- Vivien Lei introduces her award winning tax reform idea to introduce weighting factors into environmental tax loads, ensuring the full costs are brought into business decisions and nudging behaviour away from polluting outcomes

This week, I’m joined by Vivien Lei, this year’s winner of the Tax Policy Charity Scholarship. Vivien, and other entrants were invited to propose significant reforms to our current tax system or analyse potential weaknesses and unintended consequences from existing laws and propose changes to address them.

Topics for consideration were environmental taxation, tax administration or the powers granted to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to collect information for tax policy purposes. Vivien won with her proposal to change Aotearoa-New Zealand’s environmental practises with impacts weighted taxation.

Kia ora Vivien, congratulations and welcome to the podcast. How do you feel after all that?

Vivien Lei

Kia ora and thank you for inviting me, Terry. It’s great to be here.

Yes, the competition was an amazing experience. You know, we don’t normally have many opportunities to really think about kinds of policy and different things that we could achieve in the future. So, this was a great opportunity for someone young to kind of test the waters, think creatively. And yes, it’s been great to have the support of everyone so far.

Vivien (centre) with the other finalists and members of the Tax Policy Charity judging panel and Deborah Russell MP Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Revenue

Terry Baucher

How did you land on this idea of weighted impact? What was the genesis of the idea behind that?

VL

The competition had three themes and I was immediately drawn to the environment one. I think a lot about the world that we will be leaving for our future generations, because realistically our current trajectory is not sustainable.

I think my non-tax experience has been a key inspiration. Before I started in tax, I was an entrepreneur. I spent six years building and growing early-stage start-ups and social enterprises from scratch, and I assisted with some researchers at the University of Auckland as well, looking at social enterprise ecosystems and impact measurement.

And the other part of my background is I’m also currently Finance Leader of the charitable Fisher Paykel Healthcare Foundation. So, I’m really privileged to have insight into the impact that the board and my foundation lead, interact with, and fund.

Through all of this, I’ve learnt so much from people and the social impact and not for profit sectors, and this experience really underscored for me how important it is to measure impact. So, you can check that you’re having the intended effects and articulate how what you’re doing links to the outcomes you’re aiming to achieve.

And I think others are realising this too. That’s why we’re seeing all these environmental reporting and evolving accounting standards. And I had in my mind that there’s an opportunity here for tax to proactively adapt alongside them and not fall behind.

But if we want to do something about our environment, you really need bold actions and innovation. And I think New Zealand prides itself on innovation and there are some amazing minds out there who could help us tackle this massive issue. My thinking has never been about a sin tax. It’s all about how we can make sure the full costs of people’s activities are clear and then incentivise a significant change in behaviours and norms towards positive environmental outcomes. So that’s kind of how my thinking landed on the impact weighting.

TB

It’s fantastic and fascinating to hear about your background before you got into tax, unlike some poor sad nerd like me who went from university into a tax career. But to me, as we both know, tax has an interesting behavioural impact on that. Your paper points out we have the sixth highest emissions per person in the world and there’s just a little detail about negative environmental impacts like the Rena grounding. It cost the government $46 million, but we only ever got $27 million back from the ship owners and insurers.

So looking at it with an impact approach is a very neat way of doing so. I particularly like the point you picked up that if we can’t buy enough emissions offsets because everyone’s going to be doing that as well. It does come down to some hard decisions about how we measure it, manage it and reduce it is how I’d put it.

In here you said the approach you’ve taken is there are certain businesses that have a negative environmental impact, and they will obviously want to take steps to reduce that negative impact. And the way you phrase it, they get a credit, as I understand it, a credit for doing something positive. Negative impacts are obviously emissions. What would be some examples of positive impacts?

