- A quiet week in the tax world – but is this the calm before the storm of this year’s Budget?

- The latest OECD report on taxing wages shows the tax wedge rising in most countries including New Zealand.

It’s been a quiet week in the tax world, which, to be honest, is quite welcome. But there’s also a growing sense of a calm before the storm, that being the Coalition government’s first Budget on 30th May, I’ll offer up some speculation as to what I think will be in the budget closer to the time, but one thing we do know will be expected to happen, is adjustments to the flat tax thresholds, which as listeners will well be aware of, have not actually been adjusted since October 2010.

It so happened last week the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (the OECD) released Taxing Wages 2024, its annual Taxing Wages report. This is a fascinating document which looks across the composition of wages and provides details of taxes paid on wages. This year, it’s also focusing on fiscal incentives for second earners in the OECD and how tax policy might contribute to gender outcome gaps and labour out market outcomes. It’s a big report which runs to 679 pages and is only available online.

Taxes are increasing thanks to inflation

One of the things that comes out of the Executive Summary was that in the words of the report tax systems in the OECD are not fully adjusting to inflation. Consequently,

“The average tax wedge for all eight household types covered in this report increased in the majority of countries between 2022. And 2023 driven in most cases by higher income tax. For the second consecutive year, more post tax incomes at the average wage level declined across the majority of all OECD countries now.”

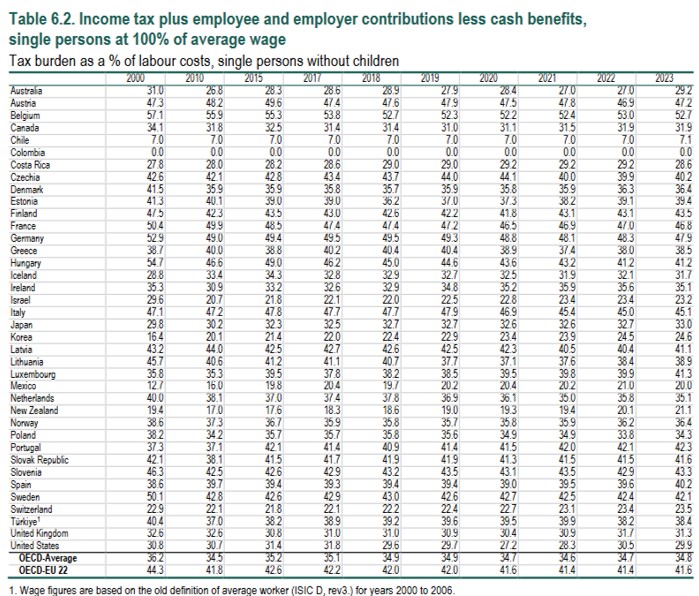

The tax wedge is described as the difference between the labour costs to an employer and the corresponding net take home pay of the employee. It represents the sum of the total personal income tax and Social Security contributions paid by employees and employers. Less any cash benefits that the employee might receive.

New Zealand has consistently scored well in this measure because we don’t have Social Security taxes and we’ll talk a little bit more about that later. But notwithstanding that, the average take home wage for New Zealand employees has been declining over the past few years.

The report has an appendix showing the evolution of effective tax rates on labour since 2000 with a number of separate measurements based on single persons, single parents, or married couple with two children. It looks at what the tax wedge for each group is based on 67% of average wage, 100% of average wage and 167% of the average wage.

Now, whatever measure you take, you can see that the tax burden for New Zealand employees has been rising steadily since 2010, but you can see it start to accelerate in the last three to four years. So, for a single person at 167% of the average wage, their tax burden has gone from 23.9% in 2017 to 25.8% in 2024. Now you might think 2 percentage points isn’t much, but it becomes more noticeable as it accumulates over time. For a single person at 100% of the average wage the tax burden has gone from 18.3% to 21.1% over the same period.

This OECD report reinforces what we’ve been saying for some time that tax adjustments to the thresholds are long overdue. Now those who listened in to last week’s podcast with Sir Rob, Rob McLeod, Robin Oliver and Geof Nightingale will have noted pretty much everyone was of the view that the threshold where the 30% tax rate kicks in, that’s $48,000 was a major problem in our tax system. Geof was particularly insistent on this point. This OECD data reinforces that point. So, it will be interesting to see what moves are made in that space in the Budget at the end of the month.

Social security taxes – time for a rethink?

Moving on, thanks to everyone who’s commented or given feedback here and across the various social media platforms about last week’s podcast. It’s always great to have some engagement. I do read all the comments even if I don’t always respond.

There were some particularly interesting comments from Dr Andrew Coleman of the University of Otago about Social Security taxes and the absence of them in New Zealand. As he noted, New Zealand is an outlier in world terms in this respect.

