20 May, 2019 | Tax News

Tax is full of unintended consequences and one such instance is probably critical to Jenée Tibshraeny’s exposé of the problems many bodies corporate of apartment blocks now face.

The story begins in January 2010 when the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group (the VUW TWG) released its report. The VUW TWG’s key recommendation was for the personal, trust and company income tax rates to be aligned as far as possible. This would involve a reduction in the top personal income tax rate from 38% to 33%. The VUW TWG also commented on the need for the company income tax rate to remain competitive.

The VUW TWG also recommended broadening the tax base “to address some of the existing biases in the tax system and to improve its efficiency and sustainability.” It then noted that base-broadening would be “required if there are to be reductions in corporate and personal tax rates while maintaining tax revenue levels.” The VUW TWG suggested that one such base-broadening measure could be an increase in the rate of GST from 12.5% to 15%. Another measure could be “Removing tax depreciation on buildings (or certain categories of buildings) if empirical evidence shows that they do not depreciate in value.”

The evidence presented to the VUW TWG indicated commercial and industrial properties did in fact depreciate in value. However, this didn’t appear to be the case for residential properties.

Accordingly, the initial costings for the 2010 Budget only proposed the removal of depreciation on residential properties. This would raise approximately $340 million in its first year which would help pay for the proposed income tax cuts. Once it was decided to reduce the company tax rate from 30% to 28% (a measure expected to cost $410 million in its first year), the decision was also taken to remove depreciation from all buildings. This raised a further $345 million towards the personal income and company tax cuts.

The National Government duly adopted the VUW TWG’s tax rate alignment proposals, announcing these in its 2010 Budget released on 20th May. With effect from 1 October 2010 personal income tax rates and thresholds would be adjusted and the present top personal rate of 33% introduced. The rate of GST would increase to 15% with effect from the same date and tax depreciation on all buildings would be removed with effect from the start of the 2011-12 income year (1 April 2011 for most taxpayers).

Then the Canterbury Earthquakes happened.

By 1 April 2011 it was quite apparent that owners of commercial and residential investment properties in Canterbury faced significant repair and/or rebuilding costs. Furthermore, all commercial property owners throughout New Zealand would also need to carry out seismic strengthening at a cost initially estimated to be almost $1.4 billion.

Owners of investment properties also had a big tax problem – was the cost of repair and seismic strengthening work tax deductible? Prior to 1 April 2011 if expenditure wasn’t deductible it could at least be depreciated. Repairs were probably deductible but investors rebuilding properties could no longer claim a depreciation deduction unless they could demonstrate the building’s life would be under 50 years. As for seismic strengthening the tax treatment was unclear – were they a repair and therefore deductible or an improvement and non-deductible?

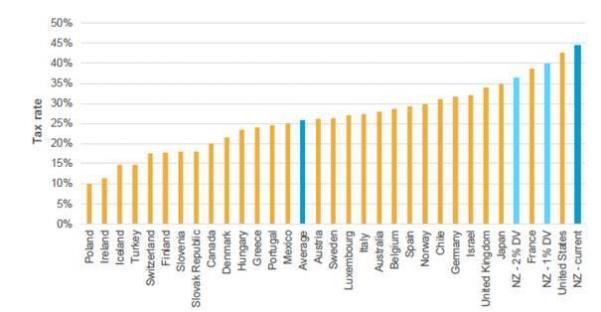

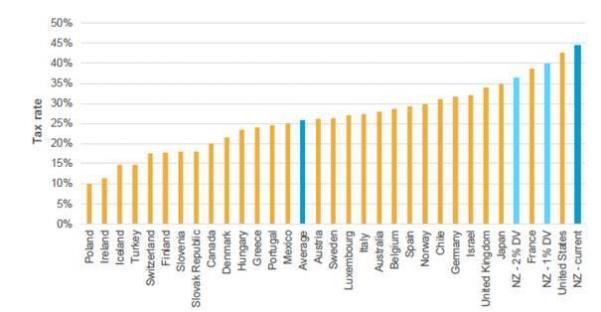

This unsatisfactory state of affairs has continued since then. It caught the attention of the latest Tax Working Group (the Cullen TWG). It noted that the withdrawal of depreciation now meant that by 2015 New Zealand had the highest effective tax rate for foreign investment into both manufacturing plants and office buildings among OECD countries.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG estimated the fiscal costs over five years of these various options as between $70 million (seismic strengthening only) and $1.46 billion (industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings).[1] They were, of course, conditional on the availability of additional revenue from the extension of the taxation of capital gains.

