- How to deal with recipients of paid parental leave with tax underpayments

- A bizarre tax avoidance case from the UK involving snails

In line with other government agencies, Inland Revenue is required to produce a long-term insight briefing once every three years. These briefings are intended to

“…help us collectively as a country think about and plan for the future. They do this by identifying and exploring long-term issues that matter for our future wellbeing. Specifically, [briefings] are required to make publicly available:

- information about medium- and long-term trends, risks and opportunities that affect or may affect New Zealand society, and

- information and impartial analysis, including policy options for responding to the trends, risks and opportunities that have been identified.”

This is Inland Revenue’s second long-term insight briefing, its first one released in 2022 was on tax, foreign investment and productivity and that was a fairly chunky topic. But this time around it’s proposing to take on a bigger topic “what broad structure of the tax system would be suitable for the future.” What it would do is look at this topic by reviewing our tax system through the lenses of what is the tax base and what regimes apply.

As part of the initial stage of consultation for this topic Inland Revenue has released a 50 page briefing document giving a background on the whole process. The briefing summarises the current state of the New Zealand tax system and the options for consideration. Chapter one gives a complete overview of the current system. Chapter two then gives options for a future tax system and looks at international perspective. The final chapter summarises the topic and the approach to be taken by the briefing.

A mini-tax working group review

There are a lot of interesting insights in this paper, because in essence it’s similar to the scoping paper usually prepared by a tax working group at the start of a review before the group gets into detailed analysis of particular aspects of the tax system. The briefing is a therefore a handy high level summary of the current state of the New Zealand tax system.

