Progressive taxation on biological methane is John Lohrentz’s proposal to the New Zealand government as a tool to transition to a low carbon economy.

This week we look further into the importance of environmental taxation I raised last week, my first guest for this year is John Lohrentz, who works at the intersections of sustainability, social impact and tax policy.

John caught my attention because he was the runner up in the 2019 Tax Policy Charitable Trust Scholarship competition with a proposal on a progressive tax on biogenic methane emissions in the agricultural sector.

Transcript

Welcome, John. Thanks for joining us. So, what exactly are biogenic methane emissions and what is your proposal?

John Lohrentz

Yeah, well, I suppose the first thing I just want to say is thank you for having me. It’s great to be here. The discussion on environmental taxation is obviously something that I’m quite passionate about.

So, to give you a sense of what my proposal covers, I started from this thinking around the centrality of agriculture to our economy and to our way of life in New Zealand. And I started to look at what was happening over the next 10, 20, 30, 40 years.

There were a couple of trends that start to really stand out to me. One was that as the impact of climate change grows, it’s going to change the conditions for farmers. And those changing conditions are going to have impacts on how we farm and how we need to adapt our farming practices for our new world.

I also was looking at the fact that our population is going to grow by about 2 billion people globally in the next 30 years. This is going to create challenges with food security and at the same time as consumers are also demanding really new and different things. We’re seeing the rise of alternative proteins, of different milks and also a desire for better types of meat and better dairy products at the same time.

Looking at all of that, I start to just look at the agricultural sector and dairy in particular and what the future transition needs to look like. And I became quite convinced that actually really pushing ourselves towards more innovation in the agricultural sector is going to be key for the transition as we go into a low emissions economy and thinking about that.

I thought actually one of the ways in which we could quite effectively finance that move towards a more innovative agricultural sector is through a progressive tax on biological methane emissions. And basically, what my proposal is, is to look at the way in which instead of us taxing, in essence, the gross emissions of farmers at the farm gate, what we could look at doing is actually setting a tax that is built around the target.

What we do is over time, we reduce that target towards our 2030 goal and the Zero Carbon Act and our 2050 goal further on. And then the challenge for farmers is to keep up with that rate of change. And for farmers that meet or exceed that rate of change, there should be a net benefit to them. They should actually be getting money back through this proposal. And for those that are behind, a tax is applied progressively to recognise they’re actually at the further ends of the spectrum, where you can pick out the easy early emissions reductions.

And I think one of the big benefits from taking this approach is that we actually take this idea of being penalised for your emissions out of the equation. And the question is actually per either acre of land or per 10,000 litres of milk, the produce or whatever measure we want to develop, what is the level of emissions for that production? And this gives us a way forward of talking about the idea of actually maintaining or increasing production while we look at ways to de-carbonise how we do that.

TB

I mean, that’s what I find really compelling about your proposal. In essence it’s a behavioural tax. But it’s not a sort of a sin tax, like tobacco duties, etc. where the idea is to eliminate behaviours. Your proposal is to use tax as a tool to encourage a change, because like it or not, agriculture is incredibly important to the New Zealand economy and will remain so.

John Lohrentz

Absolutely, yes.

TB

And tax is a dirty word in this. But the key thing you’re doing here is picking up a theme that Sir Michael Cullen raised, and I was very intrigued by as listeners to the podcast will know. He talked repeatedly about the opportunity of using environmental taxation to recycle in and help move towards the lower emissions economy. That’s a key part of your proposal.

John Lohrentz

Yeah. I’m actually really glad you mentioned the Tax Working Group because obviously they had some things to say about environmental taxation. And I think one of the things that stood out to me from their report is that they built this framework for environmental taxation. They said these are the kind of things that we think an environmental tax would need to do in order to be a good idea, essentially.