VL

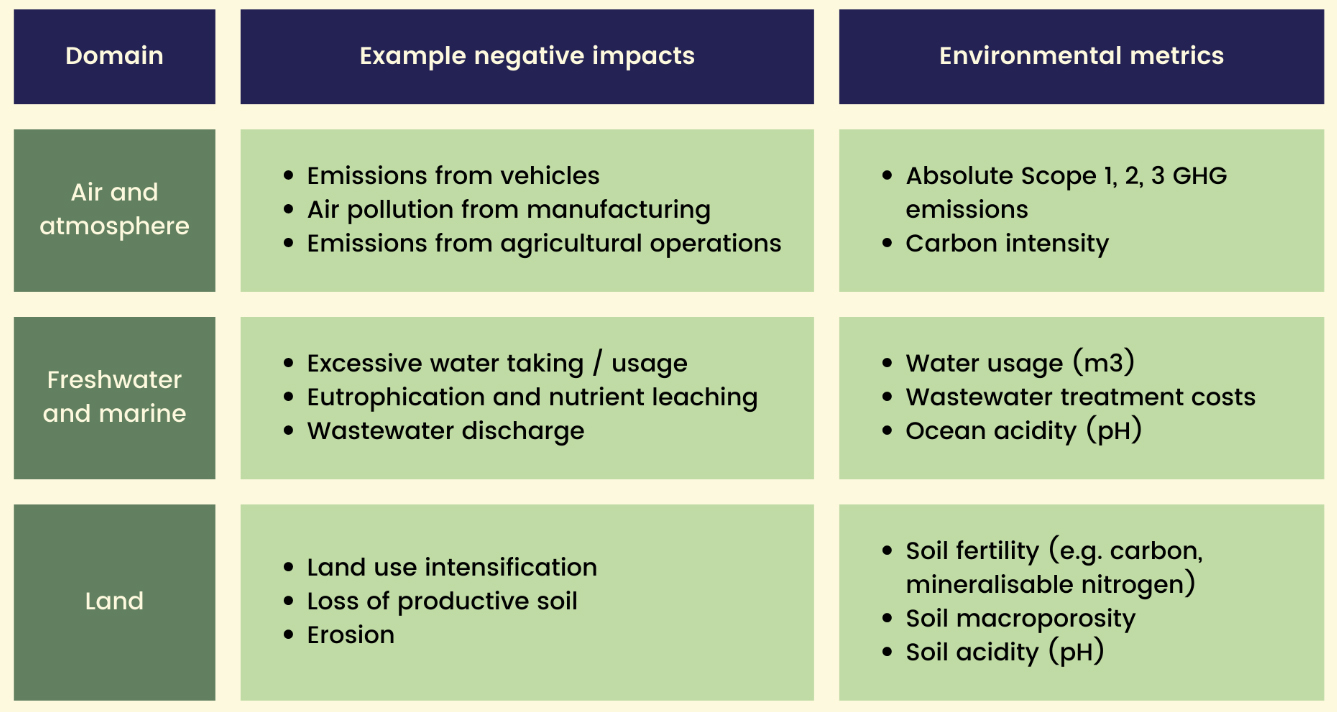

How it functions is organisations continue to be taxed at their standard tax rate, but then they’ll have a permanent adjustment in their statement of taxable income. And that net adjustment will take into account both the negative and the positive impact. What I suggest in my proposal is that we focus on three environmental impact domains, because there are a lot of different types of impacts.

And some of them it’s quite difficult for an individual actor I guess, to measure what their own impact is. So, what I suggested was air, for example, that’s kind of where the emissions is. But there would be other negative impacts now, other domains such as around freshwater, marine and land as well. So that’s kind of a negative impact side.

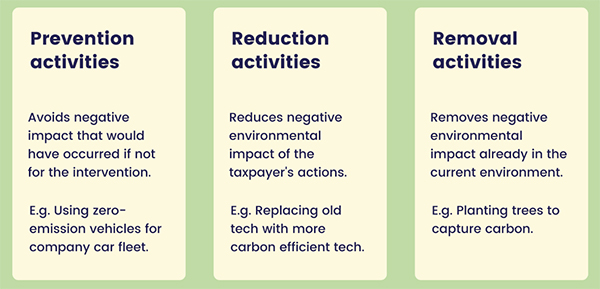

To answer your question on the positive impact. The way my framework sees it is there are broadly three types of activities that would be seen as having a positive impact, and those are namely prevention, reduction and removal activities. The names are probably quite self-explanatory, but you have activities that avoid negative impacts in the first place.

