The departing CEO of the New Zealand Superannuation Fund questions its tax status.

- Inland Revenue announces a review of the rules relating to the donation tax credit.

- A new policy framework for managing debt owed to the government.

- PREFU’s $5 billion hole in the government books no one is worried about.

Tax continues to feature heavily in the Election with the ongoing debate over the validity or otherwise of National’s proposed foreign buyer tax. But away from the election, it has been a busy week in the tax world. By far the most interesting story, partly because of its source, but also how it speaks to the structure of our tax system, is the commentary from Matt Whineray, the outgoing chief executive of the New Zealand Superannuation Fund (NZSF), about the fund’s tax status.

In an interview with the New Zealand Herald’s Markets with Madison, he remarked on the NZSF’s tax status, noting that since the fund began investing in 2003, it had paid nearly $10 billion in tax, including $2.2 billion for the year to June 2022.

This makes it by far and away the largest single taxpayer in the country. He thought this was rather nonsensical and that the fund really should have tax immunity status in line with many other sovereign wealth funds around the world, (including ACC and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, both quite substantial investment funds). “My wish would be that we didn’t pay tax because I think that would solve a few issues.”

A nonsensical money-go-round?

He questioned the practice of the NZSF returning money to the Crown in tax, and the Crown in return contributes to the fund annually. “If I take my wallet out of this pocket and put it into this pocket, I haven’t got richer.” The problem, in his view, was exacerbated when the Crown stopped contributing to the fund completely, as it did for almost a decade between 2009 and 2017.

It’s interesting to hear such commentary from Matt Whineray, which highlights an anomaly about the NZSF, in that it is a sovereign wealth fund, but it pays tax, which is highly unusual around the world. In fact, I’m not sure there are any other sovereign wealth funds which do pay tax. (It’s an issue Whineray’s predecessor Adrian Orr also raised, as has Whineray previously).

Now when the NZSF was set up 20 years ago, the rationale behind it paying tax was this would help it make sound investment decisions based on investment principles and not by tax considerations. And in a broader sense, that’s not unreasonable. I always tell my clients, don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog. Think in the longer-term investment and returns rather than the short, potentially shorter-term tax implications.

A “Fair” Dividend Rate?

Someone else this week commenting on this question of the tax status of savings was financial planner Rachelle Blanch speaking to Susan Edmonds of Stuff.

Rachelle thought it was time for a review of the Foreign Investment Fund (FIF) regime, particularly in relation to how it applies to portfolio investment entities such as KiwiSaver funds. Now, the FIF regime and the Financial Arrangement regime are the two main reasons the NZSF pays so much tax. That’s because both regimes tax unrealised gains and there will be substantial unrealised gains in investment funds.

As the story in Stuff noted, under the FIF regime KiwiSaver funds and the NZSF must use what’s called the fair dividend rate in respect of their overseas shareholdings. This deems 5% of the opening market value of the investments held at the start of the tax year to be taxable income. Now obviously as KiwiSaver funds grow in size, and they diversify out of the New Zealand market as the NZSF has done, then the amount of tax payable as a consequence of the FIF regime will increase. However, unlike individuals or trusts, who can switch methods to mitigate the impact of a drop in values of some of investment funds by adopting what we call the comparative value method, KiwiSaver funds and the NZSF can’t do that.

How much tax is payable under the FIF regime is not at all clear. The NZSF is probably the only entity which can give a pretty accurate gauge on that. But to give you some idea of the total tax that might be payable – the Financial Markets Authority produces an annual report each year on KiwiSaver funds, and it notes that for the year to June 2022, KiwiSaver funds paid over $256 million in tax for that year. Remember in the same period, the NZSF paid over $2.2 billion.

Rachelle Bland has raised a very good question as to whether, in fact, this is an appropriate tax policy response where people have long term savings. She describes it as effectively a capital gains tax. Another way of looking at this, and it’s how I describe it whenever explaining the regime to overseas clients, is that it operates as a quasi-wealth tax.

As I said, there’s no mitigation for significant falls in stock markets. Unlike a capital gains tax regime which taxes on a realisation basis you can decide to realise capital losses and offset them against capital gains. You can’t do that under a FIF regime. Therefore you have this situation where the value of investments are falling but you’re still paying tax on the value of those investments. And that’s been the scenario for quite a few funds over the past 12 to 18 months.

What about a tax exemption then?

It’s not surprising then that quite apart from this anomalous washing – as Matt Whineray referred to the process of cycling funds from the Crown to the NZSF and then back in the form of tax – there’s also calls for some form of tax exemptions for KiwiSaver funds. You see such tax exemptions around the world for other pension schemes. New Zealand is yet again, a bit of an outlier here. The reason such exemptions were taken away in the late 1980s is they are costly. However, in overseas jurisdictions where tax exemptions apply to pension schemes withdrawals are taxed, whereas in our system we apply what we call a tax-tax-exempt approach where the contributions are made out of after-tax income, the schemes are subject to the ordinary taxation rules, but any withdrawals are exempt.

