14 Mar, 2019 | Tax News

SkyCity’s moves to set up an offshore online gambling subsidiary throw up a huge range of questions about just how tax should work in the digital age, writes tax consultant Terry Baucher.

The news that SkyCity is voluntarily paying perhaps as much as $40 million in “tax” sounds like someone actually took seriously the remark “Well if you like paying tax so much why don’t you pay extra?”

In fact, what it illustrates is that for a supposedly “simple” tax, GST can get very complex, particularly when it involves services and an offshore entity. So, what’s going on here?

As it says on the tin, GST is a tax on goods and services. It’s pretty easy to work out what’s due and who’s liable when goods are involved. For GST purposes, if the supplier is resident in New Zealand and supplying goods and services to a New Zealand resident, then GST is payable.

Things get more complicated once services are involved, particularly with services delivered online to a New Zealand resident by providers with no physical presence in New Zealand. Resolving the complexities this creates has resulted in a series of amendments to GST as Inland Revenue and the Government try and keep up with the impact of the digital economy. The so-called “Netflix Tax” changes introduced on 1 October 2016 are one such example. As a result, GST is now payable on your Netflix subscription.

Online gambling is just the latest instance of this problem of GST and online services. Betting and gambling are treated as a service for GST purposes and therefore subject to GST. For SkyCity there are big numbers involved: according to its financial statements for the year ended 31st December 2018 it paid just under $100 million in “Gaming GST”.

The world-wide value of online gambling was estimated at US$45 billion in 2017 and this is expected to more than double by 2024.

It’s therefore unsurprising that SkyCity have decided to enter this market. It simply can’t afford not to do so. But since online gambling in New Zealand is at present illegal, SkyCity has to use an offshore subsidiary apparently based in Europe. This subsidiary is therefore a non-resident for GST purposes.

The GST headache for SkyCity is whether its offshore subsidiary must pay GST on the value of the gambling done in New Zealand. (Income tax will only become payable in New Zealand when profits are remitted to New Zealand). If the servers are situated outside New Zealand does that even mean the gambling is happening in New Zealand? Can Sky City’s subsidiary even identify those gamblers if they use VPNs, which can hide a user’s location? And even if it can identify those gamblers located in New Zealand, there remains the most interesting ethical question of all: should SkyCity’s online betting subsidiary pay GST on an activity which is at present essentially illegal in New Zealand?

Surprisingly, the answer to that last question isn’t as clear cut as you might expect, but the short answer is “Yes”. (In a perhaps too on the nose precedent, the High Court in England ruled that an illegal bookmaking business represented a taxable trade even though it involved illegality).

For SkyCity these considerations are compounded by the fact that the penalties for getting its GST calculations wrong are significant: an immediate late payment penalty of 5% plus 1% per month thereafter and use of money interest at 8.22% on the late paid GST. In a worst-case scenario, it could even face shortfall penalties of 20% of the GST due if Inland Revenue thought it had either not taken reasonable care or its tax position was unacceptable. Throw in SkyCity’s disclosure requirements as a listed company and overall, it’s not hard to see why the company felt it should adopt the position of voluntarily paying “tax.” What would be interesting to know is what period the suggested voluntary payment covers. Six months? A year?

It’s quite likely the GST issues involved in online gambling will be resolved by some sort of legislative patch. Nevertheless, a bigger tax question remains, one not really addressed by the Tax Working Group. In an increasingly digital economy, does GST, a tax designed for a non-digital economy, really have a long-term future?

This article first published on The Spinoff

25 Feb, 2019 | Tax News

When hearing the lamentations about the purported cost and harshness a capital gains tax (“CGT”) will bring, I think of Paul1. Dying of cancer he applied to his UK pension scheme for an early payment. Paul died before it arrived, but his widow still got to pay the tax on the transfer.

I am reminded of Judy and Wayne, hard-working specialist nurses living in Auckland, who also transferred their UK National Health Service pensions to New Zealand. They too got a tax bill for their troubles even though it would be five years at the earliest before they could withdraw any cash. Judy and Wayne could not even withdraw funds to pay the $50,000 tax bill. So, in order to meet the bill, a pair of highly skilled nurses in a sector and city with chronic shortages, sold up and moved to the South Island. A real triumph of tax policy.

Nothing the TWG proposes in its final report will be anywhere near as penal as the present rules for taxing foreign superannuation schemes. Or, for that matter, the financial arrangements and foreign investment fund (“FIF”) regimes that will also remain in place. Amidst some of the frankly hysterical reaction these important details have been overlooked.

Listen to Terry discussing the TWG report with Jenée Tibshraeny journalist at Interest.co.nz

The TWG proposes extending the range of assets that will be specifically taxable on disposal. It’s therefore not a CGT in the sense of a specific part of the Income Tax Act covering all capital transactions. Rather it is, to borrow a phrase, a backstop, applicable if the transaction isn’t taxed elsewhere.

