What do the father and son landlords who own more than 100 homes say about our tax system?

- Why does the New Zealand Superannuation Fund pay tax?

- ACT’s updated alternative budget dials back its tax cut package

Last week The Post published a story about Roger and Shaun Nixon, father and son landlords who by The Post’s calculation owned at least 111 residential and lifestyle properties either in person or through a combination of trusts and companies. (In total across various entities and including commercial, industrial and retail properties the pair apparently own over 300 properties across the length of the country from Kaitaia to Invercargill, including properties on Waiheke Island and Omaha, where former Prime minister Sir John Key had a holiday home).

The story was produced as part of The Post’s Mega Landlords series, and I spoke to journalist Ged Cann on the question whether many of the homes in this property empire would ever re-enter the market for sale. As I explained, at the moment there are no tax incentives such as a capital gains tax or an inheritance tax (what we used to call Estate Duties), which could force the break-up of the Nixon’s holdings.

Estate and Gift Duties were first introduced in the 1890s, and were in part designed to provide a relatively good source of revenue for the Government, but they were also a means of breaking down large estates. The Liberal government of the time was concerned about accumulation of excess wealth and the related issue of inequality which drives a lot of discussion in this area. Inequality will exist in any society, no matter what the tax setting settings are. I think it’s a by-product of any modern capitalist society. Some people are extremely able to use their advantages of natural and inherited capital to make fortunes. And by and large, I don’t have a problem with that at all.

The question we should be addressing is how far we are prepared to accept inequality and what strains it puts on our social system. It’s a difficult question to answer. We have seen a rise in inequality since the 1980s and the end of the post-war consensus where higher taxes were seen as means of equalising society. And I spoke to Ged about one of those tax tools used, Estate Duty which disappeared just over 30 years ago.

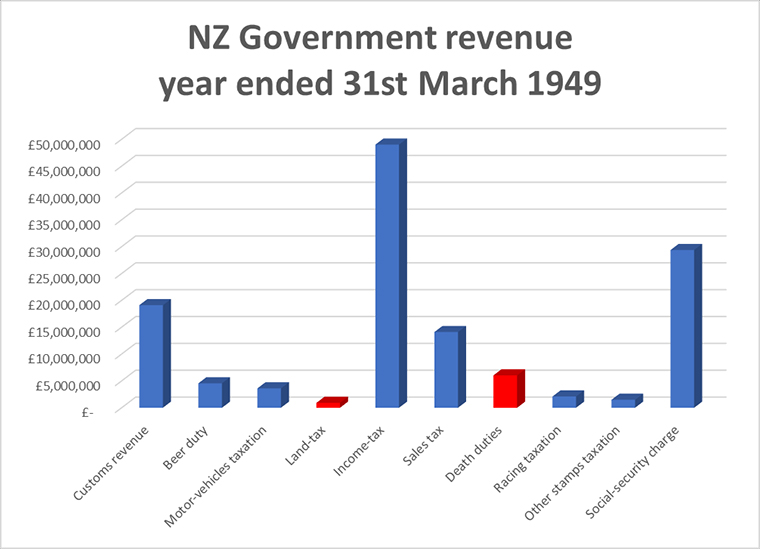

Estate and Gift duties were quite a substantial part of the tax revenue for New Zealand governments for a long period of time after the 1890s, right up until probably the turning point with the election of the First National Government in 1949. For the year ended 31st March 1949 the total amount of land tax, estate and gift duties amounted to just under £7 million of the government’s £130 million revenue. In other words, it was the equivalent of 5.3% of the total tax take for that year. If you were to project that forward, it would be the equivalent of $5.7 billion using the June 2022 numbers. So, these taxes were a very significant proportion of past governments’ revenue.

Whatever happened to Estate Duty?

Starting with the election of the First National Government the exemptions from Estate Duty were widened. This started to undermine the theory we’ve often discussed here and which I strongly support, of a broad based, low-rate approach to taxation. The broader the tax base, the lower the tax rate you can apply. And to a large extent this was the case with estate and gift duties.

But what happened was that exemptions for Estate Duties (and Land Tax) began to be expanded. And therefore, as the exemptions expand, the tax base is narrowing and then the tax take starts to fall away. And gradually, over time, the numbers diminished to the point of insignificance. Land tax was abolished in 1990 and Estate Duty reached its end point in 1992. Gift duties, for whatever reason, lingered on until 2011, before they went on the not on reasonable grounds that the barely $2 million revenue collected was far outweighed by the compliance costs.

