- Taking GST off food

- IRD’s construction sector initiative

- Te Pati Māori’s tax policy

This week has been a very busy week politically in the tax world, starting with a Cabinet reshuffle after David Parker relinquished his role as Minister of Revenue. In his own words, he felt that his position had become untenable in the wake of the decision by Prime Minister Chris Hipkins to rule out a wealth tax and capital gains tax for the foreseeable future.

Parker has been replaced by Barbara Edmonds, who has an interesting background in that she worked in Inland Revenue for some time prior to becoming an MP in 2020. In 2016 she was seconded from Inland Revenue to work as private Secretary to the then Ministers of Revenue, first Michael Woodhouse and then Judith Collins. (This is actually something that happens quite commonly with Inland Revenue officials working closely alongside other ministerial officials). In 2017, she then became a political adviser to Stuart Nash after he became Minister of Revenue. So, she’s got a very good background on the portfolio.

One of the things I think she might read with some amusement is what’s called a Briefing to Incoming Minister. Whenever there’s a change of minister the relevant department prepares a briefing to that minister, setting out their role and the key challenges ahead for as the particular ministry. I suspect Edmonds has been involved in preparing several of those. But this time she will be receiving one as recipient. The change is probably what you might call unforced, but it’s part of the fallout of the decision to not continue with the down the path of imposing a wealth or capital gains tax.

Signs of strain in the construction industry?

Moving on Inland Revenue has started a pilot programme to provide some support for those construction industry, or customers in the misguided terminology, in my view, of Inland Revenue. It’s intended to provide “tailored assistance” to help those in the industry through various stages of business. The intention is to have “meaningful discussions” with taxpayers in that industry about the business, how they’re doing, offering guidance and support about tax and entitlements. These will also involve “promoting the benefits of having a tax agent or bookkeeper”.

Long-time listeners of the podcast will know that when Inland Revenue was in the early stages of its Business Transformation program, tax agents felt, with some justification, that they’d been shut out of the process. It’s now interesting to see that Inland Revenue has realised that tax agents actually have a key role to play in the system and are encouraging their use. Good to see.

This is an interesting initiative by Inland Revenue. It probably speaks to strains that they are seeing within the construction sector, slow payments, people getting behind in tax debt, tax returns, etc.. This pilot program is an initiative to front foot those issues. I’m all in favour of Inland Revenue taking steps like this and moving forward I think it would be wrong to ever adopt the idea that any call from Inland Revenue is a bad call, that you’re in trouble. Sometimes they come in and they may have some suggestions about what to do and how to manage scenarios which can be very constructive.

In every case I’ve ever dealt with, if you front foot issues around slow payment, failure to file returns, whatever with Inland Revenue, you will find that they are receptive to those advances. A key part of their job is to promote voluntary compliance and help the smooth running of the system. As part of this it does matter if people can build trust that the Inland Revenue is actually, if not entirely on your side, a rather fairer referee than people might expect.

Te Pāti Māori go big on tax reform

Moving on, as I said, it’s been a busy week politically. We’ve had the effective resignation of David Parker as Minister of Revenue, and then yesterday Te Pāti Māori released their tax policy. Firstly you could not accuse them of being very limited in their ambition. In fact it’s a very ambitious policy.

The executive summary begins “We have a broken tax system in this country which has fuelled extreme wealth inequality that is only getting worse.” So, that’s the starting base point. In my view there are definite strains in the tax system, and we are seeing more and more of those emerge.

The key proposals are for GST to be removed from “kai”, lower income tax for those low incomes which is to be paid for by increasing income tax on those earning more than $200,000 and raising the company tax rate from 28% to 33% (also a Green Party proposal).

The key revenue raising measure, which is probably no surprise, is a wealth tax. As you know the Green Party also proposed a wealth tax on net wealth over $2 million. Under Te Pāti Māori’s proposals a 2% wealth tax on net wealth over $2 million is the starting point. However, if your net wealth is over $5 million, the rate is 4% and then if it’s over $10 million the rate rises to 8%.

From the work done for Treasury and Inland Revenue on the Government’s abortive wealth tax we have some idea of how many people might be affected by a wealth tax. An entry threshold of $3 million would have affected 99,000. The final design modelled for the Government was based on a $5 million threshold which would have affected 46,000 people. The report estimated the number of taxpayers who would have had net wealth in excess of $10 million as 16,000. So, it’s a pretty targeted group.

