- A big tax break for build-to-rent developers

- The role tax has played in the housing crisis

- Clarifying the treatment of donations to private schools

Transcript

Housing Minister Megan Woods recently made a surprise announcement that blocks of at least 20 new and existing build to rent flats will be exempt from the interest deductibility limitation rules in perpetuity if they offer 10-year tenancies. Currently, build to rent flats would only qualify for the exemption from interest deductibility rules if they are new builds and then only for 20 years.

This is quite a significant change clearly aimed at the developing build to rent market, which after the announcement of interest deductibility limitation was made last year was quite concerned that the sector would be very hard hit by the proposals. During the group discussions and consultation that went on with Inland Revenue in the run up to the release of the relevant legislation, these concerns came across very strongly from the build to rent sector.

Obviously, they’ve continued lobbying in the background and have won this concession. This is a big win for the sector as it will probably greatly shake up the rental market over the long term. It gives it security of supply and therefore for financing. But it’s also a win for tenancy advocates who have been pushing there should be longer tenancies available to renters similar to what we see in continental Europe.

It’s also worth noting that this new exemption will apply to existing properties. Therefore, if you take an existing property and convert them into 20 apartments or flats, then you qualify for this permanent exemption. Again, last year there was quite a bit of discussion over what constituted a “new build” and conversions were high in the list of matters under consideration.

On the other hand, the move does further sideline the mum and dad type investors who are currently a large part of the rental market. And at the moment they will definitely be left hoping for a change of government next year. Overall, this change seems a smart policy to boost the growing rent to build sector, but also give greater protection to tenants.

The reasons for very high house price inflation

Moving on, exactly why house price inflation in New Zealand has been so high has long been a matter of debate. The Multi-Agency Housing Technical Working Group, which consists of members from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Treasury has been studying this issue in some detail.

And on Thursday the Housing Technical Working Group released a report on the housing system based on a close look at the housing development system in Hamilton, Waikato area.

Now the group’s key conclusion was:

“…a combination of a global decline in interest rates, the tax system, and restrictions on the supply of land for urban use have led to a large change in the ratio of prices to rents and are the main cause of higher house prices in Hamilton-Waikato, as well as other parts of Aotearoa New Zealand, over the past 20 years.”

The report has some interesting insights on the road tax matter. The report starts from the pretty standard theory that a neutral tax system is one that treats different economic activities equally. However, the report notes that “New Zealand’s tax system is not neutral” and there are a range of tax distortions that affect house prices, land prices, rents and construction costs.

According to the report, the most important distortions in the tax system are firstly imputed rent, that is the rent owner occupiers effectively pay themselves is not taxed, whereas other forms of income from investments are taxed. This is a very controversial point and conceptually counter-intuitive for owner-occupiers. But it is an approach that the Netherlands has adopted to tax housing on an imputed rental basis.

Secondly, capital gains are often not taxed, whereas other forms of income are. Well, this podcast is a broken record about the distortions the lack of a comprehensive capital gains tax produces.

Then thirdly, the GST is charged as a lump sum when a house is built and is charged on maintenance costs and rates but is not charged on rents. This is a very interesting point and not one that I’d actually considered in much depth.

The consequences of these distortions is the first increases the incentive for people to live in bigger or better houses than otherwise. We see that in New Zealand, new builds are the second or third highest in the world in terms of area.

The report expands on the matter of the first and second distortions, that the lack of capital gains and imputed rent also increases the investment value of housing relative to other investments. This is a well understood point which means those resources devoted to owner occupied housing “yield untaxed shelter in perpetuity as well as untaxed capital gain”. If on the other hand, you put money in the bank or in shares you will be taxed on the income. Finally, as is well known and is one of the reasons for the interest deductibility limitation rules, investing in rental housing yields tax free capital gains for those who hold property long enough.

The report concludes these tax distortions have caused a higher price to rent ratio in New Zealand than under a more neutral tax system. The group also reaches the interesting conclusion that New Zealand is “closer to restricted land supply than abundant and therefore we conclude that these income tax distortions are likely to have driven house prices higher rather than increasing supply and reducing rents.”

The commentary on the impact of GST is interesting because as I said, not many of us have actually thought about that and how it might play out. What it says is that the overall role of GST extends well beyond the “…direct impact on construction costs and includes a complex array of interactions stemming from the fact that GST is not charged on rents but is charged in other goods and that GST is charged only on some land transactions. The report notes “Assessing the overall impact of New Zealand’s GST on house prices is a possible area for future research.”

The report includes an interesting table estimating the impacts of tax distortions on house values for each type of buyer. The report notes the tax distortions were relatively small in 2002 when interest rates were much higher but by 2021, the impact of these tax distortions “had grown significantly”. The report further noted that in a low interest rate environment, the tax distortions were significantly amplified.

Table 2 Impacts of tax distortions on house values for each buyer type

| Estimates with current tax settings (Estimates with ‘neutral’ tax settings) |

||||

| Date

Inflation rate Interest rate* |

Q2 2002

π = 1.8% i= 5.6% |

Q2 2011

π = 2.5% i= 5.4% |

Q2 2016

π = 2.1% i= 4.1% |

Q2 2021

π = 2.0% i= 3.5% |

| Landlord

Equity financed |

$169,031

($114,495) |

$289,709

($185,365) |

$438,582

($261,808) |

$680,901

($379,377) |

| Landlord

60% debt** |

$164,869

($112,175) |

$276,188

($179,021) |

$435,601

($261,950) |

$431,979

($400,966) |

| Owner-occupier

Equity financed |

$189,161

($89,753) |

$278,309

($141,369) |

$367,980

($185,213) |

$516,949

($255,797) |

This is a very interesting report which feeds into the ongoing debate about housing. I think it underlines a constant theme of this podcast that we need to change our tax settings, settings around the taxation of capital and in particular, housing. Of course, Professor Susan St John and I would be pointing to the fair economic return methodology as one option for starting to take some of these tax distortions out of the market.

GST and private schools

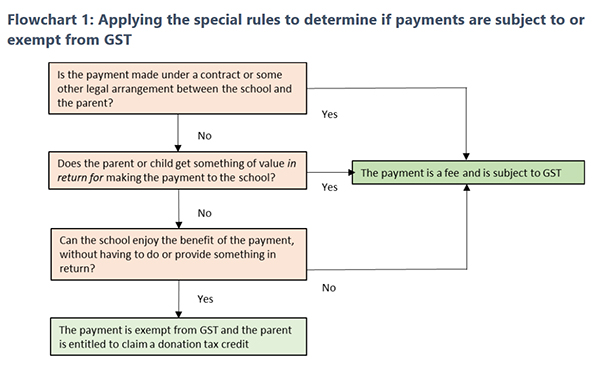

And finally, private schools have been in the news recently, largely because of the revelations about the behaviour of the newly elected MP for Tauranga. Quite by coincidence, this week Inland Revenue has released a draft Question we’ve been asked on the GST and income tax treatment of payments made by parents to private schools. This also comes with a handy flow fact sheet as well which has a useful flowchart which explains how the rules apply.

Something else to keep in mind are the special rules for calculating GST on school boarding fees. Where students have arranged to board at the school for more than four weeks, the school charges GST at a lower rate (9% or 60% of the standard rate) to the extent the boarding fee is for the supply of domestic goods and services.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!