Tax Policy Charitable Trust Scholarship co-winner Andrew Paynter on his proposal to increase GST to 17.5% with a refund tax credit for low-and middle-income individuals.

My guest this week is Andrew Paynter, a policy advisor at Inland Revenue and co-winner with Matthew Seddon of this year’s Tax Policy Charitable Trust Scholarship. The Tax Policy Charitable Trust was established by founder Ian Kuperus to encourage future tax policy leaders and support leading tax policy thinking in Aotearoa.

Andrew Paynter’s proposal is to increase the rate of GST to 17.5% and introduce a GST refund tax credit for low-and middle-income individuals.

I should make it clear here that everything in Andrew Paynter’s proposal and what is in this podcast represents his views and not those of Inland Revenue. Kia ora Andrew Paynter, congratulations on your win and welcome to the podcast. Thank you for joining us.

Andrew Paynter

Thank you. That’s very kind. And yes, it’s great to be here and I’m really excited to have a chat with you.

TB

Me too, it is a very interesting proposal. And so how do you land on choosing this? There is a pretty free rein in choosing topics for the scholarship. But what drew you to this particular proposal? .

The background

Andrew Paynter

Yes, sure. For me, something I’ve been interested in ever since I’ve worked in the tax space is the New Zealand Crown’s long term fiscal position. And we know from the New Zealand Treasury’s most recent long-term insights briefing He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021 that as we look into the future, the Crown is going to be spending at quite a higher rate than it is getting revenue.

And for me, I think that puts New Zealand in quite a weak position to manage its daily societal needs. But also to manage future disasters, pandemics and economic shocks. And we know that these things are going to happen more often and probably at a greater severity than they have in the past. So that was sort of my starting point. I guess that was the thing I was interested in, and I wanted to try and develop some form of solution to that.

TB

Yes, I mean, this is something long-time listeners to the podcast keep hearing me banging on about Treasury’s statement on the long term fiscal position. I also note in its briefing to the new Finance Minister, Treasury says there is a structural deficit of 2.4% of GDP. So we have a fiscal gap already, according to Treasury. I mean people talk about reducing expenditure, but that will only take you so far, particularly when expenditure is going up faster than you can reduce it, to be blunt. So why did you land on GST?

Why increase GST?

Andrew Paynter

I think there’s quite a few reasons that I landed on GST. I guess the two main points are about finding a revenue raiser that embodies good taxation principles.

And then the second part is trying to find a revenue raiser that I think has better impacts than other revenue raisers, particularly in relation to effectiveness and efficiency.

So, on that first point, embodying good taxation principles. It’s really important that any revenue raisers that we choose are aligned with broad-based low rate, and that’s ensuring that we maintain f broad-based low rate at an entire tax system level, and at a regime level.

Of course, when we look across the New Zealand tax system, I think we can all agree that one regime in particular stands out as being super broad-based and that’s GST. We know GST has few exemptions and exclusions, but it also has the highest value added tax revenue ratio score in the OECD by quite some margin.

TB

Yes, that’s quite a stat. In fact I think only Chile raises a higher proportion of tax from GST than ourselves?

Andrew Paynter

I’m not entirely sure if that’s correct, but I do know for the revenue ratio score, I think Luxembourg has the second highest score in the OECD. But we outscore Luxembourg by quite some mark. And I think we have double the OECD average in New Zealand. So, it’s quite a difference.

GST – the broad base, low rate exemplar

TB

That’s taxing everything. It’s as you say, it’s the exemplar in the system of the broad-based low rate. Even if you’re you’re proposing to raise it to 17.5%, even then, that would still be below the OECD average, isn’t that right?

Andrew Paynter

Yes. The OECD average rate is 19.2%, so 17.5% is still nearly 2% below the average.

TB

How much would that raise? This is the thing the politicians say. OK, how much would we get if we increased it by 2.5 percentage points. What’s the potential take?

Andrew Paynter

Yes, I think obviously it depends on a huge raft of dynamic factors like inflation and consumption patterns. If the rate was applied in the 2023 tax year it would have raised an additional $4 billion in revenue. So that gives like a proxy for what’s possible.

TB

Wow. I mean, that’s one percentage point of GDP. So that is a significant amount. But the question is, as I said, why GST? There’s a lot of debate around capital taxation as well, wealth taxes, capital gains tax and occasionally, not so much though, estate duty/death duties/inheritance tax. In your paper, you talk about GST being a one-off taxation on the wealthy. Can you elaborate on this?

