In her first pre-Budget speech the Finance Minister Nicola Willis confirms tax threshold adjustments will be part of this year’s Budget.

- Meantime the OECD calls for a capital gains tax.

- And I reflect on 40 years in tax – what’s changed or not changed.

The Finance Minister Nicola Willis made the first of what is going to be a series of pre-Budget speeches to the Hutt Valley Chamber of Commerce, and in it she dropped a few clues as to the likely contents of the Budget.

In particular, she announced that the Budget’s “tax relief package will increase the take home pay of 83% of New Zealanders over the age of 15 and 94% of households.”

In case you’re wondering who is in the unlucky 17%, these are taxpayers with annual income currently below $14,000 or with no income at all. They therefore would not benefit from any increase in tax thresholds. According to Inland Revenue in the year to March 2022, there were over 800,000 taxpayers whose income is been between $1.00 and $14,000. There were another 210,000 or so who had no income at all during the 2022 tax year.

14 long years?

In her speech Nicola Willis noted that New Zealanders have not seen any changes to personal income tax rates and thresholds for 14 years. “Unlike most developed countries, New Zealand has made no adjustments to tax brackets to compensate for rampant inflation.” However, having highlighted this point, there wasn’t a commitment in her speech to regular indexation of thresholds, which is how we got 14 years without changes. I’ll have more commentary on that a little later.

The Finance Minister talked about “tax relief aimed at middle and lower-income workers” which is interesting because it hints that maybe threshold adjustments might be focused most on those earning below $70,000. The threshold which I think is most problematic, and Geof Nightingale, Sir Rob McLeod and Robin Oliver all agreed with this, is at $48,000 where the tax rate goes from 17.5% to 30%. There doesn’t appear to be any plans to adjust the tax rates there, but whether there is a bigger proportional increase around that threshold relative to the other thresholds, we’ll have to wait and see. We know by the way that the $180,0000 threshold at which the 39% tax rate kicks in is not likely to be increased.

The OECD joins the call for a capital gains tax

The Finance Minister’s speech came hot on the heels of the latest Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Economic Survey on New Zealand, released on Monday. The big headline here from a tax perspective that the OECD joined the IMF in recommending a capital gains tax. What was interesting here is that when the IMF made this suggestion, Nicola Willis, dismissed it with a snippy comment following in the footsteps of her predecessor Sir Michael Cullen. This time around, there was no such snippy dismissal.

The report actually is quite sobering reading, not just around the tax side of it, but just generally about what it has to say about certain aspects of the New Zealand economy. Education was specifically mentioned as a point where attention needs to be focused on improving standards and therefore flowing through to greater productivity across the economy.

The OECD agreed with the Government’s proposed fiscal approach trying to squeeze spending and keep it under control. It had some criticisms about how budget operating allowances have been allowed to increase in recent years without any real explanation.

The OECD supports the broad-base, low rate approach, a capital gains tax, and tax reliefs for pension saving

But it also made the point that “any tax cuts should be fully funded by offsetting revenue or expenditure measures”, before going on to add “raising revenues should first be achieved through broadening the tax base and reducing distortions before raising rates of existing taxes.” That very much endorses the broad-base, low-rate approach Sir Rob MacLeod in particular espoused in a recent podcast.

No surprises there, but the report continues:

“There is a need to reduce distortions to household choice of asset allocation. Shares, land and owner-occupied residential property are tax favoured. Most capital gains from shares, owner-occupied residential property and land are not taxed. To ensure the tax system is not overly distorting, saving and supporting broader growth, capital gains taxation reform should be done as part of a wider review of tax settings for saving. New Zealand’s tax settings remain an outlier in some respects in international comparison, and notably in offering no tax deduction for contributions and in taxing the returns pensions funds earned while they’re invested and prior to withdrawal at progressive rates, this likely distorts saving away from private pension saving.”

Robin Oliver made the point about over-investment in housing, but as mentioned last week Dr Andrew Coleman picked up on how our taxations of savings is unusual by world standards,

There’s a lot to digest in this 150-page report which is only available online. It’s probably no surprise that expanding the capital gains tax base is not likely to be very high on the agenda of the Coalition Government at the moment. But there’s plenty of food for thought in the report.

