Is it time for an independent fiscal costing unit to check out parties’ promises during elections?

- An Australian case highlights the problems around removing GST from food.

- As the Government’s financial statements for the year ended 30th June 2023 are released, instead of tax cuts do we actually need more tax?

An Australian case highlights the problems around removing GST from food, and as the Government’s financial statements for the year ended 30th June 2023 are released, instead of our tax cuts do we actually need more tax?

Last week I mentioned the retirement of Geof Nightingale and I also surmised that it wouldn’t be long before we heard from him again. And sure enough, this week he popped up on Mike Hosking breakfast show talking about the various tax policies on offer. After a tongue in cheek confession that this had all given him a bit of a headache, Geof then made the very wise suggestion that perhaps it is time to establish an independent fiscal costings unit so that during an election campaign the claims of the various parties can be scrutinised impartially.

As Geof noted, this is actually something the Labour Party proposed in the run up to the 2014 election. Now, given the claims, counterclaims and accusations this week about exactly how many families would gain the maximum benefit from National’s tax proposals, maybe this is something which should be looked at again. On the other hand, someone else has also suggested perhaps we can refer them for false advertising? Probably a bit too late for that really.

Removing GST on food – a legislative headache in the making?

Moving on, the multi-party debate on Thursday night on TV1 threw up several moments of light relief, including when the leaders were asked to comment on National’s foreign buyer tax policy and Labour’s proposal to remove GST from fresh and frozen fruit and vegetables. None of the leaders thought much of either policy.

This prompted moderator Jack Tame to challenge Winston Peters, noting that New Zealand First’s manifesto proposed the removal of GST from food. (For the record, the Greens and Te Pati Māori both propose to go further than Labour on this point). It turned out, however, that New Zealand First had literally just updated their manifesto, dropping the original proposal and instead proposing it would “secure a select committee inquiry into GST off basic fresh foods. We must examine if this would deliver real benefits for taxpayers before legislating for it.”

Maybe New Zealand First’s change of tack on this topic was prompted by a recent Australian tax case. In this case the court ruled that a series of frozen food products were subject to GST and could not be zero rated (or “GST-free”, in Australia’s somewhat peculiar GST terminology). In brief, what happened was that Simplot was marketing six frozen food products such as a fried rice or pasta product, each of which contained a combination of vegetables and seasonings, as well as grains, pasta and/or egg.

The case turned on around what constitutes a kind of food marketed as a prepared meal. If they were food, as Simplot argued, then no GST applied. However, if they were if they represented a kind of “food marketed as a prepared meal but not including soup as per Australia’s GST legislation“, then it would have been subject to GST.

After an exhaustive analysis, including examining the packaging and advertising, Justice Hespe ruled GST applied. But it appears that she was none too happy with the whole process and the legislation. She remarked in paragraph 141 of her judgement

“The legislative scheme with its arbitrary exemptions is not productive of cohesive outcomes. It has left the Court in the unsatisfactory position of having to determine whether to assign novel food products to a category drafted on the premise of unarticulated preconceptions and notions of a “prepared meal”. It may be doubted whether this is a satisfactory basis on which taxation liabilities ought to be determined.”

Now that’s probably justice speak for “You have got to be kidding that we have to do this every time.” But they represent pretty wise words of warning for future drafters of any New Zealand legislation removing GST from food.

More tax, not less?

As mentioned at the beginning, a key part of the election campaign has been the various tax proposals on offer, and particularly promises of tax relief in the form of tax cuts or threshold adjustments. Each of the parties, with the exception of Labour, have something on this. But in Stuff economist and previous podcast guest Shamubeel Eaqub said of both Labour and National that they were, “pretending somehow we don’t have long term big, long term issues that we need to deal with and time is running out.” He continued, “In terms of reaching surplus they are all saying getting back to surplus is important but how do you do it while giving tax cuts and spending on things we’ve already promised ourselves?”

I echoed his comments in part by saying that I didn’t believe the politicians of the two main parties are “being serious enough about funding what’s ahead.” And I noted that it was the coming challenges in terms of the ageing population and in particular related health care and superannuation costs that had prompted the last Tax Working Group to propose a capital gains tax.