The question that should come up is whether, in fact, the abolition of Estate and Gift Duties was a wise move on two points, firstly for maintaining a broader tax base. And secondly around this question of inequality, because Estate Duties are something that can hit estates very, very hard particularly where perhaps too much is tied up in illiquid assets, such as property. This is something I’ve seen quite a lot in the UK with the effect of what is now called Inheritance Tax.

To repeat a point I have made before, the absence of Estate and Gift Duties makes our system unusual because we don’t have a capital gains tax. (We’ve also removed stamp duty although by and large, tax theory has that stamp duties are pretty inefficient taxes. Still, they linger on everywhere else). So, we have no taxes which could be part of breaking down large estates. We have to accept whether that’s a good or bad thing.

Following IAG’s move do we need to broaden our tax base to deal with climate change?

My view is that we ought to be thinking about the question of broadening our tax base. And in that context, I’ve been thinking quite a bit on this question of estate and gift duties, because this week there was another reminder of an issue I keep raising – the growing costs of dealing with climate change.

The insurer IAG announced this week it will not offer ongoing insurance for properties in Category 3 of the Government’s Land Categorisation framework for regions affected by the floods earlier this year.

The cost of the property damage this year by those events is currently several billion and climbing. Of course, property owners are the persons that are most closely affected.

One of the doubts I have about National’s proposed foreign buyers tax is about the type of properties foreign buyers are likely to be purchasing. In Auckland, there is a growing number of suburbs where the average price is $2million. But foreign buyers aren’t necessarily wanting to buy a rundown villa in Grey Lynn or Devonport, they’d probably be looking at flashier properties in coastal areas. However, these coastal properties could now be more exposed to climate change which could be a factor in them deciding not to purchase.

Of course property owners, maybe including the Nixons, have already been affected by climate change and if they are struggling to insure their properties, they will be looking to the Government for assistance with this. And so it seems to me we are rapidly reaching a break point because we’re not taxing capital and property in particular. This is going to create a huge issue between those on one hand who have property and want government assistance when their property is flooded out or damaged beyond repair and insurance is limited or not available. On the other hand, there is a group who don’t have property and can’t get onto the ladder, who will, through their taxes end up paying for the former. This dichotomy sets up a whole social strain, which I don’t think we really want.

To repeat, the thing about this story of the megalandlord Nixons is how it illustrates to me this dilemma we have created around the taxation of capital and the preference for property as an asset class.

So why is the New Zealand Super Fund taxed?

There were some very interesting responses to last week’s commentary about the New Zealand Superannuation Fund’s (“the Super Fund”), retiring CEO Matt Whineray’s remarks on the fund’s tax status. (Thank you again to all my readers and listeners for your contributions). The question was asked, ‘Well, why does it pay tax?’ The answer, as I indicated in last week’s podcast, it was designed as such when the Super Fund was being set up prior to when it actually started investing 20 years ago this month.

As part of the creation of the Super Fund, Treasury produced a number of papers in 2000. A key paper is Pre-funding New Zealand Superannuation from June 2000.

It noted

“There are two main issues surrounding the tax status of the proposed super fund. The first of these is the tax avoidance opportunities that would be created if the fund was tax-exempt. The second is whether poor incentives would be created regarding investment behaviour.

…By making an entity tax exempt, the government effectively gives it an asset that it can trade with taxable entities. Current tax-exempt organisations such as charities have engaged in complicated schemes to take advantage of this kind of opportunity. …

We consider that making the fund tax exempt will create an opportunity for this kind of avoidance activity.”

The driving force of this paper was concern that giving the Super Fund tax exempt status would give it poor incentives. And so, the fund was set up on that basis. (It’s also interesting to note that the paper assumed the Super Fund would be contracting out most of its fund management activity. However, as we know, the Super Fund is now one of the largest fund managers in the country).

Changing the FIF rules

Back when the Super Fund was being established the tax treatment under the foreign investment fund regime was very different. There was what we call a “Grey list” that applied to investments in several countries such as the US, Australia, UK, Germany, Japan and others. Investments here were only taxed on dividends and capital gains would be taxed under the normal rules, similar to those we have now for investing in Australia and New Zealand. The amount of tax payable on these investment would not have been quite significant under those rules.

