The ramifications from the removal of tax depreciation on all buildings

Tax is full of unintended consequences and one such instance is probably critical to Jenée Tibshraeny’s exposé of the problems many bodies corporate of apartment blocks now face.

The story begins in January 2010 when the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group (the VUW TWG) released its report. The VUW TWG’s key recommendation was for the personal, trust and company income tax rates to be aligned as far as possible. This would involve a reduction in the top personal income tax rate from 38% to 33%. The VUW TWG also commented on the need for the company income tax rate to remain competitive.

The VUW TWG also recommended broadening the tax base “to address some of the existing biases in the tax system and to improve its efficiency and sustainability.” It then noted that base-broadening would be “required if there are to be reductions in corporate and personal tax rates while maintaining tax revenue levels.” The VUW TWG suggested that one such base-broadening measure could be an increase in the rate of GST from 12.5% to 15%. Another measure could be “Removing tax depreciation on buildings (or certain categories of buildings) if empirical evidence shows that they do not depreciate in value.”

The evidence presented to the VUW TWG indicated commercial and industrial properties did in fact depreciate in value. However, this didn’t appear to be the case for residential properties.

Accordingly, the initial costings for the 2010 Budget only proposed the removal of depreciation on residential properties. This would raise approximately $340 million in its first year which would help pay for the proposed income tax cuts. Once it was decided to reduce the company tax rate from 30% to 28% (a measure expected to cost $410 million in its first year), the decision was also taken to remove depreciation from all buildings. This raised a further $345 million towards the personal income and company tax cuts.

The National Government duly adopted the VUW TWG’s tax rate alignment proposals, announcing these in its 2010 Budget released on 20th May. With effect from 1 October 2010 personal income tax rates and thresholds would be adjusted and the present top personal rate of 33% introduced. The rate of GST would increase to 15% with effect from the same date and tax depreciation on all buildings would be removed with effect from the start of the 2011-12 income year (1 April 2011 for most taxpayers).

Then the Canterbury Earthquakes happened.

By 1 April 2011 it was quite apparent that owners of commercial and residential investment properties in Canterbury faced significant repair and/or rebuilding costs. Furthermore, all commercial property owners throughout New Zealand would also need to carry out seismic strengthening at a cost initially estimated to be almost $1.4 billion.

Owners of investment properties also had a big tax problem – was the cost of repair and seismic strengthening work tax deductible? Prior to 1 April 2011 if expenditure wasn’t deductible it could at least be depreciated. Repairs were probably deductible but investors rebuilding properties could no longer claim a depreciation deduction unless they could demonstrate the building’s life would be under 50 years. As for seismic strengthening the tax treatment was unclear – were they a repair and therefore deductible or an improvement and non-deductible?

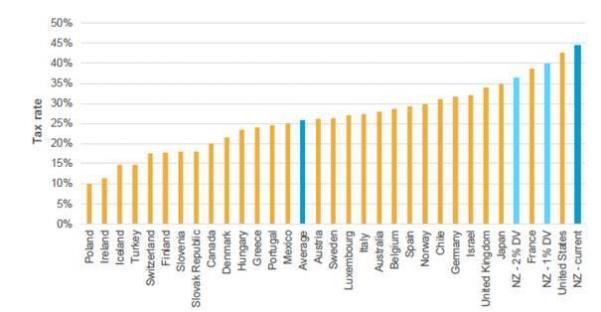

This unsatisfactory state of affairs has continued since then. It caught the attention of the latest Tax Working Group (the Cullen TWG). It noted that the withdrawal of depreciation now meant that by 2015 New Zealand had the highest effective tax rate for foreign investment into both manufacturing plants and office buildings among OECD countries.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG estimated the fiscal costs over five years of these various options as between $70 million (seismic strengthening only) and $1.46 billion (industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings).[1] They were, of course, conditional on the availability of additional revenue from the extension of the taxation of capital gains.

As we know, that isn’t happening but fortunately the treatment of seismic strengthening is one of the Cullen TWG’s recommendations which is a high priority for inclusion in Inland Revenue’s tax work policy programme. Frankly, nearly nine years after the Canterbury Earthquakes first hit, this is a well overdue move.

The Cullen TWG interim report in September 2018 also had some commentary on the effects of the reduction of company tax rates in 2010.

“The two most recent reductions in the company rate in New Zealand – in 2008 and 2011 – were not associated with an increase in foreign investment. In fact, the stock of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP trended down slightly in the following years. There was also no increase in the level of foreign investment relative to Australia, whose company rate was unchanged during that period.”[2]

In short, New Zealand didn’t get much return in the form of foreign direct investment for its cuts in the company tax rate.

There is perhaps one final irony at play here: holders of investment properties were among the fiercest critics of the Cullen Tax Working Group’s recommended capital gains tax. Did they win that battle at the cost of the loss of the reintroduction of building depreciation? If so, may that win turn out to be a Pyrrhic victory?

[1] Table 6.1, Chapter 6

[2] Para 21, Chapter 14

This article first published on Interest.co.nz