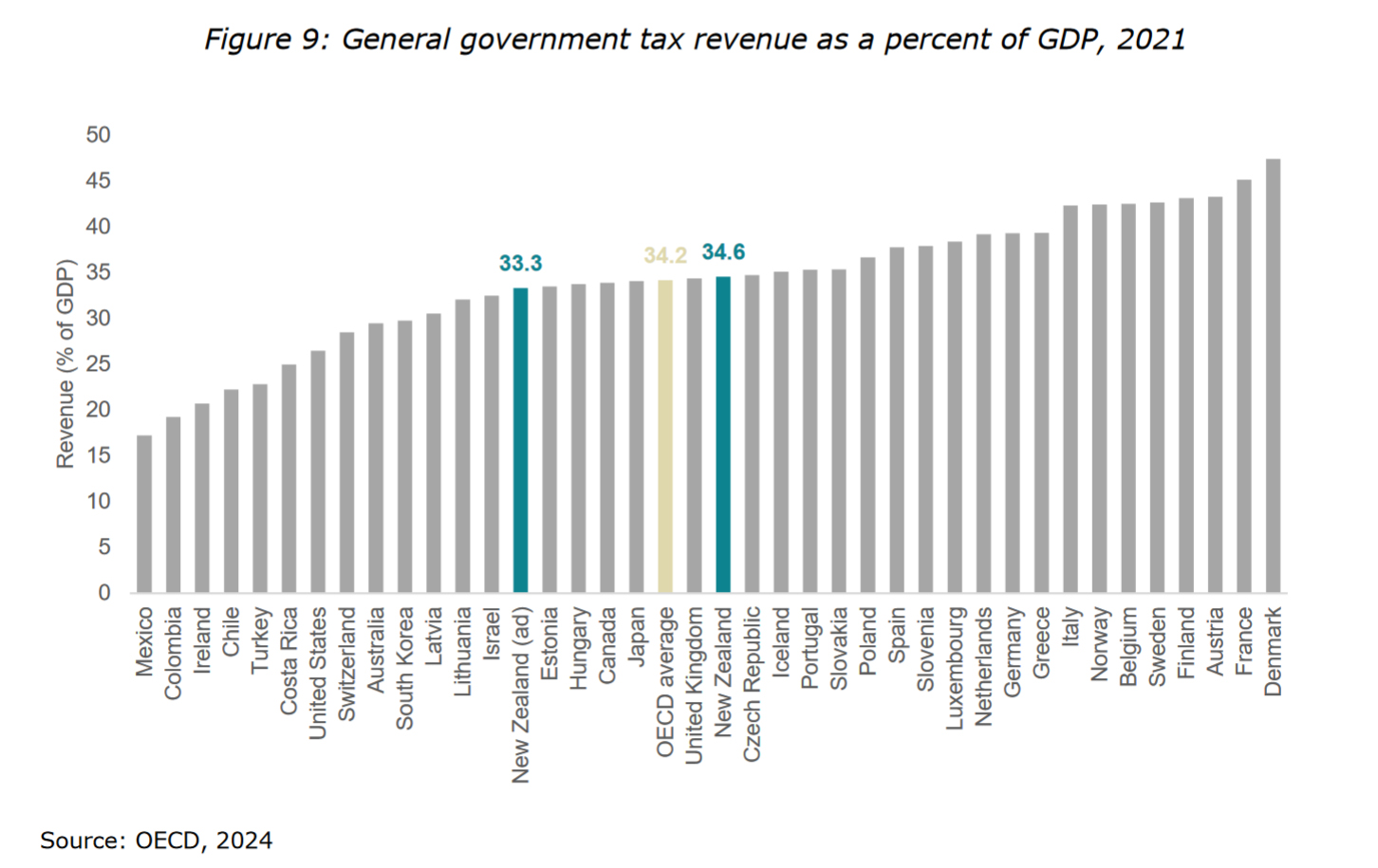

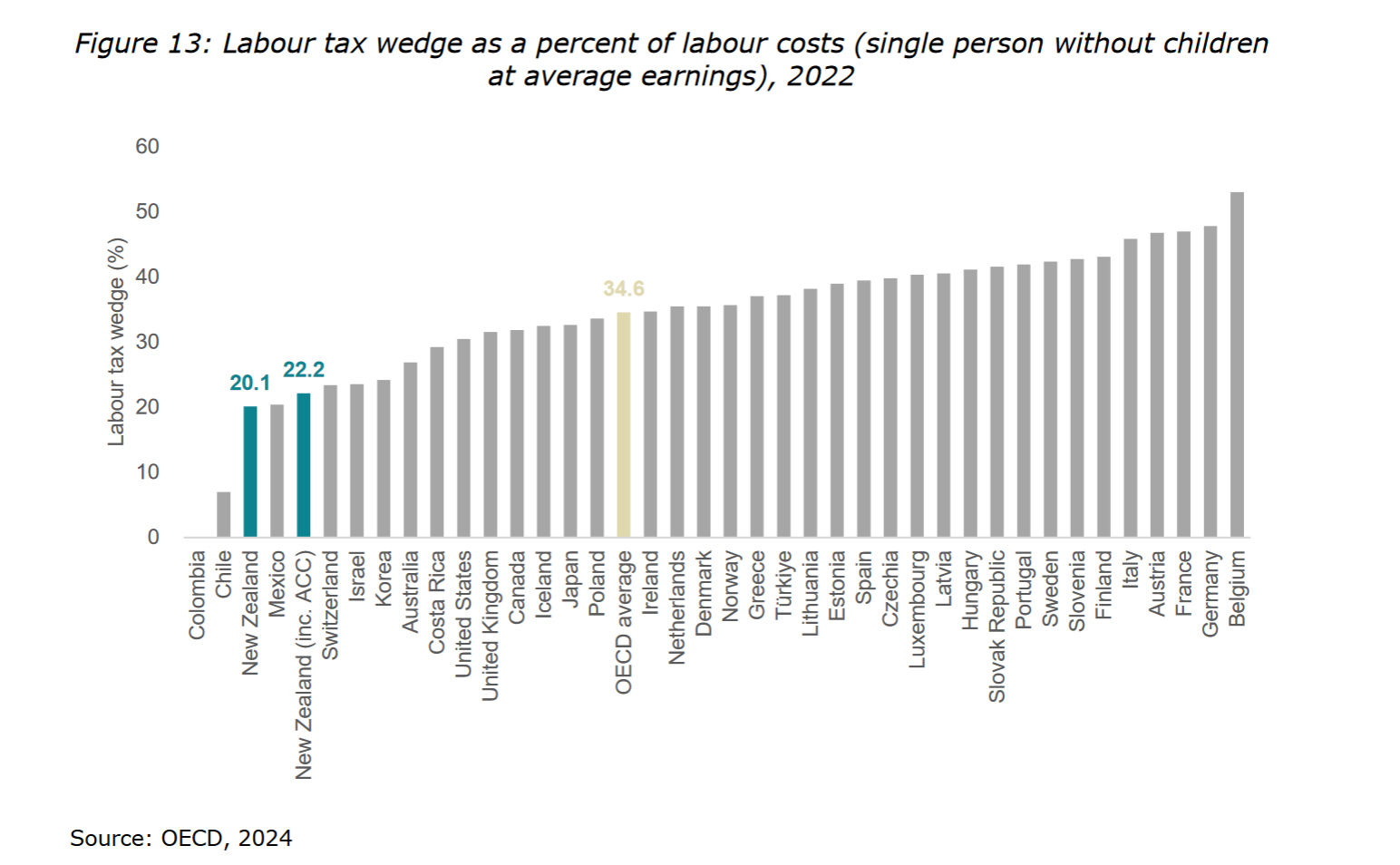

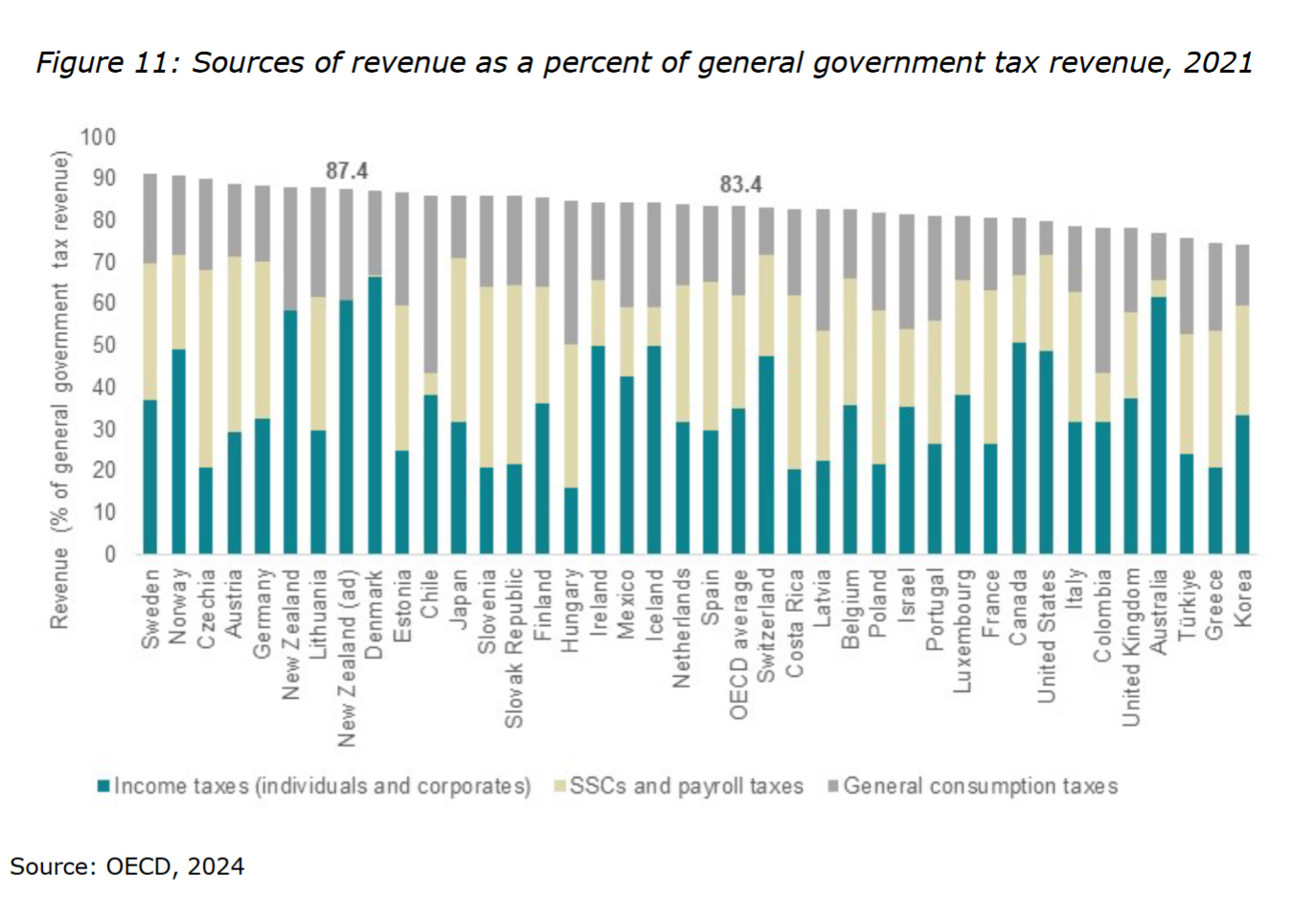

In summary, the level of tax revenue we currently raise relative to the size of our economy is pretty close to the OECD average. It’s in the composition of tax revenue. It’s where it gets interesting. We are almost unique in the OECD in not having any significant specific taxes on labour income such as social security contributions or payroll taxes.

Taxing labour…lightly?

Furthermore, quite a few of other OECD tax systems have what they call a schedular tax system, which means in some cases they tax capital income such as dividend, and in some cases capital gains at lower rates than taxes on labour. As a result, many OECD countries have a higher tax burden on employee labour than New Zealand.

To give an example, the UK has a 20% basic tax rate, but employees also pay National Insurance Contributions above a certain threshold (8% on income between £242 and £967 per week and 2% above £967 per week). Employers pay 13.8% on all earnings over £175 per week. By contrast we have no such taxes which means we have one of the lowest tax wedges in the OECD.

