- Inland Revenue gets tough with parents.

President Trump was inaugurated for his second term last week, and he swiftly set about implementing his agenda. In his inauguration speech he remarked “America will no longer be beholden to foreign organisations for our national tax policy, which punishes American businesses.” This prompted me to ask on LinkedIn what the potential implications could be for the OECD Two Pillar agreement?

Repudiating the OECD Two-Pillar proposal

Well, President Trump didn’t wait long to take further action. In fact, pretty much almost immediately he issued a Whitehouse Executive Order railing against the “Global Tax Deal” which “limits our Nation’s ability to enact tax policies that serve the interests of American businesses and workers.” Instead, the Executive Order “recaptures our Nation’s sovereignty and economic competitiveness by clarifying that the Global Tax Deal has no force or effect in the United States.”

The Executive Order goes on to direct the Secretary of the Treasury (the equivalent of our Finance Ministerand the Permanent Representative of the United States to the OECD) to

“…notify the OECD that any commitments made by the prior administration on behalf of the United States with respect to the Global Tax Deal have no force or effect within the United States absent an act by Congress adopting the relevant provisions of the Global Tax Deal.”

So “Shots fired” would be the quick response to that. But it’s Section Two of the memorandum which caught my eye when I looked at it. The Order doesn’t have the technical and legal language you might expect, but it’s written with very much the voice of Trump.

Getting your retaliation in first

Section Two of the Order discusses options for protection from discriminatory and extraterritorial tax measures. It directs the Secretary of Treasury in consultation with the United States Trade Representative, to

“…investigate whether any foreign countries are not in compliance with any tax treaty with the United States or have any tax rules in place, or are likely to put tax rules in place, that are extraterritorial or disproportionately affect American companies, and develop and present to the President, through the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy, a list of options for protective measures or other actions that the United States should adopt or take in response to such non-compliance or tax rules.”

Now that is something that I don’t think many people have yet noted. Basically, it’s a pre-emptive strike at other governments responding to what appears like an almost certain collapse of the OECD’s Two Pillar solution by adopting digital services taxes (DSTs). We’ve introduced (but not yet enacted) that legislation. Several countries such as Canada and France do have DSTs in place as a backstop in case the OECD’s Two Pillar solution fell over.

So now we’re in very interesting times. And the issue is that the large tech companies in particular are the target of the Two Pillar solution. Mark Zuckerberg, the head of Meta, together with the head of Google, as well as Elon Musk, owner of the site formerly known as Twitter, all had prime seats at President Trump’s inauguration. Musk in addition, heavily financed President Trump’s campaign. All now have the President’s ear which will maybe enable retaliatory actions by the US against attempts by other governments to say, ‘Well, wait a minute, without the Two Pillar deal we’re losing revenue ourselves here.” The collapse of the Two Pillar solution could provoke the 2020’s tax equivalent of the notorious Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which is often credited with triggering the Great Depression of the 1930s.

What could be the impact in New Zealand?

We are a small player, but from our perspective it’s quite relevant how we tackle the taxation of the tech companies. According to Google and Facebook’s financial statements for the December 2023 year, the two companies probably captured about $1.1 billion in advertising all of which was sent offshore. However, the reported taxable income for those two companies for the 2023 year was just under $28 million before tax.

I’m bringing this up because this week NZME announced that it was cutting its newsroom staff by 40, and the financial woes of the media are well documented. Media is struggling as its advertising revenue has essentially collapsed because large chunks of it are now being paid offshore.

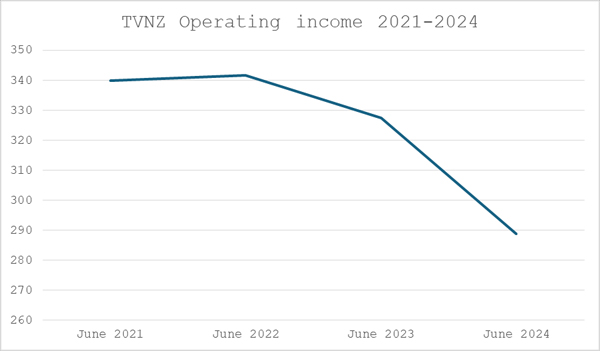

If you want to put it in some context of just how bad the problems are for our media, TVNZ’s pretax 10 years ago for the year to June 2015 was $333.9 million.

