23 Mar, 2020 | The Week in Tax

- Depreciation on buildings restored

- Low value asset write-off limit increased to $5,000

- Residual income tax threshold raised to $5,000

- Inland Revenue to have discretion to write off use of money interest

Transcript

The Government has released details of its COVID-19 support package and I’m here to discuss the four specific tax measures which form part of that response.

These measures are a mixture of giving immediate relief to taxpayers, who are going to be feeling the pain right now. They are also hoping to encourage investment activity going forward as the eventual recovery takes place.

There were a few surprises in this with the big surprise being the reintroduction of depreciation on commercial and industrial buildings. And this includes hotels and motels. So clearly this is of interest to a sector, the tourism sector, which is going to take a very significant hit as this COVID-19 pandemic continues.

The proposal is that depreciation will be reinstated for those buildings, and a diminishing value rate of 2% is proposed. (They’re working on the straight-line rate and hadn’t yet finished the actuarial calculations on this).

And quite apart from this welcome measure for industrial buildings it also means the capital cost of seismic strengthening will now be depreciable. This has been a sore point for many building owners for quite some time. And in my view, it is a matter that it should have been addressed some time ago.

But leaving that aside, it is an incredibly welcome move to see the depreciation restored in general for commercial industrial buildings and acknowledging that this would include the capital cost of seismic strengthening. It’s worth noting as well that this was one of the recommendations of the Tax Working Group. They suggested that they couldn’t really see any valid reason to continue the policy adopted in 2011 of stopping depreciation on industrial and commercial buildings.

Looking back on the papers from that 2011 Budget, the impression I gained was that that measure was one which was designed to actually balance the books and wasn’t really driven by anything around the fact that there was no economic depreciation going on. Quite clearly buildings depreciate and need replacing. That was true then and it’s true now so it’s simply great to see such a measure.

It’s an expensive measure, estimated to cost $2.1 billion over the forecast period to the 2023/24 fiscal year. I know from business owners and those with property investments in this sector that this will be very, very welcome. The legislation will obviously be rushed through shortly and it is intended to take effect from the start of the 2020/21 tax year, which for most people is April 1.

Also extremely welcome for taxpayers is the proposal to increase the low value asset 100% write off. This is something the small business sector has frequently requested.

This measure contained a surprise in that the level will be increased from $500 to $5,000 for the 2020/21 tax year before falling back to a new increased level of $1,000 with effect from the start of the 2021/22 income year and going forward.

The current $500 threshold has been in place since 2005 if memory serves right. So it was long overdue for an increase. The one-off increase to $5,000 follows a measure the Australians did a couple of years back. This is again extremely welcome. It will encourage investment, but it also greatly simplifies small businesses’ compliance costs.

The measure is estimated over a four-year period to cost $667 million. That’s not as much as I had thought, given that Inland Revenue and Treasury had been previously reluctant to increase the threshold. Again, a very welcome measure. The $5,000 is a bit of a surprise, but again, it’s a good opportunity for businesses once they come through what is going to be frankly, a pretty rough few months. No one’s sugarcoating that but looking ahead they may take the opportunity to upgrade their equipment and invest in new plant and machinery.

Small businesses and individual contractors and the like will welcome the decision to increase the provisional residual income tax threshold from $2,500 to $5,000. And that means with effect from the 2020/21 tax year that basically enables those taxpayers who meet that threshold will be able to defer paying their tax for the coming tax year to basically February 7, 2022.

So that immediately gives some cash flow relief for the micro businesses that are going to be really affected by what’s happening around us right now. The estimated cost of that is about $350 million. But it is a more a deferral because it means the tax is going to be paid later than previously anticipated.

The final specific tax related measure gives the Commissioner of Inland Revenue discretion to write off and waive interest on late tax payments for taxpayers who’ve had the ability to pay tax “adversely affected” by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Now the use of money interest rate is currently 8.35% and surprisingly, no announcement was made about reducing that rate. I think officials were of the view that that can wait till the regular review, which must happen now in the wake of the OCR cut we had on Monday. So, we probably will see very shortly the use of money interest rate on unpaid tax come down and that will be of help to taxpayers as well.

This is actually applicable from February 14 and it covers all tax payments, which includes provisional tax, PAYE and GST due on or after that date. Taxpayers who are struggling to meet those payments will be able to apply to Inland Revenue and say, ‘we are struggling here as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak’. The requirement is for a “significant” fall which is defined as approximately 30%.

This initiative is going to last for two years from the date of enactment of the announcement unless it’s extended by an Order in Council. So that’s good news. I’ve already had a few inquiries from clients about what do we do when we’re struggling to meet payments. And this is a very welcome relief.

Incidentally, although not specifically mentioned in the announcements, by implication, the late payment penalties and late filing penalties are already going to be suspended as part of this measure to help businesses. Again, a good measure. My longstanding view is that the late payments system does not work and should just simply be scrapped. Hopefully we’ll see something major on this later this year. For the immediate time, suspending use of money interest is a very welcome step.

Just briefly on the other announcements, obviously the leave and self-isolation support and the wage subsidy schemes for small businesses, are going to be very welcome. These schemes apply to independent contractors, so that’s going to be a great deal of relief and take off some of the pressure for them. And for all small businesses, we’ll be looking at the question of what do we do about self-isolation if key staff were taken out of work. This will help considerably.

Interesting point which has also happened and has gone a bit under the radar, is that for working for families, there is an in-work tax credit, which is a means tested cash payment of $72.50 per week. This was only available to families that who are normally working at least 20 hours a week if they were sole parents, or 30 hours a week if couples. The hours test has now been removed, so about 19,000 low income families are going to benefit from that change. And I know the advocates of Child Poverty Action Group, they’re very pleased at what’s in this package with the help for low income families and beneficiaries.

I’ll have more on this week’s tax events with my regular podcast on Friday. But in the meantime, that’s it for this special edition of the Week in Tax.

I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next Friday have a great week. Ka kite āno.

3 Feb, 2020 | The Week in Tax

Progressive taxation on biological methane is John Lohrentz’s proposal to the New Zealand government as a tool to transition to a low carbon economy.

This week we look further into the importance of environmental taxation I raised last week, my first guest for this year is John Lohrentz, who works at the intersections of sustainability, social impact and tax policy.

John caught my attention because he was the runner up in the 2019 Tax Policy Charitable Trust Scholarship competition with a proposal on a progressive tax on biogenic methane emissions in the agricultural sector.

Transcript

Welcome, John. Thanks for joining us. So, what exactly are biogenic methane emissions and what is your proposal?

John Lohrentz

Yeah, well, I suppose the first thing I just want to say is thank you for having me. It’s great to be here. The discussion on environmental taxation is obviously something that I’m quite passionate about.

So, to give you a sense of what my proposal covers, I started from this thinking around the centrality of agriculture to our economy and to our way of life in New Zealand. And I started to look at what was happening over the next 10, 20, 30, 40 years.

There were a couple of trends that start to really stand out to me. One was that as the impact of climate change grows, it’s going to change the conditions for farmers. And those changing conditions are going to have impacts on how we farm and how we need to adapt our farming practices for our new world.

I also was looking at the fact that our population is going to grow by about 2 billion people globally in the next 30 years. This is going to create challenges with food security and at the same time as consumers are also demanding really new and different things. We’re seeing the rise of alternative proteins, of different milks and also a desire for better types of meat and better dairy products at the same time.

Looking at all of that, I start to just look at the agricultural sector and dairy in particular and what the future transition needs to look like. And I became quite convinced that actually really pushing ourselves towards more innovation in the agricultural sector is going to be key for the transition as we go into a low emissions economy and thinking about that.

I thought actually one of the ways in which we could quite effectively finance that move towards a more innovative agricultural sector is through a progressive tax on biological methane emissions. And basically, what my proposal is, is to look at the way in which instead of us taxing, in essence, the gross emissions of farmers at the farm gate, what we could look at doing is actually setting a tax that is built around the target.

