When hearing the lamentations about the purported cost and harshness a capital gains tax (“CGT”) will bring, I think of Paul1. Dying of cancer he applied to his UK pension scheme for an early payment. Paul died before it arrived, but his widow still got to pay the tax on the transfer.

I am reminded of Judy and Wayne, hard-working specialist nurses living in Auckland, who also transferred their UK National Health Service pensions to New Zealand. They too got a tax bill for their troubles even though it would be five years at the earliest before they could withdraw any cash. Judy and Wayne could not even withdraw funds to pay the $50,000 tax bill. So, in order to meet the bill, a pair of highly skilled nurses in a sector and city with chronic shortages, sold up and moved to the South Island. A real triumph of tax policy.

Nothing the TWG proposes in its final report will be anywhere near as penal as the present rules for taxing foreign superannuation schemes. Or, for that matter, the financial arrangements and foreign investment fund (“FIF”) regimes that will also remain in place. Amidst some of the frankly hysterical reaction these important details have been overlooked.

Listen to Terry discussing the TWG report with Jenée Tibshraeny journalist at Interest.co.nz

The TWG proposes extending the range of assets that will be specifically taxable on disposal. It’s therefore not a CGT in the sense of a specific part of the Income Tax Act covering all capital transactions. Rather it is, to borrow a phrase, a backstop, applicable if the transaction isn’t taxed elsewhere.

I do not read too much into the minority report by three of the TWG members. It is unusual but should not be a surprise: tax experts by their very nature are an argumentative bunch at the best of times and are as divided over the issue as the general public. What is interesting about the minority view is that all three, including long-time CGT sceptic Robin Oliver, support taxing disposals of residential property.

That, together with comments in the report that the Government doesn’t have to accept all the TWG’s proposals about extending the taxation of capital, opens the door for a partial extension only on residential property investment.

The issue will dominate politics between now and next year’s election and the Government will need to decide quickly if the relevant legislation is to be in place before the proposed start date of 1 April 2021. In this context, Inland Revenue’s capability to deliver will be tested, which prompted Michael Cullen to remark that it might need support from countries that have CGT regimes to help get the legislation ready. He and the report also stressed the need of ensuring Inland Revenue is properly resourced and keeps its most skilled staff, which according to Cullen isn’t happening at the moment.

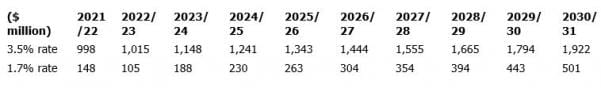

Although a CGT is the preferred option, the TWG report does consider the use of a deemed return method similar to the fair dividend rate applicable under the FIF regime. Table 5.1 of the report suggests that the deemed return method could immediately raise more tax than adopting the CGT approach depending on the deemed rate of return applied:

Deemed Return Rate for CGT

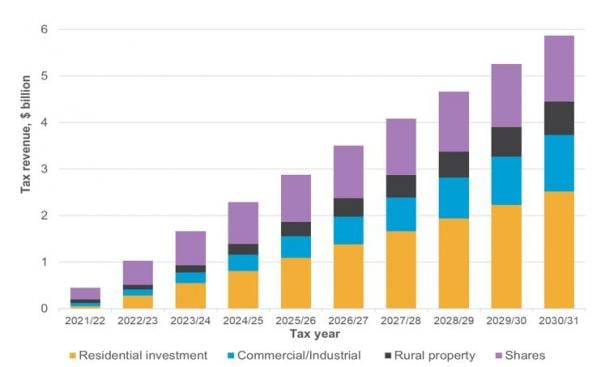

According to the TWG, the projected revenue from a CGT over the first ten years rises from $400 million in the first year to $5.9 billion by 2030/31.

Future Tax Revenues estimate from Capital Gains TaxT

After ten years CGT would represent 1.2% of GDP and a not insignificant 4.2% of total tax revenue.

That raises an interesting point about how a Government might react if a downturn affected tax receipts from CGT. This was a very real problem for California and New York State in particular in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. The deemed return method’s predictability of tax receipts is one reason why it might still be an option.

