- Land taxation

- Is the disputes process fair?

- How much tax could legalising cannabis yield?

Transcript

Inland Revenue has just released an Interpretation Statement IS22/03 income tax – application of land sale rules to co-ownership changes and changes of trustees. Now, this is actually quite an important Interpretation Statement because it looks at whether the land sale rules in the Income Tax Act will apply when there is a change of co-ownership in an interest in land or a change of trustee.

It’s important because the Income Tax Act has provisions where a tax charge arises, where there is a disposal of land. And the question that’s been raised is whether any changes in ownership or changes in trustees represent a ‘disposal’ for the purposes of these rules, because obviously, if they do, then that could have significant implications under the bright-line test, for example.

The Interpretation Statement concludes when you consider the ordinary meaning and applied case law in context a disposal for the purpose of the land sale rules means or requires a complete alienation of the land by the disposal. In other words, that person must get rid of the land.

And helpfully the Interpretation Statement includes a number of transactions as examples. Where there’s a change in the form co-ownership, where the proportional shares or notional shares do not change, that is not a disposal for the purposes of this land sale rules. On the other hand, if there is a transfer between co-owners where neither’s interest is fully alienated, but the proportional share or notional share of a co-owner is reduced. there would be a disposal for the purpose of the land sale rules by that person to the extent that interest is reduced.

Inland Revenue’s argument in support of this is that because, although they’ve not fully alienated the whole interest in that land, they have fully alienated a part interest in that land. And similarly, if there’s a transfer that adds a new owner, there must be a disposal involved for the purposes of the land sale rules to the extent that the share or notional share of an original owner or co-owners in that land have been reduced. Similarly, a transfer that removes the co-owner would also be disposal by that departing co-owner of their interest in land.

Now on the matter of a change in trustees of a trust that will not be a disposal for the purpose of the land sales. And that’s because the Income Tax Act treats all trustees of a trust as essentially a single person. And therefore, in this case, disposal does not include a transfer to yourself, i.e. in the same capacity. Trustee swaps out, new trustee comes in, the title has to be reregistered and that’s not a disposal. On this basis, I think most people generally thought that was the case. But it’s good to see Inland Revenue come out and make that position clear.

There’s a useful table in the Interpretation Statement setting out examples of the Inland Revenue conclusions on this. There’s also a handy fact sheet available.

Heads the IRD wins, tails you lose (because you will never be able to afford to challenge their decisions)

Moving on, last week I referred to an Inland Revenue Technical Decision Summary. Now these technical decision summaries are issued by Inland Revenue’s Tax Counsel Office following an adjudication in a dispute or as part of the private rulings process. As I mentioned, they’re interesting to see because although they’re not binding on the Commissioner of Inland Revenue, they do give an indication of the types of cases Inland Revenue is encountering, and their likely thinking on an issue.

How taxpayers and Inland Revenue resolve matters where they cannot agree is an important part of any tax system. Inland Revenue has just released an exposure draft of a revised standard practice statement on the operation of the disputes process. When finalised, this practice statement is intended to replace two previous practice statements, one which dealt with where a dispute resolution process has been commenced by Inland Revenue, and the other where the dispute resolution process is started by the taxpayer.

Inland Revenue has decided to merge the two into a single statement and include some updates to the process, taking into account some relatively minor legislative changes that have happened recently. These relate to the introduction of what’s termed “reportable income” and “qualifying taxpayers” as part of the auto calculation of assessments process. The dispute process has been tweaked to deal with the introduction of these terms concept.

This is fairly routine maintenance by Inland Revenue. However, I think it ought to have taken the opportunity to look at the dispute process much more closely and whether it works for well as everyone involved with it as it should.

It so happens this is something I looked at for the Tax Working Group back in 2018. And in researching the matter I came to the conclusion that there are quite a few issues with the present dispute regime. In particular it’s expensive, very time consuming, and its costs act as a barrier to all taxpayers, but particularly smaller taxpayers.

Inland Revenue’s Adjudication Unit is part of the disputes process. It gets involved after there has been the initial stages of a Notice of Proposed Adjustment, or NOPA, and then the Notice of Response (NOR). After those formal positions have been issued by the parties to the dispute they then try and resolve the matter through negotiation. And if they can’t, it can be referred to the Adjudication Unit and.

Geoffrey Clews QC was involved in making some minor changes to the dispute process, to improve it about ten years ago. He commented on his experience working with Inland Revenue officials “reinforced the impression that [Inland Revenue] is very conscious that it presides over a tax administration which is weighted in its favour. It is reluctant to see that change.”

This is perhaps not surprising, but it should also be a bit of an alarm bell.

