22 Aug, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- A big tax break for build-to-rent developers

- The role tax has played in the housing crisis

- Clarifying the treatment of donations to private schools

Transcript

Housing Minister Megan Woods recently made a surprise announcement that blocks of at least 20 new and existing build to rent flats will be exempt from the interest deductibility limitation rules in perpetuity if they offer 10-year tenancies. Currently, build to rent flats would only qualify for the exemption from interest deductibility rules if they are new builds and then only for 20 years.

This is quite a significant change clearly aimed at the developing build to rent market, which after the announcement of interest deductibility limitation was made last year was quite concerned that the sector would be very hard hit by the proposals. During the group discussions and consultation that went on with Inland Revenue in the run up to the release of the relevant legislation, these concerns came across very strongly from the build to rent sector.

Obviously, they’ve continued lobbying in the background and have won this concession. This is a big win for the sector as it will probably greatly shake up the rental market over the long term. It gives it security of supply and therefore for financing. But it’s also a win for tenancy advocates who have been pushing there should be longer tenancies available to renters similar to what we see in continental Europe.

It’s also worth noting that this new exemption will apply to existing properties. Therefore, if you take an existing property and convert them into 20 apartments or flats, then you qualify for this permanent exemption. Again, last year there was quite a bit of discussion over what constituted a “new build” and conversions were high in the list of matters under consideration.

On the other hand, the move does further sideline the mum and dad type investors who are currently a large part of the rental market. And at the moment they will definitely be left hoping for a change of government next year. Overall, this change seems a smart policy to boost the growing rent to build sector, but also give greater protection to tenants.

The reasons for very high house price inflation

Moving on, exactly why house price inflation in New Zealand has been so high has long been a matter of debate. The Multi-Agency Housing Technical Working Group, which consists of members from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Treasury has been studying this issue in some detail.

And on Thursday the Housing Technical Working Group released a report on the housing system based on a close look at the housing development system in Hamilton, Waikato area.

Now the group’s key conclusion was:

“…a combination of a global decline in interest rates, the tax system, and restrictions on the supply of land for urban use have led to a large change in the ratio of prices to rents and are the main cause of higher house prices in Hamilton-Waikato, as well as other parts of Aotearoa New Zealand, over the past 20 years.”

The report has some interesting insights on the road tax matter. The report starts from the pretty standard theory that a neutral tax system is one that treats different economic activities equally. However, the report notes that “New Zealand’s tax system is not neutral” and there are a range of tax distortions that affect house prices, land prices, rents and construction costs.

According to the report, the most important distortions in the tax system are firstly imputed rent, that is the rent owner occupiers effectively pay themselves is not taxed, whereas other forms of income from investments are taxed. This is a very controversial point and conceptually counter-intuitive for owner-occupiers. But it is an approach that the Netherlands has adopted to tax housing on an imputed rental basis.

Secondly, capital gains are often not taxed, whereas other forms of income are. Well, this podcast is a broken record about the distortions the lack of a comprehensive capital gains tax produces.

Then thirdly, the GST is charged as a lump sum when a house is built and is charged on maintenance costs and rates but is not charged on rents. This is a very interesting point and not one that I’d actually considered in much depth.

The consequences of these distortions is the first increases the incentive for people to live in bigger or better houses than otherwise. We see that in New Zealand, new builds are the second or third highest in the world in terms of area.

The report expands on the matter of the first and second distortions, that the lack of capital gains and imputed rent also increases the investment value of housing relative to other investments. This is a well understood point which means those resources devoted to owner occupied housing “yield untaxed shelter in perpetuity as well as untaxed capital gain”. If on the other hand, you put money in the bank or in shares you will be taxed on the income. Finally, as is well known and is one of the reasons for the interest deductibility limitation rules, investing in rental housing yields tax free capital gains for those who hold property long enough.

The report concludes these tax distortions have caused a higher price to rent ratio in New Zealand than under a more neutral tax system. The group also reaches the interesting conclusion that New Zealand is “closer to restricted land supply than abundant and therefore we conclude that these income tax distortions are likely to have driven house prices higher rather than increasing supply and reducing rents.”

The commentary on the impact of GST is interesting because as I said, not many of us have actually thought about that and how it might play out. What it says is that the overall role of GST extends well beyond the “…direct impact on construction costs and includes a complex array of interactions stemming from the fact that GST is not charged on rents but is charged in other goods and that GST is charged only on some land transactions. The report notes “Assessing the overall impact of New Zealand’s GST on house prices is a possible area for future research.”

