The IMF calls for a comprehensive CGT

- changes ahead for the FIF regime.

- a novel proposal for funding NZ Superannuation.

Every year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) undertake an official staff visit or mission to New Zealand as part of regular consultations under Article IV of the IMF Articles of Association. Each IMF mission speak with the Minister of Finance, Treasury officials and other persons – economists, academics and the like about the state of New Zealand’s economy and related issues. At the end of the visit the Mission then issues a short concluding statement of its preliminary findings.

The IMF will then prepare a lengthier report setting out its findings in more detail which we can expect to see in a couple of months time.

“A window of opportunity”

After noting it expects real GDP growth to rise to 1.4% for this year and then to 2.7% in 2026 the Mission noted:

“The macroeconomic environment provides a window of opportunity for New Zealand to consider broad based reforms needed to address medium- and long-term challenges, including to secure fiscal sustainability, boost productivity, address persistent infrastructure and housing supply gaps, and initiate early dialogue on population aging.”

“A comprehensive capital gains tax”

My understanding of the IMF submission is that each Mission has a different focus. This year, I understand the Mission was looking at the question of funding the future cost of New Zealand Superannuation and therefore the tax policies required. This led the Mission to call for some tax policy reforms

“Tax policy can support a more growth-friendly fiscal consolidation, and reforms aimed at improving the tax mix can help increase the efficiency of the income tax system while reducing the cost of capital to incentivize investment and foster productivity growth. Options include a comprehensive capital gains tax, a land value tax, and judicious adjustments to the corporate income tax regime.”

I expect we’ll hear a lot more about this when we see the final report.

“Initiate early dialogue”

It’s not the first time the IMF have suggested a comprehensive capital gains tax, and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has also frequently made a similar suggestion. Generally speaking, the government of the day just responds, “Yeah, but, nah”. However, the issues prompting the suggestion still don’t go away. In this particular case, the IMF suggests we need to start transitioning into a new system to cope with the rising cost of New Zealand superannuation.

“It is essential to initiate early dialogue among all stakeholders regarding comprehensive reform options that can help mitigate these challenges and other long term spending pressures from healthcare and aged care care needs with a fair burden sharing across generations. This can be further supported by KiwiSaver reforms aimed at achieving greater private savings retirement savings.”

The IMF is echoing comments myself and others have repeatedly made. We have rising costs in relation to aged healthcare and superannuation and we need to start thinking seriously about how we’re going to address those. This is a multi-generational impact. One of the unusual points about New Zealand Superannuation is it is a fully funded universal pay as you go system.

An intergenerational issue

In other words, it’s available to everyone, but it’s funded out of current taxation. I think there’s a widespread perception that some part of your tax pays for your future superannuation. It doesn’t. Tax paid by working people below the age of retirement is used to fund the current superannuation of those who have retired. The funding of superannuation is therefore a major intergenerational issue but one rarely discussed. Hence the IMF’s call to initiate early dialogue. I’ll have more on this when the IMF releases its final report.

In the meantime, whenever the IMF or OECD calls for tax reforms, the Minister of Finance of the day usually responds, sometimes in quite snippy terms. Sir Michael Cullen was wont to do so as did Nicola Willis last year. This year the Finance Minister hasn’t publicly responded to the IMF concluding statement, possibly because her attention was on this week’s Infrastructure Investment Summit in Auckland.

Foreign Investment Fund changes announced

As part of the summit, the Minister of Revenue Simon Watts has announced that there will be changes to the current Foreign Investment Fund, or FIF regime. The Government has very heavily signalled that it would do something in this space, so this is no surprise.

The proposed changes to the FIF rules include the addition of a new method to calculate a person’s taxable FIF income, the revenue account method, in other words taxing capital gains. According to the Minister;

“This will allow new migrants to be taxed on the realisation basis for their FIF interests that are not easily disposable and acquired before they came to New Zealand. For migrants who risk being double taxed due to their continuing citizenship tax obligations, this method can apply to all their FIF interests.”

This last point is of particular interest to United States citizens who face this double taxation issue, and which is turning people away. Furthermore, these changes will apply to migrants who became New Zealand tax residents on or after 1st April 2024.

More detail needed and further changes ahead?

This is a very good move but there’s a bit more detail still required. Does the reference to new residents arriving on or after 1st April 2024 mean those new residents are able to make use of this provision in the current tax year? One of the other key issues is if you do opt to be taxed on the revenue account method, what tax rate would apply? From discussions with Inland Revenue policy officials, they seem to be intending that it should be at the person’s marginal rate. Which for those on the 39% bracket would not be terribly welcome. So that’s a key design point.

The other thing of note is that Mr Watts added the Government will also be looking at how the rules impact New Zealand residents and will have more to say later in 2025. That’s interesting, because for me, the rules are quite a compliance burden in terms of calculations and have huge impact for everyone who has a KiwiSaver with overseas investments.

How to pay for New Zealand Superannuation

As noted above the IMF are looking very closely at the question of the fiscal cost of superannuation and aged healthcare which they suggest mean reforms to the tax system are needed to address those growing costs.

