Terry Baucher outlines his three key impressions from the Tax Working Group’s Submissions Background Paper

There’s a lot to chew over in the Tax Working Group’s (TWG) Submissions Background Paper released on Wednesday.

The relative narrowness of our tax base, the implications of the gig economy and technological change, and the international pressure for lower corporate income tax rates to name a few. For me three areas stand out: the scale and potential impact of demographic changes underway; the potential role of environmental taxes; and the taxation of capital and savings.

But my biggest initial impression is how the decision to exclude consideration of taxing the family home, or the land underneath it from the TWG’s terms of reference, hangs over the paper like Banquo’s Ghost.

A demographic timebomb?

My first major conclusion from the Submissions Background Paper is how much the coming fiscal pressures of an ageing population really need to be kept front and centre when considering changes to the tax system.

The paper begins by setting out key risks and challenges for the tax system over the next 30 years or so. A key baseline is the Government’s fiscal objective of maintaining taxation at the historical level of 30% of GDP over time. At the same time the paper identifies the pressure of changing demographics and an ageing population. For example, for the current year to 30 June 2018 New Zealand Superannuation is expected to cost $13.7 billion, “more than all other benefit payments combined”.

As a result of these pressures, the paper projects the Government will have a primary deficit of 1.2% of GDP by 2030 (about $3.4 billion based on current GDP), rising to 4% of GDP in 2045 or $11.4 billion based on current GDP. Very clearly then as the paper warns;

“If the Government is to continue providing healthcare and superannuation at current levels, then the level of taxation will need to increase, or spending on other transfers or publicly provided goods and services will need to fall.”

Against this backdrop the work of the TWG and the recommendations it will make are hugely important. Change is coming and therefore the tax system needs to be ready for that.

Taxing the environment

The environment is hugely important to the New Zealand economy whether it is liveable or for our two largest export earners agriculture and tourism. New Zealand is committed to reducing net emissions 30% below 2005 levels by 2030 so the Background Submissions Paper suggests;

“Using the tax system to ensure that consumers and producers face the costs of emissions and other environmental harm could be one way we can meet our international obligations.”

The paper also notes that New Zealand had “the second highest level of carbon emissions in the OECD per dollar of GDP in 2017”, an alarming statistic which suggests action is needed sooner rather than later if we are to maintain the idea of being clean and green.

At present environmental taxes such as petrol excise duties and waste levies amount to approximately 4.2% of total tax revenue, or about 1.3% of GDP. This puts New Zealand at the low end compared with other OECD countries. For example, almost 15% of Denmark’s total tax revenue is made up of environmental taxes and these represent just over 4% of GDP. Across the Ditch, Australian environmental taxes are just over 2% of GDP, representing 8% of all taxation.

A recent OECD paper noted that in 2015, outside of road transport, 81% of emissions were untaxed. The report concluded tax rates were below the low-end estimate of climate costs (€30 per tonne of CO2) for 97% of emissions. New Zealand at €0.48 per tonne of CO2, was sixth from bottom of the 42 countries surveyed.

There would therefore appear to be significant opportunity for shifting some part of the tax burden onto environmental taxes. However, as both the Background Submissions Paper and the OECD notes many environmental taxes are “poorly designed and targeted.”

Wealth inequality and savings

The TWG’s terms of reference may have excluded taxing either capital gains from the family home or the land underneath the family home, but considering the taxation of savings is within its remit. So too is the issue of inequality and the Background Submissions Paper has a wealth (pun intended) of charts illustrating the issue of income and wealth inequality. (See Figures 12-19 between pages 33 and 38 of the report).

Ominously, the paper comments that over the past three decades the “inequality-reducing power of the tax and transfer system on market income inequality has steadily declined”. Furthermore, the inequality-reducing power of the tax-benefit system is now below the OECD average.

