- Terry looks back on the big tax issues of 2022.

- After all, taxes are what we pay to get, maintain and keep a civilised society

A war, inflation, a proposed Tax Principles Act, dramatic U-turns and the Trusstastrophe. 2022 has been quite the year and I’m certain I’m not the only one whose predictions finished up wide of the mark.

Back in January, I saw three main themes for the year. Firstly, the ongoing response to COVID 19 and what new fiscal support will be offered. As part of this, the question of inequality and the taxation of capital would be on the agenda. Secondly, international tax reform and progress in the deal announced in October 2021. And finally, with Inland Revenue, how it was going to administer the tax system in the future.

Well, on the first there was a new COVID support package announced shortly afterwards in February, which ran through until May. However, although COVID is still very much around, the Government’s focus has rapidly shifted to dealing with a cost-of-living crisis in part, the result of COVID 19 and supply chain issues and the spike in oil prices after Russia invaded Ukraine.

By the way, as for financial support for COVID, only the Leave Support Payment Scheme, which pays $600 per week, remains available

Now, this is the year the details of the international tax deal announced in October 2021 were meant to be worked out, so everything would then be ready for implementation next year. Instead, it ran into a series of obstacles which has delayed this implementation until 2024 at least. Fortunately, however, this week a key obstacle has been removed, after first Hungary and then, following some last-minute shenanigans, Poland, dropped their objections to the deal. This enabled the EU to unanimously agree to implement Pillar two of the OECD proposals. This will impose the minimum corporate tax rate of 15%, which will apply to all national and domestic groups with combined annual turnover at least €750 million.

Overall, although progress is being made, it is at a slower pace than was expected back in 2021, and I would expect that will still continue to be the case next year. In fact reading the tax press, some are beginning to wonder if it will ever happen. But we will see.

Inland Revenue and the Cost of Living payments

After completing its Business Transformation programme, I expected Inland Revenue to turn its attention back to how the tax system is run. And certainly, at the start of the year there was a quite a bit of activity in this area with a particularly useful paper prepared by business New Zealand on the matter. However, the topic dropped off the radar in the wake of the cost-of-living crisis, which somewhat ironically then put the spotlight on how Inland Revenue operates.

In May’s Budget the Government announced a Cost of Living payment of $350 to be paid in three monthly instalments starting on 1st of August. To say there were a few teething issues would be one of the understatements of the year. Although mistakes were inevitable, given that were potentially over 2.1 million recipients, right from the outset, Inland Revenue seemed to be struggling to manage the delivery of the payments.

As has been reported, quite significant numbers of ineligible recipients and a large number of whom were outside New Zealand, had received payments incorrectly. And Inland Revenue also acknowledged there had been a systemic problem in respect of one group of 12,000 recipients.

Inland Revenue does now appear to have got on top of the issue of identifying the correct recipients of the payments. By the time the third payment was made on 1st October, the number of payments, compared with the first instalment in August had reduced by 96,000.

Inland Revenue now calculates that between 70 and 80,000 people may have incorrectly received a cost of payment and has now begun contacting this group about those payments.

Given payments were expected be made to 2.1 million people, some mistakes were inevitable. It is however, of concern that there were systemic issues identified. It’s arguably more problematic that Inland Revenue required by its own estimate, 750 staff, almost 20% of its current staff, to process those payments. This, combined with persistent rumours about now frequent overtime indicates potentially serious under-resourcing issues at Inland Revenue and that is something we will be keeping an eye on going forward.

The Cost of Living payment was one of the few surprises in May’s Budget. Grant Robertson chose again to do nothing about increasing thresholds, which, although tax rates were changed on 1st October 2010, the actual thresholds at which those tax rates apply, haven’t actually been adjusted since 1st October 2008. The theory behind the Cost of Living payments were that they were more targeted than raising the thresholds. But as we’ve just discussed, administrative errors by Inland Revenue meant that the payments attracted more controversy than anticipated.