Also, where we stand out is we raise more than the OECD average on general consumptions and that’s because our GST is one of the most comprehensive in the world. We also currently have a higher company income tax rate than the OECD average.

The paper notes some concerns noted about high effective marginal tax rates on inbound investment. I have to say I do wonder whether the small size of our economy and its isolation is more of a factor than tax in attracting inbound investment.

And finally, and this is highly ironic and also relevant if, you just opened your rates bills and the comments from the Prime Minister earlier this week, New Zealand raises more than the OECD average from recurrent property taxes, mainly through local government rates.

Building fiscal pressures

As part of the background the paper explains the various fiscal pressures building up. This is something we’ve talked about before, and we’ve frequently referenced, Treasury’s He Tiro Mokopuna 2021 statement on the long-term fiscal position. The well-known pressures building in in relation of our changing demographics, rising superannuation and health costs are all mentioned again.

So too is climate change, but more in passing, although personally I think that’s the one the impact of which is going to land first for most people as we saw last year in the wake of Cyclone Gabrielle. Suddenly, climate change is not an abstract thing with targets for 2050. It’s here and now. Remember Auckland ratepayers, for example, we got a $400 million bill as a result of buying out properties rendered uninhabitable by the Anniversary Weekend floods and Cyclone Gabrielle.

A suitable tax system for the future

The paper discusses what would you do in terms of meeting these pressures. Do you expand the tax base by adding new taxes or what about increasing tax rates? The paper mentions that there are limitations about raising tax rates which is not always as straightforward as you might think. For example, we raised the rate of GST from 12.5% to 15% in October of 2010 and GST as a result is a very significant tax because our system is so comprehensive.