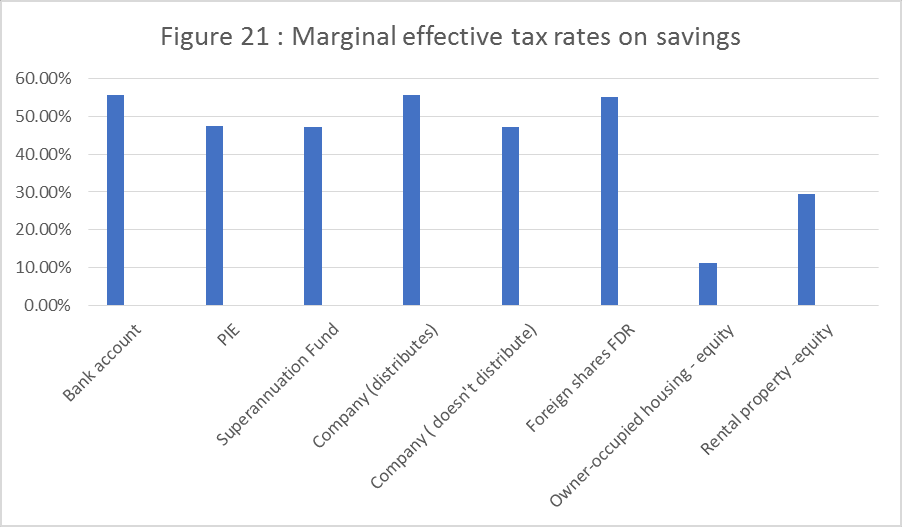

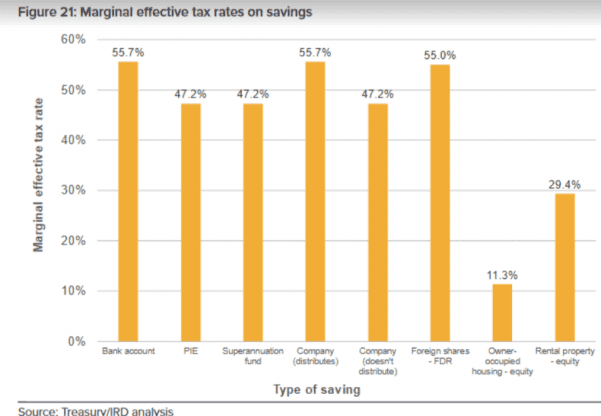

Tied into the issue of inequality is the taxation of household savings. It’s here that the impact of the terms of reference loom largest. After assuming a risk-free rate of return of 3%, inflation of 2% and a 33% tax rate to determine a marginal effective tax rate, the Background Submissions Paper then applied this to calculate the marginal effective tax rates of various asset classes. Its conclusion: “owner-occupied and rental housing is undertaxed relative to other assets.” The extent of the under-taxation is starkly illustrated by Figure 21 (reproduced below).

At 55.7% the marginal effective tax rate on bank savings is almost five times that of the 11.3% rate applicable for owner-occupied housing equity and nearly double the 29.4% rate for rental property.

The Reserve Bank estimated the value of housing as at 30 September 2017 to be over $1 trillion. Even excluding residential rental property (perhaps a third of the total), this is a huge amount of capital to be left essentially untaxed. The holders of that property are mostly older and wealthier, a growing number of which are receiving New Zealand Superannuation. As Andrew Coleman noted last year, changes to the tax system in the late 1980s established a huge incentive in favour of housing. This created an inter-generational timebomb which will need to be defused at some point.

Much of the immediate debate on the Background Submissions paper has been about the efficacy and impact of a capital gains tax, but there’s been little discussion about the ongoing fiscal impact of continuing to exclude maybe $700 billion of capital from taxation with potentially very adverse outcomes for future generations.

Overall the Submissions Background Paper includes plenty of thought-provoking material to consider. The paper also underlines what was apparent from the outset; excluding the taxation of the family home created a big hole at the heart of the review.

Whatever the final recommendations of the TWG are for addressing the future sustainability of the tax system there’s a danger it will be found as Macbeth warned after killing Duncan to “have scotched the snake, not killed it”. Only time will tell.