This week, more on the Coalition Government’s tax policies and the accelerated restoration of interest deductibility.

- To raise revenue, why not tax marijuana?

- Several Inland Revenue Technical Decision Summaries illustrate the perils of omitting income.

More details have emerged about the Coalition’s tax plans with a surprising twist that changes to interest deductibility for residential property investors have effectively been backdated to 1st April this year. Like many others when I was discussing this last week, I assumed that the reference to 2023/24 was to the Government’s financial year ending 30 June 2024 and the increase to 60% deductibility would kick in from 1st April 2024. (National’s own workings released during the Election use a 30 June year-end).

But this week the ACT Party clarified the increase in deductibility to 60% is in effect for the current income year, ending on 31st March 2024. So effectively, it’s backdated to the start of the year on 1st April. That caused a wee bit of a stir, because something of this nature hasn’t been done in a while. I can’t recall a new government coming in and announcing a tax measure effectively having a retrospective effect.

The change accelerates the restoration of full interest deductibility. It means that from 1st April 2024, interest deductibility will rise to 80% and then will be fully 100% deductible from 1st April 2025. So, within the next 16 or so months, it will be restored to full deductibility. However, as CTU Chief Economist Craig Renney pointed out this acceleration adds another $900 million over the forecast period to the cost of restoring interest deductibility.

Changes to provisional tax?

One of the practical implications of the change is an interesting debate around what action landlords who are provisional taxpayers should take. Such landlords would have paid the first instalment on 28th August. This would have been done based on either 110% of the residual income tax for the 2022 tax year, or 105% of the residual income tax for the 2023 tax year. In both cases, the interest deductibility proportion was higher, so the change might not have an effect. On the other hand, interest rates were lower in both years, particularly in 2022.

What I think you’ll almost certainly see is taxpayers will be keen to understand the impact of the change and how it will affect their provisional tax. My general view would be to pay on 15th January as normal, but then have a really close look before the final instalment on 7th May next year when you should have a fairly good idea of your likely tax liability for the year.

Still there are options to perhaps consider reducing the next amount of provisional tax. And some will take advantage of that. Of course, the risk comes that you may have to pay use of money interest at 10.93%. Although tax pooling can help with that.

What else is now clear?

The release of the Government’s 100 day, 49 point action plan makes clear the Auckland Regional fuel tax is to be abolished and increases to the fuel excise duty will not go ahead. No surprises there as National campaigned on these initiatives. The Clean Car Discount is set to go by the end of this year.

A $900 million bigger hole

As I mentioned earlier, one of the fallouts of the change in the timing of the restoration of full interest deductibility for residential property is an extra blow out by $900 million dollars. One of the apparent means of meeting that gap is the rollback of smokefree legislation, which was set to be world leading. Ironically, several countries seem to have decided to follow our previous example.

The smokefree changes have caused quite a stir. Bernard Hickey in his daily substack The Kaka said that Treasury had estimated that using a 3% discount, smoke free legislation would cut public health costs by $5.25 billion. But that’s now being kicked down the road.

We’ll know more about progress on other measures to fill this gap when the Half Year Economic Fiscal Update, and the promised Mini-Budget are announced on 13th December.

Time to legalise and tax marijuana? The Colorado example.

But if we are looking at the question of raising taxes, or essentially getting more tax revenue from tobacco excise duty, then I’m going to pick up a point that I’ve had for some time and ask why not legalise and tax marijuana. Now, yes, there was a referendum which voted against that. But referendums are not binding on governments. I also think there are second order benefits of legalisation including putting a hole in organised crime’s finances.

At present 24 states in the United States of America have now legalised or decriminalised marijuana. One of those is Colorado, which has a population of just over five million, more or less identical to Aotearoa New Zealand.

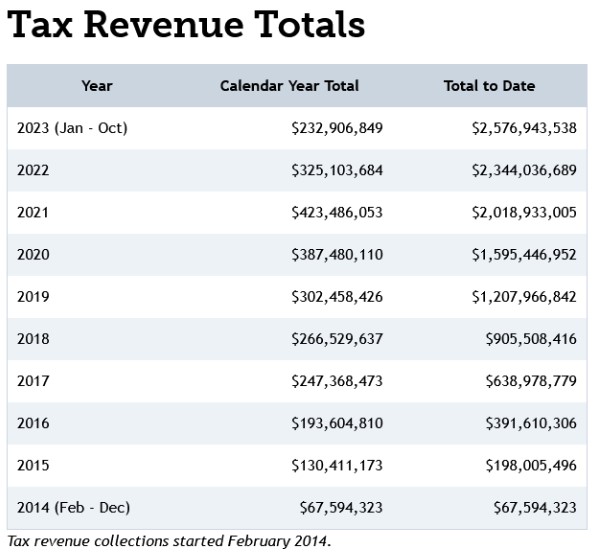

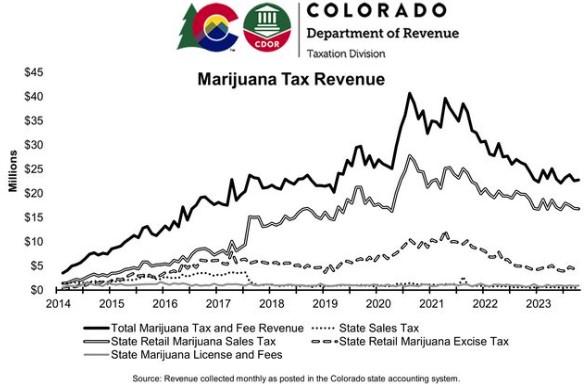

Colorado legalised marijuana in 2014 and have been taxing it since then. The taxes comprise the state sales tax (2.9%) on marijuana sold in stores, the state retail marijuana sales tax (15%) on retail marijuana sold in stores, and the state retail marijuana excise tax (15%) on wholesale sales/transfers of retail marijuana. In addition, Colorado also has fee revenue coming in from licensing and application fees.