What we do is over time, we reduce that target towards our 2030 goal and the Zero Carbon Act and our 2050 goal further on. And then the challenge for farmers is to keep up with that rate of change. And for farmers that meet or exceed that rate of change, there should be a net benefit to them. They should actually be getting money back through this proposal. And for those that are behind, a tax is applied progressively to recognise they’re actually at the further ends of the spectrum, where you can pick out the easy early emissions reductions.

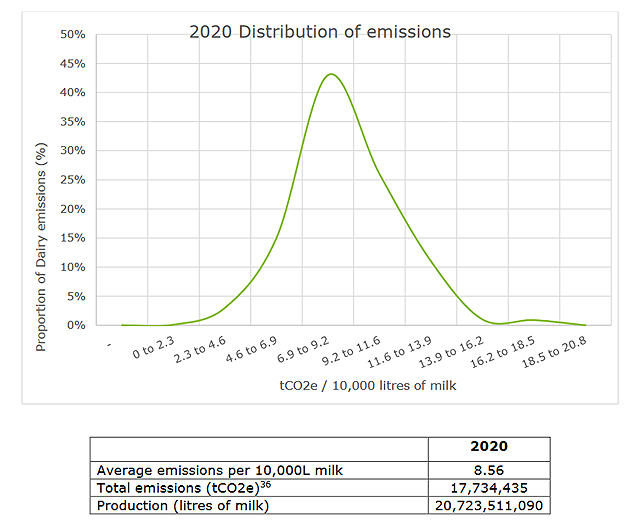

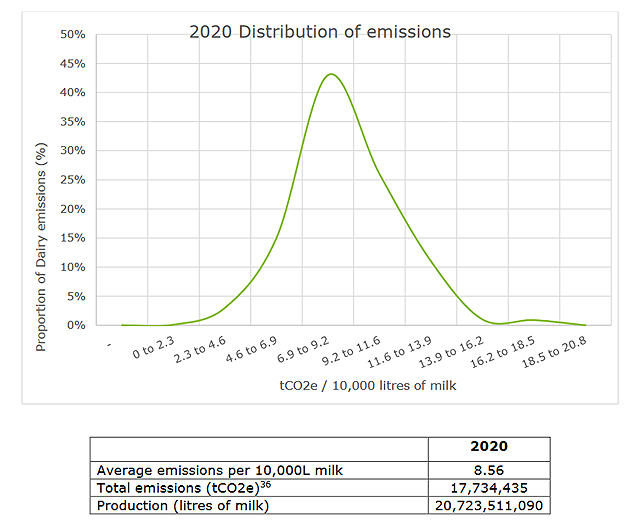

And I think one of the big benefits from taking this approach is that we actually take this idea of being penalised for your emissions out of the equation. And the question is actually per either acre of land or per 10,000 litres of milk, the produce or whatever measure we want to develop, what is the level of emissions for that production? And this gives us a way forward of talking about the idea of actually maintaining or increasing production while we look at ways to de-carbonise how we do that.

TB

I mean, that’s what I find really compelling about your proposal. In essence it’s a behavioural tax. But it’s not a sort of a sin tax, like tobacco duties, etc. where the idea is to eliminate behaviours. Your proposal is to use tax as a tool to encourage a change, because like it or not, agriculture is incredibly important to the New Zealand economy and will remain so.

John Lohrentz

Absolutely, yes.

TB

And tax is a dirty word in this. But the key thing you’re doing here is picking up a theme that Sir Michael Cullen raised, and I was very intrigued by as listeners to the podcast will know. He talked repeatedly about the opportunity of using environmental taxation to recycle in and help move towards the lower emissions economy. That’s a key part of your proposal.

John Lohrentz

Yeah. I’m actually really glad you mentioned the Tax Working Group because obviously they had some things to say about environmental taxation. And I think one of the things that stood out to me from their report is that they built this framework for environmental taxation. They said these are the kind of things that we think an environmental tax would need to do in order to be a good idea, essentially.

One of the key things that they looked at is there kind of an elastic relationship between introducing this that’s going to have some behavioural sort of impact. And their analysis of emissions-based taxes is actually yes, there is some responsiveness there. This is a good area when we talk about greenhouse gas emissions to introduce taxation and then recycle the revenue back into the place where that’s coming from. The classic example might be something like a fuel tax in Auckland. The idea is if we’re taking the fuel tax out of Auckland, you put that money back into transport at the same time.

The other thing that I was quite interested in was the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment’s Report on farms, forests and fossil fuels, which came out last year.

TB

You cite that report quite substantially in your proposal.

John Lohrentz

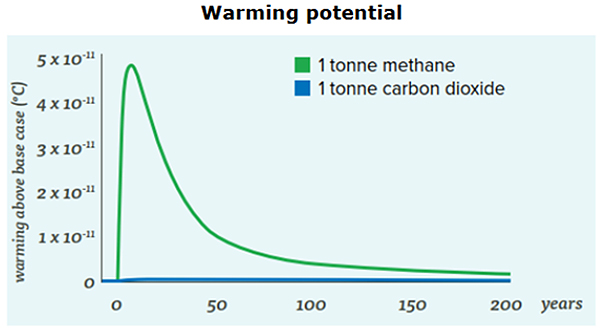

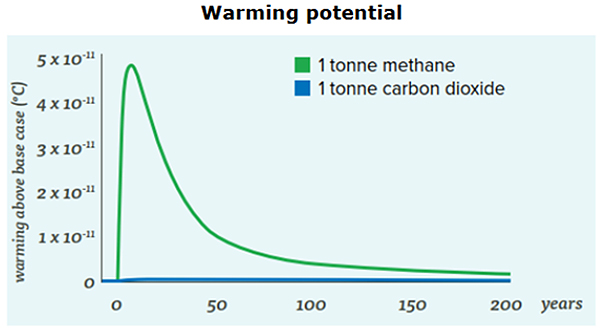

I really enjoyed it. And I think I think the reason it was quite gravitational for me is it was the first time I really clicked on the reality that we talk quite broadly about carbon or about greenhouse gases. But actually, there’s some real differences when we talk about methane as opposed to carbon dioxide as opposed to synthetic gases or nitrous oxide. And they all have different ways in which they impact on our climate.

Obviously, I’m not a climate scientist. I’m a tax interested person who is coming to an understanding of this. But in very general, in basic terms, a ton of methane that’s put into the atmosphere has a very, very strong impact initially. And then over time, that impact actually falls off as the gas is basically broken down in the atmosphere. Whereas if you emit carbon dioxide, the impact is lower initially, but it stays in the atmosphere for several hundred or even thousands of years.

When we start to think about how we design good policy, I actually think the beginning point for us is that we need to start with the science and have a really strong understanding of the different ways in which these gases are having an impact on our climate and then build back from that into actually thinking about the different ways in which we can approach these gases.

TB

And that’s actually one of the fundamental parts of your proposal, because what caught my eye when you’re looking at this, because people right away will say “Another tax! We’ve already got to deal with the emissions trading scheme!”

In your proposal, you’re saying take methane out of the emissions trading scheme and deal with it separately because of the science behind it. Do you want to talk a little bit more why you think that change in the ETS is important in this regard?

John Lohrentz

Yeah, I mean, first of all, I think it’s really important for me to say that I’m really happy to see the work being done on the emissions trading scheme. And also, I in no way consider myself an expert on it. But when we talk about interventions, when it comes to reducing emissions, the two broad ideas either are creating a price mechanism or this kind of cap and trade system, which is the emissions trading scheme.

And there are some real benefits from the emissions trading scheme if it’s done really, really well, which is if you include all the industries, all the types of gases, then you can kind of get to this point where you have a working market, to speak, for emissions. The problem is, is that if you have that one price, single price, there’s a risk that we actually distort the decisions we’re making about where we put the most of our energy in reducing emissions, recognizing that difference in the profile of different gases.

This idea that action in different ways is all substitutable so reducing a tonne of carbon is the same as reducing certain amount of methane I think is problematic. And Simon Upton the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment points that out.

