22 Aug, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- A big tax break for build-to-rent developers

- The role tax has played in the housing crisis

- Clarifying the treatment of donations to private schools

Transcript

Housing Minister Megan Woods recently made a surprise announcement that blocks of at least 20 new and existing build to rent flats will be exempt from the interest deductibility limitation rules in perpetuity if they offer 10-year tenancies. Currently, build to rent flats would only qualify for the exemption from interest deductibility rules if they are new builds and then only for 20 years.

This is quite a significant change clearly aimed at the developing build to rent market, which after the announcement of interest deductibility limitation was made last year was quite concerned that the sector would be very hard hit by the proposals. During the group discussions and consultation that went on with Inland Revenue in the run up to the release of the relevant legislation, these concerns came across very strongly from the build to rent sector.

Obviously, they’ve continued lobbying in the background and have won this concession. This is a big win for the sector as it will probably greatly shake up the rental market over the long term. It gives it security of supply and therefore for financing. But it’s also a win for tenancy advocates who have been pushing there should be longer tenancies available to renters similar to what we see in continental Europe.

It’s also worth noting that this new exemption will apply to existing properties. Therefore, if you take an existing property and convert them into 20 apartments or flats, then you qualify for this permanent exemption. Again, last year there was quite a bit of discussion over what constituted a “new build” and conversions were high in the list of matters under consideration.

On the other hand, the move does further sideline the mum and dad type investors who are currently a large part of the rental market. And at the moment they will definitely be left hoping for a change of government next year. Overall, this change seems a smart policy to boost the growing rent to build sector, but also give greater protection to tenants.

The reasons for very high house price inflation

Moving on, exactly why house price inflation in New Zealand has been so high has long been a matter of debate. The Multi-Agency Housing Technical Working Group, which consists of members from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand and the Treasury has been studying this issue in some detail.

And on Thursday the Housing Technical Working Group released a report on the housing system based on a close look at the housing development system in Hamilton, Waikato area.

Now the group’s key conclusion was:

“…a combination of a global decline in interest rates, the tax system, and restrictions on the supply of land for urban use have led to a large change in the ratio of prices to rents and are the main cause of higher house prices in Hamilton-Waikato, as well as other parts of Aotearoa New Zealand, over the past 20 years.”

The report has some interesting insights on the road tax matter. The report starts from the pretty standard theory that a neutral tax system is one that treats different economic activities equally. However, the report notes that “New Zealand’s tax system is not neutral” and there are a range of tax distortions that affect house prices, land prices, rents and construction costs.

According to the report, the most important distortions in the tax system are firstly imputed rent, that is the rent owner occupiers effectively pay themselves is not taxed, whereas other forms of income from investments are taxed. This is a very controversial point and conceptually counter-intuitive for owner-occupiers. But it is an approach that the Netherlands has adopted to tax housing on an imputed rental basis.

Secondly, capital gains are often not taxed, whereas other forms of income are. Well, this podcast is a broken record about the distortions the lack of a comprehensive capital gains tax produces.

Then thirdly, the GST is charged as a lump sum when a house is built and is charged on maintenance costs and rates but is not charged on rents. This is a very interesting point and not one that I’d actually considered in much depth.

The consequences of these distortions is the first increases the incentive for people to live in bigger or better houses than otherwise. We see that in New Zealand, new builds are the second or third highest in the world in terms of area.

The report expands on the matter of the first and second distortions, that the lack of capital gains and imputed rent also increases the investment value of housing relative to other investments. This is a well understood point which means those resources devoted to owner occupied housing “yield untaxed shelter in perpetuity as well as untaxed capital gain”. If on the other hand, you put money in the bank or in shares you will be taxed on the income. Finally, as is well known and is one of the reasons for the interest deductibility limitation rules, investing in rental housing yields tax free capital gains for those who hold property long enough.

The report concludes these tax distortions have caused a higher price to rent ratio in New Zealand than under a more neutral tax system. The group also reaches the interesting conclusion that New Zealand is “closer to restricted land supply than abundant and therefore we conclude that these income tax distortions are likely to have driven house prices higher rather than increasing supply and reducing rents.”

The commentary on the impact of GST is interesting because as I said, not many of us have actually thought about that and how it might play out. What it says is that the overall role of GST extends well beyond the “…direct impact on construction costs and includes a complex array of interactions stemming from the fact that GST is not charged on rents but is charged in other goods and that GST is charged only on some land transactions. The report notes “Assessing the overall impact of New Zealand’s GST on house prices is a possible area for future research.”