You’d expect with inflation those numbers would have risen. In fact, for the last three years, TVNZ’s revenue has plateaued at $339.9 million for 2021, $341.7 million for 2022 and $327.6 million for 2023 before falling by $39 million to just under $289 million for the year to June 2024.

The media is in desperate financial states and that has the knock on effect for the Government, because sooner or later it will be called on for some sort of financial support. An option the Government might consider is whether a levy of some sort could be directed at advertising, which is paid offshore.

Sooner or later a New Zealand government will be put in the position where it may have to make an uncomfortable call. Meanwhile, we have the United States making it very clear that it is not going to accept the Two Pillar solution – and would take retaliatory action if it felt its companies’ business interests were threatened by a DST or other levy. It’s not a great scenario and makes for a pretty rocky start to the year.

Raising taxes on the quiet?

Moving on, an interesting story came out over the holiday break in relation to the International Visitor Levy (IVL). Now this was quite controversially increased from $35 per head to $100 from 1st October last year. This move is expected to raise $149 million. The increase to $100 was way above what the tourism industry wanted or what ministry officials recommended. The IVL must be spent on tourism and conservation, essentially, it’s what we term hypothecated – ring fenced for those particular areas.

It turns out that there’s some digging been done by Derek Cheng at The New Zealand Herald, who found out under the Official Information Act that there was quite a bit of ministerial wrangling over how it might be possible to divert or repurpose the IVL income to improve the Government’s overall finances.

Essentially, the dramatic increase in the IVL enabled central government funding which would have gone to the Department of Conservation to be frozen. According to the Herald report this move gave the Government approximately $307 million of ‘fiscal headroom’.

Now there’s nothing wrong with this move although stakeholders in the sector are unhappy with the result. Apparently, the Minister of Finance Nicola Willis wanted to have the IVL funds become part of the Government’s Consolidated Fund where it could be spent as she directed. That was rejected as it would require a change of law.

I think this attempt indicates we’re going to see more of this tactic from the Government. Nicola Willis made a passing comment at a briefing that she’d like to make more use of fees and levies to raise revenue. Looking ahead, the budget in May will give us a really good indicator of how increased fees and levies might be used to basically shore up the Government’s books.

It’s a sleight of hand way of finding additional revenue without explicitly raising taxes directly. Fee increases such as those for the IVL means although the rates of personal income tax and GST remain the same, the Government is managing to extract additional revenue.

So, watch this space. Governments all around the world are trying to do this. In some cases, it’s appropriate, it’s a bit like user pays. But in other cases, you wonder if it’s just a little bit too much financial wizardry for the sake of it.

Inland Revenue targeting collection of tax debt

Unsurprisingly Inland Revenue is continuing its actions we saw last year of increased activity in collecting debt. Stories have emerged since the start of this year relating to its pursuing families for overpaid Working for Families credits.

RNZ ran a story on 20th January about a parent who had incorrectly recorded her relationship status for Working for Families only for Inland Revenue to advise her she now owes $47,000. This was the third such report this year with the other two stories involving tax bills of $9,000 and $24,000 respectively. Inland Revenue’s response is that these are the rules, and it has to carry on and collect the overpaid credits. However, I am aware that there have been issues with parents registering new-born children through the Department of Internal Affairs website resulting in overpayments.

Don’t look at me, I’m only the Minister

When RNZ asked the Minister of Revenue Simon Watts for comment, he responded it was an operational matter for Inland Revenue.

“I’m advised that this issue affects a small number of taxpayers who have received an overpayment due to not providing IRD with the most recent information on their circumstances.”

To be fair to Inland Revenue, as Susan St John, an economist and Child Poverty Action Group member said, the problems were not with Inland Revenue’s application of Working for Families, but with the system itself.

This touches on a point I’ve made repeatedly in the past. Working for Families tax credits begin to be clawed back (abated) where family income is at $42,700 per annum. Above that threshold, Working for Families is abated at a rate of 27 cents for every dollar earned above that threshold. Now that threshold has not been changed since June 2018, and I had a somewhat testy exchange with the Minister of Finance at the Budget Lockup in 2024 over the fact the threshold was left unchanged.

