Post Budget analysis

- indexing thresholds regularly

- GST on transitional housing

Welcome back everyone. Apologies for the COVID induced intermission and thank you for all those good wishes for my recovery along the way.

An awkward discussion

On the morning of the Budget lockup, I had an awkward call with the client over an unpaid bill. The matter was resolved, but it struck me then and now, as kind of symbolic of the general approach by governments to the question of tax. It’s a very awkward conversation that they really would rather not have. This seems really surprising when you consider that budgets involve spending and government expenditure in the current Budget to June 2025 will be close to $140 billion. To pay for this the expectation is that tax revenue will be about $123 billion during that same period.

Tax is by definition a big part of governments’ budgets, because it raises the majority of the revenue which enable them to run the country. But as I have realised when attending 14 Budget Lockups we never talked very much about tax. On Budget Day, it’s all about splashing the cash. The accompanying ministerial releases are about how money is spent will be spent on this or that particular project. Often you’ll find that the bad news about student loan increases interest rate increases is tucked away on the second page of a ministerial press release.

This approach strikes me as highly symbolic. And by the way it’s the same for governments of whatever hue. Whether National or Labour-led both have pretty much the same approach “Here’s all this lovely cash we’re spending and tax, well we’re doing one or two things minor things.” This year was actually quite unusual because of the focus around the tax threshold changes.

Never mind the spending, where’s the tax legislation?

The other thing which is also slightly unusual as well is the relevant tax legislation isn’t released to us as part of the Budget Lockup. Now you might think, as I do, that when you’ve got a whole pile of tax experts locked up in a room, passing them the legislation which supports the main initiatives might actually be quite a useful thing for broadening people’s knowledge, but actually no, that’s not the practice.

Consequently, some of the detail which was released after the Budget Lockup contained a few surprises. Being cynical about it, the reason why governments are a little bit wary about giving people too much information beforehand is that the required Regulatory Impact Statements contain a lot of detail about tax initiatives and some of that detail is rather awkward for governments in general. To repeat my earlier point, generally speaking discussions about tax are often an awkward conversation governments would rather not have.

The devil in the detail…

As always, Regulatory Impact Statements (RIS) contain some very interesting details, and this is very true of the two that were released in in relation to the Budget. As is well known the tax cuts announced in the Budget involved increasing thresholds for the first time since October 2010. What was not explained during the Budget Lockup and actually only emerged afterwards was that some of the secondary thresholds, such as those relating to fringe benefit tax and employer superannuation contribution tax aren’t going to be adjusted until 1st April next year. The reason given for that is complexity of doing so now.

In fact, in the RIS on the personal income tax threshold changes, Inland Revenue and Treasury officials recommended that the tax threshold adjustments didn’t take place until 1st October. This would allow time for payroll providers and Inland Revenue to get ready and have all the thresholds ready to go as of 1st October. This was what happened back in 2010, when tax thresholds were last adjusted. The announcement was made in May as part of the Budget but didn’t take effect until 1st October. Incidentally, that also gave everyone 4 1/2 months to get ready for the increase in GST from 12.5% to 15% which also took effect on 1st October 2010.

The personal income tax change RIS’s begins with the Problem Definition

“When prices and income rise from generalised inflation and wage growth, but nominal income tax thresholds remain unchanged, individuals end up paying a larger proportion of their tax of their income in tax. Over time, this may result in the amount of tax being paid at different income levels not aligning with the Government’s intentions.

As you can imagine, if you’ve not done anything in this space for 14 years, it can get very problematic. The RIS primarily discusses National’s election proposals, but also references the ACT Party’s election proposals because, as the paper notes

“In the National-ACT Coalition agreement, a commitment was made to ensure the concept of ACT’s income tax policy are considered as a pathway to delivering National’s promised tax relief subject to no earner being worse off than they would be under National’s plan.”

The starting point for Treasury and Inland Revenue officials was Nationals tax proposals, but they also considered variations on the ACT plan, which if you to quickly recall, involved compressing the five current tax brackets down to three combined with a Low and Middle-Income Tax Credit.

Officials also considered several cost savings initiatives, one of which was deferring implementation until 1st October 2024. They also recommended not proceeding with the proposed expansion of the Independent Earner Tax Credit.

“The long-standing view of officials has been the objective of improving work incentives could be achieved more effectively by removing the IETC and making other changes to tax and transfer settings for the same fiscal cost.”

Removing the IETC was something I thought was going to happen to help pay for the tax threshold adjustments. I note by the way, that subsequent to the Budget, Steven Joyce said he would have done that as in fact he proposed to do so back in May 2017.

But as we know, Cabinet went along with National’s plan and chose an implementation date of 31st July. According to the officials, the estimated cost over the forecast period to June 2028 of the threshold adjustments is $10.3 billion. Officials thought they could have reduced that cost by between $1 to $2 billion through some adjustments.

