Inland Revenue regularly releases Technical Decision Summaries (TDS). These are summaries from its Adjudication Unit in relation to dispute cases of interest between Inland Revenue and taxpayers. These give a good indication of Inland Revenue thinking around particular topics and how it might react to a transaction.

TDS 22/21 released last week is particularly interesting. It involves a two-lot subdivision carried out on a property by a taxpayer. He had initially purchased the property when working offshore for the purpose of renovating and extending it to live in with their extended family. Once the property was purchased, the extended family moved into the dwelling and the taxpayer joined them later on his return to New Zealand.

He then started planning to extend the property, but it emerged that there were problems with drainage and asbestos. Instead, it was suggested that the taxpayer should subdivide the property into two lots, constructing a new dwelling on each lot. And that’s what happened, during which time he was working overseas and visiting intermittently. Once one of the new properties was constructed, he occupied it for eight months. Shortly after the subdivision was completed one property was sold and the taxpayer and his extended family continued to live in the other property for a further five years.

Inland Revenue argued that the taxpayer had entered into an undertaking or scheme with the dominant purpose of making a profit under section CB 3 of the Income Tax Act. This provision is outside the normal land tax provisions, which is slightly unusual. Inland Revenue also ran the argument that the property was acquired for the purpose of intentionally disposing of it under CB 6, which is within the land taxing provisions. The question arose whether there was relief available because it was a main home. And finally, Inland Revenue also raised the question whether the sale of the subdivided lot and the property was subject to GST.

It seems part of the issue here may have been Inland Revenue just didn’t believe what they were being told. The Technical Decision Summary reasons for the decision opens with a reminder that the onus of proof is on the taxpayer to prove that an assessment is wrong, why it is wrong and by how much it is wrong.

This case turned out to have a good outcome for the taxpayer, because the Adjudication Unit ruled that the taxpayer did not enter into an undertaking or scheme for the dominant purpose of making a profit. Therefore, the gain wasn’t taxable under section CB 3. The Adjudication Unit ruled the taxpayer acquired the property for the sole purpose and with the sole intention of creating a home for themselves and their extended family. Therefore, the sale of the second lot was not taxable under section CB 6. It followed that as the property had been occupied mainly as residential land prior to subdivision, an exclusion applied. Finally, the taxpayer did not carry out a taxable activity for the purposes of the Goods and Services Tax Act, so no GST applied to the transaction.

The taxpayer won on all points. But there are several interesting points here. First is that Inland Revenue even took the case and the arguments it ran. This transaction appears to have happened before the Bright-line test was introduced, the TDS isn’t clear about the timing. The attempt to apply section CB 3 is unusual.

Secondly it highlights that Inland Revenue is paying attention to just about any property transaction and it’s prepared to use all provisions that are available to it. The case is a reminder to keep good records. I think the taxpayer struggled initially because not enough evidence was available, but they were eventually able to persuade the Adjudication Unit of what had happened.

Tax professionals vote for a Capital Gains Tax

Moving on, the Technical Decision Summary does point to an ongoing strain within the tax system around the taxation of capital gains. In many jurisdictions that have capital gains taxes the issue we’ve just been discussing would be not on whether or not the transaction was taxable, which is an all-or-nothing proposition, but what proportion might be taxable.

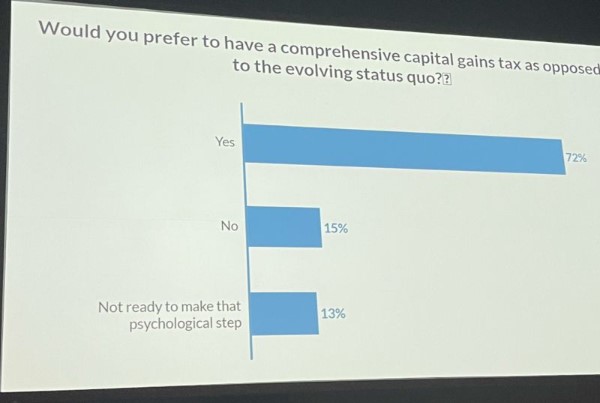

It’s therefore interesting to see that at the Chartered Accountants of Australia and New Zealand’s National Tax Conference recently, a poll was conducted on the introduction of a capital comprehensive capital gains tax. The question was put would you prefer to have a comprehensive capital gains tax as proposed to the evolving status quo, which is actually a very generous description of the evolving state, still, to be frank.

(Photo by Richard McGill of PwC)

I wasn’t at the conference. I would have voted yes, although plenty of caveats around how we might go about it. It’s also tempting to respond, “Well, that is a lot of self-interest by accountants voting for such a measure.” I know that I’ve seen similar comments pointing out when I raise the issue that of course I would support it because I get extra work out of that. I find it ironic to be accused of acting out of self-interest when the flipside of it equally applies people who don’t want a capital gains tax would also be saying so out of self-interest. Self-interest arguments cut both ways, in my view.

