Change on the way for GST recordkeeping requirements

- Change on the way for GST recordkeeping requirements

- A clear-eyed dissent by a Supreme Court justice

- Tax revenue exceeds $100 billion for the first time

Over the next few months, GST registered businesses will receive a stream of information from Inland Revenue explaining new recordkeeping requirements for GST purposes, which will take effect from the 1st April next year. These changes relate to what information needs to be shared or retained to support GST input tax claims.

These changes are permissive in nature, and existing invoicing practises and systems which are compliant with the previous GST rules will still remain compliant with the new information rules. The new rules are less prescriptive about the information required to support a GST input tax claim.

The key purposes of these changes are to try and reduce compliance costs for businesses and facilitate the introduction of e-invoicing. The changes will be done by way of requiring the supplier and recipient of a taxable supply to retain a minimum set of information relating to that supply. The current rules, which required formal documents such as tax invoice, credit notes, debit notes etc. to support input and output tax will be repealed.

One of the most noticeable changes will be that there will no longer be a requirement for an invoice to have the words ‘Tax Invoice’ in a prominent place. Tax invoices will now be caught termed ‘taxable supply information’ and the former debit and credit notes which had to be issued when a correction was made, will now be termed ‘supply correction information’, which is better terminology as it actually reflects what’s going on.

There are also changes to the buyer credit created tax invoice regime which are now called ‘buyer created taxable supply information’. And these changes have already come into effect and actually are pretty helpful because you now no longer need to get Inland Revenues permission to operate the buyer created taxable supply information.

There will be a minimum set of information required to be retained in business records under the new rules for a taxable supply. According to Inland Revenue these rules are generally consistent with the requirements of commercial contract law relating to invoicing and recordkeeping. The requirement to hold a tax invoice in order to claim an input tax deduction is now replaced with the requirement to have business records showing that GST has been borne on the supply.

Now key information for both a supplier and a recipient of a supply of goods or services is that of, ‘supply information’. This includes, at a minimum, all the following information:

– the name and registration number of the supplier,

– the date of supply,

– a description of the goods or services, and

– the amount of consideration for the supply.

Helpfully, the low value transaction threshold for taxable supplies has been increased from $50 to $200. And that is part of a drive to simplify recordkeeping requirements for a large number of low value transactions.

There are now three value thresholds for the general meaning of taxable supply information and the information requirements for each of these are mutually exclusive. The thresholds are:

– Supplies exceeding $1,000,

– Supplies between $200 and $1,000,

– and then those for supplies not exceeding $200.

All these changes come into effect from 1st April next year, although, as I mentioned, the changes to the buyer created taxable supply information have already taken effect. As noted, existing systems will still remain compliant. So, there’s no need to dramatically go out and change everything to meet the new requirements. Inland Revenue will continue to release information about the changes over the coming months.

Supreme Court justices display worrying lack of tax knowledge in key decision

Last Friday, the Supreme Court released its decision in the case of Frucor Suntory New Zealand Ltd v Commissioner of Inland Revenue. This case has been watched with some keen interest by tax professionals. It relates to a series of transactions that took place in 2003, as a result of which DHNZ, a predecessor to Frucor Suntory, claimed interest deductions totalling $66 million in respect of an advance made by Deutsche Bank.

Inland Revenue sought to restrict the interest deductions totalling just over $22 million dollars claimed for the 2006 and 2007 income years on the grounds the funding arrangements constituted tax avoidance. Just for good measure, they also levied shortfall penalties totalling $3.8 million for the two years because they considered the tax avoidance was abusive.

The case reached the High Court in 2018, which ruled in favour of Frucor which was something of a surprise at first sight for those not familiar with the facts. Inland Revenue unsurprisingly appealed the decision and in 2020 the Court of Appeal held that the deductions did represent tax avoidance. However, the Court of Appeal did not accept the criteria for shortfall penalties had been met, so both parties were unhappy with their decision and naturally both appealed to the Supreme Court.