But GST comes at the price of being very regressive for people on lower incomes. How would you deal with that? And the paper, by the way, references an IMF Working Paper on a progressive VAT/GST which I mentioned recently.

There was also an interesting comment I’d like them to know more about in relation to company tax. The paper notes that we raise a relatively high amount of revenue from company income tax as a proportion of GDP compared with other countries.

It notes this “may be partly attributable to the level of incorporation.” I’d be interested in knowing how much more company incorporation goes on here relative to other OECD countries. I think our imputation tax system is also a factor in why we pay relatively high amounts of tax relative to other jurisdictions.

What the briefing does reinforce is something I think is agreed within the tax community that there’s pretty much little scope for increasing company income tax rates. There’s always a lot of talk about that, but I don’t think there’s much scope for actually doing so.

“New Zealand is unusual among OECD countries in not having a general tax on income from capital gains”

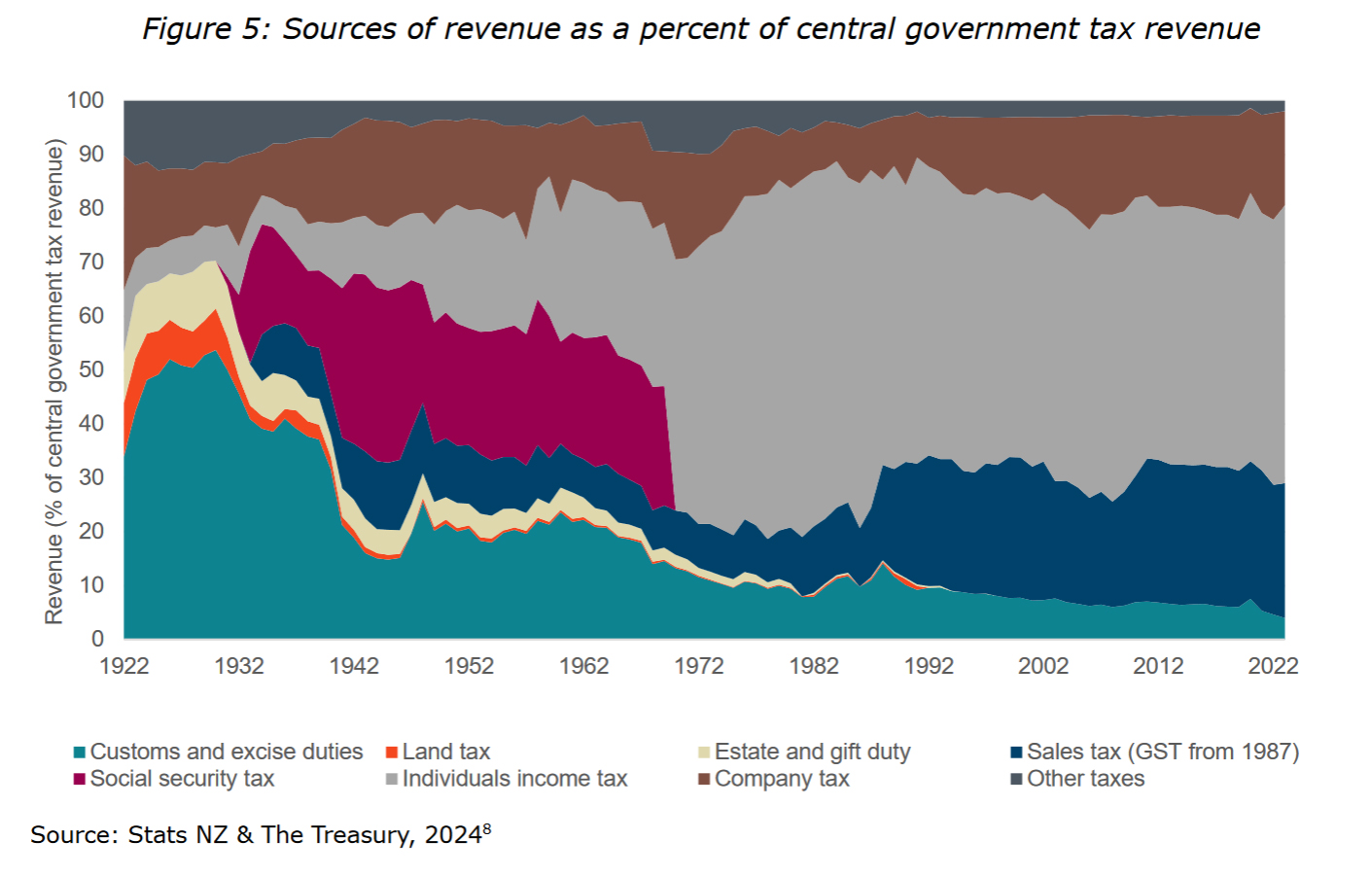

Unsurprisingly the paper considers the question of taxing capital, as part of reviewing the composition of taxes in other countries. There are a lot of interesting graphs and stats are in this section including an excellent section summarising the historical changes in the composition of the tax base over the past century.

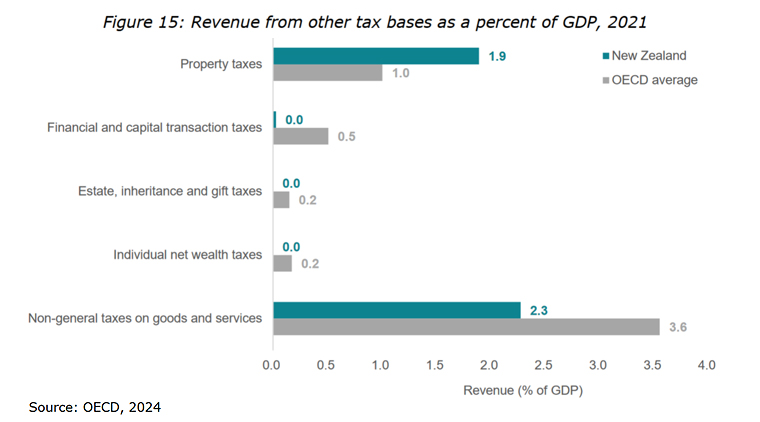

As I mentioned, we raise more revenue as a share of GDP from recurrent property taxes compared to the OECD. In 2021 it amounted to about 1.9% of GDP. B comparison, the average in the OECD is 1%, ranging from 0.1% of GDP in Luxembourg to 3% of GDP in Canada.