For example, if you just use EVs for your company fleet, then you have avoided having that kind of negative impact. You’ve got ones that reduce environmental impacts, having processes that are more carbon efficient, for example, and then removal as well.

For example, planting trees, or directly capturing emissions and storing them in geological reservoirs. So these are the three types of activities that I see would be seen as valid effectively for having a positive environmental impact.

TB

That’s fantastic. And so, as you said, EVs are a classic example. You have an electric fleet, therefore no emissions, but equally switching away to more efficient ones. You went from ordinary car fleet to hybrids. You’ve also got a positive impact there. Further down the chain, you have some pretty old clunkers you’ve been running around on, and you replace them with newer ones. So they’re even more efficient. So again, each one of those has a positive impact. They’re all a slightly different way, one’s a gold-plated option. The other one’s less gold plated, but quite a realistic option.

Car fleets are getting more and more efficient. Something I know the UK and Ireland do is that they measure FBT on emissions. So obviously, electric fleet, no emissions. If you have a more efficient fleet, fewer emissions, lower FBT. It’s fascinating.

In your proposal, you pick up existing ideas about how to measure impact such as the Australasian Environmental Product Declarations. Would you explain a little bit more about how those work.

VL

Yes. From my experience, both on the academic side, but also when I was running my own ventures, measuring your impact is really not straightforward. It’s an evolving kind of industry at the moment. I would say there’s no universally agreed methodology, but I think this might change because we are seeing the accounting standards start to develop in that area. From my point of view, I don’t want to reinvent the wheel. There are multiple recognised impact measurement methodologies and as long as you’re taking some sort of reasonable approach to measuring impact, I think that’s valid.

In my proposal, one of the frameworks I referenced was the environmental product declaration, and that’s quite good. That’s basically a third party that comes and verifies the lifecycle environmental impact of a product. And there are other kinds of frameworks as well.

So many large corporates will do their own sustainability disclosures. Some of them will have carbon accounting, for example, and then have those disclosures audited by a specific kind of carbon audit firm. And there are other voluntary standards as well. One that we talk about here at my current role at Fisher Paykel Healthcare is the GRI, which is a voluntary kind of global standard. But again, all these show that lots of organisations are thinking about “how do I report to my stakeholders the amount of my emissions or the amount of landfill waste we divert?” these are the kind of frameworks and existing measurements that impact weighted taxation, which leverage effectively.