I do not read too much into the minority report by three of the TWG members. It is unusual but should not be a surprise: tax experts by their very nature are an argumentative bunch at the best of times and are as divided over the issue as the general public. What is interesting about the minority view is that all three, including long-time CGT sceptic Robin Oliver, support taxing disposals of residential property.

That, together with comments in the report that the Government doesn’t have to accept all the TWG’s proposals about extending the taxation of capital, opens the door for a partial extension only on residential property investment.

The issue will dominate politics between now and next year’s election and the Government will need to decide quickly if the relevant legislation is to be in place before the proposed start date of 1 April 2021. In this context, Inland Revenue’s capability to deliver will be tested, which prompted Michael Cullen to remark that it might need support from countries that have CGT regimes to help get the legislation ready. He and the report also stressed the need of ensuring Inland Revenue is properly resourced and keeps its most skilled staff, which according to Cullen isn’t happening at the moment.

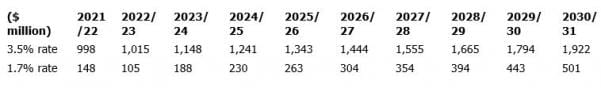

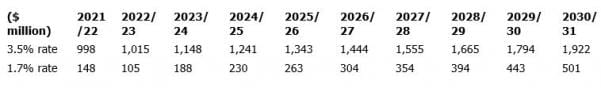

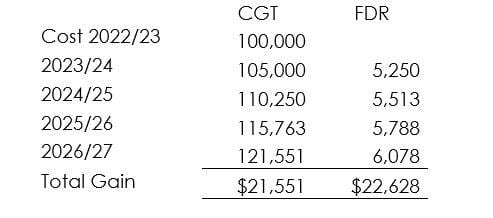

Although a CGT is the preferred option, the TWG report does consider the use of a deemed return method similar to the fair dividend rate applicable under the FIF regime. Table 5.1 of the report suggests that the deemed return method could immediately raise more tax than adopting the CGT approach depending on the deemed rate of return applied:

Deemed Return Rate for CGT

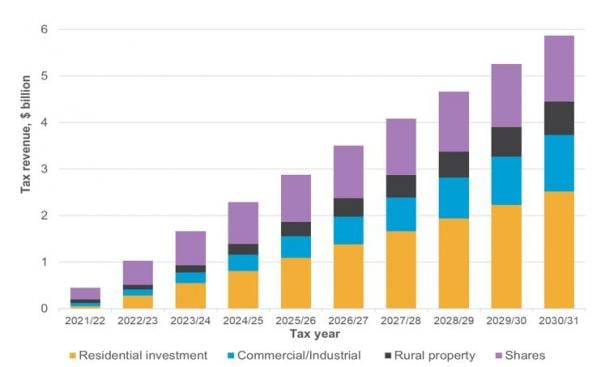

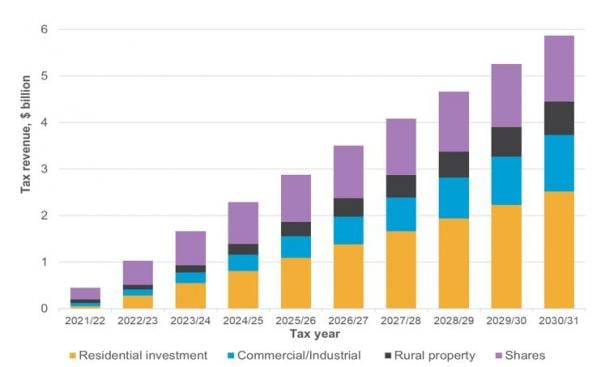

According to the TWG, the projected revenue from a CGT over the first ten years rises from $400 million in the first year to $5.9 billion by 2030/31.

Future Tax Revenues estimate from Capital Gains TaxT

After ten years CGT would represent 1.2% of GDP and a not insignificant 4.2% of total tax revenue.

That raises an interesting point about how a Government might react if a downturn affected tax receipts from CGT. This was a very real problem for California and New York State in particular in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. The deemed return method’s predictability of tax receipts is one reason why it might still be an option.

As noted above the broadening of the taxation of capital income doesn’t replace existing rules such as the FIF and financial arrangements regimes. With regard to the FIF rules, the TWG recommends that the FDR method should be retained. It does consider the present 5% rate should be able to be adjusted frequently as economic conditions change. However, the TWG considers the current ability for individuals and trusts to adopt the alternative comparative value (CV) method if it is lower than FDR as;

“anomalous and inconsistent with the idea behind taxing a risk-free return. It also potentially creates a bias in favour of non-Australasian shares because taxpayers are subject to a maximum 5% rate of return but can elect the actual rate of return if it is lower…. If the FDR rate is ultimately lowered from 5%, the Group recommends removing the ability to choose to apply the CV option only in years where shares have returned less than 5%”

Such a move would increase the tax payable by individual investors unless the FDR rate was set at a level which was fiscally neutral. But it highlights the complexity which will still remain if a CGT approach is adopted.

