- An important working paper from the IMF on the taxation of cryptoassets

- Latest government financial statements show a falling corporate income tax take

Submissions close next Friday on the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2023-24, Multinational Tax, and Remedial Matters) Bill. This is the tax bill introduced alongside the Budget. The bill, as is typical, sets the annual rates for the current year ending 31st March 2024, but also has key provisions relating to the establishment of the legislative basis for the implementation of the Pillar Two international tax proposals at a later date. Separately, there are key provisions for increasing the trustee tax rate from 33% to 39%, with effect from 1st April next year.

The main part of the bill involves preparing the groundwork for the OECD’s Pillar Two multinational tax proposals. These are part of the Global Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) initiative which is intended to introduce a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%. Now, I generally have no involvement with clients that would be affected by these proposals which are targeted at the large multinationals. Most of the clients I deal with on international affairs are much, much smaller scale operations.

But there will be plenty of expert commentary and submissions on this particular bill because it will affect significantly large multinationals, those with international presence and gross turnover exceeding €750 million annually in any two of the preceding four years. It’s a fairly select group. There may be some tweaks as a result of submissions being made, but I would expect this to go through largely unchanged. But it will be interesting to see what submissions are made around this.

Increasing the trustee tax rate – maybe not quite such an obvious move

Of much more direct interest to many more clients and probably also much more controversial is the proposal to raise the trustee tax rate from 33% to 39%.

Now, conceptually aligning the trustee tax rate with the top personal income tax rate makes sense. We see that in other jurisdictions. Practically speaking, however, given the incredibly diverse and prolific nature of trusts in New Zealand, this would seem to be a much more practically difficult issue to implement it.

In discussions with other advisors, a couple of points have emerged. There seems to be a general consensus that some form of de minimis threshold is appropriate to take account of the fact that there are so many more trusts and they have operated on a policy of not generally distributing income because the 33% tax rate probably aligned with most of the income tax rates applicable to most of the beneficiaries. The 39% tax rate only kicks in above $180,000 income and that’s a much smaller group.

The argument which has been raised is that the measure, although conceptually correct, is actually in response to a small group. And therefore, it has a rather indiscriminate effect on people whose aggregate income including that of a trust, would not cross the $180,000 threshold. The suggestion has been made that we should have some form of de minimis threshold. I’ve seen suggestions raising between $15 and $50,000.

In response to this proposal Inland Revenue officials have asked “What’s to stop people setting up a number of trusts to maximise the advantage of the differing thresholds?” Well, two things. One, first of all, practically the cost involved of establishing these trusts, you would typically not get much change out $2-3,000 plus GST. But more importantly, you then have ongoing costs involved because following the Trusts Act 2019 coming into force in early 2021, trustees are much more conscious of their obligations including providing information to beneficiaries.

But more importantly, if someone established ten trusts like that and then divided up assets and income producing assets so as to maximise any potential threshold that would run square head on into Inland Revenue’s existing anti-avoidance provisions. Therefore, in practical terms, I think Inland Revenue’s arguments about the risk aren’t really a starter. There is also the question that there are there are increasing compliance costs involved with running trusts now as I just mentioned.

There’s also something Inland Revenue tends to glide around in my view and that’s its very, very narrow view of Section 6A of the Tax Administration Act. This states Inland Revenue’s duty is to collect the highest amount of revenue that is practicable over time, bearing in mind the costs of compliance. Keeping that in mind some form of de minimis seems a not reasonable approach. Otherwise, trustees may feel that they are obliged to do a load of distributions to beneficiaries just to minimise the tax payable.

I have actually encountered scenarios where trusts were established which could have done that and minimise the tax payable but didn’t do so for a variety of reasons. So it could be that inadvertently Inland Revenue may trigger the trustees to actually distribute income at lower tax rates than they were doing previously. I’m certainly watching to see how the Select Committee responds to this point.

Deceased estates potentially unfairly penalised?

The second point about the 39% tax rate increase is how it will apply to estates of deceased persons. The proposal is the 39% rate will apply to a deceased estate after 12 months have passed since the person died. Now, my immediate reaction to that proposal when I read it was that period was way too short, and that has been confirmed in subsequent discussions with other tax practitioners and lawyers. In fact, right now I’m involved with the tax affairs of an estate where more than three years has passed since the death of the deceased person.

The majority view of the lawyers I’ve spoken to on the matter is the minimum period should be at least 24 months and probably somewhere between 36 and 48 months would be much more realistic. I would be interested to see what happens here; particularly about just how many law firms do make submissions on this. I’ve made the law firms I work with aware of the issue and recommend they do submit. Select committees sometimes hear a lot from the same people, but they are always particularly interested in hearing from people who don’t normally submit but are doing so in this case on the practical basis “Our experience is this would be not a good move” or “We would support it”, whatever.

Anyway, submissions on this bill close next Friday. If you have concerns about any of these measures I’ve discussed, make a submission to the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee using this link.

The IMF holds forth on cryptocurrencies

Now moving on, this week the International Monetary Fund, the IMF, released a working paper on the taxation of crypto currencies. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/06/30/Taxing-Cryptoc… This is an absolutely fascinating paper, it’s actually one of the most interesting papers on the taxation of cryptocurrencies than I have seen since crypto assets moved into the mainstream over the last five years.

In short, the IMF’s view is that tax systems need updating to handle the challenges posed by crypto assets, particularly in relation to their anonymity and their decentralised nature. And these, in the IMF’s view, make it hard to establish and maintain effective third-party reporting systems such as we use here in the banks or the international OECD’s Common Reporting Standards on the Automatic Exchange of Information.

