Inland Revenue guidance on the tax implications of the Clean Car Discount

- Inland Revenue guidance on the tax implications of the Clean Car Discount

- Latest on Inland Revenue’s audit activity

- Insights from the OECD’s latest report on Corporate Tax Statistics

Transcript

In the week that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report declared that climate change is “unequivocally caused by human activities” it is rather opportune of Inland Revenue to release its guidance on the tax implications of the Government’s Clean Car Discount Scheme.

To recap, the Clean Car Discount Scheme has been introduced to make it more affordable to buy low emission vehicles. Between 1st July 2021 and 31st December 2021, a rebate will be paid to the first registered person of an eligible vehicle or to a lessor where that person is a lessee.

Starting 1st January 2022, it’s proposed that the Clean Car Discount will be based on vehicle’s CO2 emissions and vehicles with low or zero or low emissions will qualify for a rebate and those with high emissions will incur a fee (subject to enactment of the relevant legislation).

Now obviously, if you’re in business, you need to be aware of the tax consequences if you receive a rebate or pay a fee under the Clean Car Discount Scheme, or lease a vehicle that comes under the Clean Car Discount Scheme. And obviously the outcome varies depending on what you use a vehicle for.

If you get a rebate under the scheme, you will not have to pay income tax on the rebate. It’ll either be treated as excluded income under the rules for government grants if you’re claiming depreciation on the vehicle or a capital receipt. Conversely, if a fee is paid under the Clean Car Discount Scheme, it will be treated as a capital expense and so no deduction will be available. And that’s obviously going to be something which should be watched carefully.

Now, if you’re using the vehicle in your business, and seeking to claim depreciation, then the base cost for these purposes will be either reduced by any rebate received or increased by the amount of any fee. That’s again something to watch out for.

When it comes on to FBT, and this is going to be quite critical, I would say given that we suspect there’s a fair bit of under compliance in this area, FBT will be payable if the car is made available for private use. FBT will be calculated on the cost of the car when purchased or its value if being leased. The cost will either be reduced by the amount of any rebate or increased by the amount of any fee.

For GST purposes, if you get a rebate under the Clean Car Discount Scheme for a vehicle that you use in your taxable activity, the rebate will be treated as consideration for a deemed supply under the rules relating to government grants. So that means you must the return the GST in your next GST return. Conversely, if a fee is payable, then the GST component of that may be claimed as input tax if you’re carrying on a taxable activity.

Overall, this guidance is useful. Inland Revenue have included some examples as well. As I said, it is quite opportune that it arrived at this time when there’s going to be increasing focus on the question of environmental taxation and the role it may have in enabling us to meet our targets under the Paris Accords.

Tracking Inland Revenue audit activity

Moving on, as I mentioned just now there is a suspicion that there’s perhaps non-compliance with FBT going on at the moment. And so it’s quite interesting to see the latest statistics on Inland Revenue audit activity from Accountancy Insurance.

This is the company that provides insurance against Inland Revenue audits and reviews.

For the period to 31 March 2021, they saw the total number of claims increased by 31% compared with the year ended 31 March 2020. So even though it was in the middle of a pandemic, Inland Revenue is still active in reviewing taxpayers. What is interesting to note here is that GST verification claim activity increased by 48% and that for income tax return related activity increased by 67% over the 12 months to 31 March 2021.

Now, this apparently includes two projects Inland Revenue began last year, the bright-line property rules and also the automatic exchange of financial account information programme relating to the Common Reporting Standards.

GST verification activity actually accounted for 90% or more of all claim values in New Zealand, even though actually only 55% of all claims related to GST verification. So that’s a timely reminder that Inland Revenue is still keeping a watchful eye on matters.

It’s actually a little encouraging to hear that Inland Revenue is still actively reviewing GST returns. I’ve seen one or two instances where I’ve wondered how claims got through including one warranty case going on right now where I am really surprised why Inland Revenue was not onto what was happening much, much sooner.

But the fact is, despite the pandemic and the impact it had on general operations for Inland Revenue last year, GST activity has still been maintained. You have been warned

Interntional benchmarking

The OECD recently released its third edition of its corporate tax statistics. It’s a treasure trove of information relating to corporate tax around the world and with the topics covered and statistics reported being steadily expanded. And there’s some very interesting insights in the report which is based on 2018 numbers.

Interestingly, that the percentage of corporate tax revenues has risen since 2000 from an average of 12.3% then to 15.3% in 2018. Similarly, you see a rise in the average corporate tax revenues as a percentage of GDP from 2.7% in the year 2000 to an average of 3.2% in 2018. New Zealand by the by at 5.2%. is well above that average for 2018.