As noted above the broadening of the taxation of capital income doesn’t replace existing rules such as the FIF and financial arrangements regimes. With regard to the FIF rules, the TWG recommends that the FDR method should be retained. It does consider the present 5% rate should be able to be adjusted frequently as economic conditions change. However, the TWG considers the current ability for individuals and trusts to adopt the alternative comparative value (CV) method if it is lower than FDR as;

“anomalous and inconsistent with the idea behind taxing a risk-free return. It also potentially creates a bias in favour of non-Australasian shares because taxpayers are subject to a maximum 5% rate of return but can elect the actual rate of return if it is lower…. If the FDR rate is ultimately lowered from 5%, the Group recommends removing the ability to choose to apply the CV option only in years where shares have returned less than 5%”

Such a move would increase the tax payable by individual investors unless the FDR rate was set at a level which was fiscally neutral. But it highlights the complexity which will still remain if a CGT approach is adopted.

Volume II of the report has the design details of the proposed CGT.

Two areas of the design have provoked a fair amount of commentary, the treatment of inflation and the proposed valuation day approach.

At first sight the criticism regarding the proposal to adjust for inflation seems reasonable. But as the interim report noted the tax system doesn’t adjust for inflation generally at the moment. Furthermore, as Cullen noted at the briefing the amount taxed under a CGT approach is often lower than that payable under an annual accrual-based approach.

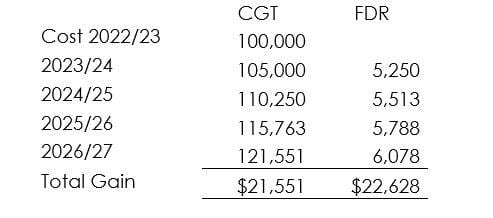

For example, compare the totals taxable between a CGT approach and under the foreign investment fund fair dividend rate method. Assuming $100,000 is invested, which grows at 5% per annum and is sold after four years under CGT, the taxable gain will be $21,551. This is less than the total of $22,628 taxed under the FDR method (generally no income is taxed under FDR in the year of acquisition).

Capital Gains Tax versus Fair Dividend Rate

The TWG proposes that under the CGT approach only gains arising from the date of implementation will be taxed, the so-called “Valuation Day” method which both Canada and South Africa adopted when they introduced their respective CGT regimes.

The potential compliance costs involved have been criticised so the TWG proposes taxpayers should have five years from implementation (or to the time of sale if that is earlier) to determine a value. They also suggest a couple of default methods for assets held on Valuation Day. These are either the straight-line basis or the median method, helpfully illustrated below.

John purchased a small trucking business on 1 April 2015 for $200,000. On 31 March 2025, John sells the business to Paul for $600,000 (i.e. a $400,000 gain).

As a result of the extension of the taxation of capital gains, John will have to pay tax on the capital gain he has derived since Valuation Day (1 April 2021) from the sale of the business (i.e. for the last four years he has owned the business).

Applying a straight-line approach, John will have to pay tax on 4/10th of the gain on sale (i.e. $160,000).

Example business valuation and CGT

The median rule determines the deductible cost as the median or middle value of actual cost (including improvement costs), the value on Valuation Day, plus improvement costs, and the sale price.

In 2014 Scott bought a rental property for $500,000. On Valuation Day the property was valued at $450,000. Scott sold the property six years after Valuation Day for $850,000.

Applying the median rule:

Cost = $500,000

Valuation Day value = $450,000

Sale price = $850,000

The median value is $500,000. Therefore, Scott is able to deduct $500,000 from the sale price of $850,000, giving rise to a $350,000 taxable gain.

Without the median rule, Scott would have a taxable gain of $400,000 (i.e. sale price of $850,000 – price on Valuation Day of $450,000) despite only making a gain of $350,000 over the whole period he owned the property.

There is, as you’d expect, a wealth of detail in these proposals including some anti-avoidance provisions to prevent “bed and breakfasting” as a means of accessing losses. Some losses will be ring-fenced but in general most capital losses should be able to be offset against other income.

There’s plenty more elsewhere to consider in the report such as the proposals for KiwiSaver and the surprising suggestion that the Government “give favourable consideration” to exempting the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from tax. I’ll cover these and other snippets separately.

This post first appeared on Interest.co.nz