How GST represents a one-off tax on the wealthy

Andrew Paynter

Two interesting parts to that really. I was again looking to this future fiscal deficit and trying to think of revenue raisers that suited that future context. And one thing that we know is underpinning part of the deficit (obviously it’s not the whole thing, but part of it) is having this ageing population. And so, is there a way to leverage revenue from an ageing population? Of course, as the population gets older, a higher percentage of the population is earning less taxable income, but they are consuming often more than the means of their income as they’re drawing down on savings. So, increasing the rate of GST becomes in a way an effective one-off taxation on all the current and future wealth that exists in New Zealand so long as that wealth is then consumed in New Zealand on taxable supplies.

TB

So if the ageing population skips off to spend its money overseas that is outside the GST net. But the likelihood is, as you say, they’ll consume more and more of it in New Zealand effectively because their income has declined.

Andrew Paynter

Yes.

TB

This means the GST relative to what their income as a proportion of the total tax they might pay, will rise on under this measure. Yes, so interesting analysis there but we don’t have a lot of evidence.

Andrew Paynter

That’s correct, yes.

TB

Maybe we don’t have as much statistical evidence as we would like. The empirical evidence to talk about, the behavioural impacts of this. But GST’s not really subject to the same behavioural impacts as other taxes, because you can either spend it in New Zealand or spend it offshore. And as we said, your opportunity to do that has become limited because physically you may not be able to travel, or it becomes too expensive to travel.

Andrew Paynter

Yes, that’s right. Some interesting analysis is that when you do increase GST or just a VAT or consumption tax in general you do get potential behavioural responses. You know, substitution effects, price elasticity responses, etc. But some of the academic analysis I found was that when you introduce a rate increase alongside a compensation measure, those behavioural responses are often quite muted. So you don’t actually get the same response that you would if you just did a GST rate increase by itself. And obviously, this proposal does have a compensation measure aspect to it.

What about inflation?

TB

Yes, we’ll come to that in a minute. One of the other things that may come into play around a GST increase, is it’s potentially inflationary. How do you deal with that effect, how have you calculated that potential effect and how long would it last?

Andrew Paynter

It’s quite interesting. I think we have some precedent in New Zealand that we can look to. For the 2010 GST rate increase, the government of the day had modelled that the inflationary response would be about 2% immediately after the introduction of the new rate. That was reflecting an immediate 2.5% price increase on all taxable suppliers, and then some form of future and lagged response on non-taxable supplies like rents, but those are a lot harder to quantify.

So, you certainly do get a significant inflationary impact, but I think that because the Reserve Bank has the discretion to look through temporary inflation shocks in the way that it sets its monetary policy, in theory it shouldn’t have very significant economic consequences. And again, I think, we can look back to 2010 and see that.

TB

Yes, we want to avoid that horrible double whammy – prices have gone up and then interest rates go up, that is a real nasty spiral.

Andrew Paynter

Yes, that’s right.

TB

And as we mentioned before, GST is as incredibly efficient tax. Businesses were collecting it and everything fell into place very smoothly. I’ve been around long enough to remember that after the 2010 increase things fell into place pretty smoothly.

But the big downside though for GST, (and the last Tax Working Group touched on this) and the taking GST off food was a partial response, is that GST is actually a regressive tax. Particularly for the lower- and middle-income earners. And the second part of your proposal deals with that. What are you proposing there?

Ensuring equity through a targeted GST refund tax credit

Andrew Paynter

As we noted before, the inflationary impacts of a GST rate increase means that businesses are passing on the full cost of the GST rate increase to final consumers.

And so that means prices are going to immediately increase relative to incomes. That’s obviously a problem. We have relatively high levels of inequality in New Zealand, so low to middle income New Zealanders don’t necessarily have the means needed to absorb that price impact.

Then on top of that, as you mentioned, GST is regressive. I know it’s argued that it’s not necessarily regressive over an entire lifetime, but I think the fact that it’s regressive, at least at a point in someone’s life, it can impact on their economic position, which can then have lifelong implications on them economically. To address that I’m proposing that a targeted GST refund tax credit should be introduced to offset that impact.

TB

How would that work?

Andrew Paynter

It’s a very good question. We were touching on it in a conversation we were having off-air earlier, with all social policy initiatives when you’re choosing a compensation measure or when you’re just designing that compensation measure, it’s all about trade-offs and deciding on what values and objectives you value more than others and what you’re trying to achieve.

We can discuss the design parameters for the credit in a second, and I’m sure we will. But I guess I just wanted to highlight that this is just one way to do it. It’s not necessarily the only way and it’s not necessarily the only “right” way to do it. It really depends on what you’re trying to achieve.