However, in 2006, proposals were introduced establishing the current Foreign Investment Fund regime which took effect from 1st April 2007. Now, the interesting thing is that I cannot see any commentary or submission to the Finance and Expenditure Committee by the New Zealand Super about the changes, although there’s plenty of commentary from the Corporate Taxpayers Group and others. As I mentioned last week, some 3,400 submissions opposed the changes, and only two were in favour. So of course, the measure went ahead.

From that point the New Zealand Super Fund started to pay a lot more tax. (In the year to June 2008 the fund had a loss of $704 million but had a net tax bill of $164 million because of the changes to the FIF regime). The effect of the FIF regime was described in a submission the New Zealand Super Fund made in 2018 to the last Tax Working Group. It said it would like to be tax exempt because as I noted earlier it’s the only sovereign wealth fund in the world which is taxed. Its tax status also creates some issues when it is investing overseas. In support of tax exempt status, the submission (signed off by then acting CEO Matt Whineray) noted.

“The fund’s tax position can be volatile depending on the performance of the fund and the contributors to that performance. This is often illustrated by our effective tax rate. For example, our effective tax rate was 3% in 2015, 96% in 2016 and 20% in 2017. The main driver of this volatility is how our physical global equities are taxed under the fair dividend rate regime. In simple terms, this means that in any given year, if our return in global equities exceeds 5%, then our tax rate will be lower than 28%. And if our returns are less than 5%, then our tax rate will be higher than 28%.”

Another interconnected issue for the Super Fund is that as so often is the case, I think Governments rather like the tax revenue from the Super Fund. However, as the Fund’s Tax Working Group submission noted if it was tax exempt it would not be forced to sell assets to pay “the Government provisional tax with the Government then turning around to pay the Fund contributions, thereby removing the need for practical work arounds in terms of offsetting provisional tax”.

As I said, way back in 2000 when they were considering the tax status of the New Zealand Super Fund, the FIF regime was very different. And I wonder whether if they had foreseen the impact of the FIF regime that was introduced from 2007, whether they might have rethought the decision to tax the Fund.

ACT Party dials back its tax cut package

And finally this week, the ACT Party has updated its Alternative Budget https://assets.nationbuilder.com/actnz/mailings/6681/attachments/original/ACT_Alternative_Budget_-_End_the_waste__fix_the_economy.pdf?1695252857 in the wake of last week’s PREFU release. Basically, in its view the state of the books means it has to dial back its tax cuts package.

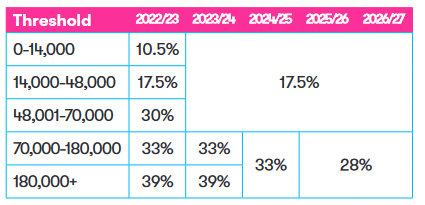

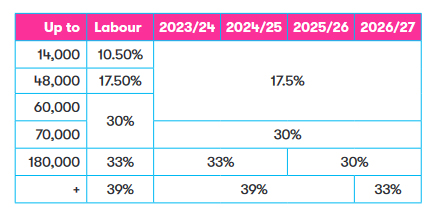

ACT’s original proposal

Act is now accepting that cannot happen but instead the top rate from 2026 will be 33%. What it has also said, and this is interesting, is that the top 39% rate will remain until then.

One of the proposals in ACT’s “Alternative Budget” is the Government will stop making contributions to the New Zealand Super Fund. But what won’t change, however, is the tax status of the fund, and it will still be taxed.

Now the ACT numbers are quite detailed, and they note that the expected tax revenue from the New Zealand Super Fund will actually drop by about $100 million over the three years to June 2027 period because of lower Government contributions. (Incidentally, in measuring debt-GDP ratio ACT’s Alternative Budget excludes the $65 billion value of the NZSF which rather unfavourably distorts the ratio).

ACT also proposes winding back the KiwiSaver member’s tax credit (the Government contribution you receive if you make contributions of at least than $1,043 a year), for higher income earners. Instead, it will be capped at 5% of a participant’s taxable income. The maximum subsidy amount will reduce by 3% per dollar of income above $48,000, reducing to zero by around $65,000.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.