- A look at the abandoned proposals in the recent Budget for a wealth tax and tax free threshold as part of a tax switch

- Inland Revenue comes under fire for its lack of tax investigations

The big news last week was the release of the official advice to Ministers on tax incentives during the lead up to this year’s Budget. And it was quite a bombshell. Amongst the wealth of material provided was the surprising news that a key proposal had been until quite late in the piece a tax switch where in exchange for introducing a tax free threshold of $10,000, the Government would introduce a wealth tax.

Now, the Prime Minister immediately ruled out the wealth tax and also ruled out any capital gains tax if the government gets re-elected. So to a large extent, all this fascinating material is largely redundant. But it still provoked the continuing debate around the pros and cons of a wealth tax. And in fact, it’s really very interesting to go through the material and see how the policy developed and where they were planning to take it.

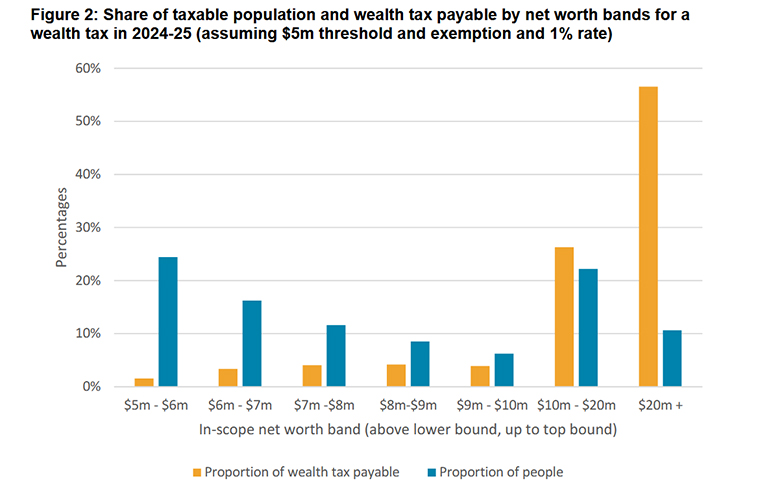

The final scheme would have applied a 1% tax rate to net wealth above a $5 million threshold under what was termed an “exemption approach”. This was initially thought it could raise between $2.7 and $2.9 billion annually and would have affected some 46,000 individuals. According to officials the wealth in scope at a $5 million threshold would be about $210 billion

A minimum tax?

Now, in the course of development the proposal started with something called a “minimum tax” under which proposal a person with high wealth would pay tax on the greater amount of either their deemed income calculated as a percentage of the net worth or the taxable income they have under existing income tax rules. The deemed income would have been based on the idea of economic income, which would include unrealised gains. If you recall when the Sapere report and the Inland Revenue High Wealth Individual research project were released, there was a great deal of controversy around this measurement because once you measured economic income and unrealised gains, it appeared the wealthy were paying an effective tax rate of 9%.

This minimum tax was the initial proposal which then got dropped over time. In the course of discussions, they moved away from what they called a “switch approach”. Under this once a person crossed the threshold, then all the deemed economic income would be subject to the wealth tax rather than just the proportion above the threshold.

And this so-called “exemption” is pretty much what we see in other wealth taxes around the world. It appears in the design of the wealth tax officials took a close look at the Norwegian system. One of the other features I found surprising was that the family home would be excluded. It seems to me that the tax preferred approach to the family home, has led to a large amount of overinvestment in housing.

Wealth taxes – profile of potential taxpayers

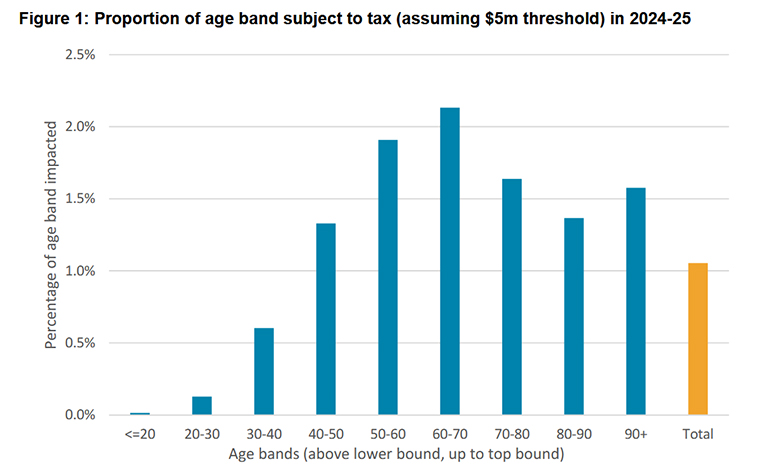

A key report on a wealth tax contained a very interesting discussion, around which group of taxpayers would be most affected. The projection was the age group which would be most affected at the $5 million threshold was that between 60 and 70. An estimated 2.1% of this group population has net worth over $5 million. According to these statistics, 1.5% of the over 90 year old group would be affected.

But in fact, as you might expect, more than half of the wealth tax would have been paid by the high net worth individuals with a net worth in excess of $20 million.