Some of the proposals that have come out from the Interim Climate Change Committee,

Ministry for the Environment and also some of the work done by the Productivity Commission earlier last year has looked at this. They said, well, there are definitely some pros and cons to running with the emissions trading scheme and building on what we already have or looking at the opportunity to introduce a tax or levy. And the Interim Climate Change Committee actually recommended let’s go to Malta was a levy when it comes to methane emissions from agriculture, because the profile of it is really different. And it’s also really important for us to recognize the centrality and the primacy of agriculture in our economy.

TB

Just on that a levy would not gone down well with farmers straight away. And so what you’ve gone said, well, let’s go and look at methane. And there’s two parts to it as I mentioned earlier. There is a tax on emitters of methane above a certain threshold. But more importantly, you propose recycling the tax through Research and Development tax credits.

John Lohrentz

Absolutely. And if I if I was to try and articulate how I would actually talk about my policy to people, I think I would start by saying this is a focus on innovation. And I think the tax mechanism, as useful as a way of talking about how we raise revenue to support that in a potentially innovative and effective way. But really the central focus of what I’m proposing is a 40% targeted tax credit for R&D in the agricultural space.

I did some work with numbers from Treasury and other places to kind of get a sense of how we can make this work. And it looks like one way we could do this is we could use the tax revenues we collect and split them reasonably equally between this R&D tax credit, but also a refundable tax credit to farmers who are below that threshold I talked about earlier.

The idea would be for farmers who are really pushing to operate sustainably instead of having a tax payment because they still have some gross emissions, the fact that they’ve done work and really put some effort in is recognized and is actually a value that they receive back as a refundable tax credit. And then at the same time, we’re stimulating some of the technological advancements we need to really reduce emissions, which should accelerate the whole journey of the industry.

TB

And this is something that’s been talked about, the wider perspective by Fonterra and other is that if we can innovate in this space, the global potential is enormous, absolutely enormous, particularly because of the methane emissions. So, yes, that’s another reason I found it’s an extremely interesting proposal.

John Lohrentz

Can I talk to that a little bit more? One that one thing I’ve been reflecting on in preparing for our discussion today is the Tax Policy Charitable Trust scholarship competition.

Immediately following [the announcement of the finalists] the next day I was in Wellington and it was about a week after the Zero Carbon Act had been passed. I was just walking on the waterfront and quite a large group of people who were gathering ready to walk to Parliament for a protest. And it became quite evident quite quickly that this was a group of farmers that had come from all over the region and wanted to deliver their message to some of the some of the ministers. And I had the opportunity to walk and talk with some of them.

And one of the things that was just really impressed upon me through all of that discussion that I had is that this is an issue that is incredibly important to farmers. And I actually think our way forward when we start to talk about tax in this area is that we need to sit down at the table together and really have the opportunity to air the concerns of farmers because they’re working really hard and they’ve seen compliance go up and up over time. And actually, it’s been a very challenging industry in practice to be part of for the last couple of decades. You know, there’s been benefits, has been growth, but at the same time, farming is a challenging profession.

TB

Your report is full of little insights in there, which should encourage everyone to think about farming. For example, the current level of indebtedness in the farm sector. What is it? 35 per cent of farmers have a debt to income ratio per kilo of milk solids that’s more than five to one?

John Lohrentz

It’s about $35 of debt for every kilo of milk solids. And they may have changed since I wrote my proposal. But I think what it goes to illustrate the fact that over a third of farmers are living with that really high debt is a real strain. And that number specifically is with the dairy industry. I think what that indicates to us is that there are some people who are doing really hard work. And the problem with that debt is that at the end of the day, there’s a lot of other factors that can impact on the milk price. As it is you can do a huge amount of work and then barely breakeven even in a good year.

If we bring an integrated lens as to how we think about that journey towards sustainability, is we also have to be really thinking about the well-being of our farmers through this transition and all of the financial factors that actually go into making that sector successful. I think there’s a lot of really good stuff happening, and we just need to carry on and be really clear as to how we how we have this conversation together.

TB

Yes, I quite agree. We were talking off-air about this risk of the town versus country divide you hear about. And one of the things I think that makes what you’re proposing interesting and compelling is it addresses those issues because it encourages behaviour. It’s not ‘You’re naughty, you must reduce that’. You’re saying those who move along this path to lower emissions will get refundable tax credits and the innovators will get rewarded.

And that then points the whole industry away from this volume-based model. As I mentioned, with a debt of $35 per kilo of milk solids and the price at seven dollars, the ratio is five to one. But if the milk solids price goes down to six dollars, suddenly that ratio six or seven to one. It’s a hell of a risk to carry. And the banking sector, as farmers well know, is starting to draw back from lending to the dairy sector. Sale prices for dairy farms are flat as well. So, there’s a number of pressures coming on for the sector.

John Lohrentz

I think one of the pieces which is really point for me to acknowledge is I think our long-term future remains as an agricultural nation. I mean, especially when we think about the success of our regions, farmers are really integral to that. And I think that there’s this really incredible opportunity with how demand is shifting, especially overseas, to really champion the cause of highly sustainable agricultural products in all their forms.

TB

I couldn’t agree more. On transition you talked about 2030 as a target, but you are saying that about 30% of farmers are already meeting your proposal’s targets.

John Lohrentz

These are my estimates so they’re not perfect. I think there’s definitely some more work to be done to understand how this is looking. But just taking the dairy industry, for example, the kind of spread of emissions per 10,000 litres of milk produced at the farm gate basically follows a normal distribution, but with a little bit of a fat tail towards the heavier emitting side. I looked at this and the targets we’ve set ourselves as a nation now through the Zero Carbon Act.

And actually, as of when I wrote my proposal, about 14 per cent of farmers are already below the rate that we want to achieve by 2030. And so, it’s a move to try to move towards achieving our target, which is about 10 per cent reduction in methane emissions by 2030.

What it would look like is about half the farmers in the sector activating quite strongly so we move from about 14 per cent below that threshold to about a third of farmers, definitely below their threshold with a heavier tail kind of moving more into the mid-range. And I think that’s entirely achievable.

When the Biological Emissions Reference Group reported in 2018 they said that based on a lot of the technologies and practices we already have in terms of best practice for how to run a farm they believed it was possible to get that 10% reduction even if we don’t see some of the technological breakthroughs that we’re hoping to see in the next 10 to 20 years. So, even if a methane inhibitor or a vaccine is not developed, we can still definitely get to our 10% target reduction. But the reason I think we need to invest in innovation now is because that’s what’s going to give us the ability to unlock our success towards 2050 on a longer timeframe.

TB

And these are long run investment projects, to be quite frank. You mentioned the work the Tax Working Group did in outlining a framework we need to work on. What other environmental taxes do you think we could be seeing coming along following that framework?

John Lohrentz

That’s a great question. The Tax Working Group’s looked at obviously emissions as we’ve already talked about. And that was both from the perspective of a potential tax, but also the emissions trading scheme. They also looked at some of the existing environmental taxes we have, which are around solid waste such as the waste disposal levy. They looked at water abstraction and water pollution and then they also looked at congestion taxes. Then they started to foray a little bit into more novel taxes. There was some discussion around this idea of an environmental footprint tax or a natural capital enhancement tax. Leaving those last two aside, I do think that there is some potential work to be done in that space of taxes on water abstraction/pollution, solid waste and congestion as well.

These are all really interesting issues. But at the same time there is a confluence of potential environmental impacts, financial impacts and also social impacts from all of the decisions we make around that. And one of the things I appreciated about how the Tax Working Group approached this question of environmental taxes is that they were very clear that our goals in the short and medium term should be quite different from our goals in the long term.

Looking long term, what we need to be focussed on is actually how do we build up a new framework of environmental taxation that could be a stronger base for our economy and that could potentially take some of the pressure off other areas like, for example, income tax.

