- Will the IRD be able to deliver the cost-of-living payment?

- Potentially unwelcome GST surprise for farmers selling up.

- The latest developments from the OECD

Transcript

In the wake of the Budget, a Cost of Living Payments bill was introduced and has now been enacted. As part of the enactment a supplementary analysis report was released giving background to the proposed $350 payment. And this supplementary analysis has some very interesting commentary.

It appears the Cost of Living Payment was put together very much at the last minute as a response to the adverse effects of inflation on low to middle income households. According to these documents, this report was finalised on May 4th, barely two weeks before the Budget was delivered, which is very late in budget terms.

According to the document, Inland Revenue recommended against being the delivery agency for this Cost of Living Payment. The reason it gave was that it was concerned, that being asked to administer the payment would significantly impact its services to customers – taxpayers in plain English.

“The addition of this payment to their portfolio of services Inland Revenue already delivers will compromise Inland Revenue’s already stretched workforce and affect the taxpayer population, including the families and individuals that the payment would be intended to support them.”

Inland Revenue correctly identified that as soon as the announcement was made, they would get contacted about it which would put strains on their systems. It calculated a maximum of approximately 750 full time equivalent staff would be required to handle the payments to be made in the weeks of 1st August, 1st September and 1st October. Now, to put that in context, Inland Revenue staff as of 30th June 2021 was 4,200 full time equivalents. It would therefore need to use the equivalent of 18% of its staff to handle the delivery of this Cost of Living Payment. Quite clearly this would put strains on its system. The $816 million appropriation for the Cost of Living Payments includes $16 million to Inland Revenue for delivery of the services.

It’s therefore likely that Inland Revenue will need to hire additional staff, presumably contractors, on a short-term basis. And as we’ve discussed previously, the issue of contractors hit the courts with the Employment Court ruling that the contractors were not employed by Inland Revenue although I understand that decision is being appealed.

It also seems the Inland Revenue poured a bit of cold water on how the payments would be structured. According to the report, 55% of the total payments to be made will be to the middle 40% of households, 20% would be made to the bottom 30%, and 25% would go to the top 30%. There would be an estimated 478,000 households with children and 610,000 households without children who would receive a Cost of Living Payment. Although around 60% of all potentially eligible recipients will have annual income below $70,000, 10% would have family income of between $70 and $100,000 and 30% will have family incomes over $100,000.

And this led Inland Revenue to point out that potential equity concerns could arise because using individual income to calculate the eligibility for the payment rather than household income may result in different outcomes for households with the same income level. For example, a single person earning $100,000 won’t receive a payment, but a household with two people working who each have income of $50,000 would both receive the payments.

There’s also some analysis regarding how the eligibility is dependent on a person’s prior year’s income, which means the tax returns for the March 2022 must be filed. The paper notes that by the time Inland Revenue begins making payments on 1st August, it expects to have already raised individual tax assessments for approximately 3.2 million individuals, about 75% of individual taxpayers. But that leaves about 500,000 individuals, who may not initially receive the payment between the August to October payment run period because they haven’t filed their tax return. And this includes people who file through tax agents and have in theory until 31st March 2023 to file last year’s tax return.

This underlines a point I made in last week’s Budget commentary that you can probably expect tax agents to come under more pressure to get tax returns done on time so that those people who think they’re eligible may get a Cost of Living Payment. Overall, it’s some interesting insights into the administration of these systems and the Budget process.

GST pitfalls for the unwary

Now moving on, GST is probably the best example you can find of the broad-base low-rate approach to taxation policy. But even though it’s a highly comprehensive tax, that does not make it a simple tax. In fact, it’s full of pitfalls for the unwary. And I’ve been alerted to one which may affect farmers who are selling up.