As we know, that isn’t happening but fortunately the treatment of seismic strengthening is one of the Cullen TWG’s recommendations which is a high priority for inclusion in Inland Revenue’s tax work policy programme. Frankly, nearly nine years after the Canterbury Earthquakes first hit, this is a well overdue move.

The Cullen TWG interim report in September 2018 also had some commentary on the effects of the reduction of company tax rates in 2010.

“The two most recent reductions in the company rate in New Zealand – in 2008 and 2011 – were not associated with an increase in foreign investment. In fact, the stock of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP trended down slightly in the following years. There was also no increase in the level of foreign investment relative to Australia, whose company rate was unchanged during that period.”[2]

In short, New Zealand didn’t get much return in the form of foreign direct investment for its cuts in the company tax rate.

There is perhaps one final irony at play here: holders of investment properties were among the fiercest critics of the Cullen Tax Working Group’s recommended capital gains tax. Did they win that battle at the cost of the loss of the reintroduction of building depreciation? If so, may that win turn out to be a Pyrrhic victory?

[1] Table 6.1, Chapter 6

[2] Para 21, Chapter 14

This article first published on Interest.co.nz

18 Apr, 2019 | Tax News

So, no Capital Gains Tax to rule them all, not even a wafer-thin mint partial extension of the existing bright-line test to cover all residential investment property/holiday homes. I’m almost certainly not the only one who didn’t see that coming.

The other big surprise for me is the decision to not prioritise any new environmental tax proposals for now. When introducing the TWG’s final report Michael Cullen made much of using the funds from these measures to help farmers transition to a lower-carbon economy. That appears to have fallen by the wayside for the moment.

The Tax Working Group made a dozen recommendations regarding environmental and ecological outcomes. One of these was to develop a framework for taxing “negative environmental externalities” (i.e. pollution).

The TWG report noted that the approximately $5 billion of environmental taxes raised in 2016 represented about 6.2% of tax revenue. According to the OECD, New Zealand ranked 30th of 33 OECD countries for environmental tax revenue as a share of total tax revenue in 2013.

Surprising and a little disappointing

Accordingly, given our dependence on the environment for our agricultural and tourism sectors, it’s surprising and a little disappointing that the TWG’s recommendation for developing a framework is simply rated “Consider for inclusion in the 2019/20 tax policy work programme.” Furthermore, the Government has decided not to advance any new environmental tax proposals other than those within the current tax policy work programme.

The other eleven environmental proposals covered Greenhouse gases, water abstraction and water pollution, solid waste and transport. All are within the current tax policy work programme, but critically the Government has ruled out both resource rentals for water and the introduction of input-based instruments such as a fertiliser tax in this term of Parliament. Unlike CGT these issues are not completely off the table.

Although property owners in particular will be relieved by Wednesday’s decision, there will be far more losers as a result because the TWG’s suggested options for recycling the revenue raised from a CGT through reductions in personal income tax are off the table entirely. This would appear to include any changes to tax rates and thresholds which might come out of any proposals made by the Welfare Expert Advisory Group.

However, given the current tax rates and thresholds have not been adjusted since 2010, the issue of personal income tax reductions is not going away. Today’s decision probably increases the pressure on the Government to make some changes in next month’s Budget.

So which TWG recommendations has the Government marked out as high priority?

The most significant would be introducing measures to counter land-banking and land speculators. The TWG’s final report suggested residential vacant land taxes were best levied by local government. There are few other details so far apart from a direction for the Productivity Commission to include vacant land taxes into its enquiry into local government funding and financing.

The other high-priorities include the tax treatment of seismic strengthening work which frankly should already have been a priority; an interesting proposal from the New Zealand Superannuation Fund to develop a regime encouraging investment into nationally significant infrastructure projects; and a number of technical tax integrity items relating to loss-trading, and better tax collection.