Colorado’s Department of Revenue publishes monthly marijuana tax reports, and between February 2014 and October this year it has collected over US$2.5 billion from marijuana taxes. That’s over NZ$4 billion.

However, whether you are taxing smoking or marijuana, long term, the revenue should decline to nil, because ultimately we want people to not smoke because of the health order benefits. You can see this in Colorado’s marijuana tax revenue which rises quite steadily initially but then since mid-2021, it has started to fall away. This is probably the second order effects of people stopping smoking altogether.

But anyway, on average, the tax take is settling down to about US$300 million a year which is roughly $500 million New Zealand dollars. That’s actually a not insubstantial amount of revenue.

So that’s the Colorado example. I’m not going to say it’s going to happen here under the new Government. But you never know. Henry Kissinger died yesterday, and the relevance of that is that he was the one who coined the phrase “Only Nixon could go to China” which opened the door to a US rapprochement with China.

The phrase means bold leadership could surprise people by doing the unexpected. Bear in mind, back in 2015, John Key and Bill English surprised everyone by introducing the bright-line test. The point by referencing Kissinger and Nixon, two of the nastier people of the 20th Century, is that a bold and welcome change of direction can come from an unexpected source.

Revision of the bright-line test – when?

Speaking of the bright-line test, it isn’t specifically mentioned in the 49-point first 100 days action plan the Government announced on Thursday. I imagine we’ll get the timeline for revision at the Half Year Economic Fiscal Update.

“Overlooked” some income? The clock never stops ticking for Inland Revenue

This week Inland Revenue released five Technical Decision Summaries with a common theme relating to disputes over omitted income and penalties. To recap, Technical Decision Summaries are anonymised summaries of adjudication decisions made by a unit within Inland Revenue’s Tax Counsel Office as part of the formal dispute process between Inland Revenue and taxpayers.

The facts vary slightly in each summary, but all involve some form of income diversion/suppression which was picked up by an Inland Revenue review. For example in TDS 23/18 the taxpayer was the sole director and shareholder of Company B which carried on a retail business. The taxpayer also held 49% of the shares in Company A which operated a retail business. Y, who was married to the taxpayer, was Company A’s sole director and held the remaining 51% of its shares. The Taxpayer was also a settlor, trustee, and beneficiary of a Trust which was involved in property investment. (This is a fairly common structure in my experience.)

The Taxpayer filed income tax returns showing wages from which PAYE had been deducted and shareholder salary from Company B and income from the Trust. But on review by Inland Revenue, it appeared that money from Company B had been deposited into the taxpayer and his wife’s personal accounts partner and then used to pay personal expenses and to fund a property major purchase made by another company. These deposits had not been declared as income.

Inland Revenue proposed taxing this income and included a shortfall penalty for tax evasion. The shortfall penalty for tax evasion is 150% of the tax that’s been evaded, although in this case it will be reduced by 50% because of previous good behaviour.

What is also of note here and the other four Technical Decision Summaries is that the four-year time bar period for many tax returns had passed in respect to some of the years in dispute. (Generally, Inland Revenue can’t increase an assessment if it’s more than four years after the end of the tax year in which the relevant return was filed). The taxpayers tried to rely on the time bar rule but Inland Revenue argued it did not apply because of tax evasion and omission of income.

And that is how it panned out. The Tax Counsel Office’s Adjudication Unit ruled there is assessable income and the time bar provision is not applicable because of tax evasion and/or omission of income. Accordingly, the shortfall penalties also applied.

As I mentioned the other Technical Decisions Summaries involved similar issues and had similar outcomes. In TDS 23/16, there was a further problem for the taxpayer in that they were trying to make a subvention payment, to offset losses. And that was also turned down because of a lack of common shareholding.

There are some good lessons from these summaries, primarily if you don’t declare income, don’t try and rely on the time bar to stop Inland Revenue looking at earlier years. As the summaries make apparent it’s very clear Inland Revenue has the power under sections 108 and 108A of the Tax Administration Act 1994 to assess older years that would normally be time barred. In such circumstances, shortfall penalties for tax evasion will almost always apply.

“A really good idea”

As I mentioned last week one of the things that was surprising about the Coalition’s tax policies is the additional resources for Inland Revenue’s audit and investigation activities. On TVNZ’s Q+A last Sunday Minister of Finance Nicola Willis said that she welcomed the proposal which she thought “was a really good idea.”

We’ll only know exactly how much extra funding Inland Revenue is going to get in the Budget next May. But for the moment, you can expect Inland Revenue to be cranking up its investigation activity, and you can expect to see a lot more shortfall penalties kicking in.

And on that note, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.