4 Apr, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Interest limitation and bright-line test changes now enacted

- Guidance to help find your way through the maze of the financial arrangements rules

- The Australian Budget might give Inland Revenue ideas

Transcript

The Taxation Annual Rates for 2021-22, GST, and Remedial Matters Bill was passed into law earlier this week. This is the bill that contained the controversial interest limitation rules. With the enactment, Inland Revenue have released two special reports, one covering a new option for employers to calculate fringe benefit tax following the rise in the top tax rate to 39%.

The second is on the interest and limitation and additional bright-line test changes and clocks in at 216 pages which gives you a good idea of the complexity of the changes

To recap, although the relevant legislation has only just been enacted, the interest limitation rules have actually been in force since 1st of October last year. Since that date the interest deductions for residential investment property is limited to 75% of the interest paid.

Now, the 75% limitation will apply until 31st March next year, at which point it will reduce to 50% and gradually the amount deductible will decrease until no interest will be deductible from 1st April 2025, unless the property in question qualifies as a new build. The special report goes into these changes in detail and helpfully contains almost 100 examples.

The special report also covers changes to the bright-line test, which was extended with effect from 27th March last year to 10 years. Now the act codifies that change and also includes some rollover relief provisions in new sections CB 6AC and CB 6AF. These enable transactions involving look through companies, transfers to and from look through companies or partnerships, that the bright-line test doesn’t reset the timeline for ownership. There’s also a limited exemption for where a trust transfers property back to a settlor.

Other submitters and I wanted to see expansion of the rollover relief provisions for trusts, but they were not pushed through in this bill. But we should see more in the next tax bill, which will be released around the time of the budget, which by the way will be on Thursday, 19th May. The special report does note that although trust resettlement transactions are not currently covered by the legislation it is intended that rollover relief for some resettlement transactions should be introduced in the next available tax bill.

As I’ve said previously, given the complexity of these rules, I think we can expect to see amendments of a technical nature, and in some cases perhaps quite substantial, coming through in subsequent tax bills. But it’s good that Inland Revenue have made this guidance available with plenty of examples to work through.

Even more complexity

Moving on, the interest limitation rules apply to residential investment property in New Zealand, rental property overseas is excluded from the rules, which means deductions are still available. However, they are subject to the loss ring fencing rules. The whole treatment of residential property has been radically altered in the last three or four years, firstly with the introduction of the loss ring fencing rules and now the interest limitation rules.

With overseas properties, one of the issues that arises is the application of the financial arrangements regime to interest deductions that we claim for overseas mortgages relating to investment property. This is an area which I’ve discussed in the past and in particular, the problem that arises where exchange rate fluctuations on an unrealised basis may trigger income for a taxpayer. This is because the value of the mortgage in New Zealand dollar diminishes and economically, the taxpayer has made a gain at least on paper.

The financial arrangements regime is probably one of the most complex parts of the Income Tax Act. And previously, there hasn’t been a lot of official Inland Revenue guidance that is in a digestible form for your average taxpayer. But fortunately, in recent years, that’s started to change. For example, we had interpretation statement 20/07, which explained the application of financial arrangements rules to foreign currency loans used to finance foreign residential investment property.

We’ve now got a draft interpretation statement out for consultation which explains when people can account for income and expenditure under the financial arrangements rules on a cash basis rather than an accrual basis. This is the exemption available for what are termed “cash basis persons”.

Now this is very handy guidance to see because it walks through the meanings of when a person can be a cash basis person for financial arrangements regime and then the implications if they fall out of it. And it gives examples of that. It also covers the adjustment that’s required when a person ceases to be a cash basis person and must return financial arrangements income on the accrual basis. That is, unrealised gains and losses must be picked up and included in income.

The interpretation statement sets out four steps for determining cash basis person status. Firstly, determine all the financial arrangements held by that person. Secondly, exclude what are termed “excepted financial arrangements”. Thirdly check whether the absolute value of income and expenditure for the income year in question is less than $100,000 AND whether in every day in the income year, the total absolute value of all financial arrangements is $1million or less.

If you get past those, you still may have a problem with the fourth step, the income deferral threshold. This is something that’s not well known and is a real trap for young players. It compares the income and expenditure calculated on a cash basis with what would be the income calculation on accrual basis. If the income deferral between the two is less than $40,000, then you can be a cash basis holder. If not, then you fall into the accrual regime.

Now, as you can imagine, all this is pretty complicated. And although it’s good to see some guidance on this matter, I can’t help but think that we need to step back and wonder whether we are pulling people into the regime, who really shouldn’t be there.

The complexity of these calculations is at times mind numbing and we need to look carefully at the thresholds for cash basis persons which have not been increased in over 20 years. This is yet another example of how the tax system, deliberately or otherwise, ignores the impact of inflation and pulls people into the net, which perhaps they shouldn’t be.

This is particularly true with the volatility of exchange rates at the moment. I’ve frequently seen unrealised exchange gains arise one year only to reverse the following year. Yes, these fluctuations get resolved by the final wash-up calculation (the “base price adjustment”), but it still imposes a high compliance burden for perhaps marginal amounts of extra tax.

This is a real issue for people and one I think merits review. There hasn’t been a review of the financial arrangements rules since 1999 on the basis the rules mostly work pretty well. Notwithstanding that, these thresholds should be increased and how the regime applies to overseas mortgages should be reviewed to determine if they should be part of the regime and if so, can we do something to make the matters more compliance friendly?