Politics trumps tax policy, again

That said, the controversy around the Cost of Living payments paled beside the reaction to a proposal in the August tax bill to raise GST on management fees paid by KiwiSaver funds. On the face of it this was a routine tax measure designed to tidy up what was an unclear tax treatment and would not have taken effect until 1st April 2026. But it was expected to realise an estimated $225 million a year and then a political storm erupted once the accompanying Regulatory Impact Statement revealed that on the assumption the increase in GST would be fully passed on to KiwiSaver fund members, KiwiSaver balances would be reduced by an estimated $103 billion by 2070.

The Government rapidly decided to retreat, and the offending proposals were withdrawn inside 24 hours, which is a quite unprecedented move. It is one of the clear cases of politics trumping tax policy because once the dust has settled, the issue the matter was trying to resolve is still to be addressed. I suspect that whoever tries again might think about addressing criticism by using the funds raised to either restore the fee subsidy of $40, which was withdrawn in 2009, or adopting one of the Tax Working Group’s proposals for minimising the effect of tax on KiwiSaver funds of low-income earners.

The Trusstastrophe

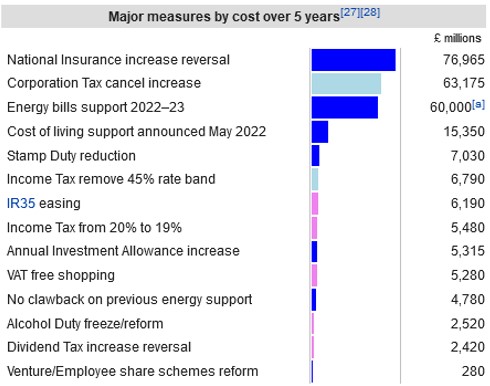

That controversy and U-turn was, quite frankly, nothing compared with what might politely be described as the Trusstastrophe (I’ve seen ruder descriptions) which happened barely a month later in the UK. To recap new Prime Minister Liz Truss and her Chancellor of the Exchequer, (finance minister) Kwasi Kwarteng decided to go for broke with a bold tax cutting mini-Budget in September. This proposed significant tax cuts, primarily the reversal of a proposed corporation tax increase and the removal of the 45% tax rate on the income tax rate. This provoked a massive run on the Pound and more worryingly in the gilt markets, the UK Government’s bond market.

Within four weeks, no fewer than seven of the tax cutting proposals were gone and shortly afterwards so too were Kwarteng and Truss to become footnotes in history. Truss becoming the shortest serving prime minister in British history. (Remarkably, Kwarteng is only the second shortest Chancellorship in history, after Iain Macleod who died in office after just 30 days).

What Kwarteng proposed

What eventually transpired

But if that was all great fun to watch from this side of the world, Truss and Kwarteng’s dramatic fall actually had a knock-on effect here. Arguably the most controversial proposal was the withdrawal of the highest 45% income tax rate band, it highlighted how a disproportionate amount of the proposed tax cuts would have gone to relatively few people. In the wake of the fallout, National here felt compelled to announce it wouldn’t go ahead with its proposed abolition of the 39% tax rate in its first term if it forms the Government after next year’s election.

There was also something else amidst the mayhem which didn’t attract a lot of attention. There were no attempts at all by Truss and Kwarteng to reduce capital gains tax or inheritance tax. In fact, Kwarteng’s successor as Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, has actually increased the tax on capital gains by reducing the annual tax-free allowance from its current £12,300 steadily to £3,000. This is an interesting insight into the relative states of the tax systems in the UK and here. The UK system even when being managed by bold tax cutters left alone the taxation of capital. Whereas as we know here, the taxation of capital is a perennial problem.

A Tax Principles Act?

