Although intertwined with the issue of capital gains, finding a fairer treatment for retirement savings is arguably the most important objective for the TWG, says Terry Baucher

Rather like Dug in Up almost all the commentary around the Tax Working Group’s (TWG) interim reporthas chased the squirrel of capital gains tax (CGT).

Although probably inevitable, the focus on CGT risks overlooking some of the other issues analysed in what is probably the most comprehensive overview of New Zealand’s tax system in nearly thirty years. These other issues would include land tax, GST and retirement savings.

Although a final decision on the optimum approach to taxing capital gains will wait until the TWG’s final report next February, the Government has accepted that the TWG need not carry out further analysis of areas such as wealth tax, land tax, changes to New Zealand’s petroleum and minerals royalty regimes, GST coverage and a financial transactions tax.

I am very surprised that a land tax is completely off the table, particularly after the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group came out strongly in favour of it in 2010. Reading between the lines, the TWG appears to have decided the politics of a land tax are even more difficult than those around a CGT. Conversely, given the general tenor of the TWG’s comments on the issue of taxing capital, removing the land tax option probably increases the likelihood of either a CGT or taxing capital based on a risk-free rate of return being recommended.

No change for GST

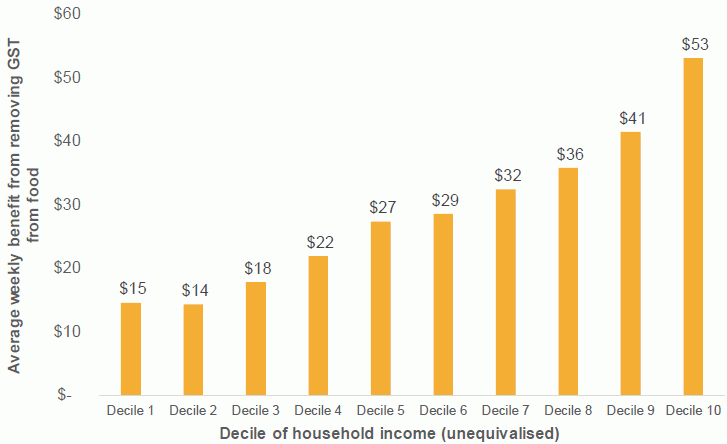

On the other hand it is no surprise that the TWG isn’t recommending changes to the current GST framework. The arguments for exempting food from GST are pretty comprehensively demolished by the following graph illustrating the average weekly benefit for each income decile resulting from removing GST from food:

In order to achieve this benefit, the TWG estimates an exception for food and drink would reduce the GST take by $2.6 billion. As the group notes, if that amount was instead redistributed, each household would receive $28.85 per week, or practically double the benefit of a GST exemption for the lowest two deciles. As the TWG concluded other measures than an exemption, such as welfare transfers, would be likely to produce greater benefits for the same cost.

This point is also borne out when considering an alternative measure, an across the board cut in GST from 15% to 13.5% costing $2 billion annually. The result was indentical to that for introducing a GST exception; there were significantly greater benefits to households in the highest income decile.

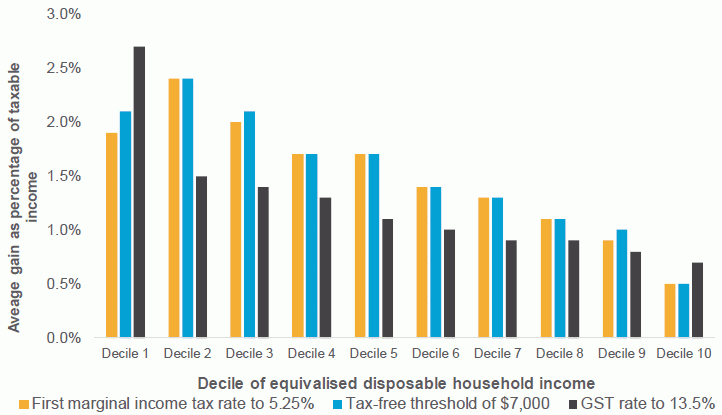

The TWG then compared a GST rate reduction with two alternative measures: a tax-free threshold of $7,000 and halving the lowest tax rate from 10.5% to 5.25%.

The conclusion was that based on percentage of income, reducing the GST rate to 13.5% would provide greater benefits to households in the lowest income decile when compared with the suggested income tax changes. However, there were fewer benefits for households in deciles 2-9 and households in the highest income decile would be the biggest winners.

The TWG therefore decided against recommending a reduction in GST rates, suggesting instead:

“If the Government wishes to improve incomes for very low-income households, the best means of doing so will be through welfare transfers.

If the Government wishes to improve incomes for certain groups of low to middle income earners, such as full-time workers on the minimum wage, then changes to make personal income taxes more progressive may be a better option.”

As part of its review the TWG looked at whether financial services such as bank fees should be brought within GST and eventually determined “there are no obviously feasible options for doing so.” Instead, the TWG proposes the Government should monitor international developments.