TB

Because there’s quite a bit of interest around this sort of mechanism around the world, isn’t it? The IMF released a working paper in April just as you were writing your initial proposal. But that was completely different. And that was a refund that comes through as point-of-sale credit. You mentioned in your paper that Canada has been doing it.

Andrew Paynter

Yes, that’s right.

TB

So, similar to what you’re doing?

Andrew Paynter

Yes. As you said, the IMF compensation measure is completely different to a tax credit like I’ve proposed. Whereas Canada’s example is a tax credit, as they call it, the GST/HST refund tax credit but the design parameters reflect the realities of the governmental and tax systems in Canada so it’s quite complicated.

Although we could look to these examples for some inspiration, I think that the parameters that we select for the New Zealand context should be rooted in the realities of our government structures, and also our transfer system and our tax system.

Resolving the problem with abatements and marginal tax rates

TB

You note in the paper that transfer payments have been sliding lower relative to median incomes over time. Then what you’re driving at is that one alternative might be “let’s increase the alternative transfer payment”. But they all come with heaps of abatements as you point out.

I was reviewing Inland Revenue’s annual report before today’s podcast and a stat that jumped out at me on this point was that only 22% of people receiving Working For Families credits do not have an abatement. That threshold is $42,700, which means 78% are being abated, and that’s at 27.5%.

So, you want to avoid that because it just increases this whole problem of effective marginal rates. How do you intend to do that? You’re taking what they call a fiscal cliff approach. Is that right?

Andrew Paynter

Yes. Part of the design of the credit that I’m proposing is to use a cliff face approach. As you touched on, abatement is where your entitlement, whatever that may be, is decreased by a specified percentage for each dollar you earn over whatever the threshold is.

So, when you compare that to a cliff-face approach (which is where your entitlement just ends once you hit the threshold) you don’t get the same impact on effective marginal tax rates.

You still get work incentive impacts, but those are a lot sharper and shorter. So given as you say, there’s lots of interacting abatement payments in the New Zealand context, for those reasons I’m proposing that the credit utilise the cliff face approach.

TB

Yes, you’ve also said it’s to be individual, so it’s not calculated like Working for Families on a collective family unit. It’s on an individual basis because the evidence shows you wouldn’t be getting much potential abuse of the credit. Why an individual credit rather than a family credit?

Andrew Paynter

It’s various factors. I think one point is again touching on that Canadian example. In Canada, I believe you can file as a family or as a couple. Whereas in New Zealand, all of our filing is individualised. The administrative realities are that unless you’re in a regime like Working for Families, you don’t necessarily have those connections within the tax system to your partner.

Individualising the credit therefore aligns with the individualised nature of New Zealand’s tax system. It means that you don’t need information from your partner in order to get the credit. Which means that you can automate it because you don’t have to have an application process that says, this person’s my partner and this is their income. On top of that I was looking at the Household Economic Survey and it really looks like consumption patterns don’t vary greatly between one person household consumption data versus two person households. Consumption is quite an individualised thing.

TB

That’s encouraging, because the simpler this is, the better in my view.

Andrew Paynter

100% agree.

What’s the threshold?

TB

And so, the threshold you were talking about would be about $69,000.

Andrew Paynter

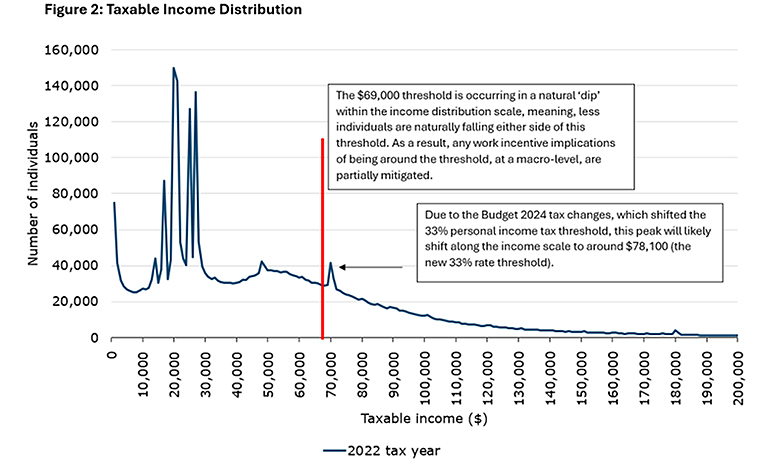

Yes, I’m proposing that the threshold for the payment is $69,000, which is the median income from salary and wages. Obviously, it can be quite hard to define what we mean by low to middle income. But I think choosing this middle point makes sense for this notion of low to middle income.

