The UK’s Spring Budget drops a big change which will affect tens of thousands of Kiwis and British expats with the end of the remittance based taxation regime.

- More on UK trust filings, and why are there so many trusts in New Zealand?

- Financing local government, time for change?

I’ll be honest, even after 30 years in New Zealand, I miss British budgets. There’s a building sense of anticipation beforehand, as rumours circulate about bold tax plans and the abolition/introduction of new measures. Then on the day itself, we have to deal with the myriad of tax measures introduced, usually always without any warning beforehand, other than leaks to selected media. Being perfectly cynical, they are handy work-creation events, much more so than their New Zealand counterparts. (That said this year’s May Budget here is looking like it will be the exception, which proves the rule).

This year’s UK Spring Budget, which was released on Wednesday night, did not disappoint. There were a whole raft of measures, some of which, to borrow the phrase the 1974 Lions adopted in South Africa against the Springboks involved “Getting your retaliation in first”. These measures were done simply to hamper what’s expected to be the next Labour government after Britain has its General Election sometime this year.

Ending the Remittance Basis of taxation

So, there’s a lot to consider, but there were two that are of particular interest to New Zealanders, and these are to do with the so-called non-dom rules. The UK has a special set of rules called The Remittance Basis of Taxation for non-domiciled persons. That is people, generally speaking, born outside the UK, and they are able to basically exempt their non-UK sourced income from UK taxation, if they don’t remit it to the UK.

These rules have been around for a long time and there has been a lot of amendments in recent years. And I suspect there is a fair bit of non-compliance going on from people here in New Zealand, who’ve not kept up with those changes.

The UK Labour Party had indicated it would remove the regime as a fundraising measure. Instead, the Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, (Finance Minister), Jeremy Hunt, has gone ahead and decided to pre-empt that by abolishing the regime with effect from 6th April 2025. It will be replaced by a regime which looks very similar to the transitional residence exemption we have here. That is, individuals will not pay UK tax on foreign income and capital gains for the first four years of UK tax residence.

There will be some transitional rules which will apply to existing individuals who are claiming the remittance basis. You can claim remittance basis for up to 15 years, but after a period of ten years you have to start paying a Remittance Basis Charge of £50,000. And then after 15 years of tax residency in the UK, you’re deemed to be domiciled in the UK and the exemption no longer applies. It’s long been a very controversial measure. The wife of the present Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, is apparently a non-dom and questions have always been asked about whether she made use of that exemption as she comes from an incredibly wealthy family.

I’ve got a number of clients moving across to the UK, or who are all already there, and we’re looking at the question of how to manage the implications of becoming UK tax residents. So, this proposal is interesting to see. More details will emerge, obviously over time, but it is significant in that it will perhaps make it a little easier for people to migrate to the UK without triggering huge tax liabilities or having to manage them extremely carefully under the remittance basis regime.

Domicile and Inheritance Tax – good news for Kiwis & UK migrants?

Related to the end of the remittance basis regime and arguably even more important, are changes to the UK’s Inheritance Tax (IHT) regime. IHT is a unified estate and gift duties, and probably should be still what it was originally called Capital Transfer Tax. At present, IHT applies to all assets situated in the UK or all assets worldwide if the person is domiciled in the UK.

The proposal is that those current rules will also be replaced from 6th April 2025 with a residency-based set of rules which will probably involve a ten-year exemption period for new arrivals and then a ten-year tail provision for those who leave the UK and become non-resident. What that tail provision may mean is that someone who’s been resident or domiciled meets the test for IHT, may have to be non-resident for ten years to escape the full effect of it.

Now, in my experience, the impact of IHT on Kiwis who’ve been over in the UK or have assets in the UK, and then Brits like myself, who’ve migrated here, is not very well understood. But as the Baby Boomer and older generations are starting to pass away now, there’s a great transfer of wealth going on. The amount of IHT that the UK government is collecting is steadily rising. It’s now up to over £7 billion a year (0.3% of GDP, about $1.2 billion in New Zealand terms), steadily heading towards 0.5% of GDP. So, it’s starting to become a more significant part of the tax take.

These new rules may mean that people who have previously been caught in the regime will be out of it, but it may also mean that people who thought they were outside the regime may be caught. There’s no indication here that the rates that apply – 40% on estates worth more than £325,000 pounds or $650,000 thereabouts – have been changed. It’s a tax that people feel needs reform in that there is plenty of scope for mitigating it. It falls very heavily on relatively smaller states rather than the larger estates where they have the wealth to do some more estate planning.

More tax breaks for the film industry – a lesson for the Government?

And incidentally, just before moving on, I notice this budget also contains a number of measures to promote the UK film industry and theatre as well as the arts. These will provide over £1 billion in additional tax relief over the next five years. One of the things that’s common amongst tax systems around the world is support for the film industry, and the film industry as a whole is pretty cynical about going to where the best incentives are.

I think it’d be interesting to see just how the Coalition Government responds in the May budget about pressures mounting on the Screen Production Rebate, whether that’s going to continue in its present form. The industry here will be lobbying for it to continue because although we can’t compete with more generous exemptions that may be provided elsewhere, the rebate still provides the skills that have been built up here thanks to the likes of Weta Workshop and others which makes New Zealand skills still highly sought after. The Screen Production Rebate is the little kicker which helps get the deals across the line.

More on UK trust statistics and a warning about the perils of overseas trustees

Larger estates in the UK will undertake a fair amount of mitigation to minimise the impact of Inheritance Tax, and that invariably tends to involve the use of offshore trusts. I mentioned in last week’s podcast the extraordinary fact that in absolute terms more tax returns are filed in New Zealand for trusts than in the UK.