The TWG also dealt briskly with the idea of a financial transactions tax (or Tobin tax) on tax on the purchase, sale, or transfer of financial instruments. This was proposed by ‘many submitters’ on the basis of improving market stability and discouraging speculative trading. The TWG concluded:

“The revenue potential of a financial transactions tax in New Zealand is likely to be limited, due to the ease with which the tax could be avoided by relocating activity to Australian financial markets…A financial transactions tax is an inefficient tax that is unlikely to raise significant revenue for New Zealand.”

The door isn’t completely shut on a financial transactions tax, with the TWG recommending the ongoing international debate on the issue be monitored.

Changes ahead for KiwiSavers?

In many ways it’s appropriate Sir Michael Cullen is chair of the TWG as his imprint lies directly and indirectly across the current treatment of retirement saving. Sir Michael was part of the Fourth Labour Government’s radical overhaul of savings in the late 1980s which adopted the present Taxed – Taxed – Exempt’ (TTE) basis for retirement savings. In 2007 as Finance Minister in the Fifth Labour Government he introduced KiwiSaver and the Portfolio Investment Entity (PIE) tax regime. Both, were, more than a little ironically, measures aimed at redressing some of the issues which emerged in the wake of the adoption of the TTE regime.

The report’s review of KiwiSaver begins with an interesting analysis of the impact of inflation on taxation. The report observes:

“Although inflation is currently low, nominal interest rates are also low; this has made inflation a larger component of the nominal interest rate and therefore increased the real effective tax rate on debt.”

The effect of inflation is illustrated in the following table:

| Table 7.2: The future value of $1,000 invested today after 30 years | |||||

| No tax | Tax real income | Tax nominal income | |||

| 17.5% | 28% | 17.5% | 28% | ||

| Future value of $1000 in 30 years | $4,322 | $3,719 | $3,396 | $3,362 | $2,889 |

| Effective tax rate on nominal income | N/A | 10.5% | 16.8% | 17.5% | 28% |

| Effective tax rate on real income (after taking account of inflation) |

N/A | 17.5% | 28% | 29.2% | 46.7% |

The report concludes that the member tax credit offsets the impact of taxing nominal income for KiwiSaver members earning up to approximately $100,000 per annum. Above that level of income the member tax credit’s effectiveness diminishes.

As the TWG report notes the TTE basis of taxation was, and remains, a significant divergence from the ‘Exempt – Exempt – Taxed’ (EET) basis common in many OECD countries. However, reverting to EET would be a very expensive move: the report estimates the annual fiscal cost of doing so would be at least $2.5 billion initially.

Even with strict limits on contributions most of the tax benefits of moving to an EET system would flow through to high-income earners. The TWG, rightly in my view, considers there is “little value in providing incentives to high income-earners, who are likely to be saving adequately in any case.” (Part of the reason for high income-earners being better savers is that they are more likely to be property owners).

This background of inflation and the potentially expensive and regressive risks of saving concessions led the TWG to:

“Focus on options that are targeted towards low- and middle-income earners – which, in turn, will disproportionately benefit women (who are more likely than men to be on lower incomes, due to part-time work or time out of the paid workforce for caring responsibilities).”

The TWG’s two main proposals are therefore:

- Remove the Employer Superannuation Contribution Tax (ESCT) on the employer’s matching contribution of 3% of salary to KiwiSaver for members earning up to $48,000 per year; and

- Reduce the lower PIE rates for KiwiSaver funds by five percentage points each.

The ESCT proposal would reverse the change introduced in the 2011 Budget and revert the treatment of employer contributions back to what it was when KiwiSaver was established at an estimated annual cost of $180 million. The reduction in PIE rates for KiwiSaver funds would cost a modest $35 million annually.

The TWG also considered the implications for KiwiSaver funds of taxing gains on New Zealand and Australian shares, a matter raised by National MP Paul Goldsmith in Parliament last week. The measure would impose tax of approximately $15 million per annum for those KiwiSaver members with income below $48,000, far outweighed by the proposed changes.

However, the change would cost approximately $45 million per annum for higher income KiwiSaver members. As a counter to this, the TWG suggests the member tax credit could be increased from its present 50 cents per dollar to 60 cents per dollar at an annual cost of $190 million.

Although intertwined with the issue of capital gains, finding a fairer treatment of retirement savings is arguably the most important objective for the TWG. This is because there are now almost 2.9 million KiwiSaver members, 1.3 million (46%) of whom are under the age of 35.

The sums involved with KiwiSaver are large and growing: in the twelve months to August 2018 employer and employee contributions exceeded $5.4 billion with Member Tax Credits contributing a further $785 million. Employees and employers contributed a record $612 million in August 2018 alone.

The TWG proposals for retirement savings therefore will have a significant impact for a large and growing number of New Zealanders long into the future. The interim TWG proposals are modest but do represent a positive step forward. More than just property owners will be watching and awaiting the TWG’s final recommendations.