Te Pāti Māori have some fairly ambitious numbers on this. They believe that they their wealth tax would raise $23 billion per annum, which is a pretty significant amount of tax, in fact just a bit over 20% of the current tax take.

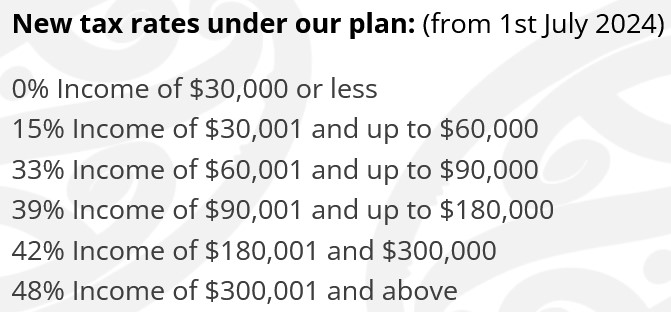

The wealth tax would be used to set income tax thresholds as follows:

Te Pāti Māori estimate 3.8 million people would benefit from their proposed tax cut package. They’re also, as I said, removing GST from “kai”. How that gets defined is going to be interesting and we’ll talk more about that in a minute.

There are several other new tax proposals. A proposed Overseas Financial Transfer Tax of 2%. This is to apply to overseas companies operating in New Zealand and will be additional to the company tax rate, which by the way, they propose increasing to 33%. This seems to represent some form of withholding tax. I imagine there might be quite a few double tax agreement issues involved in this.

A Land Banking Tax will be payable on all land that has not begun to be developed within four years of purchase. In addition, there will be a Vacant House Tax which would be payable on all properties that do not have a tenant after a six-month period.

Tackling tax evasion

One other interesting proposal is to tackle tax evasion which they say is “approximately $7 billion” annually. I think this number might also include tax avoidance which has an important distinction from tax evasion. Te Pāti Māori propose to invest $500 million into adequately resourcing the Serious Fraud Office and Inland Revenue to investigate and address these issues. This would be a colossal funding boost to both organisations. In the case of Inland Revenue, it would more than double its capacity and it would be a massive lift also for the Serious Fraud Office. So that’s an interesting one proposal, which is probably off the radar, but might be one of those things that actually gets pushed through when parties sit down to negotiate after the Election.

A Government leek?

Te Pāti Māori proposals got overshadowed by an apparent leak from within the Labour Party, immediately denied, that they were considering removing GST from food.

I’m often asked about the question of removing GST from food because on the face of it, it seems a fairly obvious thing to do. This happens in Australia and in many other GST/Value Added Tax (VAT) jurisdictions around the world food is zero rated to use the correct terminology. So if it can be done elsewhere, why can’t we do it here?

I’m in the group of tax policy advisers who are pretty much unanimous in thinking that after establishing a comprehensive GST, which included everything, we shouldn’t be tinkering too much around the edges and introducing exemptions, particularly ones such as food, which will turn out to be pretty costly. Te Pāti Māori estimates the cost of GST free kai to be between $3 and $5 billion.