Coincidentally, Assistant Professor Susan St John of Auckland Business School’s Economic Policy Centre Pensions and Intergenerational Equity Hub released a working paper on New Zealand Superannuation as a basic income. This is an interesting proposal, which I know Susan has been working on for some time with the assistance of Treasury modelling.

The idea is that New Zealand Superannuation is changed into a universal basic income and treated as a grant. This allows an effective claw back mechanism to operate through the tax system. The proposal is that this claw back would generate additional revenue to help meet the cost of pensions and aged care.

The paper begins by setting out the background to the issue, the increasing demographic strains that we’re seeing. It notes that Treasury has been raising this issue for some time now, such as in its 2021 Long Term Fiscal Statement, He Tirohanga Mokopuna and speeches last year by Dominic Stephens of Treasury on the fiscal projections and costs.

Demography and migration

One of the interesting points the paper makes is although we face some financial strains ahead, because of our demographics the cost of New Zealand Superannuation will not be as high as what some nations are currently dealing with.

Incidentally, as part of their concluding statement, the IMF made a number of presentations illustrating certain areas they’re examining in more depth. One was the question of demographic pressures of superannuation, and it made the point that migration is not going to be the magic bullet some policymakers seem to think.

What about means testing?

After setting out the background Susan St John discusses the option of using means testing as a means of addressing costs. The paper looks at what happens in Australia and our own experience when New Zealand Superannuation was means tested for a while – right up until Winston Peters and New Zealand First became part of the first MMP Parliament in 1996. One of the conditions of that coalition agreement was the abolition of the New Zealand Superannuation Surcharge.

Australia tests income and assets but it’s highly complex and achieves a fiscal objective of managing the cost. On the other hand, Australia has a much more well developed long running compulsory private saving scheme, which makes what they call the Age Pension (the equivalent of New Zealand Superannuation) more of a backstop. The paper also notes that the private pension savings in Australia are more generously state subsidised than KiwiSaver.

The Australian means testing approach is very comprehensive and frankly a nightmare. The paper notes our surcharge which operated between 1985 and 1998 was highly unpopular, but it did deliver useful savings. In short, surcharges or means testing helps mitigate superannuation costs. But they are unpopular and like the Australian approach complicated to run. Furthermore, they encourage attempts to mitigate their effect.

Making New Zealand Superannuation a universal basic income

Instead, Susan proposes turning New Zealand Superannuation into a basic income, the New Zealand Superannuation Grant (the NZSG). She also suggests equalising the current different rates which currently apply depending on whether a person is in a relationship or living together, so it becomes a universal basic income for those who’ve reached the superannuation age.

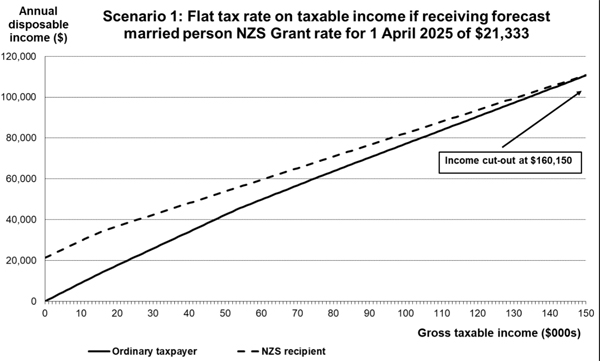

As a basic income the NZSG would no longer be taxable. Instead, when a recipient earns additional income, it’s taxed under a progressive tax regime, so the tax system does the work of providing a claw back of the universal grant for high income people. The effect would be that above a certain point a person decides it’s simply not worth their while taking the NZSG.

For example with a flat tax of 40% on all other income, above $160,150 it would not be worthwhile taking the NZSG.

Another alternative would be a two-tiered rate of 17.5% for the first $15,000 of other income, and 43% on each dollar above. In this case the breakeven point becomes $151,885. A third scenario has a two-tiered rate, 20% for the first $20,000 earned and then 45% above that level. Under this scenario, the income cut out point drops to $135,000. Treasury has helped Susan with the modelling for this paper and its methodology is explained in the appendices to the paper.

15-20% savings possible?

Under Susan’s approach up to 5% of all eligible super annuitants will not apply for the NZSG because there’s no gain in it. She estimates savings could be between $2.8 billion and $3.8 billion or between 15% and 20%.

This is an interesting proposal which seems preferable to reintroducing the New Zealand Superannuation Surcharge or adopting the Australian means testing approach. I think it’s worth considering but the key thing is, as the IMF said, this is an issue we really need to start discussing now because these costs are starting to accelerate as baby boomers age.

It also seems fairer than raising the age of eligibility, which is unfair on Māori and Pasifika. There’s already a seven-year life expectancy gap between Māori and non-Māori so raising the age of eligibility for superannuation is politically difficult particularly as the proportion of the Māori population grows because of those changing demographics.

This is a worthwhile proposal which merits serious consideration as part of the ongoing debate.

This is an edited transcript of the podcast episode recorded on 14th March – it has been edited for clarity and length.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day