Last Friday it ruled by a 4 to 1 majority that the arrangement did represent tax avoidance and the shortfall penalties were correct as the tax position adopted by DHNZ (Frucor) was unacceptable and abusive as DHNZ acted with the dominant purpose of obtaining tax advantages.

Now, in some ways, the Supreme Court’s ruling is unsurprising. New Zealand courts have taken a fairly hard line on what is perceived as tax avoidance for the last 15 years or so. But there’s still a number of points of interest here. Firstly, you will note the length of time involved: the transaction happened in 2003. The assessments, which are the subject of the appeal, were for the 2006 and 2007 tax years. And there’s nothing I’ve seen yet explaining why it took nearly so long to reach the High Court. Under the principle of justice delayed is justice denied it’s concerning to see the amount of time involved.

Then there is the imposition of shortfall penalties, which seems harsh. If you are taking something all the way to the Supreme Court, you know you’re arguing on the margins. Nine judges looked at the matter and five said no shortfall penalties were appropriate. The only four that did think they were appropriate were the ones that mattered most because they were all on the Supreme Court. And you often see this in in court cases, the lower courts rule one way and then the Supreme Court says, nope, it’s the other way, and that’s the end of it.

But most interesting of all is the strong dissent by Justice Glazebrook in the Supreme Court now. Dissenting justice judgements are often very interesting reads, and I suspect Justice Glazebrook’s will be read and examined in quite considerable detail, given what she rebutted completely the principles adopted by the other four justices. Just for the record it’s worth noting that before she became a judge back in 2000, Justice Glazebrook was a tax partner in a law firm. She’s actually one of the co-authors of a book on the financial arrangements regime. In fact, the first edition, published back in 1999, is still had not yet been updated. So she’s got a good background in tax.

But the paragraph, I think is going to raise a few eyebrows is the penultimate one of her judgement.

[247] “The majority say that the dominant purpose of the arrangement in this case was to reduce the tax liabilities of Frucor. This despite the fact that the whole reason for the restructuring was to ensure that Danone Asia did not incur tax liabilities in Singapore, unlike the position before the refinancing where direct debt funding was provided by Danone Finance. Given that, before the refinancing, Frucor was deducting interest payments roughly equivalent to the amounts it claimed deductions for under the current arrangement, it is difficult to see how its purpose could have been to achieve a result it was already receiving (deductibility of interest) and thus difficult to see its dominant purpose as being to reduce its tax liabilities or to achieve an illegitimate tax advantage in New Zealand.”

Now that’s quite some paragraph, I have to say I don’t think I’ve seen for a while a judgement where you’ve got such completely opposite views on between the judges.

You often see differences in interpretation, but here there’s a very marked difference on the core of the case. Justice Glazebrook has questioned how it is tax avoidance in New Zealand when you consider that the real purpose of the restructure was to resolve a tax problem for the offshore parent.

It will be interesting to see feedback from other, more experienced legal practitioners and tax specialists who work in this space about this decision. As I said, I find Justice Glazebrooks dissent there quite strong, and I suspect it will generate quite a bit of commentary.

Hiding the effect of fiscal drag

Moving on, the Government published its financial statements for the year ended 30th June 2022 on Wednesday. As you no doubt are aware by now these turned out to be better than expected and have generated quite a bit of chatter around the overall tax burden and the implications for next year’s election.

From a tax perspective, what’s interesting to see is the strong rebound in company income tax. The forecast in the 2021 Budget was that corporate tax would be just over $13 billion. By the time of this year’s budget in May the estimate had risen to $17.25 billion. In fact the total for the year was just under $19.9 billion.

For individuals the tax source deduction payments (PAYE) are up. Two factors are at play here: the well-known one of fiscal drag or bracket creep which means as people’s wages rise, they cross tax thresholds and their tax increases. On top of that, you’ve got the introduction of the new 39% tax rate. Those two combined, according to the commentary to the financial statements, represented about $1 billion of extra tax.