Back in 2020, Inland Revenue caused some consternation when it issued Interpretation Statement IS20/05 on the supplies of residences and other real property. The Interpretation Statement reversed a long-established policy since 1996 on the sale of the farmhouse where the farmer might have used part of the property for their taxable activity, for example a home office in the homestead. Previously Inland Revenue’s position was that the sale of a farmhouse would generally be a supply of a private or exempt asset and not subject to GST.

However, in IS 20/05, Inland Revenue reversed that position and now said that the sale of the dwelling would have been useful for families who would now be subject to GST. The example the Interpretation Statement gave was if a GST registered farmer was claiming an automatic 20% deduction for farmhouse expenses, an Inland Revenue would expect that the property was therefore being used 20% of the time in the taxable activity and consequently sale of the farmhouse would be a supply in the course or furtherance of a taxable activity and therefore subject to GST.

This change has caused some consternation although some relief was given in the recently enacted Taxation Annual Rates for 2021-2022, GST, and Remedial Matters Act. This included a provision which allowed a deduction for the private use portion of a sale. Coming back to that 20% example I mentioned a moment ago, if 20% of the homestead was used for farming business and 80% for private purposes, there would be an adjustment for the output tax of 80% of the private portion. But that would still mean that 20% of the current value of the farmhouse at the time of sale would be subject to GST, which would be an increased tax burden for many farmers and undoubtedly a surprise for some.

Apparently Inland Revenue is now indicating that it may reconsider its position in its Interpretation Statement, which is a classic example of the military maxim “Order, counter-order, disorder”. But until that point is clarified, farmers who are selling their farm should be aware of this potential liability and seek advice on that transaction.

