- Comparing New Zealand’s taxation of property with other countries

- OECD heralds a clampdown on crypto assets

- Another warning from Inland Revenue about attempts to manipulate income to avoid the 39% tax rate

Transcript

In last week’s Sunday Star Times, Miriam Bell looked at the question of how New Zealand’s taxation of property compares with other jurisdictions.

In doing so, she spoke to myself, Robyn Walker of Deloitte, and John Cuthbertson, the tax director for Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand. We all gave differing takes on the position.

According to the OECD statistics, we are near the bottom end of the range as a percentage of GDP. Including local government rates, New Zealand’s taxes on property for 2020 was approximately 1.9% of GDP and the total tax take for the year of 32.18% of GDP. By comparison, Australia’s taxes on property was 2.718% of GDP (2019 numbers), the UK was 3.855% and Canada 4.15% of GDP (both 2020 numbers).

As you can see, Canada and the UK are significantly above New Zealand. One of the reasons for this, as Robyn and John pointed out, is that they have a range of stamp duties that may apply. But also, as we all pointed out, all three jurisdictions, Australia, Canada and the UK, also have capital gains tax and in the case of the UK, inheritance tax may also apply on some properties on transfer.

The article provoked a fairly lively debate, as you would expect. The range of views across the board is that, yes, it looks like we’re under taxed. But the bright-line test is in place which is problematic in that although it looks like a capital gains tax, it doesn’t apply comprehensively, unlike in the other three jurisdictions.

Robyn Walker then made a very good point following through that the design of the bright-line test is basically all or nothing. If you hold property for more than 10 years, you’re outside the test, which means that you’re likely not to be taxed on it. So you get this wide variance in the tax effect of sales or property, which you don’t see to the same extent in other jurisdictions.

Robyn subsequently did a nice little post on LinkedIn, in which she looked at what would be the tax consequences in Australia, Canada, the UK, and New Zealand for the sale of a property which realised a $100,000 gain. Because we treat it as income, we’ll tax the full gain at the relevant marginal rate and for the purpose of the example that was 33%. Canada and Australia will tax only half the gain at the relevant marginal rate, although non-residents in Australia will be taxed on the full gain. And although the UK will tax the full gain the top rate applicable is 28%.

The end result was that if the bright-line test applied, then the tax payable in New Zealand would be highest relative to the other three jurisdictions. But if the bright-line test didn’t apply, then it was the lowest. In fact, it would be nil. And this reinforces Robyn’s point that it is a poorly designed test which can be very unfair in its application. You hold a property for nine years and 363 days, you’re taxed. Hold it for 10 years and one day you’re probably not.

The point I stressed in the article is that we want to look at broadening the range of taxation, and it’s fair if we do so because we start to get round these arbitrary distinctions. As I’ve previously said, my preferred methodology for expanding the taxation of capital is that promoted by Associate Professor Susan St John and myself the fair economic return, not a transactional based capital gains tax.

Anyway, this debate will continue to run and run. Miriam Bell’s article provoked a fierce reaction on Stuff, unsurprisingly, and there’s been an interesting debate around Robyn’s LinkedIn article. I urge you to take a look at that.

I think we really do need to address the issue of taxing property particularly when you consider what the Infrastructure Commission said earlier this week about property owners benefiting to the extent of house prices being 69% higher than they would have been without actions being taken to restrict the supply of housing. Housing and the taxation of property is a touchpoint now and will be in next year’s election. We’re going to see plenty more of this debate

Taxes on crypto assets are coming

Moving on to another controversial asset class – crypto assets. Now the value of crypto assets has just simply exploded in the last 10 years. Because of the explosion of the value, it has forced its way onto the tax agenda and tax authorities all around the world are looking to see how this new asset class fits in with their existing rules. New Zealand is no different from other jurisdictions which are all struggling with this. The recent tax bill that was passed last week, by the way, had provisions relating to the application of GST on crypto-assets.

A couple of weeks back, the OECD released a public consultation document proposing a new tax transparency framework for crypto assets. What it has identified is that crypto assets can be transferred and held without going through the normal financial intermediaries, such as banks, and fund managers. And from a tax perspective, there’s no central administrator having what the OECD calls full visibility on either the transactions carried out or on the location of crypto asset holdings.

It also appears that malware attacks and ransomware attacks, payments are increasingly demanded in crypto-assets, which are largely untraceable. So that’s obviously a matter of concern to not just tax authorities.

The OECD paper also points out that some new paid payment products. Such as digital money products and central bank digital currencies, which also provide electronically storage and payment functions similar to money held in traditional bank accounts.

But at the moment, none of these are covered by the Common Reporting Standard on the Automatic Exchange of Information. A reminder the Common Reporting Standard is an agreement between almost 100 jurisdictions where they agree to swap information on financial accounts held in their country by citizens or tax residents of another jurisdiction. It’s been a huge step forward in tackling adn improving tax transparency and tackling tax evasion.

And what the OECD is proposing is, it wants to develop a new global tax transparency framework, which will involve the same reporting for transactions related to crypto assets as for financial assets covered by the Common Reporting Standard. And it’s calling this the Crypto Asset Reporting Framework, or CARF. The paper proposes that the following types of transactions involving crypto assets will be reportable under the CARF:

- exchanges between crypto assets and fiat currencies;

- exchanges between one or more forms of crypto assets;

- reportable retail payment transactions; and

- transfers of crypto assets.