On the other hand, we don’t raise anywhere near the same level as other OECD countries from taxes on financial and capital transactions, estates and gifts. I mean, many countries have a combination of estate taxes, gift duties, capital gains, taxes and wealth taxes. According to the OECD data taxes on estates, inheritances and gifts raised an average of 0.1% of GDP in 2021. That seems a surprisingly low number, although it rose to 0.2% in 2022. This take is starting to rise as the Baby Boomers, the richest generation in history are starting to pass on. In the UK Inheritance Tax, which is a combined estate and gift tax, is now over 0.3% of GDP (£7.5 billion) and rising.

What about corrective and windfall taxes?

The paper gives a background on the possible options which might deal with future cost pressures. Its focus is going to be on revenue raising taxes. The final briefing will not examine taxes that are primarily about changing behaviours (so called “corrective taxes” such as excise duty, particularly in relation to tobacco. It will not discuss environmental taxes which are another form of corrective taxes. All taxes change behaviour in different ways and I think considering the behavioural impact of certain types of taxes would be useful

The final briefing will not consider windfall taxes, which have recently popped up in discussion in relation to supermarkets and the banks. Such taxes are one-off in nature and frankly, a reactionary tax to a set of events. If the concern, correctly in my view is about responding to the pressure of ever increasing costs, then windfall taxes are not in that context a sustainable addition to the tax base.