And then separately, two Supreme Court justices, Justices Glazebrook and Young, raised concerns about whether the dispute process was deterring taxpayers. They both noted there’d been a significant decline of tax cases coming through the court system. It’s now down to maybe 10 or 12 a year.

Justice Glazebrook, who is a former tax lawyer commented further on the disputes process in a speech to the Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand Tax Conference in 2015.

“What is not so positive is the concern that the dispute resolution processes, even in simple cases, takes a lot of time, effort and therefore cost to complete. When this is coupled with the new penalty and interest regime, with its differential interest rates for taxpayers and the revenue, the concern is that taxpayers are ‘burnt off’ by the taxation disputes process. This means that taxpayers may be forced to settle legitimate tax disputes as they cannot afford the time or money necessary to continue court proceedings.”

Now, this draft statement of practice doesn’t address these issues. It’s not designed to because it’s intended to be just a largely restatement of the existing system. However, I think Inland Revenue should not be afraid to have a further look at think about how the dispute process currently works. It’s been ten years or more since we last looked at it. As I said things that’s notable is there isn’t a lot of activity going through the courts. Although everyone’s right now waiting to hear what the Supreme Court’s going to be saying about tax avoidance in the Frucor court judgement.

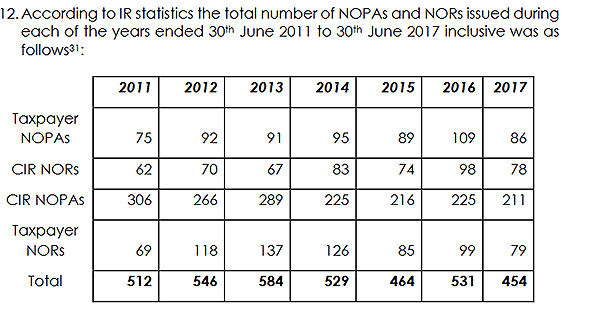

According to data supplied to me by Inland Revenue back in 2018, the average number per year of NOPAs and NORs i.e. matters in dispute over a seven-year period was 517. Now, in the context of nearly 5 million active taxpayers on a pretty controversial topic where people’s opinions and interpretations differ quite markedly, 517 disputes a year seems incredibly low.

The counterargument would be the process is working properly and the issues are being resolved much earlier. To be fair, that’s certainly true to an extent. But a cynic might also say Inland Revenue is not picking up enough of this stuff either. That may come down to a question of resourcing. Inland Revenue believes it’s fully resourced, properly resourced but looking from the outside I’m not quite so sure.

Although it’s always good to see Inland Revenue clarifying matters and updating its statements of practice, I think there is a major point still to be addressed about whether the disputes process is working as it should and if it’s not, what can we do to improve it?

Tax, cannabis, and gangs

And finally, this week, a quirky story coming out of Christchurch caught my eye. Brendan Crocker appeared in a district court this week charged with cultivating cannabis and for possessing a Class C drug for the purpose of selling In the course of his hearing it emerged that he admitted to starting a company so he could pay tax on his sales. That’s one of the more unusual excuses involving tax I’ve seen, too. Crocker claims he gave away about 80% of his cannabis candy in order to help people in pain and was only selling the rest to cover the cost of making it.

Gangs are currently in the news and there’s plenty of concern about the increase in gang violence in and around Auckland. Now it’s well known that one of the things that fuels gangs and gang tension is the trade in illegal drugs. This is where tax comes into play. Why not legalise or decriminalise cannabis? By doing so, we’d take control of the supply away from gangs, and hopefully therefore reducing their influence. Many countries have done this with Thailand one of the latest, and quite a few states in the United States have done it as well.

Once the sale of cannabis is decriminalised, it can become a useful source of tax revenue. And of course, that tax revenue can be used to deal with the problem of gangs and drugs. As I see it, it’s a win-win.

Colorado in the US. has a population of about 5.8 million, roughly comparable to ourselves. It legalised cannabis way back in 2014 and it publishes monthly records of its marijuana tax take. Currently it’s around US$19 million per month, which is roughly NZ$30 million, give or take, which equates to around about $350 to $360 million a year.

To put that in context, that tax revenue is probably more than what is going to come from the Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 international tax reforms that I discussed last week. Now they are a big deal for international tax, but the actual cash benefit for New Zealand is probably not as significant as many people might think.

On the other hand, cannabis, illegal drugs, gangs and the accompanying violence and threats is a problem as well as great cost to us. So that’s a proposal for someone serious to consider. Legalise cannabis, get some useful tax revenue. And then use that to help deal with the problem of drugs and gangs.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. ’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!