This is an interesting statistic because over that same time period since 2000, the average statutory tax rate has fallen by 8.3 percentage points from 28.3% in year 2000 to 20% in the year 2021. Over that time the rate has fallen in 94 jurisdictions, stayed the same in another 13, but increased in only four jurisdictions. And that supports the argument that was made that lowering the statutory tax rate and broadening the base would lead to higher revenues.

I do think that we probably now plateaued out with tax cuts. I don’t see corporate tax rates continuing to fall. Over in the United States, they’ve signaled that they will rise.

The report drills down into the statistics by considering effective marginal tax rates as well. And that’s where it gets interesting from New Zealand’s perspective, again, because we adopted more thoroughly than most and the broad-based low-rate approach to corporate taxation by stripping away a lot of preferential regimes, our effective marginal tax rate is at just over 20% is amongst the highest in the OECD. Apparently, that is because we have less general fiscal depreciation rules than other most other jurisdictions, although the report notes that we are now more generous after increasing rates in 2020 in the wake of the arrival of the pandemic.

The report also has details of the impact of the implementation of BEPS and statistics relating to anonymised and aggregated country by country reporting although New Zealand doesn’t feature in this part of the report.

But it also has something that I think policymakers here would want to perhaps think hard on, and that is the question of tax incentives for research and development.

What the report notes is that R&D tax incentives are increasingly used to promote business, with 33 of the 37 OECD jurisdictions offering tax relief and R&D expenditure in 2020, compared with just 20 in 2000. New Zealand is one of those countries now doing that.

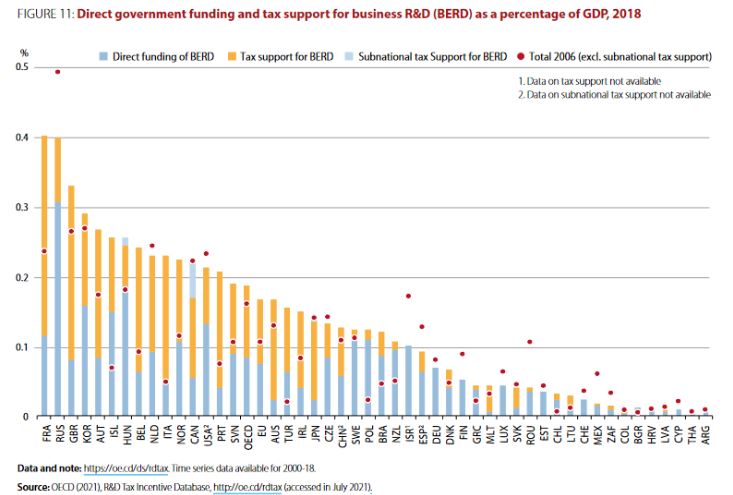

And perhaps we need to think very hard about that because in the statistics showing what the direct government funding and tax support for business R&D as a percentage of GDP in 2018, New Zealand is way down the list at just over 0.1% of GDP. You see countries like France and Russia at 0.4% and the United Kingdom, Korea and Israel close to 0.3%.

So we are way off the pace here. And it has been noted for some time that we do not invest enough in R&D. It was one of the reasons the R&D tax incentive scheme was introduced. So, as I said, there’s plenty to consider in this report with heaps of detailed appendices that you can trawl through.

Robin Oliver tax policy scholarships

And talking about tax policy, this week the Tax Policy Charitable Trust announced its annual Robin Oliver tax policy scholarships worth $5,000 for students majoring in tax at either Victoria University of Wellington or at the University of Auckland.

And later this year the Tax policy Charitable Trust will be launching its 2021 competition scholarship competition for tax policies. You may recall that we had the 2019 winner, Nigel Jemson, as well as one of the runner ups John Lohrentz on the podcast. I’m looking forward to seeing what comes out of these policy submissions in due course.

Well, that’s about it for this week. But before I go, it so happens that it is now 17 years since Baucher Consulting started. And as some of you may know, we recently undertook a slight reorganisation carving out some of our compliance functions to Agentro Limited. Big step that, it’s been a great journey for the last 17 years. And I’m looking forward to the future.

I’d just like to take this opportunity to thank my colleagues Eric, Darryn and Judith for helping me get here together with all our clients and many well-wishers who responded to our latest newsletter covering this news. Thank you very much. We really couldn’t have done it without you.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening. And please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next week, ka kite āno.