All in all, this is very interesting and pretty digestible reading. Consultation is now open until 4th October, so my suggestion is get reading and start submitting.

A baby and a tax bill…

Moving on, Inland Revenue has mostly completed its year-end auto assessment process for the majority of taxpayers’ income for the March 2024 tax year. Subsequently, it’s emerged that some 13,261 recipients of paid parental leave, about 27% of all such recipients have finished up with a tax bill. This is causing some concern because in some of these cases, these bills are quite substantial, amounting to several thousand dollars in some cases which have to be paid.

Paid parental leave is taxable and subject to PAYE. What seems to have happened is that people haven’t factored in the effect of their other income, for example they may have continued to work reduced hours in their main employment while also receiving paid parental leave. Consequently, because PAYE is designed around one person, one job per year the parental leave has been under taxed. But this only emerges as part of the end of tax year wash up. You can deal with this by using a secondary tax code, but that often goes the other way and leads to over taxation during the year.

Tailored tax codes

An answer to all of this, and also as a means of collecting the tax paid would be a tailored tax code. Tailored tax codes are ideal for an employee with other sources of income which aren’t subject to PAYE such as overseas pensions. What you do is advise Inland Revenue of these other sources of income and ask it to adjust your PAYE tax code taking into effect this other income. It’s then taxed during the year through PAYE. By the way, this also is a good way of bypassing the provisional tax system.

This approach is something I saw a lot of when I worked in Britain. HM Revenue and Customs adjusted tax codes for the equivalent of New Zealand Superannuation and used adjusted tax codes to collect underpayments of tax for prior years. If you underpaid one year, your PAYE code for the following year would be adjusted to collect the underpaid tax. I think this is probably an easier system than expecting lump sum payments.

My view is Inland Revenue could make a lot more use of tailored tax codes and should do so proactively. It has the information to know when someone has started a second job or starts receiving paid parental leave. It can then contact that person and ask they want to have a secondary tax code or a tailored tax code. This may already be happening but people with new babies have plenty going on, so this sort of admin detail just slips off the radar. I think it’s something where Inland Revenue systems ought to be good enough to be able to actively encourage people to make greater use of these codes.

Snail farm in city office sparks tax avoidance probe

Finally, and returning to an earlier topic, rates, there’s a story from the BBC about a quite flagrant tax avoidance scheme in the UK. The story involves a commercial building in Liverpool and what’s happened is this building has been home to a snail farm for more than a year. The firm renting the premises has told Liverpool City Council that because the building is being used for agricultural use that part of the building is exempt from business rates. Otherwise, the rates bill would be about £61,000 for the whole building.

Understandably, Liverpool Council’s not impressed, and neither are other snail farmers. (Apparently snails retail for £14 a kilo). They think the scale of the operation isn’t realistic because according to the owner there are only two snails in each crate which has been done to avoid “cannibalism, group sex and snail orgies”. (Yikes!)

This seems a fairly flagrant tax avoidance case. And it’s caught the eye of Dan Neidle of the UK tax think tank Tax Policy Associates. As he notes you’d think this sort of thing would be struck down quite easily by the courts but not so. There doesn’t appear to be a specific anti-avoidance rule in the relevant legislation, and it appears that there’s quite an industry around so-called “business rates mitigation”. Astonishingly, a recent case involved a Crown organisation Public Health England attempting to bypass rates through one of these schemes. Dan has suggested that the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, (Finance Minister) Rachel Reeves, put in place legislation to strike this sort of activity down.

An opportunity here?

Under our rating legislation here I think that a similar scheme probably wouldn’t work. Based on what I understand our rating approach seems to be a bit more comprehensive. But one of the things I know about working in tax is that where people perceive there’s an opportunity to, let’s say, push the envelope, they will do so.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.