Overall the TWG made 99 recommendations. Eleven have been deemed high priority for progression in the 2019/20 current tax policy work programme. The Government rejected 14 including CGT; another 14 such as the current rate of GST are current tax policy and will remain unchanged; work is already underway on considering 30 recommendations and the remaining 30 should be considered for inclusion in the tax policy work programme in due course. This last group includes business taxation changes aimed at reducing compliance and the TWG’s suggested changes for KiwiSaver. Given the well documented imbalance of tax treatment between residential property and KiwiSaver funds this is particularly disappointing.

‘Not healthy for a democracy for interest groups to wield such influence they can effectively exempt themselves from tax’

Finally, a note on the politics of the decision. I do not believe it is healthy for a democracy for interest groups, whether property owners, business owners or multinationals, to wield such influence that they can effectively exempt themselves from tax.

Over the past 50 years various working groups at regular intervals have reviewed the tax system, considered the merits or otherwise of a capital gains tax and then backed off. In between each review governments of both hues have steadily broadened the scope of taxation.

The Prime Minister may have said no this time, but the pressure for widening the scope of capital taxation still remains whether it’s from widening inequality or the continued tax-favoured status of property investment. We will therefore be re-litigating the issue of capital taxation within 10 years.

This article first appeared on Interest.co.nz

18 Apr, 2019 | Tax News

Perhaps the Tax Working Group was fatally compromised from the outset when the taxation of the family home was excluded from its terms of reference. My view is that too often proponents of a capital gains tax default to arguing the difficulties and are therefore on the back foot from the outset.

Even so, the decision to not expand the taxation of capital gains in any form is extremely surprising, not just to me but probably also even to groups such as the New Zealand Property Investors Federation.

But the question of a CGT was just one of the issues the Tax Working Group (TWG) examined. Its final report contained 99 recommendations across the entire tax system. The government’s response to these recommendations breaks down into five categories:

- rejected and no further work;

- the recommendation is a high priority for the tax policy work programme;

- the recommendation should be considered for the current tax policy work programme;

- the recommendation represents policy work which is already underway; and

- endorsed because the TWG agrees with the present policy settings and the government agrees with the recommendation.

Also dead in the water alongside CGT are 13 other recommendations, including all the TWG’s proposals for using the proceeds of a CGT to reduce personal income tax, a framework for applying any new “corrective taxes” and the development of a clearer articulation of the government’s goals regarding sugar consumption and gambling activity.

Finally, there will be no new environmental tax proposals beyond those already on the tax policy work programme. This also means that this parliamentary term there will be no resource rentals for water or input-based instruments such as a fertiliser tax.

The lack of significant environmental taxation changes is perhaps as big a surprise as the CGT decision. This is not only because it represents a clear rebuff for the Green Party, but also because during the media lock-up at the launch of the TWG’s final report, Sir Michael Cullen made much of recycling environmental taxes to help farmers transition to a lower-emission economy.

Not proceeding with a CGT means the TWG’s suggestions over using the proceeds to reduce income tax particularly for lower income earners will not proceed. This leaves the government with the problem of what to do about income tax thresholds which now have not been adjusted since 2010. Pressure for some movement on these will continue to build up until and beyond next year’s election.

The 11 recommendations that the government considers a high priority for the tax policy work programme are a mix of system integrity issues such as a review of tax loss-trading, better compliance around debt collection, and more politically visible initiatives like seismic strengthening work (which given it’s been more than eight years since the Canterbury earthquakes is something which really should have been resolved by now).

Devising rules for land speculators and land bankers is also a high priority but there’s not much detail at the moment. The TWG suggested that local government should levy residential land taxes on vacant land and the government has told the Productivity Commission to include this issue as part of its inquiry into local government funding and financing. We shall have to wait to see more detail on this initiative.

The TWG made a number of recommendations regarding compliance costs for businesses. All of these have been put into the “consider for inclusion in the tax policy work programme” category. It would have been good to see these be given higher priority, as several measures which increased thresholds such as that for provisional tax would be very helpful for smaller businesses. Instead, the tax policy process means that it could be two, or more likely three, years at the earliest before these recommendations become law.