The way the regime works, by the way, is you get the bizarre scenario where the sale of the underlying property without which the mortgage wouldn’t exist is often exempt for New Zealand tax purposes. But the foreign exchange gains on the mortgage will be taxable. So that’s conceptually a little bit of a mismatch. Often, by the way, it should be said that you also get the scenario where even if the capital gain is exempt in New Zealand, the gain is often taxed in the country in which the property is situated.

An eye on what the Aussies are doing

And finally, earlier this week, the Australian budget was released. This is a couple of months ahead of the normal, and that’s because there’s a general election coming up, which must be held no later than the end of May. Now, that means that the election result may mean that what’s in this budget may be well reversed by a new government.

But there were a couple of things in here that caught my eye that may not change. The Australian Government, like ours, is grappling with the rapid rises in the cost of living, so it has it has introduced a fuel excise cut. It has also increased the low- and middle-income tax offset for the current year ending on 30 June 2022.

It proposes to increase this tax offset by A$420 for the current year to a maximum of A$1,500 dollars for individuals and A$3,000 for couples. But it’s not going to be available for taxpayers’ incomes over A$126,000. This measure is going to cost the Australian government A$4.1 billion to enact. It’s an example of something we talked about last week, using tax to try and take the pressure off cost of living increases..

A more permanent measure though, and something which we may see here, at least expanded, is that the Australian Tax Office has had its funding for its tax avoidance task force on multinationals, large corporates and high wealth individuals, expanded for a further two years. And it’s been given a total of A$652.6 million to extend the operation out to 30th June 2025.

Now, this taskforce was established in 2016, and undertakes compliance activities targeting multinationals, large public and private groups, trusts and high wealth individuals. The additional funding is expected to increase tax take by A$2.1 billion dollars, pretty much a little bit over a return of three to one for the investment. And for that reason, I expect that funding will stay in place whatever government is in power after the general election.

I also think it’s something Inland Revenue might be looking to see here. We have the high wealth individual project going on at the moment, looking into what wealth there is in New Zealand and how the wealthy hold that wealth and how they structure their tax affairs.

Although it’s a research project I think you could see Inland Revenue getting more funding following that project to investigate the tax practices of the wealthy. So watch this space. And as always, we will bring you developments as they emerge.

Well, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher, and you can find this podcast on my website, www.baucher.tax or wherever you find your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, ka pai te wiki. Have a great week.

28 Mar, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Inland Revenue’s proposal for a big stick to counter top tax rate avoidance

- Potential tax changes make a difference to the cost of living

- What you should do to get ready for tax year end

Transcript

Last week I mentioned that Inland Revenue had released a discussion document, Dividend Integrity and Personal Services Income Attribution, which set out its proposals for measures to limit the ability of individuals to avoid the 39% or 33% personal income tax rate through use of a company structure. This is what we call integrity measures designed to support the integrity of the tax system. In this case, the proposals are to support the objective of the increase in the top tax rate to 39% and to counter attempts to avoid that rate by diverting income through to entities taxed at a lower rate.

Now this paper is pretty detailed and runs to 54 pages. There’s a lot in here which will get tax agents and consultants sitting upright and reading the fine print as in some cases they will be affected directly. It’s actually the first of potentially three tranches in this area. Tranches two and three will consider the question of trust, integrity and company income retention issues, and finally integrity issues with the taxation of portfolio investment income. And the reason for the last one is that portfolio investment entity income is taxed at the maximum prescribed investor rate of 28%, which is undoubtedly attractive to taxpayers with income which is now taxed at the maximum tax rate of 39%.

The Inland Revenue discussion document has three proposals. Firstly, that any sale of shares in the company by the controlling shareholder be treated as giving rise to a dividend for that shareholder to the extent the company and its subsidiaries has retained earnings.

Secondly, companies should be required on a prospective basis, i.e. from a future date, to maintain a record of their available subscribed capital and net capital gains. These can then be more easily and accurately calculated at the time of any share cancellation or liquidation. That’s a relatively uncontroversial proposal.

And thirdly, the so-called “80% one buyer test” for the personal services attribution rule be removed. This one will probably cause a bit of a stir.

The document begins by explaining these measures are required to support the 39% tax rate. There’s a lot of very interesting detail in this discussion, for example it notes that with the top tax rate of 39%, the gap between this and the company tax rate of 28% at 11 percentage points is actually smaller than the gap in most OECD countries.

But then, as the document says, “However, New Zealand is particularly vulnerable to a gap between the company tax rate and the top personal tax rate because of the absence of a general tax on capital gains.”

And so to repeat a long running theme of these podcasts, this lack of coverage of the capital gains has unintended consequences throughout the tax system. And this question of dealing with this arbitrage opportunity between differing tax rates is, in essence, a by-product of that.

As Inland Revenue notes, one answer would be to align the company, personal and trust tax rates. This was the case until 1999, when the rate was 33% for companies, individuals and for trusts. But this ended on 1 April 2000 when the individual top rate went up to 39%. And since then, the company income tax rate has fallen to 28%.