Who suffers the highest Effective Marginal Tax Rates? It’s not who you might think

As a consequence, families on relatively low incomes face very high effective marginal tax rates. Coincidentally this week Treasury released a paper The Cost of Working More: Understanding Effective Marginal Tax Rates in New Zealand’s Tax and Transfer Systems which analyses the impact of effective marginal tax rates on work incentives. The paper examines what happens to a person’s effective marginal tax rate, when their income rises resulting in higher tax rates or the abatement of benefits such as Working for Families.

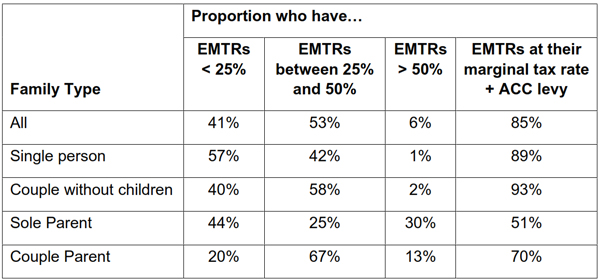

The paper notes that for most persons their effective marginal tax rate (EMTR) is equal to their top tax rate. For example, someone earning over $180,000, with no other benefits, their EMTR would be 39%. In other words, for every dollar they earn above that threshold it is taxed at 39%. Overall, most New Zealanders’ EMTRs are below 50%, with only 6% experiencing EMTRs of over 50%.

But the distribution of high EMTR varies significantly across different family types. Families without children generally experience low EMTRs.

Therefore, they have higher work incentives because they are less likely to be receiving government support payments that would be reduced by increases to income. Around 90% of such families have EMTRs equal to their marginal tax rate.

“The Iron Triangle”

The paper notes the issue of what it calls “the Iron Triangle”. This is the inherent trade-off between three competing objectives – providing adequate income support, maintaining reasonable government costs and preserving work incentives. Whatever you do, you’re never going to hit the sweet spot on any of that. It’s therefore a question of continual adjustment.

The paper is very interesting as it breaks down the various family types, the composition of their income and the benefits they receive. People might be receiving Best Start, Working for Families, Accommodation Supplement, all of which are subject to some form of abatement and at differing rates. The paper then analyses what happens when people start earning additional income and the numbers are really quite astonishing. The paper concludes parents are the group that most likely face financial disincentives to work because of the impact of high effective marginal tax rates.

Where it gets really problematical as these abatements start kicking in is for families with children. 13% of couple parent families have EMTRs greater than 50%. 30% of all single parent families have effective marginal tax rates greater than 50%. And there are a number of families with children that have EMTRs higher than 100%. The stats don’t reveal just how many people that might be affecting, but it’s certainly 20,000 to 50,000 it would seem. Which is a substantial number of people.