To be frank, although the TWG’s recommendations around business compliance costs are welcome, they are also on the timid scale. For example, there’s nothing which compares with the proposal in the recent Australian Budget allowing small businesses to instantly write off assets costing less than A$30,000.

All of the TWG’s proposals regarding international taxation are already in the work programme. This means that an Inland Revenue discussion document about a digital services tax will be released in May.

Watching international developments on equalisation, or diverted profits taxes, is part of the current work agenda. It’s interesting to note that Britain’s HM Revenue and Customs has seen its tax take from diverted profits tax rise from £31 million in the 2015-16 tax year to £388 million in 2017-18. HMRC puts part of the increased tax take down to behavioural changes by multinationals following the introduction of the diverted profits tax. Could a diverted profits tax have a similar effect in New Zealand?

The TWG’s recommendations relating to retirement savings such as reducing prescribed investor rates of KiwiSaver funds for those earning below $48,000 have been parked in the “consider for inclusion” pile. And the deferment of this work highlights one of the issues a CGT was intended to address: the imbalance in tax treatment between various asset classes.

With the decision to walk away from a CGT, property investors retain their significant tax advantage over ordinary savers and those investing via KiwiSaver funds. It is this continuing imbalance in treatment plus the wider concern of growing wealth inequality which means that despite her decision today the prime minister has, as Macbeth lamented, “scotch’d the snake not killed it.” We will be re-litigating these issues in another ten years if not sooner.

This article first appeared on The Spinoff

17 Apr, 2019 | Tax News

In case you’ve not heard, the big news this week is the start of the final season of Game of Thrones. Oh yes, we also should hear which of the Tax Working Group’s recommendations the Government proposes to implement.

Judging from media commentary over the past few weeks “Winter is coming” would not inspire as much existential dread as “CGT is coming.” As I noted previously there’s much more to the TWG report than the taxation of capital gains. Just to recap, the group’s principal recommendations also included:

- expanding environmental taxes (an “immediate” priority);

- measures to enhance business productivity including possibly restoring depreciation deductions for buildings;

- the Government should be ready to follow other jurisdictions and introduce a digital services tax on multinationals;

- changes to KiwiSaver;

- possibly exempting the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from taxation;

- increasing the bottom tax threshold;

- more powers for Inland Revenue to address non-compliance and the cash economy;

- establishing a single Crown debt collection agency;

- considering corrective taxes such as a sugar tax; and

- reviewing the current treatment of business income for charities and verifying whether charities are achieving the intended social outcomes.

It’s a long list of recommendations which will potentially affect all taxpayers in some form or other.

But despite all of the above, attention will almost exclusively be focussed on how far the scope of capital gains will be extended.

Although three members of the TWG, Kirk Hope, Joanne Hodge and Robin Oliver do not support a broad-based capital gains tax across all assets, the entire group did back extending the taxation of residential rental investment property. As justification the report noted[1]

“the current approach to taxing rental income does not come close to taxing the expected total income from residential rental investment properties when capital gains are included.”

At the very least we should therefore expect residential investment property and second or holiday homes to be taxable on disposal. This could include lifestyle blocks but not farms (although farmers should probably expect to see the TWG’s environmental recommendations adopted).

According to the TWG’s final report the initial impact of taxing residential rental investment and second homes would be an additional $50 million of tax in the first year. However, this is expected to increase steadily reaching over $2.5 billion by the tenth year.

Apparently lost amidst the noise from opponents of an expanded CGT, is the Government’s direction to the TWG after the publication of its interim report to develop revenue-neutral packages of tax reform. The TWG’s final report suggested four alternative packages[2] costing between $7.3 and $8.7 billion over a five-year period. (Intriguingly, none of these packages included exempting the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from tax, a measure which alone would slash more than one billion dollars from the tax take). A limited expansion of CGT will mean any such packages will probably need to be scaled back.

Next month’s Budget will be the first prepared using Treasury’s new Living Standards Framework. The Government may therefore want to hold back announcing specific details regarding implementing some of the TWG’s recommendations until then.