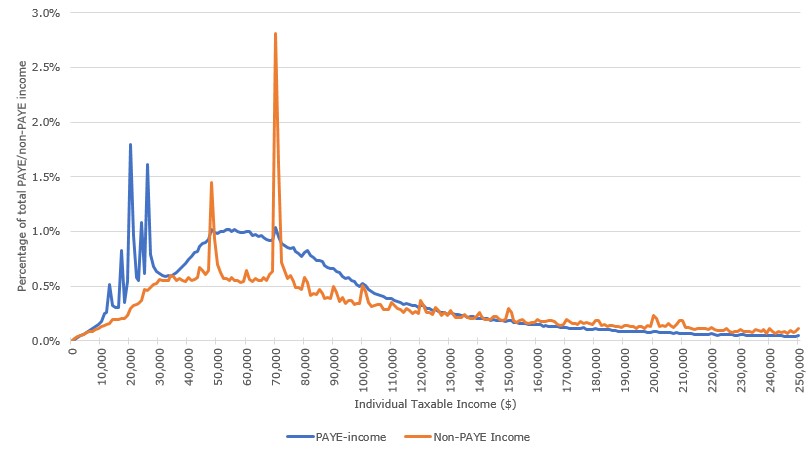

So this is a matter which needs to be addressed. There’s a really interesting graph illustrating the distribution of taxable income and noting there’s a huge spike at around $70,000, where the tax rate rises to 33%.

Taxable income distribution: PAYE and non-PAYE income

(year ended 31 March 2020)

There’s also some interesting data around what high wealth individuals pay in tax. For the 2018 income year, Inland Revenue calculated the 350 richest individuals in New Zealand paid $26 million in tax. Meanwhile the 8,468 companies and 1,867 trusts they controlled, paid a further $639 million and $102 million in tax respectively, indicating a significant amount of income earned through lower rate entities.

It appears to Inland Revenue that tax is being deferred through retention of dividends in companies.

The opportunity in New Zealand is that a sale of the shares under current legislation would bypass the potential liability on distribution. The shareholder is basically able to convert what would be income if it was distributed to him or her, to a capital gain. And clearly, the Government wants to put an end to that, but can’t because it doesn’t have a capital gains tax. The discussion document therefore proposes that any sale of shares in the company will be deemed to give rise to a dividend. This will trigger a tax liability for the shareholder.

The paper goes into detail around this particular issue, and I think this is going to be quite controversial. Because although I could see a measure where a controlling shareholder sells shares to a related party such as, for example, someone holding shares personally sells them to a trust or to a holding company, which they control. You could see straight away that Inland Revenue could counter this by arguing it’s tax avoidance.

But the matter gets more complicated where third parties are involved. And this is where I think the rules are going to cause some consternation because it proposes transactions involving third parties would also be subject to this rule. That, I think is where most pushback will come in on this position. Without getting into a lot of detail on this there could be genuine commercial transactions resulting in some might say is a de facto capital gains tax.

The proposal is not all bad. If a dividend is triggered, then the company will receive a credit to what is called its available subscribed capital, ie, its share capital, which can later be distributed essentially tax free.

In making its proposals, the paper looks at what happens in Australia, the Netherlands and Japan and draws on some ideas from there. It’s interesting to see Inland Revenue looking at overseas examples. All three of those jurisdictions, to my knowledge, have capital gains tax as well, but they still have these integrity measures.

But the key point is this question that any sale, will trigger a dividend. There’s no de-minimis proposed. This could disadvantage a company trying to expand by bringing in new shareholders. It might have to use cash reserves it wants to keep to pay the withholding tax on the deemed dividend. The potentially adverse tax consequences for its shareholders might hinder that expansion. I expect there will be a fair degree of pushback as a lot of thought will go into responding to this proposal. It will be interesting to see exactly what comes back.

Cleaning up tracking accounts

Less controversial and something probably overdue, is the proposal for what they call tracking accounts to cover the question of a company’s available subscribed capital, and the available capital distribution amounts realised from capital gains. Both of these may be distributed tax free either on liquidation or in a share cancellation in the case of available subscribed capital. But the requirement for companies to track this is rather limited, and these are very complicated transactions.

As the paper points out, the definition of ‘available subscribed capital’ runs to 40 subsections and 2820 words. So, there’s a lot of detail to work through, and if companies haven’t kept up their records on this, then confusion may arise if, say, 10 years down the track they’re looking to either liquidate or make a share cancellation.

I don’t see this proposal causing much controversy. I think Inland Revenue’s proposals here are fair and probably something that should have been done a long time ago. They will apply on a prospective basis, as I mentioned earlier on.

Personal services income attribution – a 50% rule?

And then finally, the third part deals with personal services income attribution. And what this part does is picking up the principles from the Penny and Hooper decision. This was the tax case involving two orthopaedic surgeons, which ruled on the tax avoidance issues arising from the last time the tax rate was increased to 39%.

The discussion document is basically trying to codify that decision. The intention is to put an end to people attempting to use what you might call interposed entities, lower rate entities, to avoid paying tax personally. The particular issue it’s driving at is when an individual, referred to as a working person, performs personal services and is associated with an entity, a company usually, that provides those personal services to a third person, the buyer.

Inland Revenue is now looking at a fundamental redesign of this personal service attribution rule, which was designed to capture employment like situations. It was really designed where contractors might be providing services to basically one customer (the ‘80% one buyer rule’) and in effect, they were employees. However, they could potentially avoid tax obligations by making use of an interposed entity with a lower tax rate.

Inland Revenue thinks that 80% rule is too narrow. The proposal is to broaden its application and by doing so it can at the same time deal with the issue that arose with the Penny and Hooper case.

Under current legislation, Bill is an accountant who is the sole employee and shareholder of his company A-plus Accounting Limited. The company pays tax at 28% on income from accounting services provided to clients and pays Bill a salary of $70,000, just below the 33% threshold. Any residual profits are either retained in the company or made available to Bill as loans.