TB

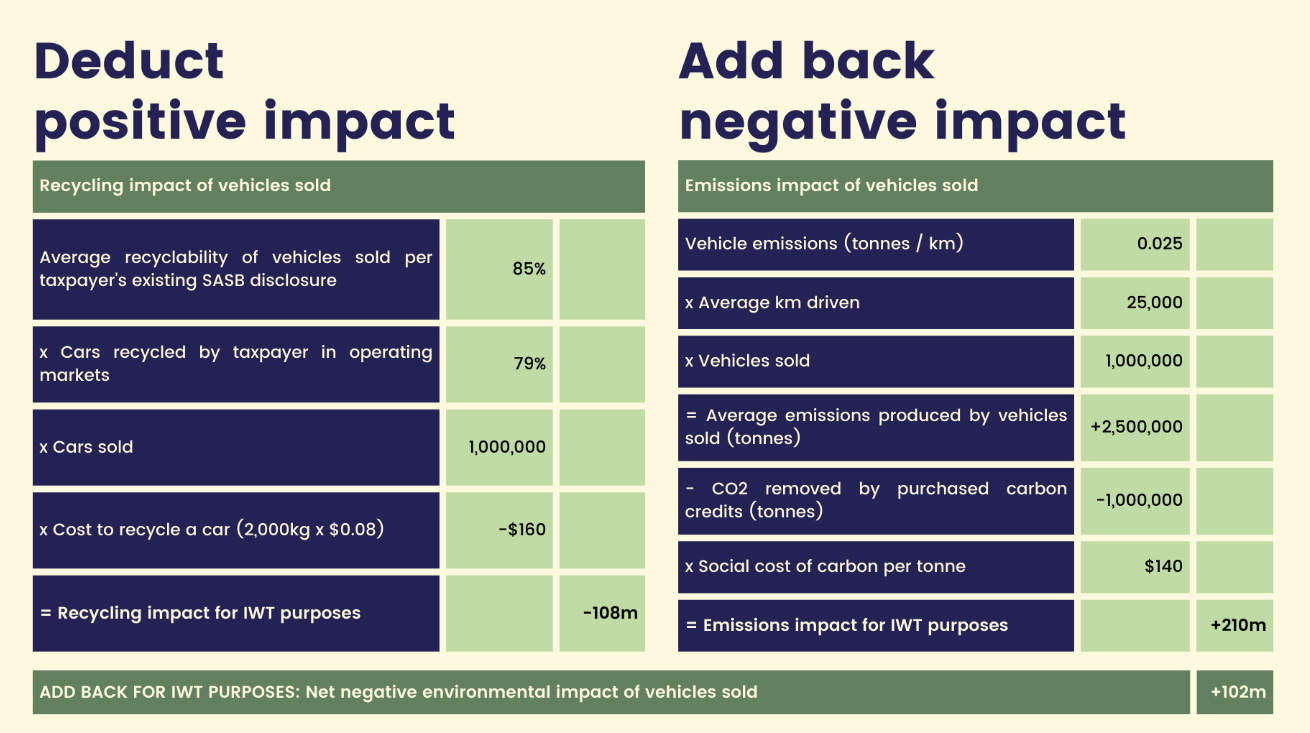

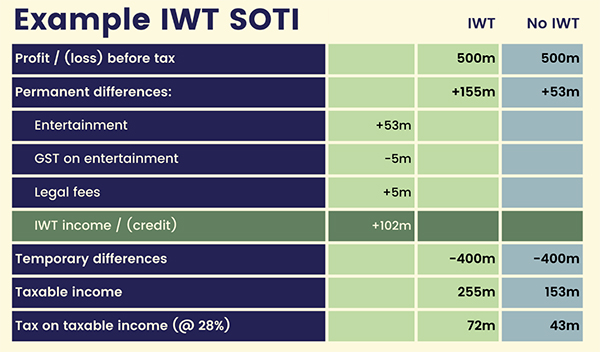

Working through an example, you’ve got your statement of taxable income. So, you start with your profit or loss before tax, and you would make your standard tax adjustments? Then you make the impact weighted adjustment which is basically an add-back or a deduction and it’s a permanent difference, isn’t it? There’s no timing around this. I think that’s a strength, actually, because if there was a timing difference, you’d see manipulation straightaway.

VL

Yes, and it gets complicated quite fast. Yes, just one off. I see it as permanently increasing for most people, their tax payable, eventually in the long term, as people do more and more positive impacts activities. Then it might turn into a deduction effectively.

TB

You’ve prepared an example in here. We’ve got a profit before tax, $500 million, add back permanent differences which would be entertainment $53 million, the GST on entertainment – people often forget that by the way, there’s a whole other podcast I could also do on that. Non-deductible legal fees and then the IWT, the impact weighted Income or credit, which in this case is $102 million.

And then you have the temporary timing differences of $400 million. The net taxable income is $255 million, which the tax on that at 28%, is $72 million. And the difference is effectively without the impact weighted taxation, the taxable income would have been $153 million.

So the impact here for this particular company is an extra $102 million of income at 28%, which today is just over $28 million. Which is, I’d say, a very positive incentive for them to take steps.

A quick question in terms of what happens with the revenue that’s raised there. How do you see that being deployed? As hypothecated or just into the general pool? Over time it would hopefully sink to nothing.

VL

I think that’s right. I didn’t have a firm view on this, to be honest. I see potential either way and I think it’s probably more flexible for the government for it to go into a general pool, because there’s opportunities here. You could either, for example, take it to environmental R&D kind of initiatives, or you could take it to the cleanup kind of budget as well.

I don’t really have a view on this. I think for me, we have a relatively low environmental tax take in New Zealand. And as you mentioned before, these negative environmental impacts are effectively being subsidised by us. The Government is paying for it. We need to reprice these activities effectively and this increased tax take just reflects effectively the cost of the activity that these organisations are undertaking. And how that money then gets distributed just depends on what the appetite is really. But long term you’re right, it should go down and part of that will probably involve quite a bit of investment and innovation to do more positive impact activities. We probably don’t even know what they look like right now but could make a significant difference in the future.