Officials prefer a capital gains tax

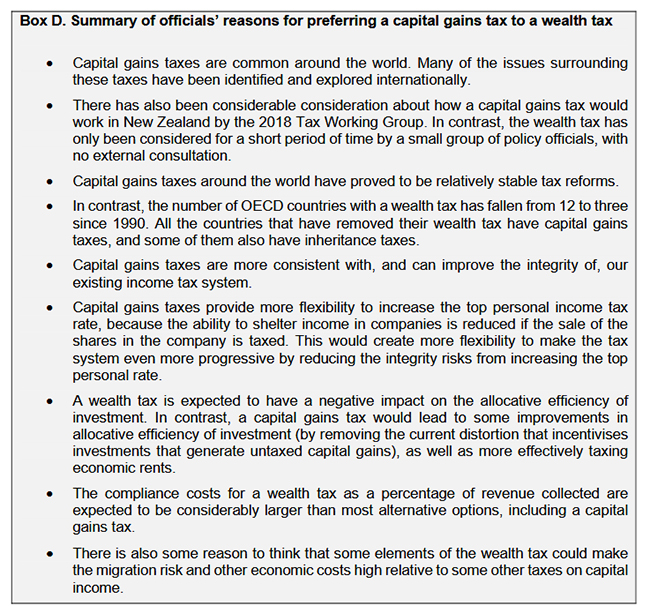

But I think the other thing that came out quite clearly from the papers was that the officials were not at all impressed by wealth taxes. They preferred a capital gains tax.

By the way, the officials view probably reflects a reasonably widely held belief if largely unspoken view amongst the tax community, that if we’re going to tax capital then a capital gains tax is probably the way forward.

Anyway politics intervened again and so a capital gains tax has now been ruled out in their prime ministerial lifetimes by two successive Labour prime ministers. However, as I said to Corin Dann on Morning Report the politicians may rule out capital gains taxes but we’ve got a lot of issues with an ageing demographic and the impact of climate change. The strains on the tax system, which have been recognised by Treasury and its Long Term Insights Briefing He Tirohanga Mokopuna in 2021 recognises that. The issues about needing more tax from somewhere haven’t gone away.

Paying for Cyclone Gabrielle

There were also suggestions as a one-off response to the impact of Cyclone Gabriel, for a levy on the banking sector. There was a comment that the four main banks have persistently “elevated levels of profitability relative to the smaller New Zealand banks and overseas and comparators in part due to the relatively low costs of the large New Zealand banks.” A temporary levy on the banks could raise somewhere between $230 and $700 million. As the Greens noted, Margaret Thatcher of all people did actually impose a surcharge on banking excess banking profits when she was Prime Minister.

There was also a suggestion of a one-off flood levy similar to what was introduced in Queensland following their catastrophic floods in 2010-11. A temporary 1% levy applied to all taxpayers would have raised $1.8 billion. But one only applied to income above $100,000 would raise $250 million.

The quid pro quo – a tax-free threshold

The quid pro quo for a wealth tax would have been a $10,000 tax free threshold. Once again Treasury and Inland Revenue weren’t enthusiastic. They suggested more significant increases in the lower thresholds including lifting the threshold at which the rate goes from 10.5 to 17.5% from $14,000 to $25,000, which is actually substantially ahead of where it would have been if had it been indexed to inflation. However, they proposed lifting the next threshold rate increases to 30% to $52,000. This is the threshold which I think is extremely problematical because of the large jump and at its current level of $48,000 is now well below both average and median wages.

There are two things of interest here. Firstly, a recognition that something has to be done. Tax free thresholds are very popular, but they’re not as efficient is the official advice. Secondly the cost of increasing these thresholds would have been over $4 billion annually. This is an acknowledgement that by not indexing thresholds since 2010, governments have given themselves a permanent headache around having to make threshold adjustments that become increasingly expensive.

A mystery policy?

A tax-free threshold is apparently out of the question. But maybe not because amidst all the papers, there’s are parts which have been redacted. These refer to another policy, whether that was capital gains tax, we don’t know. But whatever it was, it’s been redacted and not been released under the Official Information Act.

We’re now within three months of the General Election and Labour is still to release its tax policy. So maybe there’s something in that hidden part which will be revealed.

Secrecy and the Generic Tax Policy Process

There’s been some discussion that because this was all carried out secretly and outside the Generic Tax Policy Process (GTPP) that maybe this might not have resulted in a terribly efficient tax. I’m less concerned about governments deciding they’re going to do something for electoral gain and requesting work be carried out discreetly. But I do agree that if it’s done outside the GTPP, there is a risk that the design could be faulty. We’ve seen that with the bright-line test and the continual tinkering that has to be done. Worth remembering, by the way, that the bright-line test itself was a surprise. There was no previous consultation before it was first introduced in the May 2015 Budget by Bill English.