The proposal is to remove that 80% one buyer rule and so that now Bill’s net income for the year, if it exceeds $70,000 will all be attributed to him where 80% of the services sold by that company are provided by Bill. Sole practitioners and smaller accounting firms and tax agents will find themselves in the gun. In fact, the discussion document suggests maybe this threshold of 80% should be lowered to 50%.

Now, you might think that the bigger issue is not the 33% threshold at $70,000, but the $180,000 threshold, so why do we want such a low threshold for this rule to apply? The discussion document points to the evidence that shows that there is income deferral going on. It appears to be at the $70,000 threshold (see the graph above) and wants to put an end to that.

So that’s a more detailed look at what is a very important paper. It’s likely to generate quite a lot of controversy and feedback from accountants and other tax specialists. It’s also another part in the long running tale of the implications of not having a capital gains tax. But certainly, this one will run and run. Submissions are now open and will run through until 29th April. I expect all the major accounting bodies and firms will be responding.

Using tax to mitigate cost of living impacts

Moving on briefly, there’s been a lot to talk about what tax changes could be done to help the increased cost of living. And Daniel Dunkley ran through some of the proposals.

One idea that pops up regularly is the question of removing GST from food. My view, which I expressed to Daniel and is also probably that of most tax specialists, is that this would undermine the integrity of GST, because we don’t have any exemptions on that.

I also don’t think it would achieve the objective that is hoped for. There is, regardless of what people might say, an administrative cost to splitting out tax rates, having zero rate for food and standard rate for other household goods in your shopping trolley. And that differential, that cost involved, will be passed on to customers.

So the full effect of the GST decrease will never flow through to customers. To be perfectly frank; supermarkets and operators will play the margins around this. I suggest you have a look at what’s happened with the fuel excise cut. It was 25 cents, but in every case did the pump price fall by 25 cents? And how could you tell because prices move around so much?

As I said to Daniel, and has been a longstanding view of mine, if the issue is getting money to people who have not enough money, give them more money. The Welfare Expert Advisory Group was staunch when it said that there was a desperate need to raise benefits. We also saw how the temporary JobSeeker rate was increased when COVID first hit. So, this issue of increasing benefits hasn’t gone away.

The best position would not be to tinker with the tax system. You could perhaps look at tax thresholds, definitely, but they still would not be as effective as giving people an extra $30-40 or more cash in hand.

End of year preparations

And finally, the end of the tax year is fast approaching, so there’s plenty of tax issues that you might want to get done before 31st March. A key one to think about is if you’re going to enter the look through company regime, you need to get the election in before the start of the tax year. In some situations you might have more of a bit of a grace period for dropping out of the regime, as part of the Government’s response to the Omicron variant. But it you are electing to join the regime, I suggest you file the election on or before 31st March.

Coming back to companies and shareholders another important issue is the current accounts of the shareholders. You should check to see if any shareholder has an overdrawn current account (that is more drawings than earnings). If so, then either see about paying a dividend or a salary to clear that negative balance, although of course, you’re up against the issue of the higher tax rate I discussed earlier. If that’s not possible, charge interest at the prescribed fringe benefit tax rate of 4.5%.

Companies may have made loan advances to other companies, look at those carefully because you may need to charge interest there to avoid what we call a deemed dividend.

Another very important matter is if there are any bad debts. If so, then consider writing them off before 31st March in order to claim a deduction. And then if you’re thinking about bringing forward expenditure to claim deductions such on depreciation, then do so.

Companies should check their imputation credit accounts balances and make sure these are positive. There are mechanisms through tax pooling to manage this problem if you miss a negative balance.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening, and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, ka pai te wiki, have a great week.

21 Mar, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- The Finance and Expenditure Committee reports back on the tax bill relating to the interest deduction limitation rules

- Inland Revenue releases a swathe of consultation documents relating to GST apportionment, the gig economy & tax avoidance

- New trust reporting standards released

Transcript

If a week is a long time in politics, then the three weeks since our last podcast feels like a decade. If you think I’m exaggerating, Inland Revenue’s latest Agents Answers notes that more than 100 policy and remedial changes are expected to take effect on or before 1st April.

Aside from this, there are also the ongoing COVID support measures. Applications for the second COVID support payment opened on Monday 14th and next Monday 21st of March applications open for a top up loan from the Small Business Cashflow Scheme. In addition, in the wake of the disruption caused by the ongoing Omicron wave, Inland Revenue has effectively delayed the due date for filing March 2021 income year tax returns until 31st May.

This extension also applies to certain elections, which would normally be due by 31st March, and such elections include filing controlled foreign companies and Foreign Investment Fund disclosure forms, making subvention payments relating to the 2021 tax year, and look through company elections for new companies or companies that were previously non-active. That’s all-good stuff and helpful to those tax agents who have been hit by Omicron and their schedules disrupted.

Limiting interest deductions for residential property investors

As I said, it’s been a busy period since our last podcast. The Taxation (Annual Rates for 2021-2022, GST and Remedial Matters) Bill, introduced on 8th September 2021, was reported back to Parliament on 3rd March.

Now this is the bill, which by way of a supplementary order paper, contains the controversial interest limitation and deductibility rules for residential investment property. The bill also has a number of other important measures relating to the treatment of cryptoassets, and GST in particular. It’s an important bill which must be passed by 31st March I believe, as part of the normal Parliamentary supply process.

Cryptoassets are an extremely fast-moving area. As the report of the Finance Expenditure Committee notes, there are already over 15,000 different types of crypto assets. And as a result, the Committee has recommended changes to definitions, in particular, removing the fungibility requirement for the cryptoasset definition. Its now going to add a definition for nonfungible tokens, or NFTs, which are all the rage at the moment.