Several other commentators weighed in as well, and I’d recommend reading in particular what I thought was some fairly insightful commentary from Gareth Kiernan, the Chief Forecaster at Infometrics. He noted something that’s been a theme of this podcast for some time, that New Zealanders are already paying significantly more tax due to the issue of bracket creep because income tax thresholds had not been adjusted since 2010. Governments had benefited from inflation moving people into higher tax brackets.

But in his opinion, this policy,

“It reduces discipline on government spending and muddies the tax and welfare decision for voters. It would be more appropriate for tax thresholds to be indexed to incomes or inflation, so that if any government wanted to alter the income tax rates or thresholds, they would need to articulate the reasons for their policy.”

He also went on to note,

“..in the current environment, one might argue that there needs to be more investment in infrastructure, and more funding for healthcare, and therefore taxes need to go up to pay for that. Alternatively, one might argue that there has been considerable expansion in government spending in recent years with few results to show for it, so spending needs to be reined in and taxes can be cut to go alongside that change.”

Now, I posted a link to this story on LinkedIn and it provoked a lively debate. A couple of people came back straight away with the reasonable assertions if we cut out wasteful expenditure and enforce the tax legislation, we would have sufficient income and that we may not necessarily get a better economy or better outcomes for people by increasing tax.

What is the state of the Government’s finances?

Now, the question of how much the Government spends is quite relevant in this particular example, because this week and providing some context, the Government’s financial statements for the year ended 30th June 2023 were released.

Tax revenue was up +$3.9 billion on June 2022 to a total of $111.7 billion. But that’s actually about $3 billion less than what was projected in the Budget in May. And the main reason for that fall is that corporate tax income at just under $18 billion, is -$2.4 billion below forecast, although higher withholding taxes on interest and dividend income has somewhat compensated for that fall. The GST take was bang on with what was projected at the Budget ($28.13 billion)

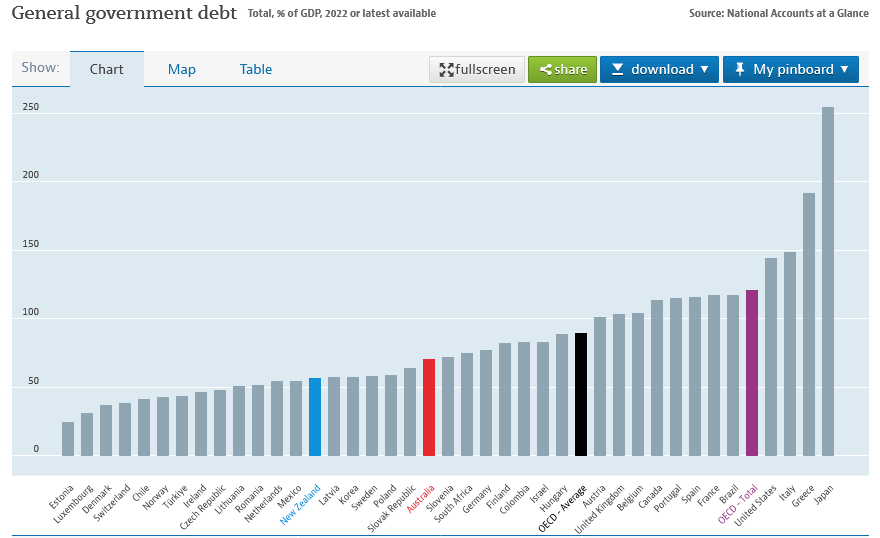

Ultimately the Government overall had an operating deficit before gains and losses of $9.4 billion. There’s been a lot of debate about government spending and core Crown expenses as a proportion of GDP were 32.2% of GDP, which is down from 34.5% in the June 2022 year. And the reason for that is the end of the COVID 19 restrictions and support that was given. Net debt is 18% of GDP, which is incredibly low by world standards.

And actually, here’s something we’ve I’ve mentioned before, but perhaps isn’t really known is that we are currently one of the few countries, according to our financials where the Government has positive net worth.