Now, as I mentioned in the podcast, Social Security contributions were once quite a significant factor of the New Zealand tax system from the 1930s until the 1960s. But what happened over time was that the contributions weren’t hypothecated and applied only to Social Security payments, but in fact just became treated as part of taxation generally until in April 1964, the Social Security Fund was merged into the Consolidated Fund

Ultimately, the then Finance Minister Robert Muldoon decided in 1968 that separate Social Security contributions were no longer required and merged everything formally into income tax. Since then period, income tax has used to pay for Social Security such as welfare and superannuation.

That’s more than 50 years ago, but as Doctor Coleman pointed out many other countries have Social Security taxes. So, is that something we should consider in more detail? Well, I hope to explore that point in a separate podcast.

Sir Rob McLeod, Robin Oliver and Geof Nightingale on expanding the tax base

[In this part of the podcast I asked Sir Rob, Robin and Geof about the strains New Zealand’s Broad Base Low-Rate approach is experiencing and if a government wanted to raise how would it do so- through a wealth tax, capital gains tax, stamp duties or estate duties, whatever].

Sir Rob Mcleod (RM)

Well, if I can kick off, I’m a huge fan of Broad Base Low-Rate (BBLR). I think it’s got a very simple thrust. It’s as much about pragmatism as it is about technical. I think we need to be careful in my experience with the debate and understanding that a Broad Base Low-Rate system is not one characterised by a myriad of taxes. Some people interpret a myriad of taxes as achieving breadth and therefore fitting with Broad Base Low-Rate. No, my definition of Broad Base Low-Rate is a few taxes with a broad reach. That’s where you get the simplicity. And the income tax and the GST covers most of GDP in the nation.

What does it not touch is the question to ask. You can talk about wealth tax and CGT, capital gains tax, but they’re actually part of the income tax. There’s an overlap between wealth tax, capital gains tax and the income tax. I don’t believe that that gap justifies the kind of emphasis that’s being given to wealth tax and CGT.

Sure, we’ve got some capital gains not taxed, most of them actually are taxed already in the system. The comprehensive capital gains tax I think in that sense is a bit of a misnomer because we do not have comprehensive taxation in the New Zealand system. And if you go and then put wealth taxes on, whether it be land or wealth in general, you are actually doubling up on the income tax. You’ve got an element of double tax in doing that and that takes us back to the starting point, that Broad Base Low-Rate is about identifying the gaps. And there’s bugger all gaps actually left by a broadly designed GST and income tax such as New Zealand has.

And when we go into the debates on specifics around the margins of that base, there are good reasons for arguing about why we shouldn’t have them. So that’s why I think BBLR is there. If you want to get more out of what we’ve got than the broad base of income tax and GST, you’ve got to justify it and you’ve got to start with what percentage of the GDP should be taxed in the first place. With balanced budgets, government spending equals taxation. With a balanced budget, which is kind of where the world wants to be these days.

So, I think recognise that the tax rate for the nation is government spending divided by GDP. And there’s a hell of a lot of benefit from there. So, if you want a tax cut, you’ve got to cut the government spending. It’s the only way to do it. Those various elements I think are very interconnected in the debate around Broad Base Low-Rates.

Geof Nightingale (GN)

I think your question was where would you go to for another 1% of GDP? And I would agree with Rob that it feels to me that 30% of GDP or Government expenditure to GDP at roughly 30% has (that’s our long-run average, it spikes up and down for pandemics and earthquakes and recessions and things) that’s a constraint that I would be quite personally happy for our economy to operate against.

The question is then how you raise that revenue. And I totally support Broad Base Low-Rate. I think it’s effective in practise and 30 years of experience. I think the missing bit still there is our income tax is not as Broad Based as it should be, and I think we do need to extend it into further realised capital gains. So, whether you do that as a separate comprehensive capital gains tax like other countries, or you just change the definition of income, that’s a design feature.

Philosophically, it’s the same thing. It’s just how you get there. Taxing more income through realised capital gains, and then I would recycle that revenue into tax cuts, reductions, initially in the lower marginal rates because that’s where our problems come with high effective marginal tax rates in conjunction with welfare, which leads to productivity and incentives to work and all of that. So I would extend the taxation of capital, recycle the revenue and like Rob aim for 30% government expenditure over GDP.

TB

Robin, you were part of the tax working group, you were one of the three dissenters in 2019. I that still your opinion?

Robin Oliver (RO)

As Rob said and Geof echoed, it’s not a black and white issue. Do you tax capital gains or not? I mean, Michael Cullen kept on trying to make the point, talking about taxing capital income, not capital gains. Everybody ignored it, but he had a point that we do tax capital gains in certain cases and it’s all part of our income tax system and GST anyway. Are there holes in the system where you can efficiently raise more money at low cost? And the big hole, the gap in our system, it came out in the tax working group and all other reports is land.