There was also a recommended change to the GST apportionment rules to make it clearer the new apportionment rules do not target people who are property developers. I’ll talk a bit more about GST apportionment a bit later in the podcast.

But of course, the big and most controversial part of the bill, is in relation to the interest limitation rules. Broadly speaking, there are some changes around the fringes, but nothing significant. And that’s what I would expect with the Government’s super majority. It will push through these changes.

One of the things of note and which will be disappointing to some, is that submissions that the definition of new build should include improving, renovating or repairing existing buildings, dwellings and extensive remediation of uninhabitable dwellings, were not adopted.

The Committee did not consider these to be new builds and should not receive tax incentives by exempting the activities from interest limitation rules. However, the Committee considered the new build exemption should apply in some circumstances where “remediation of an existing dwelling prevents it from falling out of available housing supply.”

The Committee went on “In expanding the exemption, we aim to make these rules as clear and objective as possible, so would avoid using subjective terms such as ‘uninhabitable’.” A wise move there.

They therefore suggest the new build exemption would apply to existing dwellings in two specific situations. These are where a dwelling has been on the earthquake prone buildings register but remediated and removed from the register on or after 27th March 2020, or a leaky home has been substantially, at least 75%, reclad. They say there are verifiable criteria available which would allow for clear application of a new build exemption.

They also have agreed that there needs to be some changes to rollover relief provisions in relation to transfers to and from trusts and parents co-owning property with their children. The later has become particularly controversial with reports in the media about how the bright-line test has affected parents helping their children into a house.

An example given, where parents become co-owners of a property with their adult children and later sell a part share of the property to the children. The parents would be disadvantaged if the period subject to the bright-line test for any remaining share they own restarts on the date of the sale. There’s going to be an amendment to change that.

One of the other things, of course, that happened whilst I was away cycling part of the Tour Aotearoa – highly recommended by the way – is that National made its proposals around changes to the tax thresholds. There’s commentary from the National Party in the Minority Report on the lack of action in that area. And as you might expect, ACT also takes a view that these changes aren’t needed at all. So, politics will carry on as normal

Simplifying GST

Moving on, Inland Revenue has been busy kicking out a number of consultation documents. An important one was on 8th March, which relates to GST apportionment and adjustment rules, which I mentioned earlier. Inland Revenue is looking at policy options for reforming and simplifying these rules.

This is actually very important because these rules are very complex. One concern in particular, is that although GST does not tax most private assets, such as dwellings, an issue arises where some private assets may be used by a GST registered person to make taxable supplies. For example, when a person is working from a home office. Or a GST registered person may own a holiday home, which they also rent out as a taxable supply of guest accommodation.

There is an argument the use and disposal of those private assets may be in the course of furtherance of a registered person’s taxable activity. So that could lead to a GST liability when those assets are sold or an apportionment adjustment if there is a decreased percentage of taxable use.

Now what Inland Revenue have pointed out is, and what’s well known, is that many registered persons are unaware there could be such GST consequences. And what it’s suggesting is that we need to look at proposing a revision of the rules and simplification.

The proposals include a principal payment purpose test for assets purchased for less than $5000 GST exclusive. For assets above that threshold a de minimis test is proposed. If the registered person’s taxable use of the asset is less than 20%, the asset is regarded as non-taxable. No input tax deduction could be claimed on purchase, but critically no GST would be accounted for on a sale. The flipside of this is an 80% rounding up rule. Assets with 80% or more taxable use would be deemed to have 100% full taxable use. So therefore, there would be a full input tax deduction with only small amounts of non-taxable use. This is an important paper and worth reading in detail.

Taxing the gig economy

Another paper which came out two days later, was on the role of digital platforms in the taxation of the gig and sharing economy.

This paper contains proposals intended to make it easier for people earning income through digital platforms, the gig and sharing economy to comply with the tax obligations. It’s looking for feedback on how GST should apply in those rules, and whether there are opportunities to reduce compliance costs in the tax system for people earning in the income from the gig economy. As the paper notes the gig economy is now a substantial and increasing part of the modern economy.

The paper looks at what’s going on and how the current tax system deals with the gig economy. In my view the tax system currently doesn’t deal very well with the micro and small businesses. Just as an aside, in relation to this, I do wonder whether it’s time for the tax system to introduce a nil rate band for income tax purposes. This is something we see in other jurisdictions, for example across the Ditch, in Australia.

As the current legislation stands, every dollar that is earned must be taxed. And I do wonder, that might have been appropriate when inflation was low, but now seems to represent an unnecessary burden, particularly when the rate of tax in the first $14,000 is only 10.5%. The question is how much tax would it cost? How much is involved in calculating that and collecting it? Again, I recommend a good thorough read of this paper.

Minimum standards for trusts

On 7th March, an Order was made setting out the minimum standards for financial statements to be prepared by trusts in relation to new disclosure requirements.

These are actually in force for the current tax year and will be required to be complied with when we start preparing tax returns for the year ended 31st March 2022.

And there’s a special report that sets out what trusts are required to comply and what’s expected to be prepared. Basically, the minimum requirement will be to prepare a statement of profit loss and a statement of financial position. This is part of the wider information gathering that Inland Revenue wants, but also in this particular case on trusts, when you look at the new Trusts Act, which took effect earlier this last year, there’s an expectation for trustees to provide and prepare more financial information.