The report includes an interesting table estimating the impacts of tax distortions on house values for each type of buyer. The report notes the tax distortions were relatively small in 2002 when interest rates were much higher but by 2021, the impact of these tax distortions “had grown significantly”. The report further noted that in a low interest rate environment, the tax distortions were significantly amplified.

Table 2 Impacts of tax distortions on house values for each buyer type

Estimates with current tax settings

(Estimates with ‘neutral’ tax settings) |

| Date

Inflation rate

Interest rate* |

Q2 2002

π = 1.8%

i= 5.6% |

Q2 2011

π = 2.5%

i= 5.4% |

Q2 2016

π = 2.1%

i= 4.1% |

Q2 2021

π = 2.0%

i= 3.5% |

| Landlord

Equity financed |

$169,031

($114,495) |

$289,709

($185,365) |

$438,582

($261,808) |

$680,901

($379,377) |

| Landlord

60% debt** |

$164,869

($112,175) |

$276,188

($179,021) |

$435,601

($261,950) |

$431,979

($400,966) |

| Owner-occupier

Equity financed |

$189,161

($89,753) |

$278,309

($141,369) |

$367,980

($185,213) |

$516,949

($255,797) |

This is a very interesting report which feeds into the ongoing debate about housing. I think it underlines a constant theme of this podcast that we need to change our tax settings, settings around the taxation of capital and in particular, housing. Of course, Professor Susan St John and I would be pointing to the fair economic return methodology as one option for starting to take some of these tax distortions out of the market.

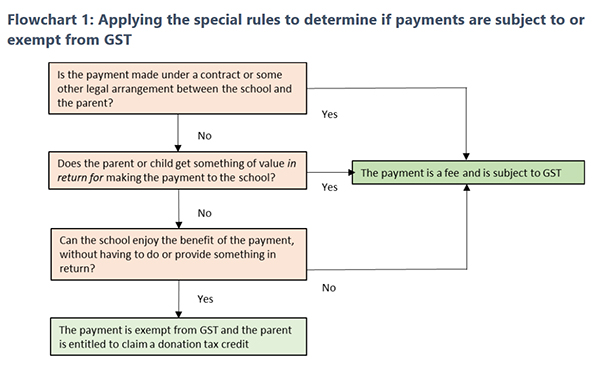

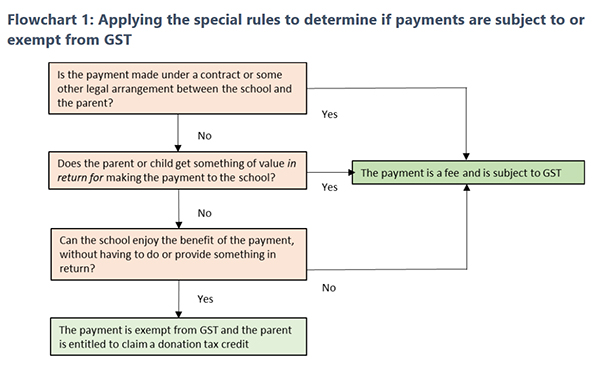

GST and private schools

And finally, private schools have been in the news recently, largely because of the revelations about the behaviour of the newly elected MP for Tauranga. Quite by coincidence, this week Inland Revenue has released a draft Question we’ve been asked on the GST and income tax treatment of payments made by parents to private schools. This also comes with a handy flow fact sheet as well which has a useful flowchart which explains how the rules apply.

Something else to keep in mind are the special rules for calculating GST on school boarding fees. Where students have arranged to board at the school for more than four weeks, the school charges GST at a lower rate (9% or 60% of the standard rate) to the extent the boarding fee is for the supply of domestic goods and services.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

25 Jul, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Depreciating buildings

- Who are taxed the heaviest?

- The OECD says housing should be taxed

Transcript

Inland Revenue has released Interpretation Statement IS 22/04 on claiming depreciation on buildings. Critical to this issue is determining the meaning of a “building” for depreciation purposes and the distinction between residential and non-residential buildings. The Interpretation Statement addresses this issue when it sets out when depreciation may be claimed for non-residential building and also for some fit outs. It confirms that no depreciation is available for residential buildings.

The Interpretation Statement then sets out where you can find the right depreciation rate for buildings when fit outs attached to buildings may be depreciable. How to treat an improvement of a building for depreciation purposes. And then finally, what happens when the building is disposed of or its use changes?

To recap, depreciation for all buildings was reduced to zero, with effect from the 2011-12 income year. Back in 2020 as part of the initial response to the pandemic, the Government reintroduced depreciation for non-residential buildings with effect from the start of the 2020-21 income year. Generally, the depreciation rate is 2% on a diminishing value basis, or 1.5% on a straight-line basis. Some other depreciation rates may be used where the building has a shorter than normal useful economic life. Examples would be barns, portable buildings or hot houses. Additionally, it’s possible to claim a special rate if the building is used in an unusual way.