One of the other points of interest, and there has been some commentary about this, is the suggestion for an Independent Fiscal Institution, basically, a policy costing unit. The OECD picked up that there had been no independent costings of policies in the run up to last year’s election. This is something that could be done by an Independent Fiscal Institution. Some work was done on this under the last government and Nicola Willis seems open to revisiting the issue.

Following the Irish example?

The OECD survey suggested the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC) https://www.fiscalcouncil.ie/as a model that could could be followed. Given Ireland has a similar population this seems a good idea. Personally, I think we ought to look very closely at countries of comparable size to ourselves. The IFAC has been mandated to independently assess the government’s fiscal stance and budgetary forecasts and monitor compliance with budgetary rules. As I mentioned earlier the OECD thinks that we need to review our budget rules.

According to the OECD survey about 80% of OECD have some form of Independent Fiscal Institution. The Congressional Budget Office in the United States which has 270 staff is a very well-known example. Over in Australia, the Parliamentary Budget Office, with 45 staff has this role. The Canadians have a similar Parliamentary Budget Office and over in the UK they have the Office for Budget Responsibility. There’s plenty of examples around the world to consider and it would be encouraging if we heard something in the Budget about this.

Small businesses and statistics

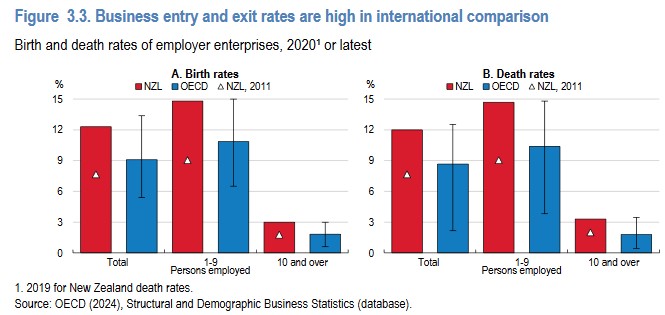

The OECD survey, noted that the business entry and exit rates are higher in international comparison although this means “business dynamism is vibrant” the OECE also noted that the “high share of the population working in micro, small and medium enterprises…hints at a difficulty for these firms to grow into larger businesses.”

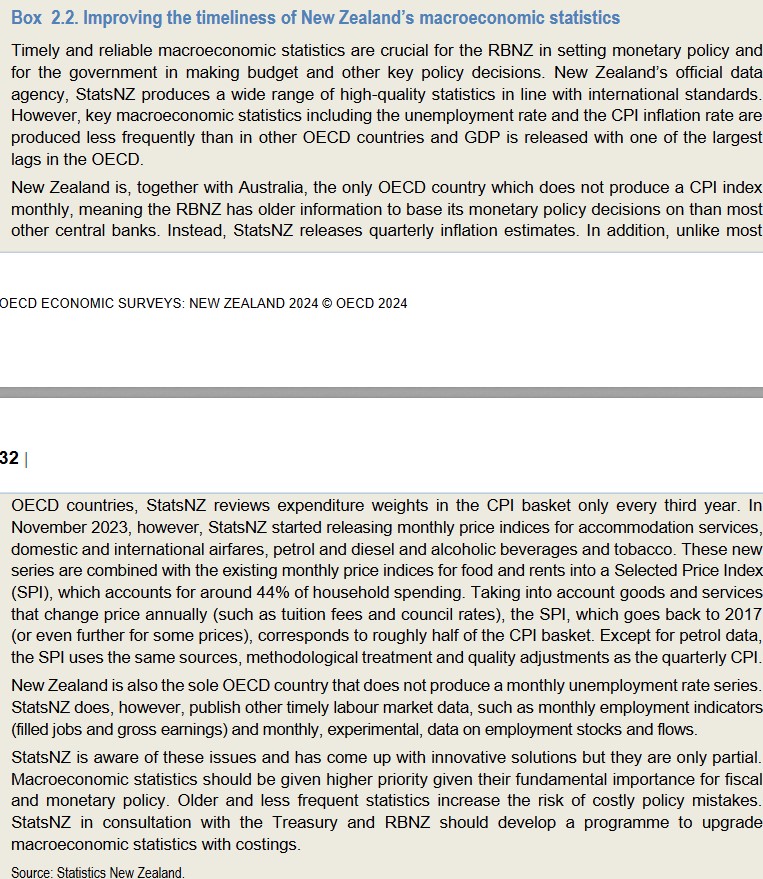

One other thing I thought was very interesting was commentary around improving the timeliness of New Zealand’s macroeconomic statistics. I’ve long thought it was a weakness that we don’t see monthly GDP or inflation data, but I wasn’t aware we were, like Australia, very much in the minority within the OECD in not producing a monthly CPI index. As the OECD noted “Older and less frequent statistics increase the risk of costly policy mistakes”. I wonder what the OECD would have made of the news that all Stats NZ staff were offered voluntary redundancy?