So again, that’s an effective increase in compliance costs, yes, but also something which is part of a wider need for transparency and full disclosure in the trust regime.

Preventing avoidance of the new top tax rate

Now, if all that wasn’t enough to be chewing over, on Wednesday Inland Revenue released a consultation document on top tax rate avoidance prevention proposals. It’s proposing some measures that limit the ability of individuals to avoid the 39 or 33% personal income tax through use of a company structure.

Now these are what we call integrity measures, there to support the integrity of the tax system. They are to be expected. But what’s interesting here and what’s going to cause some controversy, is a proposal that the sale of shares in a company by a controlling shareholder will be treated as giving rise to a dividend for that shareholder to the extent that the company and its subsidiaries have retained earnings.

This is to counteract the 11-percentage point differential between tax paid at a company level at 28%, and tax paid at the individual level at 39%. What concerns the policy advisers is that companies will not be making distributions of dividends, but by selling the shares and the shareholder usually realising what is a tax-free capital gain under present legislation, this issue of that 11-percentage point differential can be avoided.

Accordingly, one of the measures in this consultation document is to address that. There are a few other matters in the paper which I’m still digesting. So what I propose to do is talk about it at more length next week.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening, and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai te wiki. Have a great week.

21 Feb, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Inland Revenue guidance on the deductibility for income tax purposes of costs incurred due to COVID-19

- Inland Revenue releases an issues paper on the future of tax administration in a digital world

- The tax perils of not taking advice before migrating.

Transcript

We’re now in the third year of the pandemic which over the past two-and a-bit years has resulted in an enormous amount of upheaval, both socially and for businesses. Plenty of unusual situations have arisen as a result, and the tax treatment of those situations needs clarification.

Inland Revenue has therefore released some draft guidance for consultation on the tax deductibility of costs which have specifically arisen because of COVID-19. What the paper notes is that businesses have suffered significant disruption as a result of the pandemic, and many have had to incur additional costs that would normally be regarded as unusual or abnormal, which have only arisen because of the pandemic. In addition, businesses are continuing to incur holding costs such as interest and depreciation for assets which they can’t use at the moment, either because of COVID-19 restrictions or because they’ve temporarily downsized the business.

This paper is designed to give guidance around the income tax deductibility of expenditure in those circumstances. It looks at a number of particular situations that obviously Inland Revenue have seen or have been asked to advise on. For example, what about the costs of bringing employees into New Zealand or retaining teams who are unable to work? What about providing accommodation to keep teams housed together in a bubble during a particular set of COVID-19 restrictions?

Other scenarios include what’s the tax deductibility of giving employees vouchers or incentive payments? And then what about redundancy payments – are they deductible if they were a result of COVID-19? What about costs of terminating contracts and related legal fees?

Repairs and maintenance and depreciation on assets and equipment that aren’t being used because of the pandemic – are they deductible? And then premises costs such as lease break fees and other costs such as keeping people appropriately distanced in a workplace. As you can see, there’s a lot of scenarios considered in the paper.

The general rule for deductibility is in Section DA 1 of the Income Tax Act. For a cost to be deductible there must be a nexus between the cost and the person’s income earning process. Now that’s always a matter of fact and degree and what must be kept in mind is that the cost to be deductible doesn’t need to be linked to a particular item of income and the income doesn’t need to be produced in the same year as the cost was incurred. The cost must be incurred in general terms as part of the business’s income earning operations. That means you can take longer term objectives about why you’re incurring expenditure.

The paper then matches these basic principles to the scenarios that I set out before with a series of good examples. These scenarios involve a hotel chain, a café, a construction company, a tourism business, and an office. I recommend reading the paper if you’ve encountered some of these unusual situations. Consultation, as I said, is open now and continues until 31st March.

Incidentally, talking about consultation, submissions close at the end of this month on an Inland Revenue consultation regarding charities and donee organisations. I covered this consultation in early December and the question of the charitable status of a few organisations has been in the news lately. So, here’s your opportunity to make submissions to Inland Revenue.

Tax in a digital world

Moving on, in my first podcast of the year, I suggested that Inland Revenue will be looking to move forward the process of tax administration now it’s completed its Business Transformation. And I recommended looking at a paper prepared by Business New Zealand on the future of tax administration.

Inland Revenue has now released an official issues paper on tax administration in a digital world. And this, I think, is a very important development for tax administration and for tax agents and intermediaries, or anyone involved in the tax system. As the paper outlines, businesses are moving online, and this is shaping Inland Revenue’s thinking about the future world in which the tax system will operate.

The paper runs to 25 pages and there is a lot to consider so I could rabbit on for quite some time. It picks up many of the principles or ideas that were set out by the Business New Zealand paper, but probably at a higher level. Inland Revenue believes that there are four pillars that set out the core framework for tax administration and social policy administration to function well. That is fairness and integrity, efficiency and effectiveness. And the paper discusses what is the impact of technology on all of those.

As Inland Revenue sees it, key features of the digital world are likely to be businesses operating in a digital ecosystem. That is, connected digitally to their suppliers and customers. The Administration of tax and social policy payments will be integrated to broader economic systems. That means, for example, individuals or businesses can use a common digital identity across a range of services. That is something I think that’s happened with COVID-19. The pandemic will accelerate that trend because it just makes life so much easier for everybody. You’re not having to deal with providing repeat information to different agencies.

Tax administration processes are going to become embedded into business systems that businesses are using. In other words, they’ll use systems that fit their business rather than tax obligations. And then, this is a key one, digital processes will enable data to flow in real time.

