- Shining some light on the impenetrable maze of the financial arrangements regime

- Inland Revenue brings estate agents into line

- Google NZ’s latest results show the need for international tax reform

Transcript

The financial arrangements regime is one of the most complicated parts of the income tax. It has huge scope but is not particularly well known. And until very recently there has been little practical guidance on the regime from Inland Revenue. Fortunately, all that is changing now. In the past couple of years, Inland Revenue has issued a series of Interpretation Statements which have clarified how the regime operates.

This week it’s released a revised draft Interpretation Statement on the critical issue of cash basis persons and how the regime applies to these people. Now, this is particularly important guidance because a person who is a cash basis person accounts for income and expenditure from a financial arrangements regime on a cash or realised basis rather than the at accrual or unrealised basis. The draft statement also sets out the adjustment that must be made when a person ceases to be a cash basis person and then has to switch to accounting for their financial arrangements income and expenditure on the accrual or unrealised basis.

There’s an accompanying fact sheet, so you don’t have to go through the whole full 33 pages of the Interpretation Statement. Page four of this fact sheet has a very useful flowchart, setting out process for determining if a person is a cash basis person. In summary, a cash basis person is someone who does not hold financial arrangements which exceed either of the following thresholds $100,000 of income and expenditure in the income year or the total value of these financial arrangements is under $1 million.

In relation to the $1 million threshold, the taxpayer must be below that threshold throughout the entire income year. So, if you cross it for just one day, that’s it, and you may be in the regime. If both those thresholds are exceeded the person cannot be a cash basis person.

Then there’s the second test you apply, if neither, or only one of the thresholds is exceeded. In this case you still have to check whether the difference between income and expenditure calculated on the cash basis, realised basis and under the accrual or unrealised basis does not exceed $40,000. This is what they call the deferral threshold. If it does, then the cash basis cannot apply. Now this $40,000 deferral threshold is often overlooked when people are considering whether or not they’re within the cash basis person. The Interpretation Statement has some good, worked examples how this applies.

If someone falls into or out of the cash basis status, they have to carry out a cash basis adjustment. And again, the Interpretation Statement has a good, detailed example. One of the issues that many people encounter is exchange rate fluctuations, which can put people unexpectedly into the regime and therefore have unintended consequences.

The classic examples I’ve seen are with people holding overseas mortgages against an overseas investment property and the fluctuation of the thresholds. Brexit in particular was one of those events that caught quite a number of people. Incidentally, this is perhaps why one of the examples here refers to the 2016-17 tax income year when Brexit happened.

The Interpretation Statement has a useful tip about financial statements subject to exchange rate fluctuations. It suggests identifying when the New Zealand dollar was at its lowest point compared to the foreign currency in the year and calculate the value of the New Zealand financial arrangements at that time. That’s a quick way of determining the highest possible value of the arrangement during the income year, assuming the principal hasn’t changed materially.

Paragraph 69 of the Interpretation Statement also includes some nice examples of why people might adopt the accrual basis from the outset. Doing so might resolve the problems around cash basis adjustments or they might want to actually bring the income or expenditure such as an unrealised exchange loss into account immediately.

The financial arrangements regime is actually another example where thresholds have not been frequently adjusted. These particular thresholds were last set at the start of the 1997-98 income year. They now catch far more people than were probably ever intended. Using the Reserve Bank calculator based on CPI, those absolute thresholds now would be $170,000 instead of $100,000, $1.7 million instead of $1,000,000 and the deferral threshold would be $70,000. If you use the Reserve Bank’s housing inflation calculator, then the income expenditure threshold would be $560,000, the absolute threshold for all financial arrangements would be $5.6 million and the deferral threshold $225,000. So whichever inflation indicator you’re using an adjustment is therefore well overdue.

The point here that frustrates me is that there’s a persistent theme across the tax system, where thresholds are not adjusted for inflation frequently enough. It’s a sneaky way for governments of both hues to collect additional revenue without too much notice. Quite apart from these financial arrangements regime thresholds, the income tax thresholds were last adjusted in 2010 as is well known.

The abatement threshold for working for families, that is the threshold above which abatement clawback applies hasn’t kept up inflation. By my calculation, I believe it’s now lower than what someone on minimum wage would earn. And the threshold for student loan repayments above which 12% is deducted from your income, that hasn’t been adjusted for some period. Governments really ought to be much more proactive about changing these thresholds. There’s actually a good political point here, in that doing so would de-politicize the issue. However, as I said, governments appear to quite like this sneaky increase in revenue.

Rant aside, it’s good to see guidance like this from Inland Revenue, the fact sheet is particularly useful. No doubt we’ll see more guidance on this area, but in the meantime, you should definitely have read this because this is a complicated regime and it catches far more people than you would expect.

Targeting real estate agents

Moving on, there was an interesting little piece in Stuff this week regarding the success of Inland Revenue’s campaign about real estate agents claiming personal expenditure when they shouldn’t as an attempt to reduce their tax bills. Inland Revenue advertised it was looking at estate agents’ expenditure which it thought was excessive.

We haven’t heard too many stories about who has been caught by this, but Inland Revenue took the view that focussing some attention on the issue would encourage others to behave. Basically, what was happening that some agents were understating income and overstating expenses. And it appears now over 90% of the tax returns for the March 2021 income year have been filed, Inland Revenue compared the results from that sector relative to earlier tax years and it has seen these trends reverse, particularly in relation to what it called private expenditure.

One of the one of the issues is claims for gifts, personal clothing and grooming and entertainment expenditure. And there was also under-reporting for GST purposes. Some people apparently used a net amount in their bank account for GST purposes. This is actually a really good example of Inland Revenue applying the blowtorch by saying “We have got the data we can match this and don’t think we’re not noticing what’s going on here”. So good to see on that.