You have less people naturally falling in that $69,000 space comparative to other parts of the income scale. And that means that those work incentive impacts that we talked about, are affecting less people, which I think is quite important from a macroeconomic perspective when compared to other parts of the income scale where you could put the threshold.

TB

Yes, we see distortions around thresholds all the time. It’s quite blatant actually. You can see spikes in your graph at $70,000 and then $48,000. Don’t know what they have to do with it other than threshold increases.

Andrew Paynter

Yes. That’s right.

How frequently?

TB

This credit though, it would be payable quarterly. Is that correct?

Andrew Paynter

Yes, I’ve chosen a quarterly model for paying and that quarterly model is full and final and that was to balance a few factors. It was to ensure that people are actually getting the credit close to the point in which they’re incurring the increase in GST, versus if you did a year, you might incur some form of increased cost towards the start of the year and you’re waiting quite a significant amount of time to get the payment. And again, given that this is targeted at low- or middle-income individuals, that sum of money is quite important.

Also, if you had a shorter time period, such as a week, it might be a bit more administratively difficult. For example, it’s hard to know how much people are actually getting paid as if a weekly model was chosen people’s pay periods might not align with that.

Having a quarterly full and final model also means that there’s a low demand for reassessments and that’s going to be important from an administrative perspective for Inland Revenue. Also, debt situations are avoided because you’re doing a lagged income model and that means people don’t have to guess what their income is going to be.

TB

I think that’s incredibly important because when you see the stats, the debt’s building up. I mentioned earlier about the abatement issues for Working for Families and you say it’s full and final. So, in the quarter a person earns below the threshold, they get that payment and then for the next three quarters, they’re well above that.

But there’s no requirements to say, for example, they’re total income for the year was $80,000. But for the first quarter, they were within that $69,000, but that’s they received a final payment then and that’s it. No going back. No “backsies” from Inland Revenue to go back and re-assess.

Andrew Paynter

Yes, that’s right.

TB

And because as you say, the cliff face approach takes care of that because they get cut off, but hopefully their earnings have risen enough to mitigate the impact of the inflationary increase in GST.

Andrew Paynter

Yes, that’s right.

TB

I’m all for keeping it as simple as possible, otherwise the system gets bogged down with a lot of resources chasing relatively small sums of money. I think there are mechanisms to deal with that, and that’s the other part in here.

You’ve set out some different things you’re basically trying to automate as much as possible within Inland Revenue’s existing processes.

Definition of income?

Andrew Paynter

Yes. Again, having the credit individualised as we touched on earlier, means you don’t need partner information. I also propose that the credit is based on a definition of taxable income, not something of a broader like economic income, which agencies like the Ministry for Social Development use for benefit payments. Inland Revenue already holds taxable income information in the course of its usual tax activities.

And then because it’s individualised and you don’t need partner information, it should in theory just be this really automated process where you know, me as an individual earns salary and wages and as long as I’m under the threshold for the quarter, as long as Inland Revenue has my bank account information, I will just get the payment.

TB

I like that approach. Obviously you’ve got great feedback because you’ve won. But what feedback have you received from that? Is there a potential that your proposal might be taken further? Did Nicola Willis come up and say “ “Come and have a word with me I like this.”

Andrew Paynter

Obviously everyone’s been very kind and very supportive, but whatever happens with my proposal, I’ve simply just come up with the idea. I’m obviously proud of my idea and all the work I put into it, and I have simply just put the idea out into the world.

TB

That’s fantastic. Any final thoughts on what’s next?

Andrew Paynter

What’s next? I’m not sure. A bit of relaxing I think. I guess one thing I would just say is if there’s any younger tax professionals listening to the podcasts or want to be tax professionals, it’s a really awesome competition and it’s a great opportunity to tackle some form of issue that you’re passionate about.

You’ve got the time and the space to develop a solution that you really care about and then you get to have it tested by leaders in the tax space. And I think that’s a really cool opportunity. So I heavily encourage anyone who meets the eligibility criteria to apply.

TB

I thought the standard this year was extremely high and I’m very grateful to yourself, Matthew, Matthew and Claudia for all coming on and talking about your proposals

I think that seems to be a good point to leave it here. My guest this week has been Andrew Paynter, co-winner of this year’s Tax Policy Charitable Trust Scholarship, and we’ve been talking about his proposal to increase GST and have a refundable tax credit.

Andrew, it’s been a great privilege talking to you about that. Congratulations again. Have a well-deserved rest and onwards and upwards. I’ll watch with interest.

Andrew Paynter

Thanks, TB. I really appreciate it. Thank you for having me on. It’s been great.

TB

Not at all. Thank you. And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.