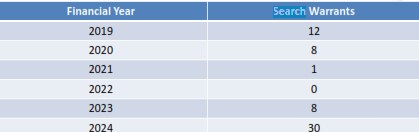

And this is where we perhaps should be starting to pay a bit more attention, because, as the paper noted, Inland Revenue’s search activity dropped off because of the COVID pandemic. Information obtained under the Official Information Act gives an extent of how this had happened.

From these stats it’s very apparent Inland Revenue is currently amping up its investigative activities. According to the presentation, officers have “hundreds of unannounced visits planned” for liquor stores.

There are over 100 audits of property developers going on at the moment and another 50 investigations underway in relation to electronic sales suppression software.

Now, as previously noted and emphasised by the Minister, Inland Revenue has had a significant funding increase given to it over the next four years. All of this shows that we can expect to see a large amount of increased activity in investigations from Inland Revenue. And we’ll also see them taking probably a far harder line in relation to collection of tax debt.

I want to repeat what I’ve said before, and which was also brought up at the conference. If you run into difficulties with tax debt, approach Inland Revenue immediately. Don’t put your head in the sand. It’s always best to front foot it and contact Inland Revenue. If you’ve got a realistic approach to getting out of your tax debt, it will be prepared to put together a plan that enables that to happen.

High earner tax rates – New Zealand in context

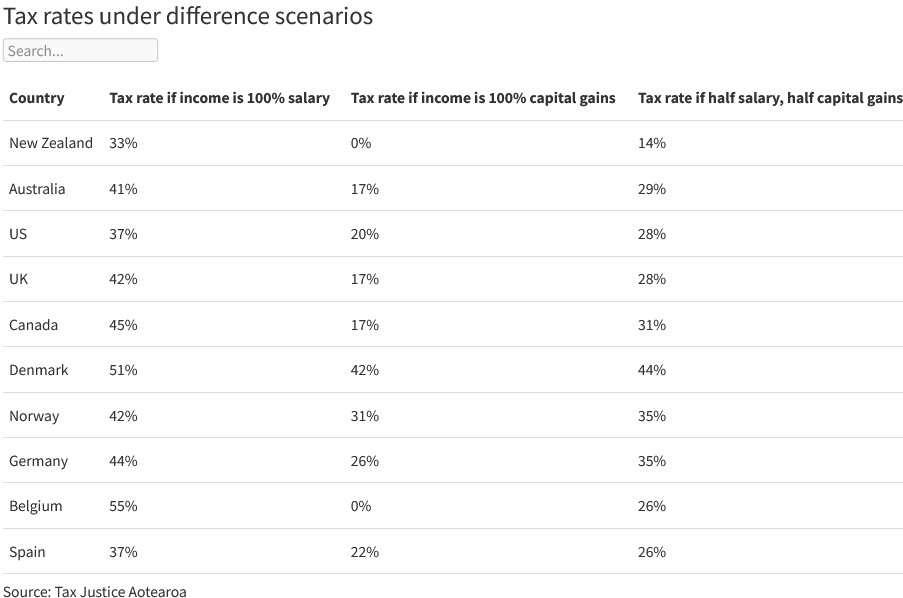

The debate around the taxation of capital continues with a RNZ report involving a Victoria University study, commissioned by Tax Justice Aotearoa, which looked at how much tax someone earning five times the average New Zealand wage (that’s roughly $330,000) would pay in nine comparable nations. Those nations include Australia, Canada, the US, the United Kingdom and five European countries – Belgium, Germany, Norway, Spain and Denmark. The study found that there was a quite significant difference between the tax payable in New Zealand and that payable overseas, particularly in when considering capital gains.

Tax Justice Aotearoa are using this data as a counterargument to fears there would be mass capital flight if we introduced some form of wealth taxes. When I was interviewed on RNZ’s Morning Report about the story I agreed with the basic premise of this counterargument. That’s not to say there won’t be capital flight. There will because people’s capital is mobile and there will be people with the resources to migrate into tax havens where there are very low rates of income tax and little or no capital taxes

But not all capital is mobile. Any property they held in New Zealand would still be subject to any form of taxation because the rule around the world is that property is always taxable in the country in which it is situated even if it is owned by a non-tax resident.

A false debate premise?

I also told Morning Report that the premise of the debate seemed slightly off in that if we have a capital gains tax or form some form of taxing capital, we will therefore have capital flight, so we shouldn’t do that. In my view this is incorrect, the reason we’re having the debate about taxing capital is not because other jurisdictions have such taxes so why don’t we? This frames it as a question of equity and fairness.

The issue is the coming demographic crunch and also the more immediate crises we’re now seeing regularly of the impact of climate change. How do we have the funds to deal with an ageing population, the associated health costs with that, and the impact of climate change. Last year’s Cyclone Gabrielle and the Auckland floods were incredibly expensive events, so this debate isn’t going to go anywhere because it fundamentally revolves around the question “We have costs building up. How are we going to fund those?” And that’s a debate which will continue.

There isn’t a magic bullet here in terms of one tax is superior to all others in my mind. We just have to look at all the options and then decide how we will move forward. But I think it’s false to say, well, we can’t do anything because people’s capital will flee. That’s doesn’t say much, by the way, for the many citizens of New Zealand who built their livelihoods and have long-standing roots here, but as I said also seems to sidestep the issue as to why we’re having the debate in the first place.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.