Now for depreciation purposes “building’ retains its ordinary meaning which means anything that is structural to the building or used for weatherproofing the building. The Interpretation Statement emphasises that whether a building is residential or non-residential is an all or nothing test. If the building is non-residential depreciation is available, otherwise not, there’s no apportionment.

Residential buildings are any places mainly used as a place of residence. This includes garages or sheds included with that building. Places used as residential residences for independent living in retirement villages and rest homes are residential buildings are is short stay accommodation where there’s less than four separate units.

On the other hand, non-residential buildings include buildings used predominantly for commercial and industrial purposes, but not residential buildings. This also includes hotels, motels, inns, boarding houses, serviced apartments and camping grounds. Retirement villages and rest homes where places are not being used for independent living are non-residential buildings as is short stay accommodation where there are four or more separate units.

If improvements are made to a building, you must treat it as a separate item of depreciable property in the first tax year. Then you can either continue to treat it as a separate item of depreciable property or simply add it to the building by increasing the adjusted taxable value of the building.

In some cases, a fit out can be separately depreciated depending on the nature of the building and the nature of the fit out. Where the fit out is considered structural to the building or used to weatherproof the building it must be treated as part of building and not depreciated separately. Fit outs are depreciable in a wholly non-residential building and sometimes in a mixed-use building. But remember, the key point is that depreciation is not available under any circumstances for a residential building. So overall, this is a useful Interpretation Statement and is also, as has become the norm, accompanied by a very handy fact sheet.

The agencies tackling organised crime and its tax evasion

Moving on, last week I discussed a suggestion by ACT Party leader David Seymour to use Inland Revenue against the gangs. I looked at the powers available to Inland Revenue and discussed how practical his proposal was. To summarise, Inland Revenue has extensive powers which would be useful in tackling gangs and organised crime. However, this is a resource intensive approach which probably in Inland Revenue’s view, would divert its attention from other areas it considers equally important.

This prompted some discussion in the comments section and thank you again to all those who contributed. As I said, my view is Inland Revenue probably thinks other agencies, such as the Police, are better suited for this activity. But it will cooperate with those agencies. Its annual reports make clear they pass information to other agencies. So Inland Revenue is probably working on this matter in the background.