This is a point I keep coming back to – the amount of data that’s flying around and Inland Revenue’s access to that data, is increasing all the time. And the speed with which that data is being received and processed is also accelerating. Which means, as I’ve said repeatedly, there are fewer and fewer places to hide from Inland Revenue.

And so this paper looks at what that future might look like and it sets out some frameworks, and sets the scene in the shift to digital. There’s a very important chapter for tax agents, intermediaries and other people who work with Inland Revenue about how it sees these relationships developing. The paper considers the issue of data, how it’s collected, how it’s shared and what statistical data is to be made available on an anonymous basis.

You will know at the moment there’s a lot of controversy going on regarding a high wealth project where Inland Revenue is asking a group of about 400 New Zealanders for detailed information about their wealth. In my view, one of the weaknesses in the New Zealand system for some time has been that we haven’t actually collated a lot of data when we file tax returns. And so compared with other jurisdictions we don’t really have good data on many parts of economic wealth. That project, controversial as it is, addresses this issue. In the future because data can be found and supplied more easily, I think the data requests from agencies and particularly from Inland Revenue will increase.

There’s also talk about publishing debt data. In other words, if someone’s been a bad boy – and by the way, it is invariably boys in my experience – Inland Revenue may share that data and may develop a number of tools for enforcement.

Then the final chapter talks about general simplification process, how tax laws are written, simplifying the tax year end position and payments around the tax system.

The issues of data sharing and data protection are very, very important. In my view Inland Revenue does have a good reputation and processes for not leaking data, and its data is secure. But as it changes its role to interact more with intermediaries such as tax agents, there’s an obvious risk of leakage.

The paper therefore suggests the current process by which a person can become a tax agent needs to change. Actually within the tax agent industry I think there is a recognition that does need to change even if that reflects a certain amount, you might say of self-interest by the professional bodies. It is quite true and not an apocryphal story that a prisoner registered as a tax agent with Inland Revenue when he was in jail. He was able to do so because he had 10 clients who had to file tax returns.

If data is now going to be shared more freely and Inland Revenue is not directly controlling so much of the process, it needs to be certain that the people it’s granting access to its systems or data are trustworthy. So that’s a big issue to consider. As I said, the paper is a fascinating one. It’s a big topic, but it’s only 25 pages, and an easy read. Submissions are now open and continue until 31st March.

The tax consequences of emigrating

And finally, this week, according to the latest statistics New Zealand figures, more people continue to leave New Zealand on a permanent long-term basis than are arriving long term. In 2021, there was a net annual loss of three 3,915 people. Now at the risk of sounding like a broken record, one thing I regularly encounter is this issue of people migrating offshore, usually to Australia, sometimes to Britain or America, and overseas migrants from other countries coming to New Zealand.

It is quite astonishing the number of people who move overseas without looking through and considering all the tax implications of their move. In particular, if they are a trustee of a trust. As I have recounted a number of times, particularly in relation to Australia, the consequences of becoming resident in Australia can be quite disastrous. But I still keep encountering this issue. In fact, at the moment I’ve got three cases on the go involving variations on that theme.

So just a reminder to anyone who’s thinking about moving to Australia or moving overseas. Just remember to get tax advice before you go. You may be missing an opportunity. You may also be giving yourself a significant tax headache, which nobody wants.

Well that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

15 Feb, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Terry Baucher on the latest Inland Revenue guidance on non-resident employers

- calculating foreign tax credits, and

- whether the proposed social insurance scheme could incentivise more honest tax filings

Transcript

We’re now in the third year of the pandemic and one of the things that’s emerged is our working patterns have changed as many people are working remotely, not just from home, but in completely different countries.

This has prompted Inland Revenue to issue an operational statement setting out what would be the obligations for a non-resident employer in relation to pay as you earn, FBT, and employer superannuation contribution tax. This applies where the employer is based in, say, the United States, but the employees are working remotely here. A scenario that I’ve seen quite a number of times in the past couple of years.

Basically, the operational statement confirms that a non-resident employer will have an obligation to withhold PAYE on payments to an employee if the employer has made themselves subject to New Zealand tax law by having a sufficient presence in New Zealand and the services performed by the employee are properly attributable to the employer’s presence in New Zealand.

What that means is if the employer has a trading presence in New Zealand, such as carrying on operations and employing a workforce, that’s normally sufficient for it to have PAYE obligations. And that would be, for example, it has a branch or a permanent establishment. Something always to watch out for is someone is signing contracts in New Zealand and performing those contracts in New Zealand with employees based here for that purpose. But no PAYE obligation arises where the employee decides I’m going to work/ return to New Zealand because it’s safer here, and I can work remotely. That case is not covered.

The paper gives a quick example of an architecture firm based in Boston and one of its employees, George lives in Wellington. George participates in virtual meetings, complete all his work in Wellington. But because the Boston firm has no New Zealand clients, all the work is carried out relates to American work, and the company has no obligation to deduct PAYE.

But what about George’s position here? And this is something that can slip through the details here. In some cases, he is treated as self-employed and pays provisional tax. That’s not technically correct. In fact, what he should do is to register as what they call an IR 56 taxpayer, and he files the employment information and pays PAYE to Inland Revenue. So literally he accounts for his own PAYE. Alternatively, the Boston firm could register as an employer and make the deductions on his behalf.

This is a scenario we’ve seen increasingly, so it’s useful to have some guidance from Inland Revenue in the form of this Operational Statement. It’s also worth pointing out there is also sometimes a double tax agreement applies which allows someone to work in New Zealand for up to 183 days, and there would be no obligation to withhold PAYE.