One of the key things that they looked at is there kind of an elastic relationship between introducing this that’s going to have some behavioural sort of impact. And their analysis of emissions-based taxes is actually yes, there is some responsiveness there. This is a good area when we talk about greenhouse gas emissions to introduce taxation and then recycle the revenue back into the place where that’s coming from. The classic example might be something like a fuel tax in Auckland. The idea is if we’re taking the fuel tax out of Auckland, you put that money back into transport at the same time.

The other thing that I was quite interested in was the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment’s Report on farms, forests and fossil fuels, which came out last year.

TB

You cite that report quite substantially in your proposal.

John Lohrentz

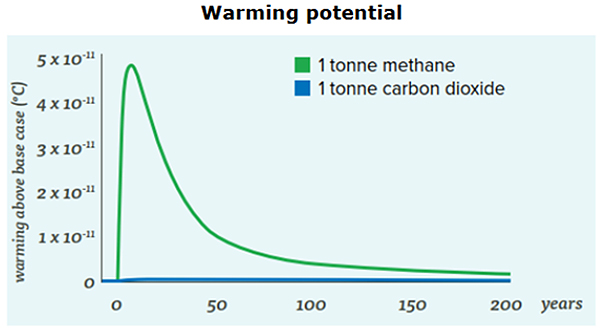

I really enjoyed it. And I think I think the reason it was quite gravitational for me is it was the first time I really clicked on the reality that we talk quite broadly about carbon or about greenhouse gases. But actually, there’s some real differences when we talk about methane as opposed to carbon dioxide as opposed to synthetic gases or nitrous oxide. And they all have different ways in which they impact on our climate.

Obviously, I’m not a climate scientist. I’m a tax interested person who is coming to an understanding of this. But in very general, in basic terms, a ton of methane that’s put into the atmosphere has a very, very strong impact initially. And then over time, that impact actually falls off as the gas is basically broken down in the atmosphere. Whereas if you emit carbon dioxide, the impact is lower initially, but it stays in the atmosphere for several hundred or even thousands of years.

When we start to think about how we design good policy, I actually think the beginning point for us is that we need to start with the science and have a really strong understanding of the different ways in which these gases are having an impact on our climate and then build back from that into actually thinking about the different ways in which we can approach these gases.

TB

And that’s actually one of the fundamental parts of your proposal, because what caught my eye when you’re looking at this, because people right away will say “Another tax! We’ve already got to deal with the emissions trading scheme!”

In your proposal, you’re saying take methane out of the emissions trading scheme and deal with it separately because of the science behind it. Do you want to talk a little bit more why you think that change in the ETS is important in this regard?

John Lohrentz

Yeah, I mean, first of all, I think it’s really important for me to say that I’m really happy to see the work being done on the emissions trading scheme. And also, I in no way consider myself an expert on it. But when we talk about interventions, when it comes to reducing emissions, the two broad ideas either are creating a price mechanism or this kind of cap and trade system, which is the emissions trading scheme.

And there are some real benefits from the emissions trading scheme if it’s done really, really well, which is if you include all the industries, all the types of gases, then you can kind of get to this point where you have a working market, to speak, for emissions. The problem is, is that if you have that one price, single price, there’s a risk that we actually distort the decisions we’re making about where we put the most of our energy in reducing emissions, recognizing that difference in the profile of different gases.

This idea that action in different ways is all substitutable so reducing a tonne of carbon is the same as reducing certain amount of methane I think is problematic. And Simon Upton the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment points that out.

Some of the proposals that have come out from the Interim Climate Change Committee,

Ministry for the Environment and also some of the work done by the Productivity Commission earlier last year has looked at this. They said, well, there are definitely some pros and cons to running with the emissions trading scheme and building on what we already have or looking at the opportunity to introduce a tax or levy. And the Interim Climate Change Committee actually recommended let’s go to Malta was a levy when it comes to methane emissions from agriculture, because the profile of it is really different. And it’s also really important for us to recognize the centrality and the primacy of agriculture in our economy.