And that’s going to take some serious work because we don’t just need a framework. We need a whole new way of thinking of how we structure the design for how we do this well to ensure that it has equity both in the temporal sense and also a distributional sense. I think that’s the big work to be done. And we can definitely start that now. But it’s going to take time to build that framework out in the shorter term.

How the Tax Working Group thought about environmental taxation largely focussed on this idea of internalizing negative externalities. I think that there’s definitely some work to be done there to ensure that where potential environmental damage is occurring through pollution or water abstraction or other avenues, that there is more focus put on ensuring that people who are doing that are paying for that.

However, I think we need to move quite slowly and also recognize that our thinking on what natural capital is and how to best protect that is just evolving. There’s more work to be done to actually develop that theoretical base for how we approach this. We shouldn’t just kind of gung-ho go ahead into establishing all these new taxes. I mean, the reality is, is right now environmental taxation revenue is about 6.2% of the Government’s budget. And I definitely think that can go up. But the way in which we do that and think about the kind of counterbalancing that we do at the same time is very, very important.

TB

On environmental tax the OECD recently released a report on taxation of energy, which in fact was highly critical of just about every country for their approach to taxing energy and the inefficiencies from that. What’s your thoughts on the OECD approach?

John Lohrentz

Obviously energy is really central to our progression towards a low emissions economy. The idea of where do we actually get our energy from matters because everything we do uses energy in different forms. I think we’re doing quite well in New Zealand with at least 80% or 85% renewable for a lot of our sources, especially around Wellington where I think it’s close to 100% renewable now.

I think some of the challenges that are going to be really central for us over the coming couple of decades are going to be first of all focussed around different industries. I’ve chosen to focus on agriculture because I think it merits the time to spend a lot of our energy thinking about how the sector engages. I think also transport is going to be very interesting and I think forestry will be the element where there’s some real important conversations we need to have around what role forestry plays in our transition.

TB

Yeah, you mentioned forestry in your proposal, because just to pick up a point you mentioned earlier, one of risks about the ETS is we could be busily reforesting areas because that gives a good initial short term answer in terms of meeting emissions targets. But longer term that may not be the most efficient use of the land.

John Lohrentz

This is also coming from the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment’s report where there are some really interesting discussion going on about the expectations we have around the usefulness of tree planting. And the key thing that the Commissioner said essentially was we don’t want to get to a point in 2050 where essentially what we’ve done is scored a net accounting victory. We’ve got to near zero, but we actually haven’t done that really hard work to really decarbonise the emissions in our economy.

And just to be clear, I’m a gardener, I love gardening. I love things that grow. And from that, I have a very strong preference for this idea that we should be planting. We should be going for it. Native trees everywhere, just plant, plant, grow, let things reforest and go for it. I think the bigger challenge is looking at the whole picture and saying we can’t just pay for our sins and carry on committing them.

There’s this need for all of us to be responsible for playing our part, whether at the business level, economic level or personal level to reducing some of those emissions.

TB

I couldn’t agree more. And what I liked about your proposal is it encourages change, encourages focus on the issue. It encourages innovation, which for an agricultural economy like New Zealand represents a huge opportunity. This is a classic case of looking at an issue and turning the telescope around to say, “OK, there’s an opportunity here for us. How do we manage that transition?” I commend John’s paper to you all.

I think that’s a really good place to leave it there. John, thank you for joining us.

John Lohrentz

Fantastic, thanks for the opportunity to have a discussion. I’m looking forward to more in the future.

TB

Me, too. This will no doubt be the first of many environmental discussions that we’ll be having over the coming decade.

Well, that’s it for the week in tax. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time have a great week. Ka kite āno.

9 Dec, 2019 | The Week in Tax

Chris Cunniffe of Tax Management New Zealand talks about tax pooling and the latest TMNZ/CAANZ survey of tax agent satisfaction with Inland Revenue

Transcript

This week, I’m joined by Chris Cunniffe CEO of tax pooling company Tax Management New Zealand. Morena Chris, welcome to the podcast. Nice to have you here. Now tax pooling is something that’s been around now for what, 15 years? For me and many other accountants and tax agents, it’s a vital tool in helping manage clients’ tax payments. But how exactly does it operate?

Chris Cunniffe

It’s a good question, Terry. There’s a lot that happens behind the scenes that people aren’t aware of. So let me take a moment just to paint that picture. The tax pool is one really large account at Inland Revenue. It’s got multiple billions of dollars in it because we have clients ranging from New Zealand’s largest taxpayers right down to small businesses who pay their tax through the pool. When that happens, they deposit their tax in a bank account with our corporate trustee Guardian Trust, and Guardian Trust immediately passes that on to Inland Revenue. So the money is always sitting at Inland Revenue, but instead of being allocated at Inland Revenue against each taxpayer, it’s sitting in this large pool known as the TMNZ tax pool.

We have the ability to trade balances within that pool. So if somebody has paid too much tax, they can sell their excess. If somebody hasn’t paid enough tax, they can come to us and buy what they are short. At the end of the year, when people know their liability, we transfer to their account at Inland Revenue exactly the amount that they need. And their statement at Inland Revenue will show them to be completely compliant taxpayer with the right amount of tax paid on the right dates.

TB

Fantastic. It sounds a bit intricate. But what is the big advantage for clients of using a tax pooling method.

Chris Cunniffe

So the advantages differ I guess across the client base. Ultimately, tax pooling is about managing uncertainty around your tax payments. It’s around giving people an insurance policy that if they have underpaid, somebody is there to help them out. It’s particularly about managing exposure to Inland Revenue use of money interest. I’ll come back to that in a minute. And increasingly, for small and medium businesses, it’s about managing cash flow.

So let me just go back to the use of money interest. Inland Revenue charges taxpayers at the moment, 8.35% if they don’t pay their tax on time. Now, that rate is designed to hurt them. It certainly does. Inland Revenue does not want to be a an involuntary banker where people say, oh, look, there’s a fairly good interest rate there. I’ll just pay later. So they want to have a fairly sharp interest rate that focuses the mind and gets people paying their tax on time and use of money interest largely achieves that.

But there’s many reasons why people don’t pay their tax on time, and we’re not talking bad taxpayers. We’re talking people who have cash flow constraints, who have seasonal businesses, who have unexpected events that caused them to have taxable income that they hadn’t planned on. And for them to be hit with an 8% interest charge is kind of unfair.

So the genesis of tax pooling way back in the early 2000s was big business saying to Inland Revenue you’re charging us at that stage double digit interest when we don’t make our payment on time or we get our tax payments wrong. That’s usury. It’s unfair. So Inland Revenue came up with this idea that said, well what about allowing those who have paid too much to trade with those who have paid too little? And an intermediary can effect the payments.

So that’s what we do. So people will save probably 30% on the Inland Revenue interest. They’re going to charge them 8.35% We’ll be charging them a rate. And it varies depending upon the amount of tax you’re buying, the age of the tax but we’re charging around 5% to 6%, in some cases less.

TB

That’s a very significant advantage. It also means because the tax is deemed to be paid on its proper due date, you trade tax within the pool. And so not only have you reduce your use of money interest, you avoid the late payment penalties.

Chris Cunniffe

Absolutely. And there’s a 5% penalty if you’re a week late. So if you’ve missed a tax payment, tax pooling is an amazing solution. Just an example. Yesterday we had an inquiry, somebody at a largish company. Because it was it was over two million dollars was saying, can we buy a tax payment for 28 November? And right now they’re looking and down the barrel of a 5% penalty on that. They can come to us and buy that tax and we’ll just charge them an interest rate and they eliminate their late payment penalty.

TB

Seriously for those who have not used it before this is a real life saver at times. When’s the biggest demand for your services? Is there any particular time you’d see a lot of payments going through?

Chris Cunniffe

Oh, we run a regular cycle through the year. Most of New Zealand’s largest taxpayers deposit their tax through us and increasingly small and medium businesses are paying their tax. So as you go through the year. If you think about the cycle on P1, 28th August, a lot of money comes into the pool and then again for the P2 payment on 15th January and finally for P3 at the 7th of May after which it sits there until people file their tax return.