What’s the most effective approach? Well, that’s still a matter for debate. But one thing to keep in mind is that tax does have an impact on the long-term return of funds. Now, whether anyone is going to do anything about this is very questionable. The FIF regime in its current iteration has been in place now since 1st April 2007, and it generally works pretty well. The rules were very controversial when they were first proposed. There was an absolute storm of protest when they were first proposed, with Parliament’s Finance and Expenditure select committee receiving 3,400 submissions against the introduction of what is now the FIF regime, and only two in favour. In the face of this criticism, they were actually reshaped and now everyone has got used to working with the regime.

And this perhaps is the critical point. Governments appreciate the tax paid by the NZSF and KiwiSaver funds. The total tax for the year ended 30th June 2022 from those two sources probably represents just about 2% of the total tax take for that year. Therefore, changing the tax treatment for the NZSF and for KiwiSaver Funds would be an expensive move even if as a trade-off the Government might not then need to make any more contributions to the NZSF.

Wrong sort of investment signals?

Given the short-term pressures at the moment on the Government’s books, I think any move in this area is not going to happen. But I also consider it underlines a scenario where we’re prepared to tax savings under the current tax system, but generally whole asset classes, such as property, the bright line test excepted, are outside the tax net. This treatment sends an investment signal which politicians aren’t prepared to address.

Where does investment get directed? The evidence we have points to it being directed into relatively unproductive residential property investment as opposed to the likes of KiwiSaver funds, which will invest in productive businesses.

The discussion we’re not having

Now, this is a discussion we’re not having at the moment about how the tax system and investment interacts. As I’ve said in previous podcasts when you consider National is proposing removing commercial property depreciation on non-residential property again, (as is Labour for its part) in both cases to fund some form of tax cuts this to me sends the wrong signals. We’re basically directing funds away from investment in our economy into consumption.

But this is not a discussion we’re going to have because although politicians quietly recognise that whatever we the electorate might say about the impact of tax in the back pockets – and we’ll happily all take tax relief, tax cuts, how you phrase them – we also like the services tax provides. So, this dichotomy exists. We’ve got to maintain services as far as possible but not want to pay for them. But as I’ve said repeatedly, I think the under taxation of capital is an unsustainable position long term.

Donations tax credit review announced

Moving on, Inland Revenue just carries on carrying on regardless of whether the Government is out campaigning. It has been busy churning out quite a lot of interesting material. But two particular initiatives happened this week.

Firstly, on Friday, it announced it is going to undertake a review of the rules relating to the donations rebate rule. This review is part of the Regulatory Stewardship programme required of all state agencies in respect of the rules they administer. In this case, a review is going to assess whether the donations tax credit regime is operating effectively, is achieving its policy intent, and how it compares internationally.

Inland Revenue will open up consultation with an aim of undertaking this review and completing a report, setting out its findings as well as any recommendations by mid-2024. Interested parties will be contacted on this. I imagine you can expect the Charities Commission, some more major charities, would be approached. I think the main accounting bodies, together with the New Zealand Law Society will also be approached for comment on the matter.

A fairer Government debt policy framework?

The second Inland Revenue initiative and probably something that’s going to have more immediate impact ties into the rather strange case we talked about last week involving the Nelson woman who got herself into a whole heap of trouble with Inland Revenue and decided the best way out of avoiding a $365,000 tax debt was to sell her property worth $845,000 to a UK company. The Official Assignee took a dim view of the idea and obtained a court order striking the sale down.

Leaving aside the oddities involved the case is relevant for the important question of tax debt and other debt that’s owed to the Government. According to the New Zealand Herald story reported last week, as of 30th June 2023 Inland Revenue is owed nearly $5 billion.

Now, both the Tax Working Group and the Welfare Expert Advisory Group took a look at the question of debt owed to the Government as part of their reviews, and they recommended there should be some form of all of government approach to debt. Firstly trying to prevent debt arising with the Government, but also how each relevant government agency responds and manages that issue.

Consequently, a policy framework for debts the Government is owed has now been developed and has been signed off by the Cabinet. Inland Revenue this week released its report and background details on this framework.

There’s quite a bit to consider in here, not just the $5 billion Inland Revenue is owed but the other debts built up, primarily with the Ministry of Social Development and also with the Ministry of Justice.

According to this report, at present 762,460 New Zealand residents collectively owe $4.68 billion of debt to these three agencies – Ministry of Social Development, Inland Revenue and the Ministry of Justice. More than a quarter of these persons owe debt to two or more agencies and 6% that’s over 45,000 people owe a debt to all three. Furthermore, around three quarters of this debt, so that’s well over $3 billion, is owed by low-income individuals, many of whom rely on government benefits as well. 13% or just over 99,000 people owe more than $10,000 to the Government.

More than 85% of those who do owe a debt have owed it for more than a year and about 45% cent, an incredible number, have owed debt for at least four years. Finally, Māori and Pacific people are overrepresented in almost all categories of debt a sadly quite typical issue.