In reality, the intention to have any relevant legislation in place to take effect from 1 April 2021 does favour a limited expansion of CGT at this point. With the general election due next year, probably in September, a bill incorporating the legislation for an expanded CGT would need to be ready by November this year. This would allow just enough time for the bill to go through Parliament enabling the Finance and Expenditure Select Committee (FEC) to hear submissions before being passed some time in June/July next year prior to the general election.

A potential difficulty for the Government is that the FEC is currently tied up considering submissions on the legislation relating to proposed ring-fencing rules. These rules were intended to be operative as of the start of the 2019/20 income year, which for some taxpayers started on 1 November last year.

The problem is that not only are the loss ring-fencing rules (unsurprisingly) unpopular with residential property investors, the proposed legislation has drawn such heavy criticism for the (lack of) quality of its drafting, that Inland Revenue has apparently rewritten it entirely. The FEC is not due to report back on the loss ring-fencing legislation until June and it could be another couple of months after that before the legislation is enacted.

Meantime, Inland Revenue is about to shut down for a week as it prepares to launch the latest and most significant stage of its Business Transformation programme. Although legislation and policy are distinctly separate from the daily operations of Inland Revenue, there is a sense that its principal focus at the moment is the Business Transformation programme. Consequently, whether it is actually ready to draft and implement significant policy changes at this time appears questionable.

The dissenters to the majority opinion did so on the basis that the policy over the past thirty years of making incremental changes to the taxation of capital has “served New Zealand well”. And another incremental change appears where we will ultimately end up. At the same time, however, as David Hargreaves observed it means “as a country we obviously don’t want to deal with the broader issues of taxation and taxing wealth.” Which as David concluded is indeed a little depressing.

[1] Para 42, chapter 5, Final Report Volume 1

[2] See table 8.2 in Chapter 8 of the final report

This article first published on Interest.co.nz

16 Mar, 2019 | Tax News

Imposing a Digital Services Tax will concentrate the tech giants’ minds on their woeful response to the Christchurch massacre.

What to do about Facebook, Google and Twitter’s reprehensible failure to stop the live-streaming of a terrorist atrocity and the dissemination of vile images? How about a 20% Digital Services Tax, for starters – effective as of 1.30pm NZT, Friday 15th March 2019, just before the shooting began at Al Noor mosque?

You might have forgotten it now, but in the same week as the Tax Working Group (TWG)’s final report was released, the government raised the possibility of a 3% digital services tax levy on the revenue of the tech giants. This proposal is in response to the kind of tax planning which enables Google to extract as much as $600 million in ad revenue from New Zealand each year yet pay minimal income tax (just $393,000 for the year ended 31st December 2017).

The proposal got drowned out by what now looks like an absurd over-reaction to the TWG’s recommendations on capital gains tax. Last Friday we got a brutal lesson in what really is the biggest assault on our Kiwi way of life.

So why a Digital Services Tax?

The tech companies’ woeful response to Friday’s massacre deserves a firm response. If there’s one thing that has been a constant in my near 35-year tax career it’s that the threat of paying tax concentrates people’s minds wonderfully.

A retrospective 20% charge potentially represents $200 million in tax each year. Such a hit to their bottom lines will force Google (owner of YouTube), Facebook and Twitter to address their inadequate response to the attacks. If the carrot of a lower rate is offered on condition of improved moderation, watch how quickly the algorithms get changed.

As for the retrospective application of the tax? Tough. Unlike the 50 dead and their grieving families, tech company executives and shareholders get to carry on with their lives. Besides, no-one seemed too bothered about the change of law in 2013 which at a stroke handed thousands of investors in foreign superannuation schemes retrospective tax bills. Those affected by that law change were people who had chosen to make their lives in New Zealand.

In contrast the tech giants expect their intellectual property and frankly oligopolistic practices to have the full protection of New Zealand’s courts, yet simultaneously arrange their affairs to minimise their tax bills. After the slaughter at Al Noor and Linwood mosques this cannot be allowed to stand. All the time the images were being live-streamed and disseminated Facebook and Google were making money – effectively blood money.

Of course, another way to punish Facebook and Google would be for us all to stop using their sites and for central and local government to stop advertising through both companies. The problem is that in an incredibly short period of time Facebook and Google have so embedded themselves in our social and commercial infrastructures that removing them is practically impossible.