Volume II of the report has the design details of the proposed CGT.

Two areas of the design have provoked a fair amount of commentary, the treatment of inflation and the proposed valuation day approach.

At first sight the criticism regarding the proposal to adjust for inflation seems reasonable. But as the interim report noted the tax system doesn’t adjust for inflation generally at the moment. Furthermore, as Cullen noted at the briefing the amount taxed under a CGT approach is often lower than that payable under an annual accrual-based approach.

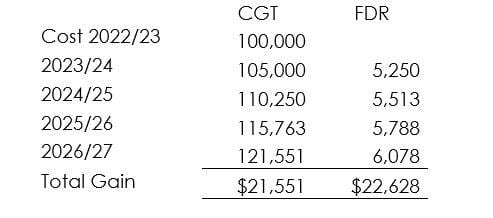

For example, compare the totals taxable between a CGT approach and under the foreign investment fund fair dividend rate method. Assuming $100,000 is invested, which grows at 5% per annum and is sold after four years under CGT, the taxable gain will be $21,551. This is less than the total of $22,628 taxed under the FDR method (generally no income is taxed under FDR in the year of acquisition).

Capital Gains Tax versus Fair Dividend Rate

The TWG proposes that under the CGT approach only gains arising from the date of implementation will be taxed, the so-called “Valuation Day” method which both Canada and South Africa adopted when they introduced their respective CGT regimes.

The potential compliance costs involved have been criticised so the TWG proposes taxpayers should have five years from implementation (or to the time of sale if that is earlier) to determine a value. They also suggest a couple of default methods for assets held on Valuation Day. These are either the straight-line basis or the median method, helpfully illustrated below.

John purchased a small trucking business on 1 April 2015 for $200,000. On 31 March 2025, John sells the business to Paul for $600,000 (i.e. a $400,000 gain).

As a result of the extension of the taxation of capital gains, John will have to pay tax on the capital gain he has derived since Valuation Day (1 April 2021) from the sale of the business (i.e. for the last four years he has owned the business).

Applying a straight-line approach, John will have to pay tax on 4/10th of the gain on sale (i.e. $160,000).

Example business valuation and CGT

The median rule determines the deductible cost as the median or middle value of actual cost (including improvement costs), the value on Valuation Day, plus improvement costs, and the sale price.

In 2014 Scott bought a rental property for $500,000. On Valuation Day the property was valued at $450,000. Scott sold the property six years after Valuation Day for $850,000.

Applying the median rule:

Cost = $500,000

Valuation Day value = $450,000

Sale price = $850,000

The median value is $500,000. Therefore, Scott is able to deduct $500,000 from the sale price of $850,000, giving rise to a $350,000 taxable gain.

Without the median rule, Scott would have a taxable gain of $400,000 (i.e. sale price of $850,000 – price on Valuation Day of $450,000) despite only making a gain of $350,000 over the whole period he owned the property.

There is, as you’d expect, a wealth of detail in these proposals including some anti-avoidance provisions to prevent “bed and breakfasting” as a means of accessing losses. Some losses will be ring-fenced but in general most capital losses should be able to be offset against other income.

There’s plenty more elsewhere to consider in the report such as the proposals for KiwiSaver and the surprising suggestion that the Government “give favourable consideration” to exempting the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from tax. I’ll cover these and other snippets separately.

This post first appeared on Interest.co.nz

18 Feb, 2019 | Tax News

The year ahead in tax will be dominated by this week’s release of the Tax Working Group’s final report. The TWG is expected to recommend the introduction of a realisation based capital gains tax to close a perceived major gap in New Zealand’s tax system.

The coming debate over CGT will almost certainly drown out the majority of the rest of the TWG’s recommendations, and will dominate public discussions about tax this year.

But even without the TWG’s final report, 2019 is going to be a hugely significant year for Inland Revenue and its “customers”. In April the third stage (Release 3) of Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation goes live, the biggest test yet of Inland Revenue’s $1.5 billion programme. (The overall Business Transformation budget for the year ended 30th June is $206.8 million for operating expenditure and a further $91 million in capital expenditure.)

Release 3 implements changes affecting nearly two million taxpayers on PAYE. From 1st April Inland Revenue will automatically calculate the tax position for the year ended 31st March 2019 for all employees on PAYE. Taxpayers will no longer need to apply for a refund either themselves or through one of the tax refund companies. It’s anticipated an estimated 1.67 million taxpayers will receive a refund – about 720,000 for the first time ever. A further 263,000 taxpayers are expected to receive tax demands, about 115,000 for the first time.