The government has net wealth of about 46% of GDP, whereas some countries such including Australia, which surprises me, are actually negative. Obviously, the big standout here is Norway, thanks to its trillion-dollar sovereign wealth fund.

The OCED measures of debt is slightly different, but general government debt is still below the OECD average. But like the commentators who are thinking we should be looking at our spending, I’m of the view we need to be investing in our infrastructure beyond roads.

But one of the things that puzzles me and it’s always brought up about government spending, it seems, is that somehow $55 million was spent on a proposed cycleway across the Auckland Harbour Bridge, which never eventuated. And then there’s a significant amount of money that’s gone into mental health, but yet doesn’t seem to have found its way to the frontline. So, I definitely agree with the view that there’s questions to be asked about the quality of our spending and how effectively it’s deployed is the quality of our public service able to deliver on what’s required? It may mean the answer is a combination that we do need more funding, but also we may actually need to invest in the capacity of bureaucrats to actually deliver.

The climate change bills arrive for Auckland ratepayers and us all

But the key point I want to come back to about the costs ahead which we’re not hearing enough about from the two main parties, is how are we going to manage the impact of climate change? This week, remember, Auckland Council has just signed off on the process of what’s to happen with a buyout of 700 properties that were red stickered following the January and February floods. That’s going to cost a total of $774 million, $387 million of which is going to come from the government.

Of note here and it’s something quite a few people have raised a red flag about, is that although insured Category 3 property owners will receive 95% of the the pre-flood market value, those who were uninsured will receive 80%. This raises the issue of moral hazard – if that’s what’s going to happen why bother insuring.

This is a big issue that I think we have to discuss: how are we going to fund all of this? Then if we are going to be in a scenario where we have to be buying out property owners, is buying out uninsured people fair for the those who have insured themselves? Is this approach a fair cost both to the people in the affected local government area and those generally in the wider population, because that’s who’s funding these buyouts.

In my view this is going to be a bigger issue because, I want to repeat again, we have so much of our wealth tied up in property, and yet property is the asset class that is most exposed to the effects of climate change. We’ve had Auckland with 700 homes, and over on the East Coast there’s another 400 homes, I believe, where this buy out process is underway.

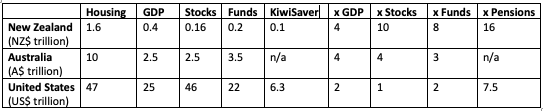

If we are going to be assisting property owners, and I believe we should, is the quid pro quo that the level of taxation on property rises? Bernard Hickey had some interesting stats in his daily Substack The Kākā around how much of our wealth relative to the country’s GDP is committed to housing. A total of $1.6 trillion, or four times our GDP, is committed to housing. But more importantly, although that’s not so out of line with other countries, it dwarfs our other investments

This royally skewed set of incentives is why our housing market is worth NZ$1.6 trillion, which is four times our GDP (NZ$400 billion), 10 times the value of our listed companies (NZX total market value of $160 billion), eight times larger than our total managed funds sector ($200 billion including NZ Super Fund and ACC) and 16 times larger than our only-very-marginally-incentivised household pension funds (Kiwisaver at $100 billion). For comparison, Australia’s housing market is worth the same four times GDP, but is worth four times stocks, three times and funds under management. In the United States, its housing market is worth twice GDP, once the stock market, twice funds under management and 7.5 times its comparable ‘subsidised’ household pensions market, which is known as 401k in America, rather than KiwiSaver.

Bernard believes, and I agree having looked at it when researching Tax and Fairness this overinvestment is a by-product of our tax settings. Therefore, if we change those tax settings around the incentive to invest in property that may change two things. One, we invest in more productive assets. And two, we raise the revenue to help deal with the coming crisis around climate change.

Will the Election change the discussion?

But at the moment it has to be said that funding the cost of climate change is not part of the two major parties’ discussions around tax, but who knows? My view is the debate around tax policy and our tax settings isn’t going to end with the Election next Saturday, it’s going to continue beyond that. In my view these issues around funding climate change will accelerate. If we can come to some form of multi-party accord on this, I think it will be better for us. But tax is politics, so don’t be holding out too much hope for agreement soon.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.