Now, like all good tax agents, I’m sure your filing percentages are right up to date, but there are some who seem to do all their tax returns of the last week of March. That is when we get frantic at that stage. Agents are coming to us and saying, here’s the tax liability for my client, please transfer. And that’s where agents are coming to us and saying, my client’s got a problem. They didn’t pay enough tax. Can I please buy tax? So we are frantic from March through till June. That’s our trading window.

The rest of the year it’s regular and routine transactions. Under the new provisional tax rules, interest now only applies from P3 on 7th May if people have used the standard uplift method. So most of the demand is for tax for P3 so seventh of May is the biggest date that we will sell tax for.

TB

So the changes to the provisional tax rules, they were designed to make life a lot easier for taxpayers. That probably made your life worse.

Chris Cunniffe

We were disrupted without doubt, but I don’t think there’s a business in New Zealand that doesn’t get disrupted by competition or by technology or in our case, by regulation. Yes. And what it’s forced us to do is look at “What are the services we provide? What are we good at doing?” And looking at our client base and so. Whereas we originally existed, I guess, as an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, “my client is short paid can I buy tax?” We have now morphed into being a cash flow and a working capital solution, particularly for small business.

So it will be no news to you – what’s the biggest issue for your clients? Cash flow. Inland Revenue is quite prescriptive. You shall pay tax on these dates depending on your balance date with no care about whether you’re a seasonal taxpayer, whether your business is growing, whether there’s any other things going on. Too often those dates don’t fit with your business needs.

So paying tax on the 15th of January, straight after Christmas and when everyone’s in shutdown mode, how dumb is that?

TB

Indeed, there’s a story behind that which can wait for another day.

Chris Cunniffe

Anyway, we increasingly have people saying, look, will you pay tax on our behalf? We could give you an example of some people who use us for cash flow. Trucking company wins a major contract. Great news. The business is going to grow. What we need is to buy three more trucks. I need to pay my property tax. Now, where’s the best use of their cash right now? It’s obviously putting down deposits and getting new trucks into the fleet. So they came to us and said, can we defer the payment of our provisional tax for six to nine months? And we said, of course you can. So, we have this product we call it tax finance and you essentially tell us I’m due to pay tax on a particular date, let’s say the 15th of January coming up. It would suit me better if I could pay that in six months time. So we will get a funded pay tax on your behalf and you pay us a fee upfront and in six months time when cash flow is strong you come back and you essentially buy that deposit out of the pool. We transfer it to Inland Revenue you’re a compliant taxpayer. You’ve paid your tax on time. So that’s one way to do that. Kind of “I know exactly what I need to pay and I want to defer it in a structured way”.

The other way is just to do it like having a revolving credit or a flexible mortgage. You say, “I know what my liability for this year is and I want to pay it through TMNZ and I’ll pay 200 dollars a week.” We had a lot of clients who do that and they just set up that automatic payment to pay it through us and we transfer it across and we work with the tax agents to make sure the tax is on the right date at the right time. But for that taxpayer and sometimes even for the agent, all that stress about whether the money will be still in the bank account when it’s time to pay the provisional tax will is gone. We often hear agents that tell us about clients who when they get the provisional tax reminder they go “Whoops, I’ve just spent that.”

TB

Yeah, that’s fairly common. There wouldn’t be a tax agent in New Zealand who hasn’t experienced the call on the morning of the 28th August, for example. “So what’s this about paying ten thousand dollars? I haven’t got it”. I mean what are you describing here is something that anyone who works in the SME sector knows, that a lot of the legislation and processes are designed for big companies and assume a level of cash flow and capital and basic skill that just simply doesn’t exist or is not commonplace in this sector.

I mean, we’ve talked about provisional tax, but actually you can also cover GST and other taxes. How does that work?

Chris Cunniffe

We can cover other taxes where there’s been a reassessment. Where you’ve got an uncertain position, and this could either be that Inland Revenue has approached you and questioned a tax position you’ve taken or increasingly it is where the tax agent has done a review and says “I don’t know that we got this quite right” and a voluntary disclosure is going to be made. You can come to us and buy tax at those historic dates. This is incredibly valuable. If you if you think that interest rates over the last four years have fluctuated between 8% and 9%. So take a client who has been getting a position wrong for the last four years. The interest that has built up on that underpaid tax there could be north of 30% of the core tax, so that’s quite an uncomfortable conversation to be having with your clients as you talk them into a voluntary disclosure or when Inland Revenue is putting a proposal for a reassessment on the table and then they went 30% extra with interest. This is before we even get to penalties.

We’ve got tax in the pool going all the way back to 2008. It does not matter what date your client is being reassessed for. We’ve got tax available. Anybody who is being reassessed for any income tax or any other tax type, you should contact the pool and we’ll be able to reduce their interest costs in the region of 30% to 40%.

TB

That’s a significant help. This is a scenario we see quite a bit often around overseas income because the rules are so complex and people assume that it’s just like to be taxed at source. So, yeah, the ability to make a voluntary disclosure and get a reassessment and then use TMNZ to reduce the interest bill is very significant. In one example I can think of we saved a client $10,000 in interest by using tax pooling.

Chris Cunniffe

Yeah. And this is real money for people who in most cases were unaware that they had a problem.

TB

It’s the old saying you don’t know what you don’t know until you find out. And then it gets very expensive. So obviously, a key part of your business would be regular interactions with Inland Revenue. And at several different levels. So how does that work? There is a special unit within Inland Revenue that deals specifically with tax pooling.

Chris Cunniffe

Well, let’s take a step back. Inland Revenue created tax pooling, it was the solution to a problem that arose in the early 2000s. So we exist at the behest of Inland Revenue. So at a policy level, we have engagement with them, which is around what should tax pooling be able to be used for and how has the industry evolved? I talked about how we changed over the years. We have regular discussions with tax policy officials. Just to let them know what’s happening and make sure that, you know, they are comfortable with the settings. So that gets a gets a big tick.

And about four years ago, Inland Revenue did a review of the industry just to check that there was no risk to the system by having this industry called tax pooling.

And it came back with a very solid report, in fact one of the recommendations was this is now relied upon by so many taxpayers, you would not want to take it away.

Operationally, there’s a unit at the processing centre and on a daily basis we’re interacting with them. We’re uploading schedules, we’re saying this is who’s put money into the pool, this is people who are buying tax. Please transfer from the pool to these taxpayers X amount of tax. We do tens of thousands of transactions a year with that unit. So we work very, very closely with them.

And as you can imagine, with all interactions with Inland Revenue just around the fringe, there can be systems, issues or uncertainty about legislation. And we work through that. And that final piece of uncertainty with legislation is in a technical area at Inland Revenue that we liaise with and there’s a regular liaison between Inland Revenue and the industry to ensure that issues are running smoothly. We pay a massive amount of New Zealand’s provisional tax. TMNZ would be the largest taxpayer in New Zealand. If you think about our account at Inland Revenue with multiple billions of dollars in it. So there’s a an investment on both sides to make sure that this runs efficiently.

TB

Yes, the tax pool has at any one time six or seven billion dollars?

Chris Cunniffe

It can get well north of that when is all the money comes in. And then as it gets transferred out, the pool drains again and then we fill it up for the for the next year. But it’s in the multiple billions of dollars.

TB

I understand included amongst your clients is the New Zealand Super Fund, the country’s single largest provisional taxpayer, with a billion dollars plus regularly. So it’s dropping 300 million at a time every provisional tax payment.

Now we’ve got a provisional tax payment coming up on the 15th of January. So now tax agents like you will be looking out to our clients and telling them what’s going on. But as you know the rules, 105% or 110% of RIT [residual income tax] are confusing. I think you’ve got a specific tool to help tax agents like myself and clients calculate your RIT and your payment.