I like tax surprises in budgets, and I believe they’re part of normal politics. As I’ve said before, tax IS politics. But I do think that if you look entirely at tax through a political lens, then you start to get this narrow view developing right now where everyone says the politics of raising taxes are too hard, but the economic question of, how are we going to pay for the coming challenges just gets sidelined.

To repeat myself, we have serious issues to address coming up. And my view is if you want to maintain the broad based, low rate approach to fund these challenges, you’re going to have to do something around capital taxation. And the sooner you do it, the better.

Inland Revenue dropping the ball on investigations?

Moving on, one of the officials’ key objections to a wealth tax was the cost of compliance. Inland Revenue would clearly need to increase its capabilities. In its advice on its Initiative Work Programme it commented “the Government’s current tax and social policy work programme will use up most of our specialist design and delivery capacity over the next three years.”

Now the question of Inland Revenue’s operational capabilities came up at the start of last week when it was raised by National’s revenue spokesperson Andrew Bayly.

Following some written questions to the Minister of Revenue, he had determined that the number of investigations conducted by Inland Revenue dropped from an average of 77 a month between February 2017 and October 2020 to only 17 a month between October 2020 and June 2022. Furthermore, the time Inland Revenue spent on hidden economy investigations has also dropped substantially, from 3094 hours in November 2020 to just 805 hours in May this year.

Mr Bayly thinks Inland Revenue is dropping the ball here. Now, he’s tried that for obvious political reasons to Inland Revenue’s work on the High Wealth Individual research project, but that was separately funded. (Incidentally, early drafts of the report were made available to Cabinet as part of the pre-budget preliminaries).

There is an ongoing operational issue, in my view, about Inland Revenue’s investigations activity. And actually, it has acknowledged it has not been doing as much work in the investigations and debt recovery field. Page 36 of its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2022 notes:

“We did less work than would be typical in areas such as debt collection, investigations, disputes, litigation and liquidation activity.”

Now, part of this is down to the response to COVID. There were great demands made of Inland Revenue to which it responded superbly. But note the number of investigation hours back in November 2020, which is in the heart of the pandemic, was 3,094 but now it’s down to only 805 hours when we’re supposedly post pandemic, or rather a different stage of response to it. Inland Revenue saying that the fall off in investigations is because it has had to deal with COVID and this year’s weather-related events is not a satisfactory explanation in my view.

And when you start digging into Inland Revenue’s appropriation statements which are published as part of its annual report, you can see the amount spent on investigations for the past five years has fallen quite considerably in absolute terms, let alone when adjusted for the impact of inflation.

Reduced investigation funding

In the year to June 2018, the investigations appropriation was just over $140 million. But for the year to June 2022, it was just over $113 million. That’s a significant drop of nearly 20% in absolute terms.

Inland Revenue investigations appropriation per annual reports.

30 June 2022 $113.235 million

30 June 2021 $124.325 million

30 June 2020 $109.720 million

30 June 2019 $134.706 million

30 June 2018 $140.164 million

So, what this points to is the claims being made by Mr Bayly about Inland Revenue taking its eye off the investigations ball does appear to be backed up by the evidence of where it’s been spending its money. One of the explanations for this appears to be tied into its massive Business Transformation project. Inland Revenue, once it got started on this, seems to have pretty much solely focused on getting it across the line.

Where did the investigations staff go?

Part of Business Transformation included substantial reductions in its headcount, which went from 5789 in June 2016 to 3923 in June 2022. Now, that’s nearly a third of the workforce gone. We also know that although there was a substantial number of staff (nearly 800 apparently) whose sole purpose was simply re-inputting data so it could be used, a large number of very experienced investigation and operational staff were also let go. I know that because I’ve been speaking to a few of them.

Therefore, other tax advisers and agents and I are wondering whether Inland Revenue now has a diminished Investigation capability. There’s also another matter which Andrew Bayly also picked up on, the fact that Inland Revenue has decided to adopt a completely new metric for measuring its investigation performance. That makes you wonder why it’s done that. We won’t know what they’re measuring and how effectively, as the year just ended on 30th June is the baseline for this new metric.

But it’s important in a system that relies on voluntary compliance, there is the expectation by all of those taxpayers who comply that Inland Revenue is making sure that those who are not playing by the rules will be found and investigated. The concern is if Inland Revenue’s capacity to do that is diminished and it’s not fulfilling that role, then the overall perception of the integrity of the tax system is undermined. And that’s not good long term because naturally people will start thinking “That person is getting away with it, so we can too”.

I hope this is something the new Commissioner of Inland Revenue Peter Mersi is paying a lot of attention to. It will be very interesting to see what the department says when its latest annual report is published in October.

Inland Revenue renews its focus on GST

And finally, this week and, coincidentally or not, a couple of days after the story about Inland Revenue’s lack of investigation focus, it posted a warning for tax agents about “Its renewed focus on GST compliance”

Now, you can easily interpret this as an implicit acknowledgement of Andrew Bayly’s criticisms, but it is in fact another sign which we’ve seen steadily emerging that Inland Revenue is now repositioning itself back into what you might call its regular routine.

As usual, we’ll keep an eye on what that means and bring you developments as they emerge.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.