We are a growing economy, growing population, land rises/increases systematically in value and that produces a lot of income and overall, we don’t tax it. You look at all the data, you know, higher wealth people, predominantly own land. Not all, but predominantly. So OK, should we be taxing land in one form or another? And I’ve got sympathy for that, but you’re going down to the workability. No government will ever tax home ownership. If it does, it will cease to be a government pretty quickly and someone sensible will come in and abolish that tax. So that’s a big hole in any land base. And then you’ve got issues about iwi and their relationship with land. You’ve got farmers.

We used to have a land tax. We had a comprehensive tax in the 1890s and we ended up with a tax just on Queen St commercial property. Everybody else got exemptions over time. I have some sympathy for taxing the increase in the value of land or land in some form which is not taxed now, but the housing, the home ownership stuff. You know, David Caygill, he proposed taxing homeowners. And he got told to back off.

I was working with him on capital gains tax proposal and we officials recommended including home ownership. And we were gobsmacked, totally bewildered when he accepted our recommendation. We expected him not to. And he went off to lose that next election, but probably not for that reason.

Workability matters. Home ownership is off the table. Our problem as a country is we take our savings, we invest it in land, we borrow from Australia, we invest in more land, bid up the price of land. We end up with the same amount of land as we began with – because that doesn’t increase – and heavily in debt to Australian banks. Solving that problem is not easy.

The problem with overinvestment in housing

TB

Yes, it’s a behavioural impact. I had this conversation with an American client yesterday, who because of the fact they have to file U.S. tax returns, they’re subject to capital gains tax. But the FIF regime, he looked at that, and said, well, I can’t invest in stocks so I’m going to look at residential investment property here. That’s really a case of an unintended consequence of a tax.

On the family home, I fully grasp all of that, but is there an argument for saying that there is a limit? Because we build some of the biggest houses in the world. New Zealand houses – new houses, were until quite recently – are the third largest in the OECD. They were nearly getting on for close to 200 square metres.

RO

We like our houses.

TB

So could you say above two and a half million dollars or $5 million, the gain above that – some pro rata, we’re getting into technical details, but there is this thing that you’ve just espoused it perfectly, Robin. That at present we’re encouraged to invest in land and more land and borrow. So, there’s a loss of productivity, that 20% dead weight. There’s got to be a lot of lost productivity because capital is diverted into land rather than elsewhere.

RO

The current group did look at something like that, although it was outside our terms of reference. We were not allowed to even consider the home or the land underneath the home or the sky above the. In terms of reference that we did look at that. The trouble is, a $2,000,000 house is not all that much in Auckland, as Michael Cullen kept on putting out, it was a hell of a lot in Whakatane.

TB

There are 77,000 homes in Auckland worth more than $2,000,000, according to an OIA I got.

RO

Probably one in Whakatane.

GN

There’s a technical solution. If you were going to put all realised capital gains into the tax pot, you give every New Zealander a lifetime exemption, regardless of asset class or description, and that might be $5,000,000 or more, less but and that then shouldn’t distort behaviour. It’s arguably equitable and from a compliance and administration perspective, it would take probably 95% of us out of the of the loop.

RO

And with that 95% of revenue.

GN

Yes, well, maybe not because the assets are weighted towards the top. But anyway, the argument against that was always administrative. It’s very difficult to administer. But with current digitisation and things, I’m not sure those administration and compliance arguments – the integration of the land registers and share registers and things – as strong as it used to be. So, there are theoretical solutions there, but they’re hard to get to the public.

RO

The idea of taxing the person with over $5 million has got a lot of appeal, but it’s not realistic. I always give the example of the idea you can freely tax all these very high wealth individual/ medium wealth individual people. Well, some of those are your medical specialists, your surgeon, your oncologist. And they can go to Australia.

You whack this $5,000,000 tax on their income over a lifetime and off they go to Sydney. So you’re sitting here in New Zealand, you’ve got cancer or something like that, and we’ve got a more equal society, but we have no treatment for cancer. Off to a hospice you go.

GN

That might be the case with a wealth tax, but with an income tax I’m not convinced, Robin. I mean, Rob might be able to comment with direct experience of working in Australia. But labour and consumption taxes in Australia on high earners, medical professionals, they’re pretty tough compared to New Zealand. (TB 45% top rate plus 2% Medicare).I would have thought, but I don’t know what your experience is Rob.

RM

it’s not just Australia, we’re becoming more global, aren’t we? So almost every country is a neighbour of one sort or another these days. The other thing is these people are incentivised to find these loopholes. And having lived, having operated and worked in Australia for six years, they’ve seen wealthy people find loopholes there too. So that that won’t go away.