TB

Yes, I totally agree. Your paper, by the way, has some nice little anecdotes. I mentioned the one about the Rena, but here you’re talking about American Airlines, for example. That if it actually had to account for its environmental costs, they would be US$4.8 billion. And airlines are notoriously non-profitable anyway, so that would be the end of that.

And the other thing is emissions prices in New Zealand for our transport emissions would need to be nearly three times the current price to meet our agreements. So what you’re saying is that new taxes are never popular, but we’re not actually pricing the costs of what we do anyway and we should do. Once you do that, it’s interesting to see what incentives come out of that. Am I paraphrasing that correctly?

VL

Yes, that’s absolutely right. And I think part of it is the environmental costs are clear to see at the moment as well. It’s very difficult and that’s why this measurement piece is so key. But I think if an organisation isn’t fully paying those environmental costs, they’re not realising the full cost of their activities.

There’s less of a disincentive for them to stop doing activities with the negative impact. And there’s flow on effects as well. All the stakeholders of the organisation like customers, for example, aren’t getting a clear picture either of what the cost of, let’s say this product is.

So, I think that’s really the thinking around this. “Let’s have a clear picture of what the cost of that activity is.” And you’re right, this does add an incentive to think is there something I could be doing differently to have a positive impact, rather than continuously having negative environmental externalities?

TB

We’re starting to see that. What was it last week – the American court wanting to suspend the import of fish caught from the Maui catchment area. It’s something of a concern I have, because although we are much more than an agricultural economy, food exports are tied to our green image. And so, courts taking action like that is potentially quite alarming for food producers and others.

Obviously you’d want to try and mitigate that possibility. And as you say, the current approach of certain industries buying emission offsets just isn’t driving enough change. I think what you’re saying here, to repeat a point, is that you’re building on existing ideas. This is nothing particularly new. As you said, there is already environmental impact standards. So, it wouldn’t be one that every company could come up with.

I imagine for example, as part of the reporting, you’d tell Inland Revenue, these are the environmental impact standards we have adopted, and so long as Inland Revenue say, well, those are approved, that’s fine. That would be how it would work, I imagine?

VL

Yes, absolutely. I think it’s all about not adding more compliance if possible. So, if there are already methods where organisations are measuring impact or reporting on it within their financial statements then those should be used. So there are various New Zealand organisations doing integrated reporting and we hear a bit about impact weighted accounting.

Last year as well New Zealand became the first country to require certain financial organisations to make climate related disclosures and I think we’ll see the first of those in 2024. I think off the back of all these we are seeing people doing this reporting anyway. And that’s about how can we link the tax payable to that reporting so that organisations are not just merely disclosing what’s happening but actually have some skin in the game to proactively take action about the impact they’re having so far and how to improve it.

I think using existing standards helps with that, and in the future, we saw in New Zealand for example, that the financial organisations have a set standard now and I think probably over the next few years we will see those standards expand for other organisations and industries. And as they do that, there is an opportunity here for tax to really adapt alongside them and not just wait for the full standards to be implemented before we think about how does tax fit in with this? I think as the accounting standards go on this journey of understanding what this will look like, so too should tax.

TB

Yes, tax change is quite interesting. Take the shape of the New Zealand tax system. The other day I looked at 1949 to see what’s in our tax take then. There was even an “Amusement tax”, for example. And then compare that with our system now, and you can see how it evolves over time which is what should be happening. Tax can in some ways lead that change we desire.

So, I’m looking at this proposal and thinking, “Oh my God, I’m a small one-man business. How is this is going to apply to me?” But you’re saying initially it would be larger organisations to begin with. What would be the break point, the cutoff point, so to speak? And would that be a sinking lid, as more and more people came into it as the system bedded in.