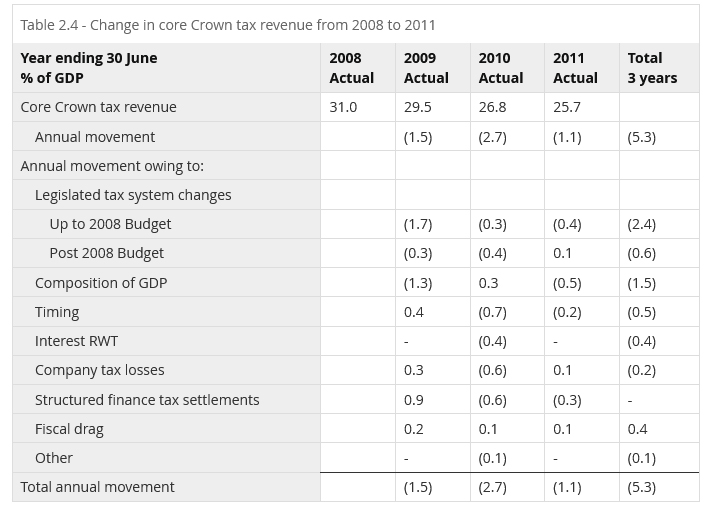

You have to dig very hard to find out what is the effect of bracket creep or fiscal drag, because that’s not being reported in the budget statements. You can draw your own conclusions as to why that is so. But we do know that when it was included in the 2012 Budget the effect was between 0.1 and 0.2% of GDP.

At a rough guess the current effect of fiscal drag would be somewhere around $500 Million a year.

The GST take rose to $43 billion gross with the net GST for the year being $26 billion through. Overall, as I mentioned at the top of the podcast, tax revenue, including indirect taxation, exceeded $100 billion for the first time at just under $107.9 billion.

So, lots of excitable chatter about what that means politically for tax cuts and other changes. Speaking on RNZ’s The Panel yesterday afternoon, (about 12 minutes in) I reiterated what I have said elsewhere that we need to do more about the tax brackets at the bottom end because that’s where the effects of fiscal drag are the hardest. The non-indexation of income tax and Working for Families thresholds means there are people on say $50,000 a year & receiving Working for Families who are on an effective marginal tax rate of 57%.

Roasting the idea of GST exemptions

Obviously what went on over in the UK has also attracted attention. This week the UK Government abandoned its higher rate tax cuts in the face of extreme political pressure from all sides, including Conservative MPs. It’s been very interesting and entertaining to watch a really classic example of the “Order, Counter-order, Disorder” maxim. And I do wonder how Prime Minister Liz Truss and her [Finance Minister] Kwasi Kwarteng are going to survive.

And finally, speaking of the UK, one of the things that comes up in discussions about how do we help with the cost of living is a not unreasonable suggestion on the face of it, to remove GST on certain foods. Now I’m in the GST purist camp here. I don’t believe we should do that. To repeat a point I’ve made several times, if you are trying to help people who have not enough income, give them more income. Any changes to the GST system such as zero-rating food benefits everybody and therefore are also more expensive as a consequence. And that idea of targeted assistance is consistently noted by the Tax Working Group and also the Welfare Expert Advisory Group.

But there’s another reason why you wouldn’t want to do it unless you wanted some inadvertent laughs. And that is the absurdity of the distinction which happens at the point where you are trying to determine whether a particular product is zero rated or standard rated. Now, Britain, with its VAT (value added tax) regime, has produced a number of very entertaining cases on this. I think people may be aware of the Max Jaffa case, which involves the distinction between a biscuit (standard rated) and a cake (zero-rated).

But this week I was alerted to one which is even more spectacularly hilarious, and it involved marshmallows of unusual size, which really sounds like something a line from The Princess Bride. A VAT tribunal case ruled that marshmallows of an unusual size are 0%, but standard sized marshmallows were standard rated at 20%. As one commentator noted, it’s sometimes very difficult to decide whether a VAT case is indistinguishable from satire.

This case involved a £470,000 dispute between Innovative Bites Ltd and H.M. Revenue Customs about the product “Mega marshmallows”. The VAT tribunal ruled that mega marshmallows were zero rated because they have to be roasted before they could be consumed and therefore not a standard rated snack.

On that bombshell, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!