- Shareholder advances under Inland Revenue scrutiny – are you paying FBT on these advances?

- More about using cheques to pay tax

- Australian tax complications when purchasing property

Transcript

This week, Inland Revenue gets curious about loans to shareholders. More about how you can pay your tax and the cost of investing in Australian property just went up.

Listeners will recall one of my previous guests was Andrea Black, who at the time was the independent advisor to the Tax Working Group. Andrea has moved on and is now the policy director and economist at the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions taking over from Bill Rosenberg, a fellow Tax Working Group member.

Andrea has just published a Top Five piece on tax and paid employment.

And one of the top five items caught my eye, because it picks up some other things that I’ve been seeing, has to do with advances from companies to shareholders.

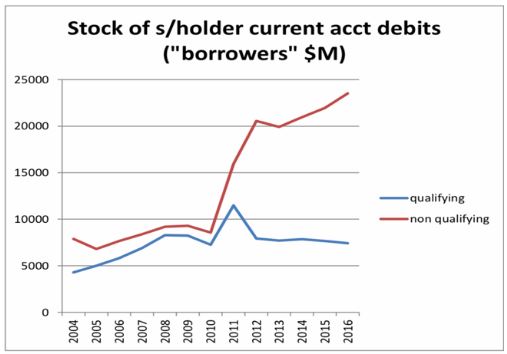

Now, the interesting thing that’s emerged from the Tax Working Group is what happened after 2010 when the tax company rate was cut from 30% to 28% and at the same time the top personal tax rate went down from 38% to 33%. Since then amount of loans advances from companies to shareholders has exploded, and there is an eye-catching graph in a Tax Working Group paper which shows the value of shareholder current account advances.

And they’ve gone from just under $10 billion in back in 2010 to nearly $26 billion by 2016. So, what’s happening here? Well, it appears that this could be a way of people trying to avoid paying the top 33% tax rate because company profits are tax paid at 28% and then the taxpayer then receives an imputed dividend and then tops up the 5% differential, assuming they’re taxed at the top rate.

But what happens if instead the money is advanced as an interest free loan or a loan to a shareholder? Now, there are rules around this, and interest free loans are subject to a prescribed interest rate. This has been cut to 5.26% with effect from 1st of October 2019. If you’re not charging interest, you are required to charge this prescribed interest rate of 5.26% on any overdrawn shareholder current account.

Now that is a longstanding rule, but in my experience, it’s not always observed, and I even had an interesting case at the start of an Inland Revenue review. The company did have an overdrawn current account for some shareholders. We advised Inland Revenue as you are supposed to saying “Look, oops our bad. This is an overdrawn current account and we haven’t been charging interest. Here’s the amount of interest we should have been charged”.

What was interesting about this case was it involved a fairly sizable company which had independent advisors, who ought to have known this. More curiously, the Inland Revenue investigator didn’t seem to be aware that that this could have been a problem. Perhaps this is why these current account debits have been gradually growing without too much observation from Inland Revenue.

So, the issue which arises here is have those companies being charging interest and if so, have they charged interest at the correct rate? Otherwise, there’s probably a load of FBT going to be payable. And why exactly are they doing this? If there is a constant pattern of substitution of, say, a salary or dividends with drawings made through the current account, Inland Revenue could follow the lead it took in the Penny-Hooper case. You may remember that case from nearly ten years ago. Inland Revenue may say, “Well, this actually constitutes tax avoidance and we’re going to treat these drawings as additional salary or remuneration”.

So, it remains to be seen what’s going to happen in this case. This is another head’s up. If you’re a company and you’re advancing money to your shareholders and you’re not charging the prescribed interest rate of 5.26% then you potentially have a problem on your hands.

And what I think we can also say with some confidence is that matters highlighted by the Tax Working Group as requiring work will be picked up by Inland Revenue as part of their work programme. The data mining capabilities of the Inland Revenue are now greatly enhanced, so I would anticipate seeing a lot more “Please explain” letters coming from Inland Revenue investigators.