It was in part to this issue that David Parker, the Minister of Revenue made a very interesting speech in April in which he proposed a Tax Principles Act across by which the system could be judged, regardless of the Government in charge. It’s well worth reading again the proposals, but we have not seen anything regarding the proposed bill which at the time he suggested would be coming out this year. Given how the Government reacted to the GST on management fees issue, I think it’s probably likely we won’t see this at all until next year, if Labour is re-elected and forms the next Government.

A constant theme of this podcast is around taxation of capital, because there’s a lot going on in the world in this space. As we just mentioned, the UK despite bold tax cuts, wasn’t prepared to make changes to the taxation of capital. Over in Ireland, the Irish Government asked a Commission on Taxation and Welfare to report on the Irish tax and welfare systems. Its final report published in September, made 116 recommendations, one of which was that the overall yield from wealth and capital taxes, including property, land, capital acquisitions and capital gains taxes should increase materially as a proportion of overall tax revenues.

And this is one of the areas we think New Zealand is out of sync with global trends. But the politics are very difficult. It’s easy to say what’s needed as a tax consultant, but politicians want to be re-elected and they have to deal with the political fallout. But whenever I do address this topic, it always provokes a lively discussion.

Top Five most read transcripts

It’s interesting to look at what are the most read transcripts and most listened posts and try and pick a common theme. They’re actually surprisingly different. By far the most read transcript for the year was when I discussed an interpretation statement on the application of land sale rules to co-ownership changes and changes of trustees. Interestingly, this was one of the top five most listened podcasts.

The Budget special was the second most read transcript for the year. At number three was when I discussed extended reporting requirements for trusts. (In that episode I also warned about the risks of mis-understanding the UK’s remittance basis rules after then Chancellor, and now Prime Minister Rishi Sunak became embroiled in a scandal).

The consistent theme emerging is about the taxation of property/wealth and that’s the case for the fourth and fifth most read transcripts. The fourth-place transcript covered a Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s Analytical Note on the housing market in an international context. The RBNZ note compared our housing market with several other developed markets and suggested that favourable tax settings have not helped the housing crisis.

In the fifth-place transcript I looked at the question of wealth and windfall taxes. Certainly, the comment section gets pretty lively whenever I make a suggestion that maybe we do need to change tax settings around the taxation of capital, such as introducing the fair economic return that Associate Professor Susan St John and I have been talking about for some time.

Top podcast tracks

With podcast listeners the top five is slightly different. The most listened to podcast for the year involved the proposed income insurance scheme, which has slipped under the radar although it’s still progressing in the background. Housing and countering tax avoidance was also in the top five podcast tracks for the year but only the episode covering the changes in ownership appeared in both top five lists.

Time for a more open discussion on tax?

As I said, whenever we deal with the taxation of housing, that pushes a few buttons which is sometimes amusing to see, but inevitable. But debates about what we tax aren’t going to go away. We’re going to see them more so next year being an election year. I do think we need to be asking a lot more about why we’re raising the tax – this point frequently comes up in the comments to a transcript.

This is important because one of the things that is emerging is the longer-term trends for the tax-take relative to the demands and pressures on it, such as rising superannuation costs. Those aren’t being very publicly discussed, but they’re very clearly being pointed out in Treasury’s report on Wellbeing and particularly in He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, its combined Statement on the Long-Term Fiscal Position and Long-Term Insights Briefing. But the Government doesn’t really want to talk about capital gains taxes at all. When Inland Revenue was preparing its Long-Term Insights Briefing it was specifically told not to consider the impact of capital gains tax.

I think politicians have deliberately, if understandably proscribed debate on the matter. But the fact is those debates aren’t going to go away. Tax systems evolve over time and these issues are going to need to be discussed because ultimately if “taxes are what we pay for a civilised society”[1], they also meet the demands of the economy and society at that time. If tax doesn’t change or adapt to meet those needs we have future problems brewing.

And on that note, that’s all for this week and for 2022. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you to all my listeners and readers and for all the feedback I greatly appreciate it even if we don’t always agree.

Until next year kia pai te Kirihimete, have a great Christmas!