TB

Just on that a levy would not gone down well with farmers straight away. And so what you’ve gone said, well, let’s go and look at methane. And there’s two parts to it as I mentioned earlier. There is a tax on emitters of methane above a certain threshold. But more importantly, you propose recycling the tax through Research and Development tax credits.

John Lohrentz

Absolutely. And if I if I was to try and articulate how I would actually talk about my policy to people, I think I would start by saying this is a focus on innovation. And I think the tax mechanism, as useful as a way of talking about how we raise revenue to support that in a potentially innovative and effective way. But really the central focus of what I’m proposing is a 40% targeted tax credit for R&D in the agricultural space.

I did some work with numbers from Treasury and other places to kind of get a sense of how we can make this work. And it looks like one way we could do this is we could use the tax revenues we collect and split them reasonably equally between this R&D tax credit, but also a refundable tax credit to farmers who are below that threshold I talked about earlier.

The idea would be for farmers who are really pushing to operate sustainably instead of having a tax payment because they still have some gross emissions, the fact that they’ve done work and really put some effort in is recognized and is actually a value that they receive back as a refundable tax credit. And then at the same time, we’re stimulating some of the technological advancements we need to really reduce emissions, which should accelerate the whole journey of the industry.

TB

And this is something that’s been talked about, the wider perspective by Fonterra and other is that if we can innovate in this space, the global potential is enormous, absolutely enormous, particularly because of the methane emissions. So, yes, that’s another reason I found it’s an extremely interesting proposal.

John Lohrentz

Can I talk to that a little bit more? One that one thing I’ve been reflecting on in preparing for our discussion today is the Tax Policy Charitable Trust scholarship competition.

Immediately following [the announcement of the finalists] the next day I was in Wellington and it was about a week after the Zero Carbon Act had been passed. I was just walking on the waterfront and quite a large group of people who were gathering ready to walk to Parliament for a protest. And it became quite evident quite quickly that this was a group of farmers that had come from all over the region and wanted to deliver their message to some of the some of the ministers. And I had the opportunity to walk and talk with some of them.

TB

Your report is full of little insights in there, which should encourage everyone to think about farming. For example, the current level of indebtedness in the farm sector. What is it? 35 per cent of farmers have a debt to income ratio per kilo of milk solids that’s more than five to one?

John Lohrentz

It’s about $35 of debt for every kilo of milk solids. And they may have changed since I wrote my proposal. But I think what it goes to illustrate the fact that over a third of farmers are living with that really high debt is a real strain. And that number specifically is with the dairy industry. I think what that indicates to us is that there are some people who are doing really hard work. And the problem with that debt is that at the end of the day, there’s a lot of other factors that can impact on the milk price. As it is you can do a huge amount of work and then barely breakeven even in a good year.

If we bring an integrated lens as to how we think about that journey towards sustainability, is we also have to be really thinking about the well-being of our farmers through this transition and all of the financial factors that actually go into making that sector successful. I think there’s a lot of really good stuff happening, and we just need to carry on and be really clear as to how we how we have this conversation together.

TB

Yes, I quite agree. We were talking off-air about this risk of the town versus country divide you hear about. And one of the things I think that makes what you’re proposing interesting and compelling is it addresses those issues because it encourages behaviour. It’s not ‘You’re naughty, you must reduce that’. You’re saying those who move along this path to lower emissions will get refundable tax credits and the innovators will get rewarded.

And that then points the whole industry away from this volume-based model. As I mentioned, with a debt of $35 per kilo of milk solids and the price at seven dollars, the ratio is five to one. But if the milk solids price goes down to six dollars, suddenly that ratio six or seven to one. It’s a hell of a risk to carry. And the banking sector, as farmers well know, is starting to draw back from lending to the dairy sector. Sale prices for dairy farms are flat as well. So, there’s a number of pressures coming on for the sector.