Unsurprisingly, the spectre of Novopay hangs over Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation programme, so right now Inland Revenue is racing to make sure everything will be ready in April. However, there are signs it is not wholly on track.

As part of Business Transformation, Inland Revenue prepares monthly reports updating the Minister of Revenue on progress. The latest available report for November 2018 was prepared on 10th December 2018.

It doesn’t take much reading between the lines for it to become apparent there are concerns about whether Inland Revenue will be ready. The update reports

“Whilst our overall status remains at amber over the last reporting period the schedule “key” has deteriorated to amber as a result of the challenges we are experiencing with testing. The resources “key” has deteriorated to amber due to some constraints managing resources between Releases 3 and 4 and the delivery partners “key” has deteriorated to light amber”

An amber status means there are “some” risks to achieving the targeted go live date of 23rd April although Inland Revenue believes it is still on track. Those risks include testing, managing the transfer of data from the tax refund companies, payday filing and tax agents.

The report reveals that Inland Revenue “requested” the 31 tax refund companies (Personal Tax Summary Intermediaries in officialese) to hand over details of some 783,000 clients as part of the preparation for Release 3. 26 of the tax refund companies agreed to do so knowing that Inland Revenue could use its powers under the Tax Administration Act 1994 to compel them to comply. The remaining five companies will have no option but to follow suit. Many of the tax refund companies are expected to close down once Release 3 takes effect.

As another report on the Business Transformation prepared by the Minister of Revenue for the Cabinet Government Administration and Expenditure Review Committee observes, the tax refund companies are amongst a number of groups who are “potentially less positive” about the changes.

Other than the tax refund companies, these groups include the more than 5,600 tax agents responsible for 2.7 million taxpayers, financial institutions and over 200,000 employers. All face significant costs and disruption getting ready for Release 3, particularly in relation to increased reporting requirements.

As I outlined previously Inland Revenue’s relationship with tax agents has been problematic for some time and shows little sign of improving.

Inland Revenue should also be concerned about the slow progress on another key change starting in April payday filing. Under payday filing all employers are required to file salary and wages information with Inland Revenue on the date of payment rather than monthly as at present. Long term, payday filing will benefit employees by providing real-time information to ensure they are not under/overpaid during a tax year. In the short term, however, it represents a significant compliance cost for employers, particularly smaller employers.

At present Inland Revenue’s own online payday filing system could be generously described as “not very user friendly” and other software providers seem to be behind schedule in delivering alternatives. Worryingly, as of 30 November 2018 only 6,500 employers of approximately 207,000 had “indicated” an intention to begin payday filing. These are probably the largest employers covering the majority of New Zealand’s 2.5 million salary and wage earners. It still means a significant number of employers may not be ready by 1 April.

One option to help smaller employers and mitigate their costs could be to extend the existing payroll subsidy. However, this was rejected by Inland Revenue in its report to the Finance and Expenditure Committee on the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2018–19, Modernising Tax Administration, and Remedial Matters) Bill partly because the estimated cost of $8.9 million was unbudgeted.

Imposing additional obligations on employers and simultaneously rejecting a subsidy to help them do so are not reconcilable decisions. In my view it represents a clear breach of Inland Revenue’s duty under section 6A of the Tax Administration Act to take into consideration “the compliance costs incurred by taxpayers”. This important point is barely acknowledged, let alone discussed in either report. Maybe it would be useful if MPs on the Finance and Expenditure Committee spent less time grandstanding and more time monitoring Inland Revenue’s performance and obligations.

Release 3 isn’t the only significant change happening in April. From 1st April residential property investors will lose the ability to offset losses against other income when loss ring-fencing is introduced. According to Inland Revenue about 40% of all residential property investors report rental losses with an average tax benefit of $2,000 per annum. The measure is expected to raise about $190 million in additional tax.

Looking beyond April, the Budget in May will be the first under Treasury’s new Living Standards Framework. It will be interesting to see whether tax changes are included to help meet the proposed focus on wellbeing and the environment. Separately, we may also see some measures implementing some of the less controversial recommendations of the TWG.

So, it will be a very busy year ahead in tax. Although for now, all eyes will be on the TWG’s final report, come April Release 3 will affect many more taxpayers than any hypothetical capital gains tax. Although Inland Revenue expects some teething problems as the changes bed in (it proposes to have additional support or “early life support” for staff and “customers” for some 13 weeks after Release 3), it also expects the initial pain will be replaced by long term benefits. Just don’t talk to tax agents and employers about it.

This article first published on Interest.co.nz