TB

It’s our job to find them, to be frank.

RM

Yes.

RO

The government legislates for them. You get tax free superannuation in Australia, or 15%. We’ve got to get away from this idea we can tax our wealth. Our problem is, as we’re next to Australia, is Australia becoming wealthier than we are. It’s attracting our nurses, our doctors, our policemen, our police persons and what have you through higher wages. We’ve got to increase our wage level and our productivity, and we don’t do that by sitting around and inventing new taxes.

TB

But do we change the incidence of tax, so that capital gets diverted into more productive areas?

RO

I give you the example of houses. I agree with that.

GN

Our effective marginal tax rates, in those doctors, nurses and policemen, if you go across to Australia and look at those, yes, the incomes are definitely higher 30 or 40%. But I think there’s a tax dynamic in there as well for those people. Because we’re sweating our labour incomes, particularly in those low ends.

Robin has often said this, the worst tax rate we’ve got in New Zealand is the 30% rate at $48,000. Which is huge, it kicks in below the median income. So, I think there’s a tax dynamic in those migrations of doctors, nurses and police as well.

What about inheritance taxes?

TB

The $48,000 threshold is a shocker. A final point on this housing. I think you’re right, politically a capital gains that incorporates the family home is impossible. You’re not even a one term government with that. But does that perhaps point to the need – and this is where the IMF come in – is that maybe that’s picked up through an inheritance tax at a separate point. Inheritance taxes, estate duty used to be quite significant. It was 5% of government revenue way back when in 1949, and they were one of the first taxes we introduced here. But they’ve declined over time around the world, but now there seems to be particularly with this, the wealthiest generation in history – and I think all of us are members of the Boomers – are starting to pass away, and there’s a huge transfer of wealth about to happen. And governments are looking at that.

RM

Can I bring the conversation back to where I was about what percentage of GDP should tax be.

Because we are straight into, in essence, the tapestry of taxes. And what lurks underneath the motive for that conversation is really redistribution. Because a lot of the motive in the conversation that we’re having is about getting feathers off particular geese, and about certain thresholds and the rest of it.

The starting point ultimately is what does the country need by way of revenue as a percentage of GDP now? Now, if you’re arguing that actually New Zealand’s got a big problem of injustice or inequity because the rich are basically getting away with it, is a bit of a different to back from where we came from and earlier on in our conversation. Geof, to be fair, has identified redistribution as a goal. So he’s been consistent in that regard.

But I think this demonstrates why it’s so important to first of all ask yourself what you’re trying to do with your tax system, and if it is about revenue and getting a particular percentage of the GDP, then I think that these debates about estate duty and wealth tax and land tax are red herrings.

The 1% of GDP, for example, Geof, that you’ve mentioned in the question we’re asked to consider through a new tax, does not undermine my general principle of the broad reach and impact of GST and income tax. In fact, you guys (Robin and Geof) were both on the Cullen Review and you actually, in the report that came out, compared a 1% increase in GST with the capital gains tax and it kind of blew it away. That demonstrates my point that the Broad Base reach of GST and income tax can do everything that you’re trying to get out of these, peripheral and miscellaneous taxes. The only thing that’s left standing as to why you want to do it, is redistribution.

RO

I’m OK with that, obviously. But getting on to death duties, estate duties, they have an interesting history. Other countries have them. People have different ideas about bequests and motivation. You know, how important it is to give money to the children. You’ve got Warren Buffett, who honestly gave each of his children 10 million and that’s it. Well, 10 million seems like a nice little nest egg, but in Warren Buffett’s terms, that’s just rounding. Bugger all in bequest terms, Other people will die for it. Literally, they will fight. It is enormously powerful. They will do anything to avoid death duties.

When we used to have them, that was the area of massive tax planning. It was the beginning of it all – avoiding death duties was a massive industry. And you think it’d be easy to do. Well, you’ve got to have gift duties as well, otherwise people just give it away to the kids. And you end up with Inland Revenue, as it used to do, roaring around, stamping every gift that’s made in the country, every Christmas and what have you, and determining they’re not subject to gift duty.

Massive amounts of bureaucracy involved. They are not easy taxes and I’ll just finish with the history of the end of death duties in New Zealand.

It started off with Australia. Death duties were limited to the state governments. When Queensland got rid of its death duties Victoria and New South Wales and the rest of Australia followed suit. We followed thereafter. Because anybody was going to go to the country which didn’t have it.

Death duties have got some appeal to people, I understand the issues. It’s very appealing when people don’t have any bequest, motive to actually tax a windfall gain. The only reason they are working, building their business is for the children and grandchildren. These people will react massively to its reintroduction.

[This is an edited part of the full podcast which readers are encouraged to download and listen to at the link at the top of this page.]

On that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.