John Lohrentz

I think one of the pieces which is really point for me to acknowledge is I think our long-term future remains as an agricultural nation. I mean, especially when we think about the success of our regions, farmers are really integral to that. And I think that there’s this really incredible opportunity with how demand is shifting, especially overseas, to really champion the cause of highly sustainable agricultural products in all their forms.

TB

I couldn’t agree more. On transition you talked about 2030 as a target, but you are saying that about 30% of farmers are already meeting your proposal’s targets.

John Lohrentz

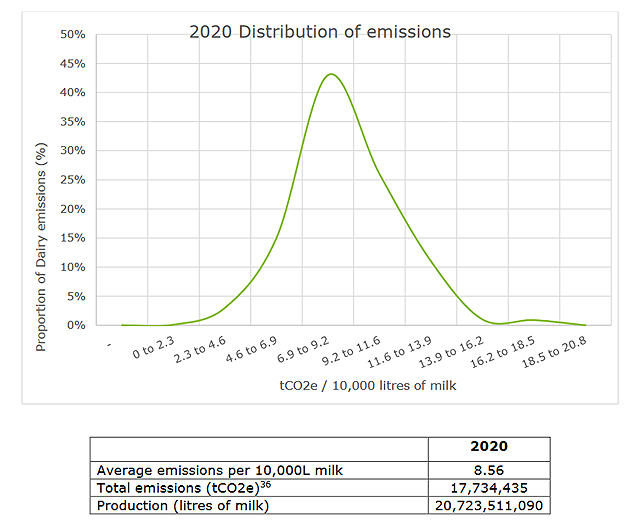

These are my estimates so they’re not perfect. I think there’s definitely some more work to be done to understand how this is looking. But just taking the dairy industry, for example, the kind of spread of emissions per 10,000 litres of milk produced at the farm gate basically follows a normal distribution, but with a little bit of a fat tail towards the heavier emitting side. I looked at this and the targets we’ve set ourselves as a nation now through the Zero Carbon Act.

And actually, as of when I wrote my proposal, about 14 per cent of farmers are already below the rate that we want to achieve by 2030. And so, it’s a move to try to move towards achieving our target, which is about 10 per cent reduction in methane emissions by 2030.

What it would look like is about half the farmers in the sector activating quite strongly so we move from about 14 per cent below that threshold to about a third of farmers, definitely below their threshold with a heavier tail kind of moving more into the mid-range. And I think that’s entirely achievable.

When the Biological Emissions Reference Group reported in 2018 they said that based on a lot of the technologies and practices we already have in terms of best practice for how to run a farm they believed it was possible to get that 10% reduction even if we don’t see some of the technological breakthroughs that we’re hoping to see in the next 10 to 20 years. So, even if a methane inhibitor or a vaccine is not developed, we can still definitely get to our 10% target reduction. But the reason I think we need to invest in innovation now is because that’s what’s going to give us the ability to unlock our success towards 2050 on a longer timeframe.

TB

And these are long run investment projects, to be quite frank. You mentioned the work the Tax Working Group did in outlining a framework we need to work on. What other environmental taxes do you think we could be seeing coming along following that framework?

John Lohrentz

That’s a great question. The Tax Working Group’s looked at obviously emissions as we’ve already talked about. And that was both from the perspective of a potential tax, but also the emissions trading scheme. They also looked at some of the existing environmental taxes we have, which are around solid waste such as the waste disposal levy. They looked at water abstraction and water pollution and then they also looked at congestion taxes. Then they started to foray a little bit into more novel taxes. There was some discussion around this idea of an environmental footprint tax or a natural capital enhancement tax. Leaving those last two aside, I do think that there is some potential work to be done in that space of taxes on water abstraction/pollution, solid waste and congestion as well.

These are all really interesting issues. But at the same time there is a confluence of potential environmental impacts, financial impacts and also social impacts from all of the decisions we make around that. And one of the things I appreciated about how the Tax Working Group approached this question of environmental taxes is that they were very clear that our goals in the short and medium term should be quite different from our goals in the long term.