How the OECD influences our tax policy

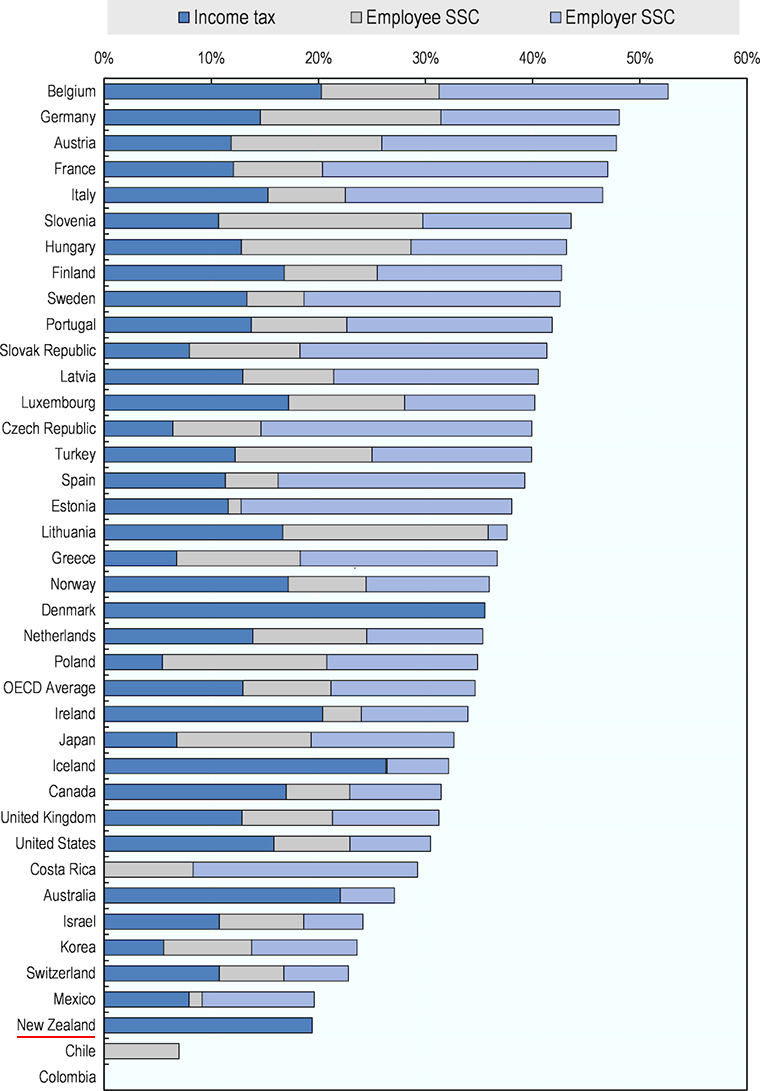

And finally this week, a couple of updates from the OECD. Firstly, it released its annual report on the taxation of wages. This includes its tax wedge analysis, which looks at the difference between labour costs to the employer and the corresponding net take home pay for the employee. Basically, the tax wedge is the sum of the personal tax income tax payable by the employee plus any employee and employer social security contributions plus any payroll taxes less any benefits received by an employee. (I think ACC is included for these purposes).

As can be seen New Zealand, scores very highly with a tax wedge of 19.4%, which is the third lowest in the OECD. The average in the OECD is 34.6%.

What this tax wedge measure also points to is the significance of Social Security and payroll taxes in other jurisdictions. One of the criticisms of the Government’s proposed social insurance scheme is it would be the first real Social Security tax that New Zealand has. It seems from early feedback this is one reason employers are pretty reluctant about the scheme. But even if the scheme was introduced, we’d still be down the lower end of the tax wedge.

Now the second OECD report was titled Tax Cooperation for the 21st Century. This was prepared by the OECD for the G7 finance ministers and central bank governors when they met recently in Germany. It’s particularly interesting because it picks up on what’s been happening with the adoption of the Two Pillar solution for international taxation we’ve talked about recently.

The OECD was asked to prepare was a report that would focus on the further strengthening of international tax co-operation and what recommendations it has in this field. This is looking beyond the implementation of the Two Pillar solution which makes it very significant, in my view, about the future administration of international tax.

For example, a key recommendation is tax administration should be seen as a common mission by tax authorities rather than a potentially adversarial exercise. The development of international cooperation is one of the biggest themes in international taxation in the 21st Century and is also probably one of the least understood. And I will repeat what I’ve said beforehand, most people are oblivious to the amount of information that is being shared by tax authorities at all levels. China, incidentally, has just signed up to the mutual agreement and protocols on that. So every major jurisdiction in the world is cooperating or looking to cooperate on international tax at some level. This is why this paper is important because it starts to map out and where that international co-operation might be going.

The report focuses initially on corporate tax saying there needs to be a reliable framework for cross-border investment. As just noted, tax administration should be seen as a common mission. There should be a collaborative approach with early and binding resolution.

The impact of going digital is emphasised and that it needs to speed up to improve engagement with taxpayers. There are also recommendations beyond corporate tax about moving to real time data availability for taxpayers and tax administrations to make efficient use of evolving technologies while maintaining data privacy and confidentiality.

The issue of data privacy and confidentiality is a developing area where taxpayers are starting to push back against tax authorities because they are concerned, rightly, whether everything is secure as it should be. Furthermore, some are, understandably, not too happy about information sharing.

Finally there’s a recommendation that advanced economies should commit to supporting developing economies so that they can fully benefit from the policy changes. This means building capacity which is going to be needed, especially for the implementation of the Two Pillar solution. Overall, this is a relatively brief but fascinating paper with potentially significant implications.

And just incidentally, on the international Two Pillar solution, the Secretary General of the OECD has now indicated that he expects that implementation will be delayed by a year until 2024. That doesn’t surprise me, given the scale of the project, because there’s a lot of legislation that needs to be put in place by the middle of next year at the latest. Inland Revenue have only just started consultation on the matter.

Still, the Two Pillar project has moved on quicker than some cynics might have expected. But as I’ve said previously, politics is likely to get in the way, particularly the upcoming US Congressional midterm elections. Anyway, as always, we shall bring you the news as it develops.

Well, that’s all for this week I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!