VL

Yes. I think the initial scope for implementation is voluntary at the start, especially until accounting standards mandate disclosures. That will give people time to work through how this regime would work. And yes, I see large organisations first, consistent with an IFRS accounting definition. https://www.xrb.govt.nz/standards/accounting-standards/

And the reason for that was large organisations are probably some of the biggest contributors to the environmental impacts just due to their scale and size. They’re most likely to be doing some sort of voluntary measurement or reporting already and their actions will have a significant positive impact because of their scale and size. So that’s why I picked large organisations first.

I do think that we have to balance the complexity of measuring environmental impact versus the likely costs that the government would have to subsidise without impact weighted taxation. So, for a smaller organisation, I guess there could be a lot of complexity, especially in these early stages when we’re all trying to figure out how this works. That’s quite difficult.

I do think though, that the impact measurement capability will improve and become more commonplace long term. It would be appropriate to widen the scope in the future. And there is a lot of support out there for all kinds of small and medium sized organisations as well.

I know Sustainable Business Network has been coming out with toolkits aimed at SMEs to help them with impact measurement and reporting. So, as we evolve this and see how the first kind of adopters respond to this regime, and in many years to come, we will be ready for small and medium sized organisations to participate in Impact Weighted Taxation.

And for some of them this could be a huge opportunity as they are realising that customers are interested, and prefer positive environmental impacts, and that could be quite helpful to their business from a customer point of view. And if it also helps their business from a tax point of view, that’s very nice as well that there’s synergies there. I think that might be what it will look like long term.

TB

I would say that for some they might find we’ve got a competitive advantage here because we are a low carbon emitter, we’re just a low carbon industry or business, and we’ll jump in on this. By the way what is the definition of “large”?

VL

The amounts were updated earlier this year. It’s either total assets in excess of $66 million or turnover exceeding $33 million.

TB

So similar to the company’s office reporting standards. That’s still a reasonably sized proportion of businesses in New Zealand. Several thousand businesses could be within that.

VL

Absolutely. Much like implementing other tax regimes, you’d first trial it with a few of them. For example, for the R&D tax credit regime Fisher Paykel Healthcare was one of the first to trial that. So that’s probably the key in the initial implementation, voluntary, choosing a select group if needed before you have all large organisations participate. For these kinds of things, it’s key to try it out and see how the details work. I’ve just started some of the thinking here, but I’m sure there will be many other things to work through as well because these kinds of regimes are not simple.

TB

But they are necessary, the key point you make is we move to a circular economy. You estimate moving to a circular economy within Auckland alone would be worth $8 billion by 2030, which isn’t that far off. These decades roll round very quickly. This is coming towards us much more quickly. Steps and initiatives like this are what we need. We’ve got to try everything.

VL

That’s right. The circular economy is probably a concept we’ve talked about quite a lot recently because everyone’s realising, we need to change our practises hugely. And the way we’re going to do that is to design all the waste out.

We’ve got to make sure everything can be reused, recycled, reprocessed for as long as they can be before they reach the end of their life. Technology can really help us with this as well in terms of figuring out what happens to all these materials. There is an opportunity here for tax to incentivise that as well, so that we effectively accelerate our actions towards that.

TB

There’s no doubt, as we both know, tax has a very interesting behavioural impact on people. And as I said, I think for smaller businesses that may have opportunities where they could essentially be in credit, they will take it up, and other businesses that realise we have a problem here will take action appropriately.

And to borrow a phrase I’ve heard about the All Blacks, sometimes we think we need a big bang. We need to just find something that captures emissions and that’s the end of it. But actually, a lot of 1% adjustments will get us there. And I definitely think your proposal is one of those 1% adjustments.

VL

Absolutely. It’s about incentivising all the small actions, every little bit counts. That just reflects the reality that every little thing we’re doing will help the environment and that is ultimately going to benefit our economy.

You reference the clean, green image that we so value here at Aotearoa. And a lot of our industries, agriculture, fisheries, these are all very closely linked to our environment. So being able to incentivise things towards us, this is going to help our long-term economy as well.

TB

Well, that seems a great point to leave it there. Thank you so much Vivien, for coming on. And congratulations again on what is a fascinating paper, I’m looking forward to seeing more of this and dealing with it myself.

That’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time ka pai te wiki – have a great week.