The scale of fiscal drag

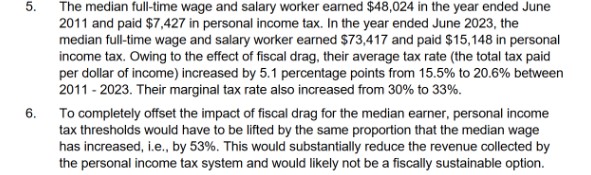

Paragraphs 5 and 6 of the RIS underlined the question of just how much of an issue fiscal drag had become.

As the RIS notes, one of the objections about not making regular changes in thresholds is that the “increase in tax from fiscal drag is arguably less transparent than explicit changes to tax settings and may engender less public debate.” Furthermore, when inflation exceeds wage growth, people’s tax burdens increase, even as their ability to pay for goods and services decreases because of inflation.

The conversation we’re not having

But tax is always politics and as paragraph 17 of the RIS notes;

“The desired level of progressivity in the personal tax system is a judgement for ministers to make. Any decision to address fiscal drag by adjusting thresholds will also depend on the revenue needs of the Government and their economic goals.”

This is the discussion we’re not really having. We, the public are saying we’d like this, that and the other to be spent on various public services such as hospitals, schools, roads, pensions. The Government is saying ‘fine, we’ll do that’ but isn’t really talking to us on a serious level about the level of tax we need to meet those demands. If more services are demanded either tax is going to have to be increased or other services must be reduced. That’s a debate that’s not happening, but that’s politics and it’s the same the world over. I’m seeing the same thing play out in the current UK election.

Simplifying the tax thresholds

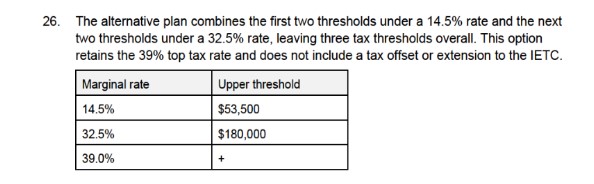

Interestingly, apart from considering ACT’s proposals, officials developed an alternative which would also have reduced the five tax brackets to three.

The key difference between this proposal and that of the ACT Party is that it would have retained the 39% rate. It would also not have included an extension of the IETC, or the tax offsets proposed by ACT.

Giving with one hand, and taking with the other

The RIS relating to the increase in the In-Work Tax Credit to $25 per week highlights an issue which I actually raised with the Minister of Finance in the Budget Lockup, and that’s that is the interaction of abatements and low thresholds. Currently, the family income threshold for those receiving Working for Families’ tax credits (WFF) is $42,700. This threshold has not been increased since 1st July 2018. Above that threshold WFF are abated at a rate of $0.27 on the dollar. As I told the Minister of Finance, this means that people on very modest incomes are on a higher effective marginal tax rate than her. That did not go down well, to be honest.

As the RIS shows the effect of the abatement regime for the 170,000 families benefiting from the package is that though the Government might talk about an increase of $25 per week, on average the net amount received will be $16.97 per week. The difference is the the effect of abatement.

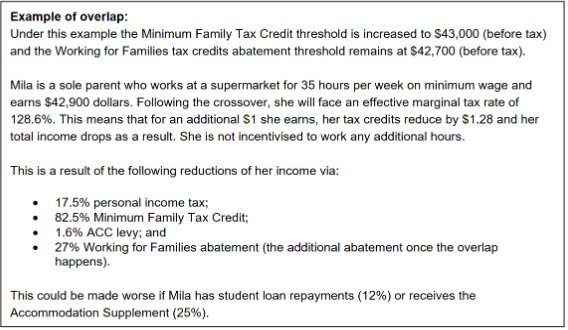

The RIS also notes that unless something is changed the minimum family tax credit threshold, which is increased annually, will soon overlap the threshold at which WFF abatement starts. On present settings this expected to happen on 1st April 2027. As the RIS notes this will result in WFF customers “facing effective marginal tax rates of well over 100%.”

How someone earning $42,900 could have a marginal tax rate of 165.6%

Page 11 of the RIS has the following example illustrating the pending overlap problem.

If Mila was receiving the accommodation supplement, that would be another 25% and if she had a student loan 12% would be deducted. In a worst-case scenario Mila’s effective marginal tax rate would be 165.6%.

Time to regularly index income tax thresholds?

So that leads on to a question which we’re starting to hear more frequently – should we be increasing thresholds regularly? My longstanding view is yes, because it deals with this question of fiscal drag and it’s more transparent. When governments rely on fiscal drag by not adjusting thresholds regularly that is quietly increasing the tax take in the hope nobody pays too much attention to it, other than tax geeks like me. But this approach leads to an ever-increasing problem which after a while means full indexation becomes too expensive as officials noted.