This would bring about a very significant change in the crypto asset world as a result. It will basically be bringing the whole crypto asset world in line with other reportable transactions under the existing Common Reporting Standard framework. I doubt that will be very popular with investors in the crypto world, but it certainly will be for tax authorities and other authorities, such as financial regulators and police, as they deal with the implications of the arrival of this asset class. Consultation is now open on the document through until 29th April.

Same old problem returns

And finally, this week, a couple of weeks ago I discussed the new Inland Revenue consultation paper on countering attempted top tax rate avoidance. It so happens that yesterday RNZ had a story on the paper and Inland Revenue’s concerns that “structures may be being used to reduce incomes below $180,000.”

Inland Revenue has provisionally estimated that income from these high earners will be down $2.88 billion, or about 14% from the year prior. This is on the basis that the average self-employed person – who has the most control over their income – might declare 13% less income than they did the year before, to drop from $191,000 to $166,000 (and by happy coincidence below the $180,000 threshold). The number of PAYE earners is expected to reduce, and also declare lower incomes, from an average of $228,000 to $217,000.

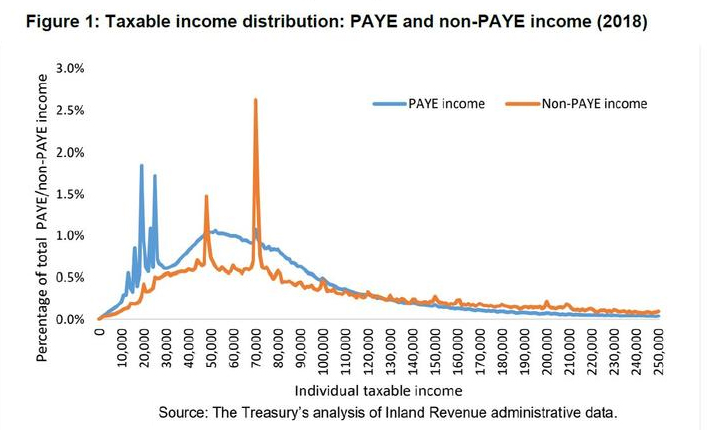

If that is happening then I would expect Inland Revenue to react aggressively. On the other hand, Inland Revenue has known for some time that self-employed income spikes around the $48,000 mark (the threshold when the tax rate increases from 17.5% to 30% and $70,000 dollars when the threshold tax rate increases to 33%). I’m not yet aware of increased Inland Revenue investigation activity into such apparent income manipulation. It seems to me that although Inland Revenue has concerns about manipulation involving the new 39% tax rate, what appears to be happening around the $48,000 and $70,000 thresholds seems very blatant.

The RNZ report included a chart from Inland Revenue of the taxable income distribution for the 2018 income year which illustrated these spikes occurring at the $48,000 and $70,000 thresholds.

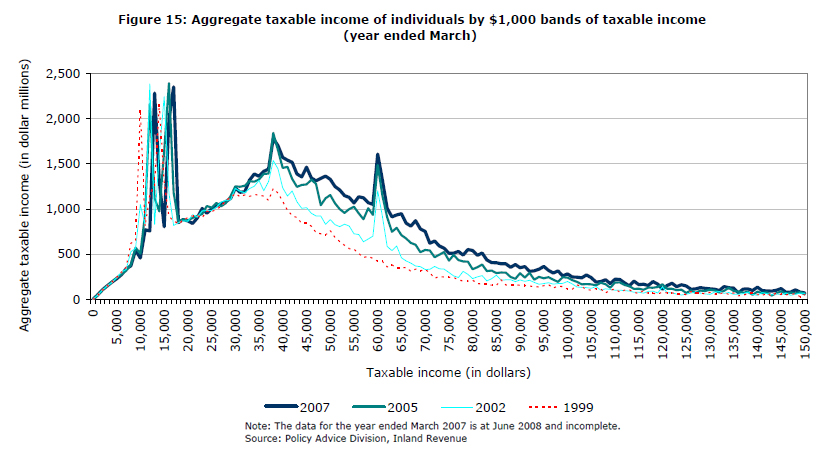

The graph mirrors one produced in 2008 (when the top tax rate was 39%). You can see exactly the same pattern of income spikes around $38,000, the threshold at which the tax rate increased from 19.5% to 33% and then at $60,000 when the tax rate rose from 33% to 39%.

In other words this is a very longstanding problem and the question arises why that issue has been allowed to continue? Does Inland Revenue have the resources to address it? They most certainly will say they do, and they would also probably say that they have had a lot to deal with managing the COVID-19 response over the last two together with finalising the Business Transformation project. Either way you should expect action on this from Inland Revenue.

Incidentally on the question of high tax rates, another news report covered the effect of increases for working for families tax credits. It pointed out that the effective marginal tax rate for recipients of working for families can in some cases be 57%. This is the combination of 30% tax rate on incomes over $48,000 and the 27 cents in the dollar abatement, which applies above a threshold of $42,700.

So before people start complaining about 39% being a very high tax rate, think about what’s going on with working for families, accommodation supplement and other social welfare payments. It’s quite conceivable that someone on $60,000 per annum, receiving working for families with a student loan could have a marginal tax rate on every dollar earned of 69%. This represents 30% income tax, 27 cents on the dollar abatement on their working for families and 12% student loan repayments.

By the way, the $42,700 threshold when the working for families’ abatement kicks in is now, by my calculations, less than the annual income of someone working 40 hours a week on the current minimum wage would earn. It’s another case of where governments have allowed inflation to quietly increase the tax take with worse consequences for people at the lower end of the scale. Yet another issue we’ve talked about repeatedly.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time, kia kaha, stay strong.