Don’t look back in anger? Forty years in tax

This week, it is 40 years since I started working in tax. They say the past is a different country, we did things differently there and that’s true, but one thing that hasn’t changed over my time in the past 40 years is the behavioural impact of tax. When I started working in the UK, the top rate of income tax was 60% and I saw people very incentivised to make sure that they’re claiming all the possible deductions, maximising pension deductions and the like. The top rate in the UK now is 45%, but you still see the same behavioural impact.

For comparison in 1984 the top rate in New Zealand was officially 60% but a further 10% surcharge had been introduced in 1982 by Sir Robert Muldoon, the Prime Minister and Finance Minister at the time. The top rate was therefore 66% which applied to income above $64,000. Based on CPI since then that’s the equivalent of roughly $260,000 now. According to the Inland Revenue date for the March 2022 income year, just over 42,400 taxpayers earned more than $260,000. That’s a little bit under 1% of all taxpayers. But they had a substantial amount of income between them, close to $20 billion and therefore paid a sizeable amount of tax nearly $7 billion in total.

The effects of forty years of inflation – how New Zealand taxpayers appear to have lost out compared to their UK counterparts

In terms of inflation, it’s quite interesting to look back at the tax rates and the income bands which applied. In 1984 the lowest rate was 20% on the first $6,000 of income. That $6,000 in 1984 dollars would now be $24,350 so in terms of inflation adjustments, even when we see the current 10.5% tax threshold move from $14,000 to maybe $16,000 in the Budget you can see that maybe New Zealanders have been losing out. Consequently, because we aren’t adjusting thresholds regularly, fiscal drag means that inflation has affected the ordinary working New Zealanders quite substantially.

That becomes clearer when you swap notes with what’s gone on in the UK with the tax thresholds there over the same period. The UK has a tax-free personal allowance which Was £2,005 back in 1984 when I started working. It’s now £12,570, but if it had just kept in place in place with inflation, it would be only £6,300. In other words, the value of the tax-free personal allowance has doubled in the past 40 years.

Interestingly, the tax threshold after which the higher tax rates kick in was £15,400 back in 1984. Inflation adjusted that would £48,300 compared with the £50,000 where it actually takes effect. There is an additional rate of 45% in the UK on income over £100,000. Back in 1984 the highest 60% tax rate kicked in at £38,100 inflation adjusted that would be £120,000 now.

What you see looking at these numbers is broadly speaking average earners in the UK have been less affected by fiscal drag and inflation than New Zealand workers have been. And that is something that I think I’d like to see changed here for the better and we should be having regular inflationary adjustments as is required by the UK tax law. I think such a move would tie into the better fiscal discipline suggested by the OECD.

The behavioural impact of no capital gains tax

I’ve now worked for over 30 years in New Zealand, but I still remember my shock when I realised there wasn’t a general capital gains tax here. When I consider the behavioural impact of taxation, that’s where you see it apply most where people will be looking to turn something that could be taxable at 39% into a non-taxable gain. And so, there’s a distortionary effect there.

And just to circle back to discussions we’ve had previously on the podcast and what the OECD have just said, there is a tremendous amount of value in the broad-based low-rate approach. It’s not perfect, but one of the things it does deal with is this question of behavioural impact and distorting behaviour chasing tax benefits. My personal view is the absence of a general capital gains tax has had an effect on our productivity. If it’s better in investment returns to invest in residential property in which the returns are largely tax free, than investing in a business or in shares that are taxed, such as overseas shares under the Foreign Investment Fund regime, then that diverts investment into less productive assets. Whether that’s for the benefit of the wider economy as a whole, well, that is a matter for ongoing debate. My view is it’s not.

And on that note, that’s all for this week, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, kia pai to rā. Have a great day.