I do happen to think that self-interest is a problem in the tax system around this whole area. It’s very difficult to see how parliamentarians owning substantial capital assets are going to ever going to vote for something which is directly against their own self-interests.

The feedback from the CAANZ conference was that it’s necessary to keep our tax system comprehensive and robust. And it would actually simplify quite a lot of measures that we see right now. For example, if you had a capital gains tax, you wouldn’t have to work through the bright line test and its various iterations. You could remove the foreign investment fund rules, another set of rules which are complex and not well understood. And you would also probably remove, or certainly reduce the need for measures such as restricting interest deductions. This has been introduced partly as a response to the absence of a capital gains tax.

In my view, there’s a lot of distortions in the tax system because we don’t tax capital gains, and we are seeing more and more of that. At last year’s International Fiscal Association’s annual conference many of the issues we were debating really revolved around the strains on the edges of the tax system produced by not taxing capital gains.

A CGT is not going to be popular with politicians or for those who would be affected. But the rest of the world manages these strains. So, to pretend that we can get by without a CGT and continue the current incoherent approach to taxing capital gains, is a position that just simply isn’t sustainable in the long term.

Updates on global tax coordination

Now, moving on, in international tax news the OECD released its latest corporate tax statistics. There’s a lot to consider here which I’ll discuss next week.

The OECD also released data relating to the latest Mutual Agreement Procedure statistics covering 127 jurisdictions and practically all the mutual assistance cases worldwide. These Mutual Agreement Procedure cases arise when two or more tax jurisdictions want to resolve the tax treatment of a transaction or entity where each jurisdiction thinks they have priority. Transfer pricing issues are often involved.

According to the OECD, approximately 13% more Mutual Agreement Procedure cases were closed in 2021 than in 2020. But fewer new cases started this year, which is a small, unusual trend given the internationalisation of the global economy. But these Mutual Agreement Procedure cases do take some time to resolve, on average, about the 32 months for transfer pricing cases and 21 months for other cases.

But amidst all this, there’s some good news, including an award for Inland Revenue which together with Ireland was awarded the prize for the most effective caseload management. The most improved jurisdiction was Germany, which closed an additional 144 cases with positive outcomes – that is, the matter was fully resolved.

These awards seem a bit of fun, but actually it’s a pretty important matter because with the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting and the hopefully soon introduction of the Two-Pillar international tax agreement, the role of Mutual Agreement Procedures in resolving disputes is going to be important. It’s encouraging to see jurisdictions are making progress and cooperating better

Paying tax and the right to vote

And finally this week, the Make it 16 win in the Supreme Court over the potential voting rights of under 18 caused quite a stir. David Seymour of ACT jumped in with a rather ill thought out comment “We don’t want 120,000 more voters who pay no tax voting for lots more spending.”

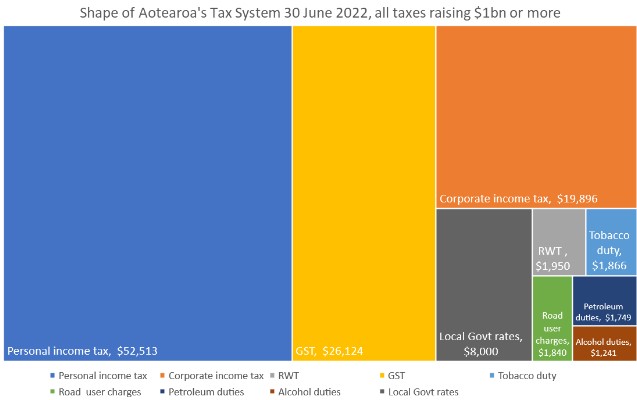

From the first time a child uses their pocket money to buy an ice cream and dairy, they’re paying tax. It’s called GST, which at over $26 billion is a quarter of the Government’s tax revenue. And as I pointed out on Twitter, lots and lots and lots of under-18s pay GST.

(The total of local government rates is an estimate. It appears the true figure is just over $7.3 billion)

The Make It 16 group made an Official Information Act request to Inland Revenue about how much tax 16- and 17-year-olds pay. And according to Inland Revenue over 94,600 16 -and 17-year olds paid a total of $82 million in income tax during the year ended 31 March 2022. That’s not an insubstantial amount of money (and doesn’t take into consideration the GST they also paid).

Given that 16 is the age of consent and 16 year-olds may drive, I don’t see much logic in saying that’s too young to vote. The kids are all right in my book.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!