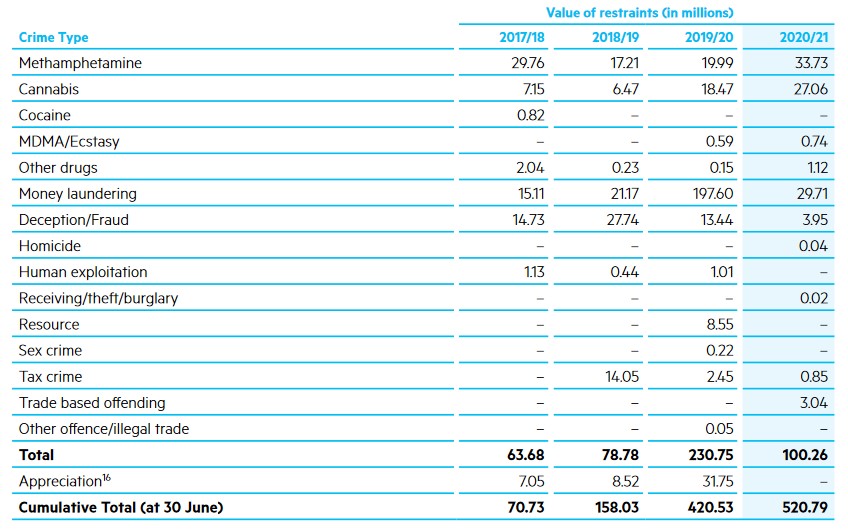

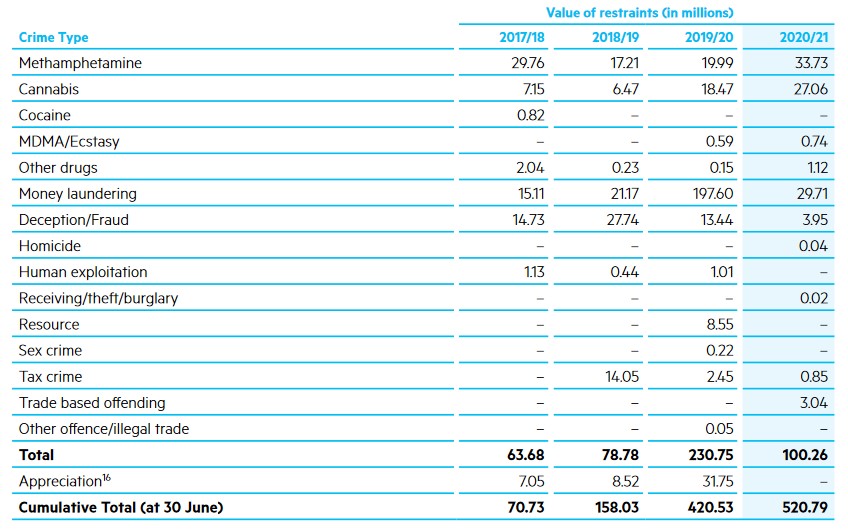

It was interesting just to take a look to see what other agencies were doing in this space and get a gauge of what’s happening. A key tool for the Police is the use of restraining orders to seize assets. According to the Police’s Annual Report for the year ended 30th June 2021 the value of restraints for the year totalled just over $100 million, including nearly $30 million seized from anti-money laundering.

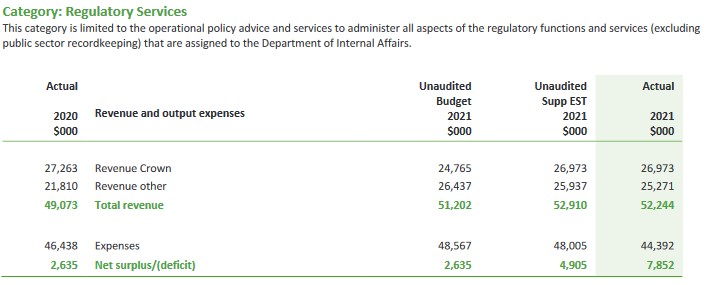

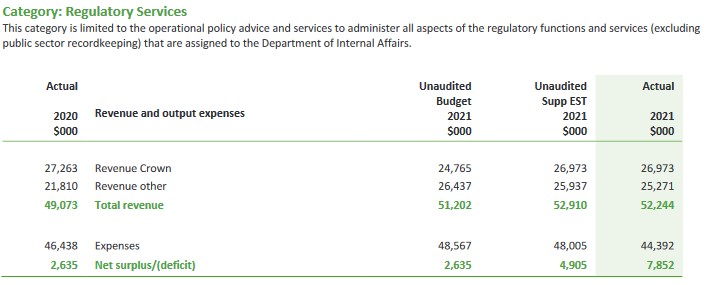

The Department of Internal Affairs also has responsibilities for anti-money laundering, as it’s a key regulator on that. Its Annual Report to June 2021 indicates that perhaps it could do more in this space, as its budget for its regulatory services for the year was set at $52 million, but it only spent $44 million.

And then when you look at the DIA’s performance metrics, such as desk-based reviews of reporting entities, it’s supposed to be targeting between 150 and 350 such reviews annually, but managed only 219 for the year, up from 198 in the previous year. And on-site visits were meant to be somewhere between 70 and 180 but came in at 79. To be fair these were probably disrupted by the impact of COVID 19.

Still, there are other agencies involved in pursuing gangs including Customs who will also be very interested. Inland Revenue will be playing a role, it shares information with these other agencies. So even if it’s not wielding a very big stick publicly, it’s working in the background.

The interaction of tax and abatements on social assistance

Now tax has been in the news a lot recently with the election coming up even though it’s still just over a year away probably. National and the ACT Party have both set out they would proposed some tax cuts. Last Saturday, Max Rashbrooke, a senior associate at the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies, who has written quite a lot on wealth and taxation put out some counter proposals to National and ACT’s proposals.

He suggested that really the focus should be on middle income earners. And he made a suggestion, for example, that we could have a $5,000 income tax free threshold, something we see in other jurisdictions. Britain’s is just over £12,500, Australia’s is A$18,200 and the US has a slightly different thing. It gives you a standard deduction of US$12,000. But anyway, let’s take that comment elsewhere. And Max suggested that something could be done in that space.

But it got me thinking about the question of who does actually pay the highest tax rates in the country. And the answer isn’t those on over $180,000 where the tax rate is 39%, it’s actually more around $50,000 mark if those people are receiving any form of government assistance, such as Working for Families. If they have a student loan as well, then an additional 12% of their salary after tax gets deducted.