There’s an interesting point here which I think Inland Revenue should issue some guidance on. And that is where someone who is working with clients and has to look professional, and therefore purchases smarter clothes for that role, what proportion may be claimable?

I remember a very famous case on this issue from my time in the UK: Mallalieu versus Drummond. A female barrister claimed a deduction for some very sombre, dark clothing that she wore only in court. She didn’t win her case, but the point still stands if you are purchasing clothes which are only use work to what extend is that deductible. And I think Inland Revenue should come out and clarify what it thinks about that.

Incidentally, Mallalieu didn’t involve the astonishing Section 189 of the Income and Corporations Taxes Act 1970. This allowed an individual to claim an expense for “keeping and maintaining a horse to enable him to perform the same or otherwise expend money wholly, exclusively unnecessarily the performance of said duties”. Yes, the UK tax legislation in 1970 (and actually again in the 1988 consolidation), had a reference for a specific deduction for a horse. That provision actually wasn’t updated until 2003. So, if you think our tax legislation is a bit arcane to spare a thought for the UK.

How much of Google’s NZ revenue escapes the NZ tax net

International tax has been in the news lately because concerns are starting to grow as to whether the tax deal signed last year by 130 countries, including New Zealand, is actually going to be implemented. Inland Revenue currently has a major issues paper out on the topic, submissions on which close next week.

The Revenue Minister David Parker was speaking to the Finance and Expenditure Committee this week. From his reported comments he expressed some concern about whether the so-called Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals would come into effect.

But the need for those rules to come into place was underlined, in my view, by Google New Zealand’s December 2021 results, which were published on the Companies Office website yesterday.

Google’s revenue, as reported for income tax purposes, rose from $43.8 million in 2020 to $57.8 million in 2021. Its pre-tax profit went from $10.2 million to just under $18 million, and Google ended up with $3 million corporate income tax for the year ended 31st December 2021 once you take into account timing adjustments.

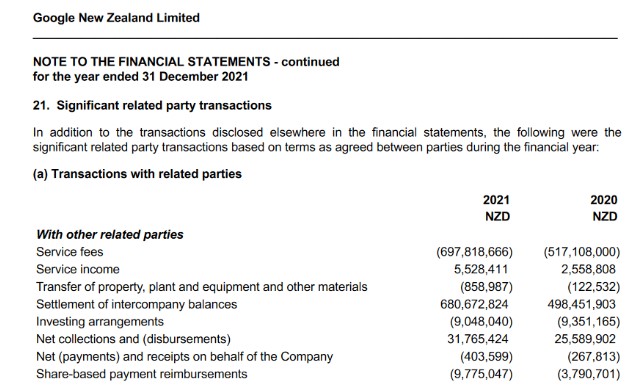

But what’s really interesting when you drill into the financial statements is what’s going on with related parties. The notes to the financial statements disclose the transactions with the related parties. We can see that the service fees Google New Zealand paid to other overseas companies in the Alphabet Group (the owner of Google) in the year amounted to $697.8 million. Now that’s up from $517.1 million in 2020.

This gives you an indication of the level of advertising revenue activity actually going through Google New Zealand. These service fees are perfectly valid although Inland Revenue will no doubt have its transfer pricing specialists run their eye over these fees. There may be some queries going on, we don’t know as the accounts are silent on that. But the level of activity here indicates how much advertising revenue is going through Google New Zealand and how much is being paid offshore as a legitimate deduction for income tax purposes.

But it shows the arrangements that are in place that enable substantial amounts of advertising revenue pass through Google New Zealand, but it finishes up paying only $3 million in income tax. It does pay a substantial amount of GST, according to the financial statements the GST payable has on 31st of December 2021 was just over $21 million. This would indicate a very significant level of taxable supplies deemed to be made in New Zealand. But it’s likely that the GST Google New Zealand is charging is probably also being claimed by New Zealand businesses. In other words, it’s largely a net zero-sum game.

Anyway, my hope is that the international tax deal will go through. There is politics being played in America, no surprises there, but also in Europe where the EU is trying to get unanimity amongst its 27 member states. It’s a question of “Watch this space” for developments. But Google gives you an example of why we would want to know more about what’s going on here and hope the deal goes through.

International Tax was a topic at the International Fiscal Association Conference held last week. As this was held under Chatham House rules, I can’t really say too much about it, but there were a lot of interesting topics from excellent presenters and a fairly lively debate on a number of topics including international tax.

Another featured topic was the controversial dividend integrity and personal services attribution rules, and that had probably the liveliest debate. The key takeaway for me from that particular session was a comment that these proposals show the limits of what can be done in the current tax system without a capital gains tax system. Because when you sit back, the cause of controversy there was that there were potentially capital transactions happening, which would be tax free under our present regime. However, Inland Revenue was looking at this and saying, “These transactions mean tax is not being paid”.

Now, the other take away I had, is that this tension is just getting worse and isn’t going to be resolved until the matter of taxing capital gains is resolved as well. I’m on record as supporting a capital gains tax. It probably is needed not so much as a revenue raiser but to preserve the integrity of the tax system. Because when you have such a hole in your base, it will be exploited. Incidentally, this means you can’t really argue, you’ve got your tax system is broad based. There are measures in place to deal with this, but we are talking about patches upon patches.

And so, this debate, which is going on for all the time I’ve been here in New Zealand but has intensified in recent years, is going to continue. At some point the issue will have to be grasped and resolved. No, it won’t be terribly popular. But if you want to maintain the integrity of the tax system, it seems to me that some form of capital gains tax is pretty near inevitable.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time Mānawatia a Matariki, enjoy Matariki!