Yeah. A couple of years ago, Inland Revenue looked to simplify the provisional tax rules to take the heat out of the use of money interest by saying if you pay your first and second installments based on an uplift to prior year returns, then there’s no interest. That’s good for business, but they’ve created a level of flexibility and an optionality in the system that has actually now started to confuse people. As you say, should it be 110% of two years ago or 105% of last year? Have I filed my last year’s return or not? It starts becoming quite a complex calculation. So we’ve created a calculator on our website which allows agents to enter the details of their client’s prior tax positions. And it will come up and say this is how much tax should be paid on on each installment date. And so that’s become very popular with agents. And they tell us it is now a core part of their provisional tax process in terms of advising clients.

TB

Excellent. Yes, even for someone who’s been like myself working for 25 years or more, provisional tax every now and again, I just go back and say “Wait a minute. What applies here? Do we file a return or not file a return?” It’s all sort of needless complexities and confusion. So it’s always invaluable the assistance we get from yourself.

Chris Cunniffe

And again, that’s the advantage of the pool is that you can kind of pay what you think you owe. But if there’s overs or unders at the end of the year, you can work with us to smooth that out. We shouldn’t be stressing before Christmas about provisional tax.

General satisfaction with Inland Revenue engagements well down

TB

Yes, but we have to. Now a big part of your daily routine is interaction with Inland Revenue. And in recent years, you actually started conducting an annual survey of tax agents views about satisfaction with Inland Revenue. And the latest iteration was released at the Chartered Accountants Australia New Zealand tax conference that I was at two weeks ago. Now, this is a fully professional poll carried out by Colmar Brunton. And how did, what was the survey’s results?

Chris Cunniffe

That’s right Terry. We have run the survey for the last nine years in conjunction with Chartered Accountants Australia New Zealand. It’s designed to elicit feedback from agents or tax professionals generally about how their engagements with Inland Revenue have gone. I guess the key out-takes from this year [is] it has been a tough year and the general satisfaction on Inland Revenue engagements is well down.

Let’s take a step back and think why that is though, and acknowledge that Inland Revenue have just implemented probably the single biggest technical or system transformation in New Zealand history with millions and millions of accounts for taxpayers being moved from the old FIRST system to the new START system and the movement of that data went without a hitch. Unfortunately, as happens with all major transformations around the edges, there’s a few challenges and these played out and all agents will be aware of these if they think back to what life was like between April and July this year.

TB

We’d rather not.

Chris Cunniffe

Yes, the auto refund, they thought this was a good idea, but in many cases the money was sitting with Inland Revenue for a damn good reason and the agents knew why it was there. And if you take it back to first principles, agents know their clients’ tax affairs and should be trusted to manage them. The getting hold of Inland Revenue on the phone became a nightmare. Correspondence slowed down – mixed views on this – but they stopped doing audits. So if your business consisted of advising taxpayers through audits, that was a bad thing as all the auditors were pulled in to answer correspondence.

The survey showed that the overall satisfaction with Inland Revenue has been declining since 2015, which corresponds with this massive transformation change they’ve been going through. It’s now at 66%. It had been right up into the into the 80s.

People in public practice are the ones who are expressing the greatest dissatisfaction with the engagement. That probably makes sense because they deal with Inland Revenue on a much more regular basis than those in business. And to be fair, I think if you are in business, the new system is much more intuitive and much more immediate. And so, yeah, there’s a winner in that area. If you’re in practice, the frustrations we’ve talked about have come to the fore.

The dissatisfaction with phones is very, very strong. This is nothing Inland Revenue doesn’t know. They get feedback all the time. The advantage of the survey is it’s kind of like a mark in the sand and we’ll be able to track over time how they perform. We would expect that next year we should see an upturn in satisfaction with contacting Inland Revenue by phone or by for processing purposes.

TB

Inland Revenue seems, however, to be very much driving its business model to take everyone going online. And from their business perspective, that makes sense. It reduces maintaining a large call centre staff. It probably would be comfortably the largest in the country by a long way. I remember one time hearing from a person at Inland Revenue who had handled a call centre for a bank. And the one thing he hadn’t realised just was what was involved – whereas for a bank call centre, the interaction was designed to be kept to two minutes or so. But for Inland Revenue, basically anything goes, and that’s something that he hadn’t realised the issues around that. So the call centre issue is one I think we will want to watch very carefully how that proceeds, because the nature of tax being what it is.

And this is also a reflection of the fact that Inland Revenue is a largely trusted organisation. Understandably, people will want to talk to Inland Revenue and say “Have I got this right?” So it’s a double edged sword for Inland Revenue. It might want to move people online, but its stature and trust within the community means it’s going to get a lot of calls. Tax agents as well want a bit of reassurance because here’s the thing. There are about 5200 tax agents registered and that would include organisations as big as PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst and Young, Deloitte, – the huge mega firms who have hundreds of accountants down to your sole practitioners. But the majority are sole practitioners. And it’s lonely out there. And we carry the can if we get it wrong. So every now and again, it’s nice to have a voice at the other end who said, yep, that’s right or no, you need to do it differently.

Chris Cunniffe

It’s a very good point. And there’s a real point about what is the psychology of engaging with your regulator. Clients in particular are worried when Inland Revenue contacts them. They think, have I done something wrong? So there’s a there’s a real fear. And Inland Revenue has invested a lot in trying to show off a friendly face. But they still are a regulator. Tax is a really big issue for people. It’s not something that they feel qualified to do. And the stigma and the consequence of getting it wrong is significant penalties and interest. For an agent you wear that because if you have advised your client and got it wrong, the client is pretty grumpy and would expect you to be responsible for the consequences.

So I agree there is a need to be able to get the right assurance and the right level of engagement where appropriate. On the other hand, a really good system design would say we make it really hard for you to get it wrong. We give you all the easy and all the basic information you need. The most popular question asked of Inland Revenue call centre staff is “What is my IRD number?” There’s an engagement if they can get rid of that, you would free the staff up to answer the high quality calls where there is genuine uncertainty and people do need to be guided. So Inland Revenue has got that challenge. But I think it’s essential for agents in particular that when there is uncertainty, they can talk to somebody and figure out what’s going on. So getting that service available and an effective fit for agents, I think is a top priority for Inland Revenue.

TB

Yes. That’s an amazing thing. And people ring up asking “What’s my IRD number?” That’s going to be a very circular conversation. I think education is going to be very important about people understanding the system, and that’s everybody. I think the classic example this year, it’s emerged, is a one and a half million people got their prescribed investor rate wrong either under or over. So there is something where everyone needs to work out. There was an assumption that people knew more about this, were watching it regularly, and there was an assumption that because of the auto default rate, Inland Revenue and the KiwiSaver funds were all getting it right. So everyone was sort of assuming everyone else was looking after what they should have been looking after and of course, it landed up in a big mess in the middle.

So, yes, Inland Revenue is still going to have an educator role. I think in many ways it probably needs to be putting more resources into that. We run a self-assessment system, which means we’re supposed to know and assess our own position. But even though our tax system is widely regarded as one of the more conceptually straightforward in the world, you get around the fringes of GST or the financial arrangements regime, or even the Brightline test all those little quirks in them, which keeps people like myself in business, but means that you can’t really work on a true yes, you can work out this tax for yourself.

Chris Cunniffe

It’s interesting, over the years Inland Revenue had pushed away the salary wage earner, the man or woman in the street. “You didn’t need to file tax returns”. So a lot of people were totally unaware of how Inland Revenue works, how your tax system works. And that leads to things like when you are asked by your bank or by your fund manager, what is your tax rate? People are kind of oblivious to this. It led to the expansion of the tax refund companies charging for a service that anybody themselves could have done online, but people just weren’t used to being in the tax system that the new platform now brings people in a lot more.