In addition to PAYE an overseas employer may also find itself with FBT and employer superannuation contribution tax issues if it decides to either voluntarily enter into the PAYE regime, or it has a sufficient presence that deems it to be an employer for PAYE purposes.

The complexities of overseas income

Moving on, it’s getting towards the mad rush for filing the March 2021 tax returns before the final date for tax agents on 31st March. The more complicated income tax returns will often involve overseas income, and Inland Revenue has just issued new guidance in the form of an Interpretation Statement on how to calculate the foreign tax credits that may be involved.

Now, this Interpretation Statement is very helpful because this is a surprisingly complicated topic. There’s a lot of detail involved in this. Firstly, we have to determine is the tax paid, for example, of substantially the same nature as the income tax that we charge. That’s not always the case. Because if the foreign tax is not covered by a double tax agreement and is not of the same nature as income tax imposed under our Act, no credit would be available.

That is something I’ve seen a little bit more of in relation to charges on pension withdrawals made by the UK and Irish governments. They’ve been imposing these charges recently where people have made early withdrawals from pension schemes. The amount imposed can be quite substantial – up to 55% in the case of the UK. The way the charges have been drafted they are outside the double tax agreements we have with the UK and Ireland. And in both cases, that means that there’s no credit for the withdrawal charge. So, a person may face a large charge from either Ireland or the UK and a tax charge here and have no relief for the charges imposed by the Irish and or UK governments. It’s a complicated topic and something to watch out for.

The first booby trap you have to watch carefully where a double tax agreement is involved is what the limits are and whether New Zealand actually has any taxing rights in relation to that income. That’s not always the case. But even when you get past those two positions in terms of calculating the credit, you then have to break it down into segments. They must be divided by country and then by type.

If you’ve had tax deducted of 20% from US sourced income and 10% from UK sourced income, you cannot just aggregate those two amounts and offset them against a single amount of overseas income that you report on your return. You have to actually break it down further than that by country and by type of income. And if you’ve got an attributing interest in a foreign investment fund income, that’s a separate calculation as well.

These are surprisingly involved calculations which although people think of as reasonably commonplace, have traps for the unwary in them. So I recommend having a thorough read of this new interpretation statement. It’s about 40 pages, and it can be found in the latest Tax Information Bulletin.

The proposed Social Insurance scheme may reduce fraud?

And finally, last week I was talking about the Government’s proposed social insurance. This proposes some form of unemployment insurance will be provided, as well as for sickness and other illnesses for employees and contractors alike. As expected, it’s generated a fair amount of interest together with some pushback about costs.

This week an article from Dr Eric Crampton, the chief economist with the New Zealand Initiative caught my eye. He suggested that the new scheme would generate a whole host of rorts. He based his commentary partly on his experience of what went on when a similar scheme was operating in Canada about 30 years ago. Firstly, he suggested employers would put seasonal contractors onto permanent contracts before making them redundant before the end of the picking season. And that would be a win for the employee because they would now qualify for up to six months support. Alternatively, an employer could sack a person who about to take paternity leave. By sacking them they’d get more than the current paternity parental leave payments of $621.76 per week.

Two things stand out. There isn’t much in this for the employer because it is basically fraud. I’m not sure many employers would want to be actively engaged in that. And for that matter, neither would employees. Some of the anecdotes that Dr. Crampton suggested sounded a little bit like, “Well, my friend on Facebook’s third cousin said this.”

But he does make a key point. Fraud is a potential issue for the scheme, and I see two areas where it could be a problem. Firstly, the obvious one – trying to make claims when a person is not eligible. The second area is where a person has a valid entitlement, but the amounts claimed are fraudulent because the numbers have been manipulated to over-state the person’s income.

Under the proposal, the Accident Compensation Corporation is to be responsible for the running of the scheme. Now it has a record of managing ACC fraud. Although interestingly, its latest annual report didn’t cite any numbers as to how much fraud was detected.

But I think if you are concerned about potential for fraud, then you should draw a lot of comfort from Inland Revenue’s enhanced capabilities following the completion of its Business Transformation programme, because the new START system gives Inland Revenue far more capability to analyse data.

And another thing here, which would be different from the stories of how similar schemes may have operated in the past in other jurisdictions, is that we have now Payday filing. This means there is near real time data of salary payments flowing through to Inland Revenue. So again, attempts to manipulate numbers should be picked up very quickly.

That still leaves the self-employed, where one report suggests under-reporting of income might be as much as 20% of income. But one thing that’s going on in relation to the self-employed and especially labour-only contractors, is payments to such persons are increasingly subject to pay as you earn and go through the Payday filing system. So again, Inland Revenue is monitoring payments which gives me some comfort in the matter.

But perhaps counter-intuitively, the introduction of social insurance may mean that we see a reduction in tax evasion. And that is with the opportunity that the social insurance payments represent, people will always want to make sure that they can maximise their benefits. It may well be that persons who previously underreported their income realise that although that might reduce a tax bill it’s no good if you fall sick or your contract is terminated. So, maximising their income is in their best interests.

In answer to Dr Crampton’s concerns about fraud, yes, it could happen. But I think the reality is Inland Revenue are far more sophisticated and have the tools to manage this issue than he gives them credit for. And secondly – as an economist, I’m sure he will appreciate this – perversely, there may be an incentive for people to start reporting their correct income to ensure that they maximise the benefit in case they need to make a claim.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai te wiki, have a great week.