- Inland Revenue draft interpretation statement on tax loss carry-forward and continuity of business activities

- Inland Revenue applies little-known provisions to find director personally liable for company’s tax debts

- What role for windfall taxes?

Transcript

Inland Revenue have released an extremely important draft interpretation statement covering the loss carry forward continuity of business activities provisions. These relatively new provisions enable a company to carry forward tax losses, even though there has been a breach of what we call shareholder continuity, so long as the company is continuing the same business activity.

The general rule is in order for companies to carry-forward tax losses for future use, at least 49% of the shareholders must remain the same throughout the period between when the losses arose and when they are used. Tax accountants and advisers pay particular attention to these shareholder continuity provisions because they are all or nothing. If there’s been a breach, you lose all the losses, and they may no longer be carried forward.

We therefore watch this very carefully, but they are not terribly popular and are seen as somewhat cumbersome because they are so hard and fast and they are regarded as impediments to enabling corporate reorganisations, allowing companies to access new sources of share capital or adapt their business activities in order to either grow or become more resilient.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit in March 2020, one of the Government’s first responses was to introduce these business continuity provisions which took effect from the start of the 2020-21 income year. That’s generally 1st April 2020. But as one of the many good examples in the paper illustrates, sometimes the rules can actually take earlier effect.

Under the business continuity rules even if there has been a breach of shareholder continuity, a company’s tax losses may continue to be carried forward despite the breach if no major change in the nature of the business activity carried on by the company occurs throughout what is termed the business continuity period. This is subject to an exemption for some permitted major changes. This draft interpretation statement is therefore very useful in giving us guidance as to how these rules are meant to work.

Tax losses can continue to be carried forward for what is termed the ‘business continuity period’. Typically that is the period starting immediately before the shareholding continuity breach and it ends on the earlier of the last day of the income year in which the tax losses have been used, or the last day of the income year in which the fifth anniversary of the shareholding breach occurs. In other words, there’s a five-year cap on the ability to use these provisions. However, that five-year cap doesn’t apply where 50% or more of the losses are eligible for carry forward arose from bad debt deductions.

These new rules will apply where there’s a shareholder continuity breach starting in the 2020-21 income year and tax losses that arose in the 2013-14 income years or later can be carried forward using these provisions.

The key thing is determining what is the nature of business activities and have they continued? When you’re considering this, you look at matters such as its core business processes, for example, farming, manufacturing, construction, distribution, retailing, etc., the type of products or services produced or provided, what significant assets have been utilized, for example premises, plant machinery, livestock, etc. and if there are any other significant supplies or other inputs, such as key staff and the scale of the activity.

But even if there has been a major change in the nature of the business activities carried on, the business continuity test may still be satisfied if that change is one of four permitted changes. Broadly speaking, these changes can be those made to increase the efficiency of the business activity, to improve or keep up to date with advances in technology, are as a result of an increase in the scale of the business activity or a change of type of products to be provided.

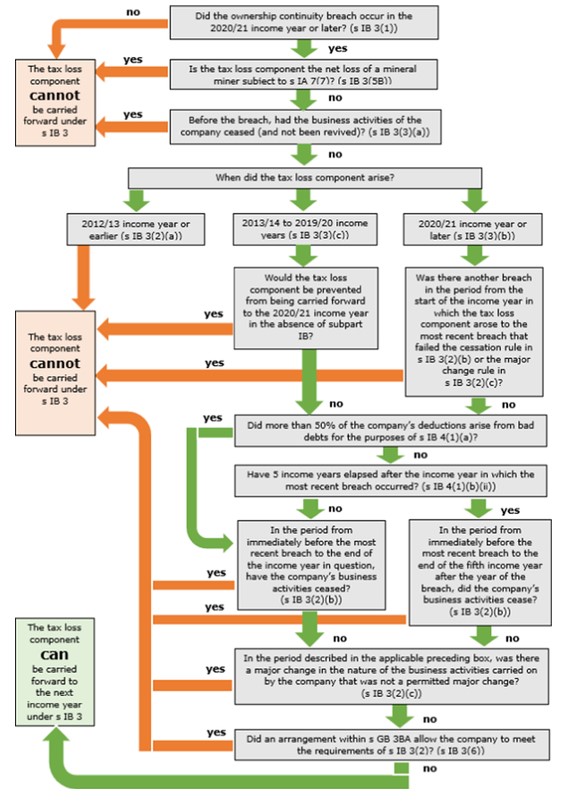

Overall, this is a fairly significant and obviously very detailed interpretation statement. It runs to 54 pages, and includes 15 very helpful examples, together with a useful, if somewhat crowded, flowchart. It’s very welcome to see this guidance as we’ve already handled a number of enquiries regarding the application of these rules. Consultation on the draft is now open until 1st September.