And the interaction with investment income and with PR, they have lifted a rock and found out there’s actually quite a lot under there. That was everyone was oblivious to it – be it by design or by accident. People were on the wrong rates. I suspect that’s an example of something that wasn’t really thought through particularly well. It should take us a period of time to get it right before going forward it will be set and forget. But you’re right, there’s a number of other places where people get drawn into the system. So the bright line test, the other person who has one property, one investment property, you’re now in the system. The increased amount of information that Inland Revenue will be getting from foreign tax authorities, from the banks and from the investment funds means that they will be asking questions if all your settings are not right. So I think there’s a lot more engagement or interaction going to happen between individuals and the department.

TB

Yeah, that’s definitely coming. Definitely. And the survey was fascinating to be part of it because the Commissioner then spoke immediately afterwards, talk about the wrong warm up act. How did you think she responded? She responded to the criticism that clearly could not be ignored, but also was also looking forward. How much confidence you draw from what her summary of where things were at?

Chris Cunniffe

It worked very well that I was able to report the survey. And one of the main issues out of the survey – if we take away the what’s general satisfaction like in a year where there’s a massive transformation – the biggest gripe that’s been coming through had come from tax agents around Inland Revenue approaching their clients directly. And I think this was a philosophical thing in some ways from Inland Revenue, “we want to talk to people that ultimately, they’re the customer. We can get there and share information with them”.

But what that was doing was frustrating agents immensely. And we got really, really strong feedback from agents, around 72% of them said Inland Revenue had gone to their clients directly and we don’t like that.

TB

Can you imagine if you’re in business – any businessman – and one of your rivals approach 72% of your clients? You could see why the tax agent community was seething.

Chris Cunniffe

Indeed, because in the feedback we got was things like ” this worries my clients needlessly” because the agent often would have it all under control – as a GST refund about to be released. It’ll cover that liability, it’ll all be squared out and the client’s got this phone call “you haven’t paid your tax. What’s going on.” That undermines the agent in the eyes of the client. “I thought, Terry, I paid you to look after my affairs. I’ve got Inland Revenue in my ear saying I’m in arrears. What’s going on?” It means that you as an agent have to then spend time talking to the client, calming them down. You probably can’t charge for that.

So there was a lot of needless angst. Inland Revenue has found that there were 72 letters or interaction, real written interactions going out to clients that probably should have gone to tax agents. They have worked through the system and have now re-pointed those so that they will go to the agents in the first place and they will only go to the client where the agent becomes non-compliant. Or they will go to the client directly if there’s thing’s like a change in bank account number. That’s proper, that’s an updated security check.

TB

I hate to say this, but it’s one of the more common frauds I’ve encountered where the tax agent alters a client’s bank account details that refunds go into the agent’s bank account. I encountered that a number of times. So Inland Revenue is absolutely proper to be sending authorities like that to clients as well as tax agents.

Chris Cunniffe

But what they have acknowledged now is their settings were wrong. I think it was a deficiency in the new system that they’ve got that it’s not particularly geared around the New Zealand system and the way that we use agents. It is an off the shelf system. So it has needed some adoption.

But it was getting to the stage, and Terry I know you’ve been vocal on this yourself, about Inland Revenue’s engagement with clients. You and a number of others have been very vocal about this saying “This is wrong”. And I’ve I talked to an awful lot of agents and they’ve been saying to me, is there a strategy at Inland Revenue to displace the agent, to essentially disintermediate, get them out of the system?

So I put that question at the conference and the Commissioner basically got up and her opening comment was, “Let me affirm the place of tax agents in the New Zealand tax system”, which I think was music to the ears of tax agents. She then talked through the changes that have been made and the fact that they’re kind of inverting the pyramid to say our default position is we’ll engage with the agent. As an agent you can control this if you’d rather the client dealt with maybe the payroll or maybe that the GST, you can you can adapt adjust the settings to do that.

So look, that was a major success because the agent community felt like they were banging on the door and not being heard. And I think we finally had pulled all the strings together and I was very grateful to the Commissioner for her immediate response and the fact she stood there and said, “look, this is where we see agents. This is what we’re doing. We’ve got a strategy around it”. I’m hopeful that in a year’s time we’re not talking about this.

TB

So am I. And I think also the other thing was interesting about your survey, and this is something we’ve seen when business transformation first came along. A lot of agents I was speaking to were nervous about it “have we got a role in the future?” But the survey shows very much the feeling is, “yes, we definitely have a role in the future” and they are adjusting their business model to something which is more appropriate to an advisory client, helping clients with cash flow issues and using tools like TMNZ and getting ahead of the tax issue so being proactive rather than reactive. And the survey showed those results, didn’t it?

Chris Cunniffe

It did. And it’s been a theme that we’ve asked for the last couple of years, essentially for the reasons that you ask. I talked about disruption so that the model of doing a basic tax compliance programme where you do everything for your client is largely dead because the software companies have got to the stage where clients can do a certain amount of it themselves. How far the client goes along that that process is a discussion between the agent and the client. But you’re right, agents are looking to move up the value curve and be less about someone who will process a set of accounts and tell you six months or nine months after year end whether you made a profit or not, to somebody who engages with you in real time around how your business is doing.

TB

Well, I look forward to seeing the survey next year. And I think that we’ll leave it there. Going to be an exciting twelve months ahead, another release coming forward. And so the commissioner reassured us about how they were managing. So it’s a wait and see. But thank you very much, Chris, for joining us on the podcast. It’s been absolutely insightful and fascinating. I really appreciate you coming over.

That’s it for The Week In Tax. Next week will be the final podcast of the year and we’ll have a retrospective on the big events of the year. In the meantime, I’m Terry Baucher, and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients, until next week. Have a great week. Ka kite āno.

26 Nov, 2019 | Tax News

1966 and all that: The chequered history of entertainers, sports stars and tax

What have William Shakespeare, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, U2, Norman Wisdom, Richard Burton, Boris Becker, Lionel Messi, Christian Ronaldo and Bobby Moore all got in common? They are but a few of the many, very many, actors, entertainers and sports stars who have found themselves in trouble (sometimes bigly) with the taxman.

One reason entertainers and sports stars run into money and tax problems so frequently is that they work in an industry where vast sums of money can be generated practically overnight from all around the world. Consequently, musicians and bands probably have some of the most complex tax affairs outside of multinationals. It’s therefore unsurprising many engage in elaborate tax planning and it’s equally unsurprising this sometimes comes unstuck with expensive consequences.

This Top Five looks at actors, musicians and footballers who left a tax legacy as well as an artistic one. Moreover, these tax legacies remain highly relevant today.

1. “Know you of this taxation?” (Henry VIII).

Despite his colossal cultural legacy, we know very little about the real Shakespeare. We do know that between 1597 and 1600 he appears in several rolls for the “lay subsidies” for the St Helen’s Bishopgate parish in London. Lay subsidies were a form of local wealth tax on local householders. The lay subsidy roll contained an estimate of a person’s wealth and the amount assessed.

It appears that in 1598 Shakespeare defaulted on his lay subsidy for the year of 13 shillings and four pence. It’s not known whether this debt was ever paid but since about this time he bought into the Globe Playhouse for £70, he was surely not short of money. This has led to much conjecture about whether Shakespeare was one of the first known tax avoiders of the entertainment industry.

Like so much else about the man, we’ll never know the truth about Shakespeare’s finances. I can’t help but wonder if the quip in Henry VI“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers” might reference some dud tax advice he received.

2. From Abbey Road to Exile on Main Street.

It appears The Beatles were pioneers in tax planning for musicians. Very early on in their career they were introduced to accountant Harry Pinsker who specialised in the entertainment area. (Pinsker’s first reaction was that “they were just four scruffy boys”).

One of Pinsker’s recommendations was a songwriting company Lenmac through which their earnings would be channelled. He successfully argued the company’s income should be taxed as trading income rather than investment income which would have incurred higher taxes.

Even so, the very high tax rates of the mid-60s (more than 90%) prompted George Harrison to write Taxman.