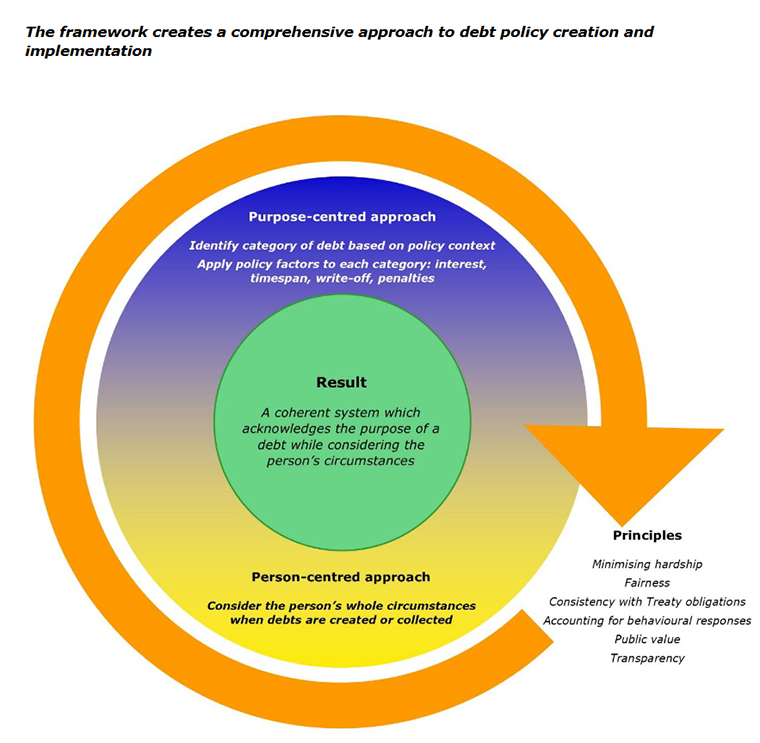

The debt policy framework is trying to ensure is that debt recovery is fair and effective and avoids exacerbating hardship. And above all, it aims to prevent debt occurring in the first place and not exacerbate issues.

There are three main parts to the framework. Firstly, a set of overarching principles for creating and managing debt. Then secondly, a purpose centred approach which classifies debt into different groups according to the policy purpose and discusses how different settings might be appropriate for some purpose and others. And then finally, what’s called term to person centred approach, which takes into consideration the personal circumstances, with focus on consideration of financial hardships, as I said.

These debt issues tend to exacerbate and build on each other leading to a circle of despair. $10,000 of debt doesn’t sound like a lot, but for very low-income people it seems like an insurmountable mountain.

Anyway, this framework has been signed off by the Government after feedback from quite a number of interested agencies. For example, the Citizens Advice Bureau, the Methodist Alliance, the New Zealand Council of Christian Social Services, the Salvation Army, and a whole range of other non-governmental organisations. Hopefully this feedback will build a better framework for the practice of managing this debt.

Good but Inland Revenue also needs to do its part

I welcome this initiative, but I also think that as part of it, Inland Revenue needs to be also considering its approach to debt management, such as the effectiveness of the late penalty regime, and how efficiently it is on top of managing debts, because if the debts get away from people, they just give up. That’s what my experience has shown time and again and it’s also what Inland Revenue has experienced.

I think it’s still a good step forward, particularly, in trying to bring a coordinated approach because there’s nothing more infuriating to someone who might be unlucky enough to find ourselves in a position of debt with two or three agencies, and finding that the approach taken by each of those agencies is different.

The Tax Working Group recommended a single Crown agency to manage current debt should be established to deal with this issue. That does not seem to have been part of these recommendations at the moment, maybe it might be picked up at a later stage. Nevertheless, it’s a step forward in the right direction and we’ll hope that it starts to address these issues of managing the debt fairly and efficiently for people.

The $5 billion PREFU hole no-one is worried about

And finally, this week, back to the Election. We’re still hearing plenty about tax in the election campaign. Politicians are all out on the trail telling us everything that’s going to happen or not happen. This week the formal opening of the government books happened with the release of the Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Update (PREFU). There was plenty of differing interpretation about the state of the government’s finances going forward.

But there was a wonderfully interesting little snippet which Newsroom picked up on, and that was the impact of next year’s Matariki public holiday. Matariki always falls on a Friday, and next year it falls on 28th June, which is the last working day of the fiscal year to 30th June 2024. And because of that, the cash that would come in on that day, which represents about $5 billion of GST and provisional tax won’t actually hit the Government’s coffers until the following Monday, which is 1st July and the start of the following tax year. So, on the face of it, the Government’s going to be $5 billion short of cash for the current year ending 30th June 2024.

As a Treasury spokesperson said, “This public holiday effect is expected to affect the Crown’s tax receipts but not tax revenue, since Inland Revenue will calculate accrued tax revenue as at 30 June 2024 as it normally would at any other year end.”

And for the record, this won’t really affect individuals because we file tax returns to 31st March each year. Furthermore, Inland Revenue won’t penalise people for making a payment on 1st July, the first working day after it was due because Inland Revenue hasn’t switched over to a seven-day banking. So nice quirky little story to end the week.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.