Directors liability for company tax

In previous podcasts I’ve mentioned some Inland Revenue technical decision summaries. Inland Revenue has started releasing these summaries of decisions from its adjudication unit relating to disputes with taxpayers. These are released for information purposes only and are not meant to be formal guidance, such as the interpretation statement we just discussed. They do not represent the Commissioner’s official opinion. That said, they are often very useful indicators of how Inland Revenue might approach certain matters.

We therefore pay attention to what these summaries show and one released this week TDS 22/14 is particularly interesting because it involves a couple of provisions which we’ve not seen used extensively by Inland Revenue.

The facts are a little complicated, and initially the matter at dispute was whether a contractor providing services to a New Zealand company through another company (ABC Co) was an employee of the first New Zealand company. Ultimately, it was determined he was not.

Inland Revenue had a look at what was going on and discovered agreements between ABC Co and another company DEF Co. When these were examined, Inland Revenue concluded that ABC Co was providing services to DEF Co which had been returned. It therefore assessed ABC Co for income tax and GST on these services. These assessments were not disputed by the taxpayer so were deemed to be accepted.

So far there’s nothing particularly unusual about this, it’s what happened next that’s interesting, because when ABC Co didn’t pay its tax, Inland Revenue then deployed two provisions, section HD 15 of the Income Tax Act and section 61 of the GST Act. These provisions enable tax owed by a company to be recovered from the shareholders or directors of the company where there has been an arrangement entered into which has the effect that the company is unable to meet a tax liability.

As I said, these provisions have been around for a while, but I’ve not previously seen them used. In order for them to apply there has to be an arrangement, the effect of which is the company has a tax liability whether an existing one or one which arises later which it cannot meet. It must also be reasonable to conclude that a purpose of this arrangement was that the company could not meet that tax liability. And finally, would a director who made reasonable enquiries at that time have anticipated that a tax liability would or would likely, be required to be met? So, there’s a few hurdles to get through before the provisions apply which is why we probably haven’t seen much use of it previously.

In this particular case, the arrangement appeared to be that the taxpayer’s private expenditure was met at all times, but the company never had any funds available to meet any tax liability. So that’s why Inland Revenue ultimately decided to apply these agency provisions.

Understandably, the taxpayer disputed the matter, but the Adjudication Unit ruled on Inland Revenue favour. As I’ve said, these provisions have been around for a while but have not seen much use of them, which also makes it uncertain when advising clients as to what could happen. Until now we’ve advised these rules could apply, but we haven’t seen much evidence of them being used. Now that has changed. This seems very much like a warning shot from Inland Revenue that feels it can deploy these provisions and obviously is doing so as part of a harder line on debt and attempts to avoid payments of tax debt.

It will be interesting to see whether this case progresses any further, for example if it’s taken to the Taxation Review Authority or High Court on appeal. More importantly, will we see more use of these provisions by Inland Revenue. As always, we’ll keep you up to date on developments.

How likely is a windfall profits tax?

And finally, this week, the rising cost of living has been in the news, as has obviously the Government’s response. As people should be aware part of that response involves a cost-of-living payment of $350, which Inland Revenue is now about to start paying, even though there’s about 160,000 people for whom it doesn’t have any bank details and who may therefore miss out on these payments.

There’s also been plenty of debate about what’s causing the spike of inflation and what can be done about that. And an issue that popped up this week was the question of windfall taxes which have re-emerged as tools in perhaps in fighting inflation. Italy, for example, introduced one last year on extra profits realised by Italian energy industry companies. The Spanish have a similar one, also targeting energy production companies. And in May the UK government announced a 25% energy profits levy charged on profits from UK oil and gas extraction activities.

I was asked by Geraden Cann of Stuff whether such a tool could be used here, and my response was not immediately, because we have no history of such taxes, although I understand that there were excess profit taxes levied in both world wars with varying degrees of success. I think most countries struggled with how they could define excess profits in that case.

But then following through on this issue, I did suggest that there might be room for developing such a windfall tax on the principle that it’s always good to speak softly and carry a big stick. However, that would involve determining what would be the trigger points as to when the tax would apply. When would they apply? What constitutes excess profits subject to the tax? What rate would apply? And for how long would such a windfall tax supply? There’s a lot to consider and they would be very complex to design.

Furthermore, although the Government might think, “Well, gee, that’s a nice stick we’d like to have”, businesses quite rightly would be saying “We’re not happy about that because who could be the subject of a windfall tax”.

Currently, windfall taxes are being applied to energy companies in Europe. However, in the past Britain has applied them to banks and privatised utility companies. Businesses might therefore be a little cautious about how they might invest if they felt there was a reasonable prospect of a windfall tax applying. Now our tax policy settings are very much about providing certainty for businesses and business investment. So, on that basis, I can’t see a windfall tax appearing any time soon, even though quietly a finance minister might like to have such a weapon in his or her toolbox.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!