“One, two, three, four, one, two

Let me tell you how it will be

There’s one for you, nineteen for me

‘Cause I’m the taxman, yeah, I’m the taxman”

Pinsker ultimately suggested the formation of Apple Records as a tax effective means of managing the band’s revenue. His efforts did not go unnoticed by the Beatles. During rehearsals of their final album Let it Be, the band started singing Harry Pinsker instead of Hare Krishna.

The Rolling Stones weren’t as well managed as The Beatles and in 1971, facing huge tax bills, they moved to the south of France where they recorded one of their greatest albums: Exile on Main Street. The title was a deliberate reference to their tax exile.

Having also fallen out with Decca Records and their manager Allen Klein, the band took control of their affairs at this time by forming their own record company. They also established a Netherlands company to shelter their income. This started a trend which other bands including U2 would follow.

The Rolling Stones move into tax exile didn’t attract much criticism at the time, perhaps because the rates of tax they then faced were so high. Forty years on attitudes have changed.

U2 were in town recently and their tax practices have drawn increasing criticism. Lead singer Bono has been accused of hypocrisy after he was linked to the Panama Papers.

In 2015 Bono and U2 were criticised for making changes to shift royalties through the Netherlands to take advantage of a special concession. Now it appears this concession is ending.

If U2 still haven’t found the perfect tax structure they were looking for, The Rolling Stones should remind them “You can’t always get what you want.”

3. The slapstick clown with a tax lesson for crypto-asset investors.

The British comic

Sir Norman Wisdom rose to fame in the 1950s playing a hapless but good-natured incompetent who somehow through a combination of slapstick humour and good fortune saves the day.

Contrary to his clownish on-screen character, Wisdom was a very shrewd investor, and this ultimately resulted in one of the more notable and still influential tax cases of the 1960s.

In 1961 Wisdom invested in silver ingots as a hedge against a possible devaluation of the British Pound, eventually realising a profit of £48,000 (about £800,000 today). At a time of very high personal tax rates Wisdom claimed the profit was a tax free capital gain (the transaction occurred prior to the introduction of capital gains tax in Britain).

Wisdom won in the High Court but in 1968 the Court of Appeal in Wisdom v Chamberlain (Inspector of Taxes) determined that the transaction was in the nature of trade and therefore taxable. Wisdom paid the tax due and outraged by the high taxes then went into tax exile in the Isle of Man where he lived until his death in 2010.

His case is often cited when considering whether a transaction is of a revenue or capital nature. In 2017 Inland Revenue cited it in a “Question We’ve Been Asked” on whether the proceeds of the sale of gold bullion would be income. (The short answer is almost certainly).

Inland Revenue also consider some crypto-assets to have similar characteristics to bullion. It is therefore probably only a matter of time before some crypto-asset investors will need to acquaint themselves with Wisdom v Chamberlain and Norman Wisdom’s unwilling tax legacy.

4. Gone for a Burton.

Richard Burton was probably too busy being one of the great actor hell-raisers of the 1960s to be paying attention to the price of silver bullion. Yet, he too has left a tax legacy, one of particular relevance to many of the thousands of Britons currently living in New Zealand.

Burton became a tax exile in the late 1950s after taxes had reduced his earnings of £82,000 for 1957 to £6,000. (Allegedly he subsequently remarked “I believe that everyone should pay them [taxes] — except actors.”) Burton moved to Switzerland where he lived until his death in 1984.

Burton was buried in Switzerland, apparently in a red suit together with a copy of Dylan Thomas’ poems. However, many years earlier when he was married to Elizabeth Taylor, Burton had acquired two burial plots for himself and Taylor in the Welsh village where he had been born. And this proved extremely costly for Burton’s estate.

Inland Revenue argued successfully that the presence of the burial plots together with his Welsh themed funeral meant that Burton had never lost his UK tax domicile. Accordingly, his estate worth just over £4 million had to pay a total of £2.4 million in Inheritance Tax.

In my view Inheritance Tax represents the greatest tax risk to anyone either born in the UK or who owns assets situated there. The lesson from Richard Burton’s death is that Inheritance Tax could still apply many years after a person has left the UK.

5. England, One; HM Inspector of Taxes, Nil.

November 22 was the anniversary of when England won the Rugby World Cup in 2003. In the wake of England’s unexpected defeat by South Africa I saw a perhaps rather too gleeful tweet asking if 2003 was destined to become English rugby’s equivalent of England’s sole football World Cup win in 1966.

On the other hand, the RFU’s Treasurer possibly breathed a sigh of relief after the final as apparently the squad stood to win bonuses totalling over £6 million.

Anyway, back in 1966 the English Football Association rewarded its world cup winning squad with £1,000 each. (About £15,000 in current terms or only 30% of the English Premier League’s current AVERAGE weekly wage of £50,000). Enter the Inland Revenue stage right in the form of HM Inspector of Taxes Mr Griffiths. He considered the amounts paid to England’s captain Bobby Moore and cup-final hat-trick hero Geoff Hurst were taxable as they formed part of their remuneration.

The case finally reached the High Court in 1972 where Mr Justice Brightman ruled the £1,000 payments were non-taxable as they had the “quality of a testimonial or accolade rather than the quality of remuneration for services rendered”. A convincing one-nil win then.

Other footballers haven’t fared so well against the taxman: Lionel Messi and Christian Ronaldo are unquestionably two of the greatest players of this generation, but their tax planning has not matched their sublime footballing skills. In 2017 Messi had a 21-month jail sentence for tax fraud commuted to a fine. This was in addition to a voluntary €5m “corrective payment” he and his father had made in August 2013. Earlier this year Ronaldo was fined €18.8 million for tax evasion and given a suspended 23-month jail sentence.

5B. Beware the Ides of…November?

Finally, 22nd November, was also my father’s birthday. It’s actually a pretty momentous, if not infamous, day in history. Most notably in 1963 when President John F Kennedy was assassinated (with both Aldous Huxley and C.S. Lewis also dying on the same day the obituary writers had a very busy day). Charles de Gaulle was born on this day in 1890 and Angela Merkel became German Chancellor in 2005.

There’s a tax connection in convicted tax evader and serial tax exile Boris Becker who was born on this day in 1967 and the obligatory Kiwi connection is the death in 1982 of the pioneering aviator Jean Batten.

Lastly, Margaret Thatcher resigned on this day in 1990 (as a result of, you shouldn’t be surprised to hear, a Conservative Party split over Europe). This was not only a pretty funny 60th birthday present for Dad but also something of a rich irony as he was a staunch Thatcher supporter. Miss you Dad.

25 Nov, 2019 | The Week in Tax

- More on Inland Revenue CRS initiative

- The future of tax

- Why did the Tax Working Group’s CGT proposal fail?

Transcript

This week, an update on Inland Revenue’s Common Reporting Standard initiative, the Future of Tax and what went wrong with introducing a capital gains tax.

I spoke recently of Inland Revenue’s new initiative on the Common Reporting Standard on Automatic Exchange of Information or CRS as it’s commonly referred to. This is where Inland Revenue has received details of upwards of 700,000 accounts from overseas tax authorities. It is now working its way through that list of information it’s received and has started to send out some letters to people where it considers there has been either under declaration or non-declaration of income.

I’ve found out a bit more about what’s going on with this initiative, and it’s a little bit concerning how it’s being approached. So far Inland Revenue has sent out approximately 4,000 letters to various individuals with the latest batch of letters going out in the last couple of weeks, in fact.

But it seems to be slightly indiscriminate in its approach, I’m hearing reports of transitional residents who don’t have to report overseas income, receiving such letters and then having to spend time on it.

The information that’s been sent is for the period to 30th June 2018, and there’s another set of information coming for the period to 30th June 2019 very shortly. And apparently Inland Revenue is asking people to reconcile the numbers it’s received with what’s in their tax returns, because there are sometimes big discrepancies.

[Sometimes] the reasons for those discrepancies are because the taxpayer has returned income under a special regime, such as the foreign investment fund regime or the financial arrangements regimes. The financial arrangements regime, as you may recall, deals with income on an accrual basis and brings into account unrealised foreign exchange gains.