Marshmallows and Max Jaffa

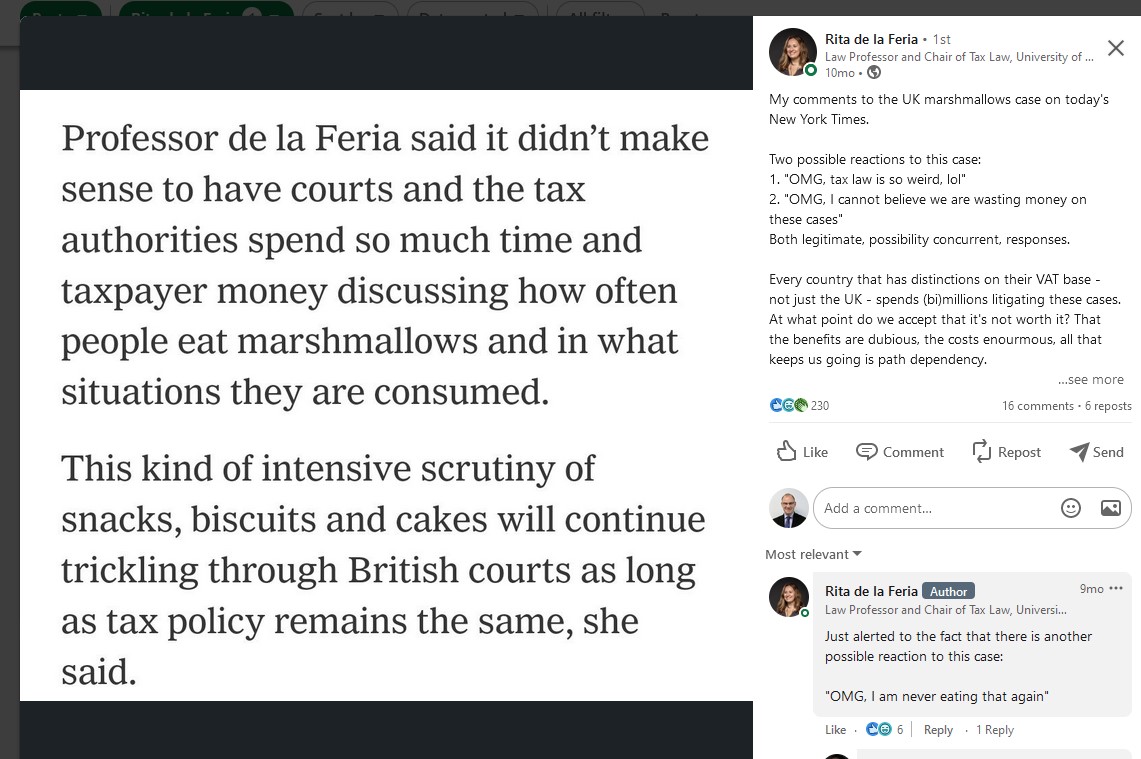

Our objections are firstly around the principle of not upsetting the purity of GST (and it’s one for which we get a fair bit of flak). There are actually really practical reasons around this matter. Like it or not, there are definitional issues around here and listeners to the podcast will recall when I discussed a recent UK VAT case involving marshmallows which because of their unusual size they qualified to be zero rated. There’s also the famous Max Jaffa VAT case which I explained on TVNZ on Friday.

Over in Australia they’ve had zero rating issues boundary issues around bread. In every jurisdiction around the world with GST/VAT these issues all arise. So, thinking because this is such a good thing to do, doesn’t bypass those problems.

Secondly, as I mentioned, it’s expensive. What do you do elsewhere? You’re giving away revenue as a tax cut so that’s got to be funded. In Britain, for example, the standard rate of VAT is 20%, and across Europe you will see rates of 20-25% and more as common. This trade off has to be taken into consideration, which is not considered too much by proponents.

And then finally, there is a very flawed assumptions that the full benefit of a cut will flow through to the customers. There is little evidence of that actually happening. The Tax Working Group looked at this issue and was not a fan.

Interestingly, the evidence it gathered from Europe was that whilst the majority of any general rate in cut in VAT (for example reducing the rate to 12.5%) did flow through to benefit consumers, in relation to specific incentives the estimate was that only 30% passed through.

Podcast listeners will know that I’ve cited Dan Neidle and Tax Policy Associates in the UK’s review of a couple of initiatives where VAT was reduced to zero. In one case the reduction in e-books, they saw no benefit passing through to consumers.

Well meant but poorly targeted policy?

Removing GST from fresh fruit and vegetables is a good example which VAT/GST specialist Professor Rita de la Feria of the University of Leeds has pointed out is a well-meant but ultimately poor policy.

Ultimately in my view the question about wanting to do something about cutting GST comes back to giving people some more money. Now we can do that through income tax cuts or with properly targeted payments to assist the low-income groups that are hardest hit.

This is something for our politicians to actually front up and address, because when you read the officials’ analysis (and it was in the papers relating to a tax-free allowance), they usually suggest it’s better to give more targeted reliefs in the form of direct benefits rather than widespread initiatives. And every time the politicians shy away from such proposals for whatever reason, maybe they think there’s no votes in it or whatever, but the principle still stands.

So, it will be interesting to see what Labour’s actual tax policies will be, whether they will run with removing GST on fresh fruit and vegetables. The proposal certainly seems popular.

But I’m actually quite glad to see political parties thinking big about tax and saying we need to do something radical in the area. Te Pāti Māori is the latest alongside Act, the Greens and TOP. All have made serious suggestions about significant changes to our tax system, whereas the two main parties seem to be just offering little more than fiddling around the margins. Anyway, we’ll no doubt see more in the coming weeks. And as always, we will bring you the news as it develops.

That’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.