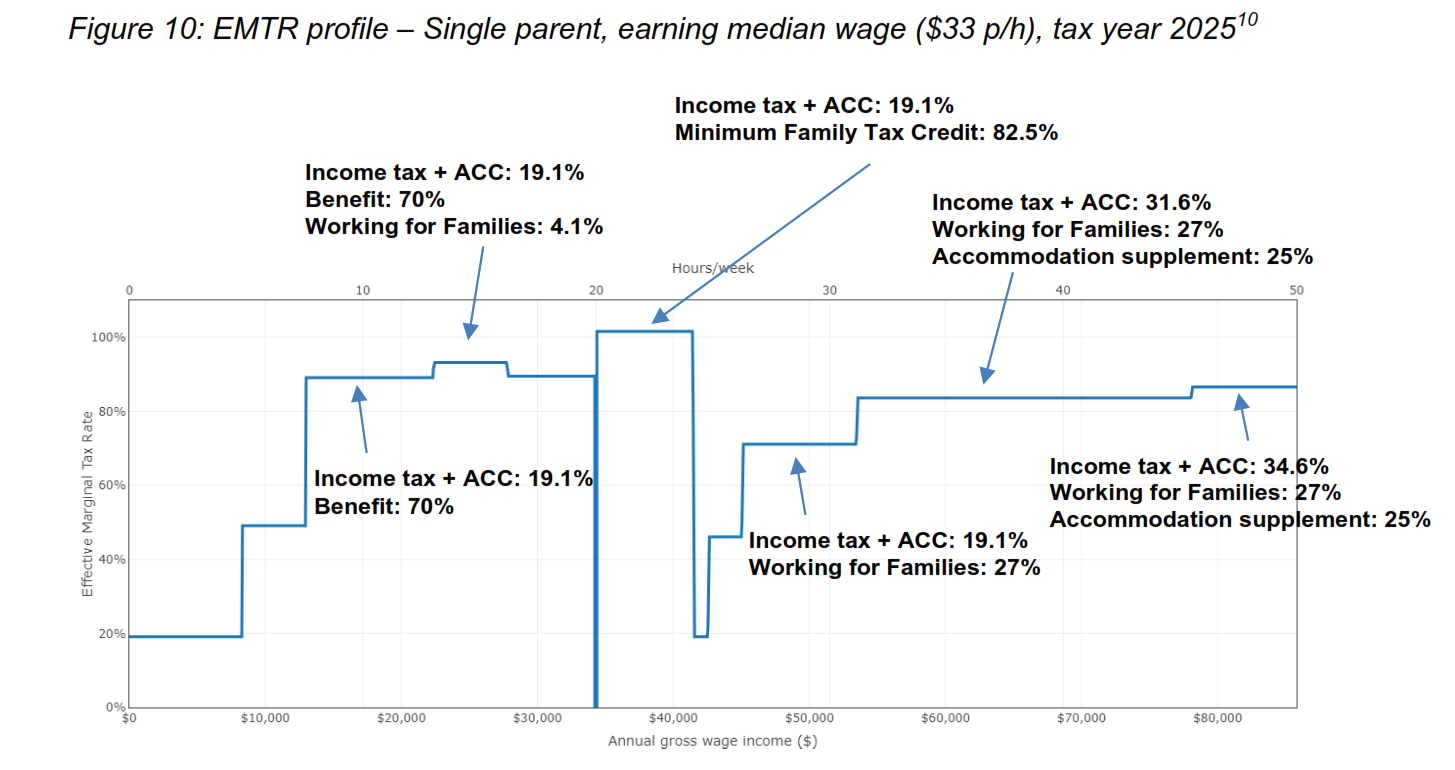

Figure 10 in the paper shows the EMTR profile for a sole parent family earning the media wage of $33 per hour. As the paper notes regardless of weekly working hours the parent faces high EMTRs almost consistently:

1. When working between 8 to 20 hours per week, they keep only around 10 cents of each additional dollar earned due to income tax and reductions in benefits and Working for Families tax credits.

2. When working between 20 to 24 hours, they keep none of the additional dollar earned due to reductions in the Minimum Family Tax Credit, income tax, and the ACC levy. In this case, they actually lose nearly 2 cents by earning an extra dollar.

3. When working between 26 to 31 hours, they keep slightly less than 30 cents of each additional dollar earned due to income tax and reductions in Working for Families tax credits and Accommodation Supplement.

4. When working between 31 hours and full-time11, they keep less than 20 cents of each additional dollar earned due to a higher income tax rate and reductions in Working for Families tax credits and Accommodation Supplement.

A long-standing issue no-one seems to want to fix

Compounding the matter, the paper notes that parents may be limited by childcare costs when choosing to increase their work, as there are fewer adults within the household supervising care for children. Overall it concludes:

“While the system generally preserves work incentives for most of the population, certain family types, particularly single parents, face significant financial disincentives to increasing work hours. This suggests that future policy development may need to focus on whether current abatement thresholds and rates are optimally placed.”

My response is that current abatement thresholds and rates are not “optimally placed”’ which was something the Welfare Expert Advisory Group was saying back in 2019. As I previously mentioned, the $42,700 abatement threshold for Working for Families (which is the limit of family income, not individual income) has not been increased since 2018, so there’s a real issue here. The Minister of Finance, who is now the Minister for Economic Growth, is keen on getting people into productive work as part of that. But people are not going to take up additional work if they realise that between the abatements and the additional childcare costs they’re going backwards.

It’s a long running issue and it will be very interesting to see what response the government makes to that. As always, we’ll bring you developments.

On that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher, and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening. And please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.