Following on from last week’s item about the fact that Inland Revenue is withdrawing the general application ability to pay tax by cheques from 1st of March, earlier this week I went to a meeting between tax agents and Inland Revenue staff. And this point got raised with several agents saying, “Well, we’ve got elderly clients who either have no access to online banking or don’t know how to use it. They’re not happy about it. And we’re not happy about this”. Two things emerged from this discussion. Firstly, the Inland Revenue staff acknowledged this was something that was a potential problem. But they also pointed out that in fact, in certain circumstances, Inland Revenue will allow cheques to continue to be used to meet tax payments. Coincidentally, also this week, a new Statement of Practice SPS 20/01 was released by Inland Revenue which explains when it considers tax payments to be made on time.

The SPS discusses what the alternatives for people who used to pay by cheque, and can and are concerned they may no longer do so. And it gives a couple of examples about the options. One involves John who lives in a remote rural area and lives off the grid. He does not have any access to the internet nor a reliable phone service and is hours away from any banks. So, in this case, Inland Revenue would agree that his circumstances are exceptional, and he may continue to pay his tax by cheque after 1st March 2020.

The alternative example is another elderly person, Mary who is aged 75. She doesn’t have access to the Internet either. She has no Westpac branch. (You can actually rock up to a Westpac branch and pay your tax in cash or by using a debit card). Mary does have an EFTPOS card and the Inland Revenue here say:

“Through discussion with the customer about her circumstances, it was agreed that she is able to, with assistance by phone, set up a direct debit with us, or make payments using an automatic payments form. On this basis, an exceptions arrangement to pay tax by cheque post 1 March 2020 would be declined.”

So, there are instances that you can still continue to pay by cheque, but it’s very much a case by case basis.

I stand by what I said last week. I think that this is blanket policy which should not be allowed. I would say in that example they give about Mary, elderly people like that would be very, very cautious about talking over the phone to someone about paying tax. Particularly since Inland Revenue is sending out frequent reminder warnings about the phishing and phone scams going on.

So, I think you’ve got this dichotomy between Inland Revenue wanting to minimise its own administrative costs and not actually addressing the real concerns of people who are concerned about using online and phone banking.

The second point came out of the discussion was also pretty interesting, was that Inland Revenue had also said that in future, when either setting up or updating your bank account details, it would require a direct debit.

Now, that caused quite a stir amongst the tax agents. And let’s just say there was a full and frank exchange of views on the matter, which also coincided with us being advised that, in fact, that particular advice was going to be withdrawn. Clearly, quite a lot of people have said, “Wait a minute, what’s this?” because cancelling the direct debit with Inland Revenue is not that easy. The takeaway here is you do not have to set up a direct debit with Inland Revenue unless you really want to. Therefore, proceed with caution.

And finally, and this is a long running issue for me, a warning how the tax consequences of investing in Australia are often overlooked. There is a lack of awareness that, first of all, Australian capital gains tax will apply to property. But secondly, there’s also all the other hidden charges involved in investing in Australian property, such as Stamp Duty – or as they call it in New South Wales – Transfer Duty.

What caught my eye this week is that the state of Victoria, has announced it will withdraw its grace period for exempting foreign purchaser additional stamp duty on residential property.

This would apply to discretionary trusts that have foreign beneficiaries, for example, a New Zealand trust with, say, three beneficiaries here and one in Australia. This will now become regarded as a foreign trust for surcharge tax purposes unless the trust deed is amended to expressly exclude the foreign persons, that is the New Zealand residents as potential beneficiaries of the trust.

The change may mean that there will be a surcharge payable on the purchase by a New Zealand trust of residential property in Victoria. New South Wales has similar rules. In fact, there is a Surcharge Purchasers Duty of 8% for residential land purchases by foreign persons, which would include a foreign trust. New South Wales also has a land tax and it imposes a 2% surcharge for residential land purchases by foreign persons.

So, this is very much a case of if you’re investing in Australia, be aware there are great tax complications. I always tell my clients, “Don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog”, but you really have to be sure if you are investing in Australian property that the returns justify the additional tax consequences that you’re going to incur.

And on that bombshell, that’s it for The Week in Tax. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time have a great week. Ka kite āno.