Looking long term, what we need to be focussed on is actually how do we build up a new framework of environmental taxation that could be a stronger base for our economy and that could potentially take some of the pressure off other areas like, for example, income tax.

And that’s going to take some serious work because we don’t just need a framework. We need a whole new way of thinking of how we structure the design for how we do this well to ensure that it has equity both in the temporal sense and also a distributional sense. I think that’s the big work to be done. And we can definitely start that now. But it’s going to take time to build that framework out in the shorter term.

How the Tax Working Group thought about environmental taxation largely focussed on this idea of internalizing negative externalities. I think that there’s definitely some work to be done there to ensure that where potential environmental damage is occurring through pollution or water abstraction or other avenues, that there is more focus put on ensuring that people who are doing that are paying for that.

However, I think we need to move quite slowly and also recognize that our thinking on what natural capital is and how to best protect that is just evolving. There’s more work to be done to actually develop that theoretical base for how we approach this. We shouldn’t just kind of gung-ho go ahead into establishing all these new taxes. I mean, the reality is, is right now environmental taxation revenue is about 6.2% of the Government’s budget. And I definitely think that can go up. But the way in which we do that and think about the kind of counterbalancing that we do at the same time is very, very important.

TB

On environmental tax the OECD recently released a report on taxation of energy, which in fact was highly critical of just about every country for their approach to taxing energy and the inefficiencies from that. What’s your thoughts on the OECD approach?

John Lohrentz

Obviously energy is really central to our progression towards a low emissions economy. The idea of where do we actually get our energy from matters because everything we do uses energy in different forms. I think we’re doing quite well in New Zealand with at least 80% or 85% renewable for a lot of our sources, especially around Wellington where I think it’s close to 100% renewable now.

I think some of the challenges that are going to be really central for us over the coming couple of decades are going to be first of all focussed around different industries. I’ve chosen to focus on agriculture because I think it merits the time to spend a lot of our energy thinking about how the sector engages. I think also transport is going to be very interesting and I think forestry will be the element where there’s some real important conversations we need to have around what role forestry plays in our transition.

TB

Yeah, you mentioned forestry in your proposal, because just to pick up a point you mentioned earlier, one of risks about the ETS is we could be busily reforesting areas because that gives a good initial short term answer in terms of meeting emissions targets. But longer term that may not be the most efficient use of the land.

John Lohrentz

This is also coming from the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment’s report where there are some really interesting discussion going on about the expectations we have around the usefulness of tree planting. And the key thing that the Commissioner said essentially was we don’t want to get to a point in 2050 where essentially what we’ve done is scored a net accounting victory. We’ve got to near zero, but we actually haven’t done that really hard work to really decarbonise the emissions in our economy.

And just to be clear, I’m a gardener, I love gardening. I love things that grow. And from that, I have a very strong preference for this idea that we should be planting. We should be going for it. Native trees everywhere, just plant, plant, grow, let things reforest and go for it. I think the bigger challenge is looking at the whole picture and saying we can’t just pay for our sins and carry on committing them.

There’s this need for all of us to be responsible for playing our part, whether at the business level, economic level or personal level to reducing some of those emissions.

TB

I couldn’t agree more. And what I liked about your proposal is it encourages change, encourages focus on the issue. It encourages innovation, which for an agricultural economy like New Zealand represents a huge opportunity. This is a classic case of looking at an issue and turning the telescope around to say, “OK, there’s an opportunity here for us. How do we manage that transition?” I commend John’s paper to you all.

I think that’s a really good place to leave it there. John, thank you for joining us.

John Lohrentz

Fantastic, thanks for the opportunity to have a discussion. I’m looking forward to more in the future.

TB

Me, too. This will no doubt be the first of many environmental discussions that we’ll be having over the coming decade.

Well, that’s it for the week in tax. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time have a great week. Ka kite āno.