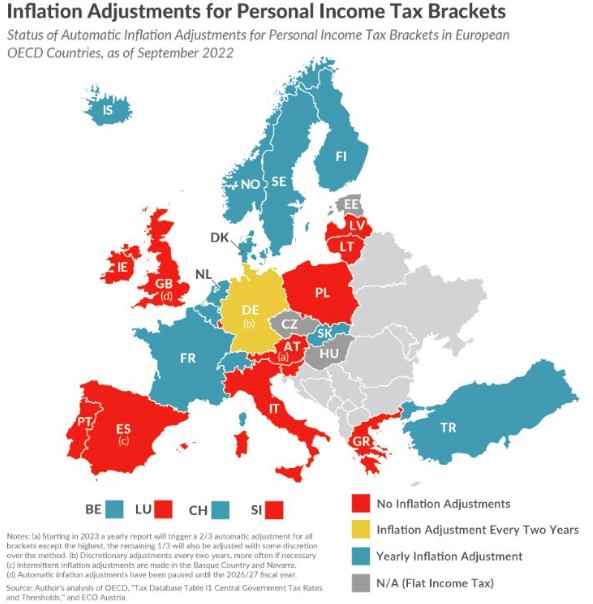

Interestingly, Dr Benjamin Walker of BDO published a LinkedIn post this week with a map illustrating what happens in European OECD countries around indexation.

As you can see a number of countries do regularly adjust thresholds. Germany does it every two years. Several, such as France, the Netherlands, Denmark and Denmark, do so annually. Other jurisdictions such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Estonia have a flat or single income tax rate so fiscal drag is less of an issue. And then there are other countries that presently don’t index thresholds such, such as Italy, Spain, Ireland and the UK.

I would add in relation to the UK, they’re statutorily they are required to increase thresholds and personal allowances each year, but Parliament may override that as part of its annual budget. And that’s actually been done recently and has been in place for several years. The Conservative Government has therefore deliberately relied on fiscal drag to help increase the tax take. As a result, there are increasing pressures around some very high effective marginal tax rates.

Incidentally, some of the tax discussion coming out of the British election is quite interesting and I’ll probably cover it off in a future podcast. As an aside, I’ve had three UK related assignments come in this week, so UK tax is not as an abstract an issue for New Zealanders as you might imagine.

Another awkward conversation to be had

My view is that thresholds should be regularly indexed for inflation. But we also really need to have a serious discussion about the relationship between abatement rates on benefits and tax credits and the resulting very high effective marginal tax rates for workers on fairly low and sometimes below average wages.

As Geof Nightingale said in the recent podcast with him, Rob McLeod and Robin Oliver, the biggest surprise for him about our tax system is how little discussion goes on around this particular issue which is quite scandalous. When people hear a lot about high tax rates they think of 39% and happening to people on very high incomes. I believe most people would be absolutely staggered to find out that someone on $42,900 per annum could have a marginal tax rate of up to 165%.

GST and landlords supplying properties for use as transitional housing

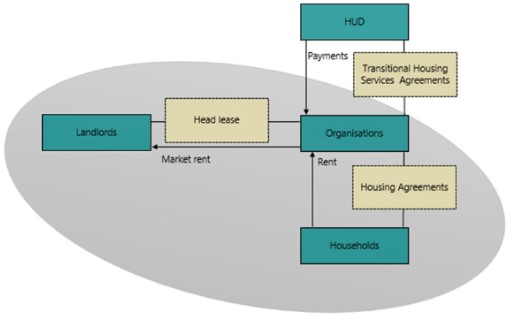

Finally this week, Inland Revenue has released an interesting Operational Position together with three public rulings on the GST treatment of landlords who supply properties for use as transitional housing. Organisations that provide transitional housing services on behalf of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) generally lease properties from landlords under a head lease and pay market rent. Then those organisations will enter into various agreements with the transitional housing tenants.

As always housing is a big topic, and the arrangements involve somewhat tricky GST issues. These binding rulings and Operational Position have been issued to clarify the GST position because it appears that several landlords adopted an incorrect position.

Essentially the Operational Position draws a line under what’s gone on previously and gives guidance on how Inland Revenue is going to apply the technical view set out in the three associated rulings where landlords have previously taken incorrect tax positions. In most cases Inland Revenue is unlikely to issue assessments regarding incorrectly claimed input tax deductions. Each situation will be fact dependent.

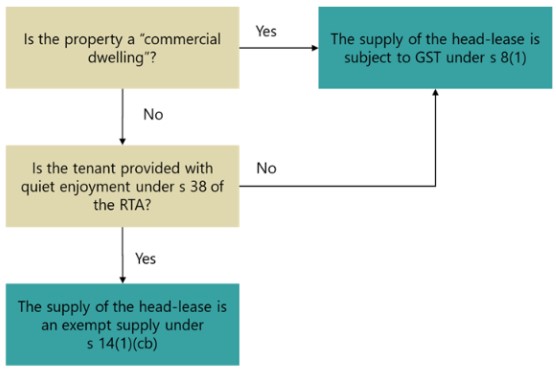

As is now standard practice, there’s a helpful fact sheet which summarises the position in the three binding rulings. The GST treatment depends on whether the buildings leased are “commercial dwellings” and the terms of the housing agreement. If the properties are provided to the tenants with the right to quiet enjoyment as defined in section 38 of the Residential Tenancies Act, then it’s an exempt supply and GST will not apply. If there is no right to quiet enjoyment, then GST will apply. (In some circumstances it may be possible to use the reduced 9% or 60% of the full GST rate).

So that’s a quick summary of the of the position. Obviously Inland Revenue has encountered a number of issues here and decided to clarify its view on the proper interpretation of the legislation.

Well, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.