The interaction of tax and abatements on social assistance, such as the family tax credit and parental tax credit can mean in some cases, the effective marginal tax rate for some families is more than 100% on every extra dollar they’re earning. This is an issue which the Welfare Expert Advisory Group touched on, but the Tax Working Group wasn’t allowed to address. But it’s a huge problem.

Take, for example, someone earning $50,000, just above the $48,000 threshold where the tax rate goes from 17% to 30%. And that, by the way, is the rate where I think we need to focus our attention on adjustments to thresholds and tax rates. At that level every extra dollar they’re earning is taxed at 30%. If they’ve got a student loan then they pay a further 12%. If they have a young family and are receiving Working for Families tax credits, then these are abated at 27%. Incidentally, the abatement threshold is $42,700. So that means that that person is on a marginal tax rate of 69%. Definitely not nice.

Then there’s a separate credit, the Best Start tax credit which has a separate abatement regime in addition to the Working for Families abatement regime I just explained. So that’s why people could be suffering an effective marginal tax rate of over 100%.

In my view, this is the area where we really need to be thinking about changing the tax system, because to compound matters, governments have been very cynical about not adjusting thresholds for inflation, something I’ve raised repeatedly in the past.

Working for Families thresholds were adjusted for inflation every year until National was elected in 2008. Starting in the 2010 Budget they started freezing thresholds. They also increased the abatement rate which used to be 20% and is now 27%. The current Working for Families abatement threshold is $42,700, which is less than what someone working full time on the minimum wage will earn annually

Looking at student loans the threshold where repayments start in 2009 was $19,084. That is now $21,268 but for a long period of time under the last government it was frozen. National also increased the repayment rate from 10% to 12% in 2013.

So this is an area where governments of both hues have been really quite cynical in my view, and where a lot of serious thought needs to go in about trying to address the inequities that have arisen. The Welfare Expert Advisory Group suggested the abatement rate should be 10% on incomes between $48,000 and $65,000, then increase to 15% before rising to 50% on family incomes over $160,000. (Yes, large families with that level of income could be receiving social assistance in some instances).

There’s a lot of work to be done in this space and inflation adjustments to thresholds is something that should be done anyway. But I think we need to think carefully around the thresholds and how the interaction with social assistance works. At the moment we’re not getting that sort of analysis from either any of the main parties and that’s disappointing, as it’s something that really needs to be addressed.

Why the FER deals with recurrent taxes better

And finally this week, just hot off the press is an OECD report on Housing Taxation in OECD countries. This makes for some interesting reading. Briefly, the report is concerned about how housing wealth is mostly concentrated amongst high income, high-wealth and older households. And in some cases, they believe that a disproportionately large share of owner-occupied housing wealth is held by this group. There’s been unprecedented growth in house prices, not just in New Zealand, but across the whole OECD, making housing market access increasingly difficult for younger generations.

In terms of suggestions the OECD believes that housing taxes are “of growing importance given the pressure on governments to raise revenues, improve the functioning of housing markets and combat inequality.” The report notes the way housing taxes are designed often reduces their efficiency. Recurrent property taxes, such as rates, are often levied on outdated property values, which significantly reduces their revenue potential. This also reduces how equitable they are because where housing prices have rocketed up, people are underpaying based on current values. And conversely people in places where prices are falling or have been stagnant are paying more relative to those in richer areas.

One of the suggestions the report makes is that the role of recurrent taxes on immovable property should be strengthened, by ensuring that they are levied on regularly updated property values. And this is one of these reasons why Professor Susan St John and I have been promoting the Fair Economic Return approach. One of the strongpoints of our proposal would be strengthening the role of recurrent taxes.

Capping a capital gains tax exemption on the sale of a primary residence

Another proposal would not at all popular. It is to consider capping the capital gains tax exemption on the sale of main houses so that the highest value gains are taxed. This should strengthen progressivity in the system and reduce some of the upward pressures. This is what happens the U.S. There is a US$250,000 exemption on the main home per person, and above that the gains are taxed. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t have a similar type exemption here if we want to introduce a capital gains tax. But as I said, that would be particularly unpopular.

The OECD also believes there should be better targeted incentives for energy efficient housing, because housing, according to this report has a significant carbon footprint, maybe 22% of global final energy consumption and 17% of energy related CO2 emissions.

So, there’s a lot to consider in this report, and we come back to it and consider it in more detail. But again, it sort of comes to this point we’ve talked about repeatedly on the podcast, the question of broadening the tax base and the taxation of capital. These issues aren’t going to go away, particularly when you consider, as I mentioned a few minutes ago, how very high effective marginal tax rates are paid by people on modest incomes who may not have any housing. No doubt we’ll be discussing all these issues sometime again in the future.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!