So if we can’t live without them but we want better behaviour then hitting then in their back pockets through taxation seems the appropriate response. In this regard, think of the Digital Services Tax as akin to the corrective taxes recommended by the TWG. To this end the government should include in any legislation the ability to change the tax rate by Order in Council.

Maybe applying the tax raised to improving mental health outcomes would help those struggling with the aftermath of the attack, and the myriad other mental health issues triggered by social media.

Facebook and Google will probably respond that they didn’t foster the racism which fed the killer’s rancid imagination. And yes, changing that culture is on us. But as we deal with that confronting process Facebook and Google can start paying their way and help with cleaning up their own messes. What have we got to lose?

This article first appeared on The Spinoff.

14 Mar, 2019 | Tax News

SkyCity’s moves to set up an offshore online gambling subsidiary throw up a huge range of questions about just how tax should work in the digital age, writes tax consultant Terry Baucher.

The news that SkyCity is voluntarily paying perhaps as much as $40 million in “tax” sounds like someone actually took seriously the remark “Well if you like paying tax so much why don’t you pay extra?”

In fact, what it illustrates is that for a supposedly “simple” tax, GST can get very complex, particularly when it involves services and an offshore entity. So, what’s going on here?

As it says on the tin, GST is a tax on goods and services. It’s pretty easy to work out what’s due and who’s liable when goods are involved. For GST purposes, if the supplier is resident in New Zealand and supplying goods and services to a New Zealand resident, then GST is payable.

Things get more complicated once services are involved, particularly with services delivered online to a New Zealand resident by providers with no physical presence in New Zealand. Resolving the complexities this creates has resulted in a series of amendments to GST as Inland Revenue and the Government try and keep up with the impact of the digital economy. The so-called “Netflix Tax” changes introduced on 1 October 2016 are one such example. As a result, GST is now payable on your Netflix subscription.

Online gambling is just the latest instance of this problem of GST and online services. Betting and gambling are treated as a service for GST purposes and therefore subject to GST. For SkyCity there are big numbers involved: according to its financial statements for the year ended 31st December 2018 it paid just under $100 million in “Gaming GST”.

The world-wide value of online gambling was estimated at US$45 billion in 2017 and this is expected to more than double by 2024.

It’s therefore unsurprising that SkyCity have decided to enter this market. It simply can’t afford not to do so. But since online gambling in New Zealand is at present illegal, SkyCity has to use an offshore subsidiary apparently based in Europe. This subsidiary is therefore a non-resident for GST purposes.

The GST headache for SkyCity is whether its offshore subsidiary must pay GST on the value of the gambling done in New Zealand. (Income tax will only become payable in New Zealand when profits are remitted to New Zealand). If the servers are situated outside New Zealand does that even mean the gambling is happening in New Zealand? Can Sky City’s subsidiary even identify those gamblers if they use VPNs, which can hide a user’s location? And even if it can identify those gamblers located in New Zealand, there remains the most interesting ethical question of all: should SkyCity’s online betting subsidiary pay GST on an activity which is at present essentially illegal in New Zealand?

Surprisingly, the answer to that last question isn’t as clear cut as you might expect, but the short answer is “Yes”. (In a perhaps too on the nose precedent, the High Court in England ruled that an illegal bookmaking business represented a taxable trade even though it involved illegality).

For SkyCity these considerations are compounded by the fact that the penalties for getting its GST calculations wrong are significant: an immediate late payment penalty of 5% plus 1% per month thereafter and use of money interest at 8.22% on the late paid GST. In a worst-case scenario, it could even face shortfall penalties of 20% of the GST due if Inland Revenue thought it had either not taken reasonable care or its tax position was unacceptable. Throw in SkyCity’s disclosure requirements as a listed company and overall, it’s not hard to see why the company felt it should adopt the position of voluntarily paying “tax.” What would be interesting to know is what period the suggested voluntary payment covers. Six months? A year?

It’s quite likely the GST issues involved in online gambling will be resolved by some sort of legislative patch. Nevertheless, a bigger tax question remains, one not really addressed by the Tax Working Group. In an increasingly digital economy, does GST, a tax designed for a non-digital economy, really have a long-term future?

This article first published on The Spinoff

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.