It’s a very readable paper which starts by pointing out that after basically starting from zero in 2008, the market value of crypto assets peaked in November 2021 at about USD3 trillion USD (nearly NZD5 trillion). Although estimates vary because the surveys are self-selected, maybe perhaps 20% of the adult population in the U.S. and 10% of the adults in the U.K. hold or have held crypto assets. And the number of global users could be as many as 400 million people. On the other hand, although USD3 trillion sounds like a lot, it’s only about 3% of the global value of equities.

But the paper notes the potential for disruption, which is one of the founding ethos of Bitcoin and the crypto asset world, is quite significant. There are all sorts of questions around the tax impact of all these colossal capital gains suddenly arising and then the potential impact of losses, now that USD 3 trillion valuation is down to around $1 trillion. What’s going to happen with those $2 trillion of losses? Are they being claimed?

The paper really is very, very interesting in covering a whole number of topics. And basically it sums up the problem as being tax systems were not designed for a world in which assets could be traded and transactions completed in anything other than national currencies. It has some interesting comments about the effect of crypto billionaires. Apparently 19 were on the Forbes list, the richest list in America in April 2022. In an interesting aside the paper comments about “a loosely defined sense that much wealth channelled into crypto escapes proper taxation appears to have become part of the wider mood of dissatisfaction around the taxation of the rich.”

Blockchain efficiencies for tax administrations?

Yes, there are certainly crypto billionaires, but a lot of ordinary people probably piled into crypto because they saw an opportunity to realise substantial gains. How they declare those is of course where this paper is focussed on. It also notes that much is made of blockchain technology and it the working paper notes that the information blockchains contain on the history of transactions is actually remarkably transparent which

“might ultimately prove valuable for tax administration; and the use of smart contracts (self-executing programs) within blockchains, for example, might in principle help secure chains of VAT compliance and enforce withholding.”

What this paper picks up on is concerns I haven’t seen too much discussion of around the VAT (value added tax) or GST consequences of transactions using crypto. The paper’s section on externalities picks up on an issue which has is often raised in relation to crypto, and that’s the carbon effect of mining. It notes that the associated carbon emissions are cause for considerable concern including an estimate that in 2021 Bitcoin and Ethereum mining used more electricity than either Bangladesh or Belgium and were responsible for generating 0.28% of global greenhouse gas emissions. It suggests there maybe should be a charge on mining in relation to that effect.

Overall, the paper does not propose solutions. It is a working paper which is really raising all the issues. Now, it notes which I’ve mentioned recently, that the OECD has introduced its Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework, which is to extend the Common Reporting Standards reporting to the crypto world. But in the IMF’s view, “implementation remains some way in the future and in any case will not in itself resolve the issues challenges proposal posed by decentralised trading.”

Overall, a very comprehensive and readable paper which brings a big picture thinking to the issues the taxation of crypto crypto presents. I highly recommend reading it.

Government tax revenue behind forecast

And finally this week, the Government released its financial statements for the 11 months to 31st May. Of note immediately was that total tax revenue of $102.8 billion was $2 billion below forecast. Now $1.87 billion of that shortfall related to lower corporate income tax. GST was also $104 million below forecast and also another note that the economy is slowing down.

On the other hand, the rise in interest rates means that the amount of resident withholding tax collected on interest is $242 million ahead of forecast. Incidentally, the withholding taxes on dividends are also $12 million higher than forecast. That latter point may be in reference to what we discussed at the opening of the podcast, with the trustee tax rate rising to 39%, some more dividends are being paid ahead of that rate taking effect.

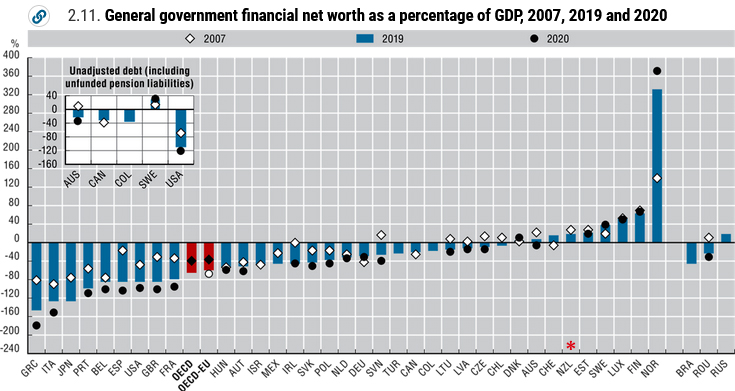

Government core expenses at $145.6 billion were actually $120 million below forecast. Interest costs were just under $6.6 billion, $134 million higher than the Budget estimate. Overall, the government debt rose by $5.1 billion to $73.3 billion, but net that’s the equivalent of 18.9% of GDP. The Government is still in the black. Overall, based on 2021 numbers, its net worth of $170.4 billion, which is roughly 44% of GDP, keeps it as one of the few OECD countries with a positive net worth.

There’ll be plenty of talk about budget deficits, etc. going forward in the election campaign. And we’ll be paying attention to what the parties say on tax. But it’s probably just worthwhile keeping it in context that the Government’s balance sheet is reasonably solid. You wouldn’t want it to be running away rapidly, but when you look at what’s going on in the United States where they basically cobbled together ad lib budgets to just paper over the cracks until the next crisis emerges, we are in a reasonably strong position.

How that balance sheet is maintained and used to brace ourselves for the impact of climate change is a major challenge. I think we now have a major issue in terms of having to basically fund adaptation by having to fund moving people out of at-risk areas. Cyclone Gabrielle rendered 700 homes unliveable. That could add up to maybe a billion dollars. Although a billion dollars in the context of $145 billion government spending is well under 1%, a billion dollars year in, year out is money that is not going into other areas that people want for health, education, etc. So anyway, the Government’s books are in reasonably good shape, but there are strains ahead.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.