This provoked a lively debate in the comments section with some pointing out the UK numbers don’t really reflect trusts that have been set up to go offshore into tax havens such as the Caymans and the Isle of Man. Well yes, that’s right, the UK numbers don’t reflect this because trusts’ tax returns, for UK purposes are generally required to file tax returns based on the residency of the trustees.

That by the way, is a matter people here need to pay more attention to. If a beneficiary or trustee migrates to the UK, this may inadvertently make a New Zealand trust with New Zealand assets subject to UK taxation. Again, this is another matter which isn’t well understood, and I suspect there’s a fair bit of noncompliance going on.

The UK also has a Trusts Registration Service. This was in response to the EU’s Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive from 2017, which the UK went ahead and implemented despite Brexit. The UK actually went in for a tighter regime than the EU had proposed. According to the same statistics that the HMRC held about trust tax return filings in the UK, the Trust Registration Service had 633,000 trusts and estates registered as of 31st March 2023 and which remain open as of 31st August 2023. This includes 462,000 new registrations in the 12-months to 31st March.

This surge in registrations is the result of a compliance effort by HMRC to remind people around the world that if any trust has a property in the UK, or even has made loans to beneficiaries in the UK, it may have a UK tax liability, and therefore should register under the Tax Trust Registration Service. This is regardless of where the trustees are tax resident. And again, I suspect there is a fair bit of non-compliance here.

Why are there so many trusts in New Zealand?

But even if you take these greater numbers, we’re still left with the rather astonishing fact that per capita large number of trusts in New Zealand relative to the population. How did that evolve was one of the questions asked in the comments. The short answer would be that the effective abolition of Estate Duty in late 1992 removed the impediments to setting up trusts. What we saw in response was something quite unusual in trust law, where it was now quite possible for a single person to be the settlor (or the person who settles property on the trust), a trustee responsible for managing the property, and a beneficiary. This is very unusual in trust law terms around the world.

I think it has to be said that some lawyers and other practitioners took advantage of that opportunity to market themselves and trusts extremely well. Back in the early 1990s, by putting assets in trusts it was possible to mitigate against the impact of rest home charges. The income of trusts was not then taken into account when determining eligibility for the likes of Working for Families or student allowances.

All that has changed over time and my view is that a substantial number of the estimated 500,000 trusts that we have in New Zealand are no longer necessary. That’s also the view of many other practitioners in this space. So it will be interesting to see what happens over time as people realise the complexities of using trusts and the inadvertent tax issues that are created when trustees, beneficiaries or settlors move to another jurisdiction.

Since the start of the year, I’ve seen an upsurge in requests for advice in relation to trustees, beneficiaries or settlers moving to the UK or making distributions to the UK.

I don’t expect that to slow down, and I think it’s actually the tip of the iceberg.

Beware the information exchanges

I would also add that probably because of the common reporting standards and the automatic exchange of information as various tax authorities work their way through all that information that’s being accumulated and distributed around the world, they will be realising that they many trusts are non-compliant, accidentally or not, and they’ll be starting to crack down on it.

Local government finances, time for reform?

Finally this week, local governments are now looking to set their rates for the forthcoming 2024-25 year. The fact that no replacement for Three Waters has been found and the substantial infrastructure deficit we as a country have allowed to develop, means that rates are likely to be rising quite significantly for many of us. That’s obviously going to generate some pushback.

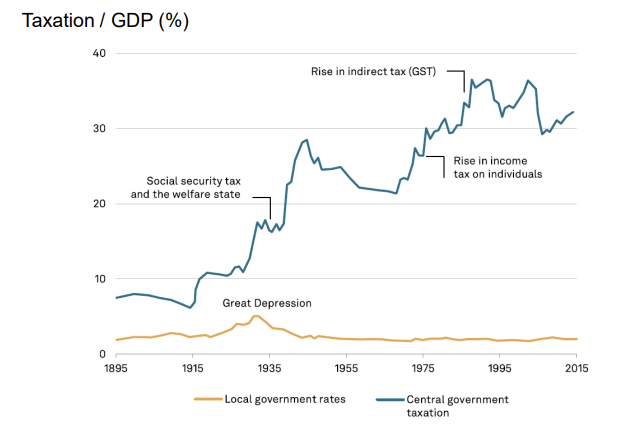

Writing on this topic Dan Brunskill noted the quite astonishing stat that local government rates have basically not increased as a percentage of the economy in the past hundred years.

Basically, local rates have stuck around about 2% of GDP overall across the country about $8 billion in rates are paid. (Not all that you pay to a Council is actually rates based on property values, there’s also the Uniform Annual General Charge together with the various services such as consent fees that councils charge).

As the graph illustrates, apart from the spike around the Great Depression period, when councils and central governments all did more to try and help alleviate the impact of that, rates as a percentage of GDP have been stable for well-nigh 90 years. I think the present rating present funding of councils is unsustainable, because, as the article notes, central governments keep giving local governments more and more to do, but restrict them in the level of income that they can raise. That’s both good and bad. We don’t want what happened with Kaipara District Council, which essentially went bankrupt because it could not fund a wastewater system in Mangawhai.

There’s scope for reform in this space. I think the crunch points around finance are arriving now and local and central government will need to think harder about how local government can be funded and what funding mechanisms are appropriate. For small councils such as Kaipara or, Waiora over near Tairawhiti East Coast, the funding issues and scope for raising funds are not the same as for Auckland a council with a rating base of over a trillion dollars. The laws need to change in my view, but we’ll have to wait and see developments.

As always, we will bring those to you when they happen. And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.