The report includes an interesting table estimating the impacts of tax distortions on house values for each type of buyer. The report notes the tax distortions were relatively small in 2002 when interest rates were much higher but by 2021, the impact of these tax distortions “had grown significantly”. The report further noted that in a low interest rate environment, the tax distortions were significantly amplified.

Table 2 Impacts of tax distortions on house values for each buyer type

Estimates with current tax settings

(Estimates with ‘neutral’ tax settings) |

| Date

Inflation rate

Interest rate* |

Q2 2002

π = 1.8%

i= 5.6% |

Q2 2011

π = 2.5%

i= 5.4% |

Q2 2016

π = 2.1%

i= 4.1% |

Q2 2021

π = 2.0%

i= 3.5% |

| Landlord

Equity financed |

$169,031

($114,495) |

$289,709

($185,365) |

$438,582

($261,808) |

$680,901

($379,377) |

| Landlord

60% debt** |

$164,869

($112,175) |

$276,188

($179,021) |

$435,601

($261,950) |

$431,979

($400,966) |

| Owner-occupier

Equity financed |

$189,161

($89,753) |

$278,309

($141,369) |

$367,980

($185,213) |

$516,949

($255,797) |

This is a very interesting report which feeds into the ongoing debate about housing. I think it underlines a constant theme of this podcast that we need to change our tax settings, settings around the taxation of capital and in particular, housing. Of course, Professor Susan St John and I would be pointing to the fair economic return methodology as one option for starting to take some of these tax distortions out of the market.

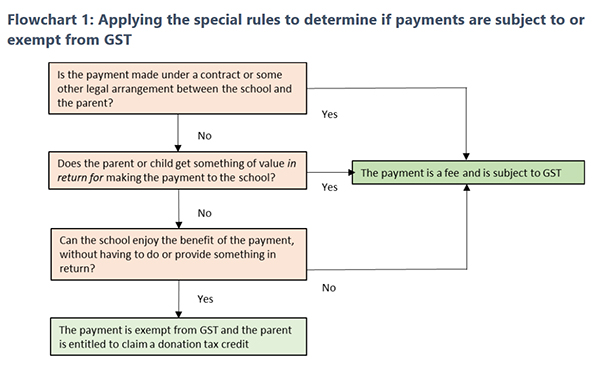

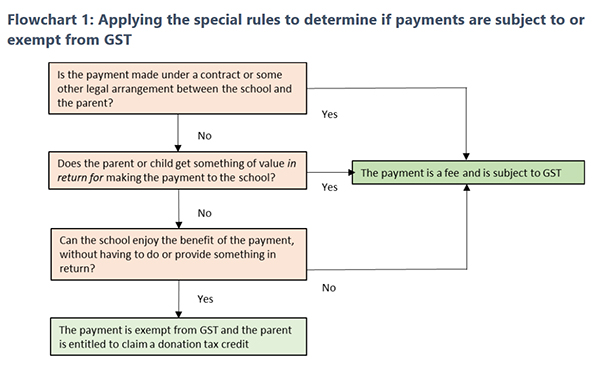

GST and private schools

And finally, private schools have been in the news recently, largely because of the revelations about the behaviour of the newly elected MP for Tauranga. Quite by coincidence, this week Inland Revenue has released a draft Question we’ve been asked on the GST and income tax treatment of payments made by parents to private schools. This also comes with a handy flow fact sheet as well which has a useful flowchart which explains how the rules apply.

Something else to keep in mind are the special rules for calculating GST on school boarding fees. Where students have arranged to board at the school for more than four weeks, the school charges GST at a lower rate (9% or 60% of the standard rate) to the extent the boarding fee is for the supply of domestic goods and services.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

29 Mar, 2021 | The Week in Tax

- A closer look at the Government’s shock property tax announcements

- Four questions on the future of tax

Transcript

It would be fair to say that the shockwaves from Tuesday’s announcements are still reverberating around investors and analysts and tax professionals.

The increase in the bright-line test period to 10 years was widely anticipated. But the move to completely eliminate, over time, interest deductions for residential property investors was a complete shock and has caused quite a considerable amount of commentary.

I would say at this point, I think several people have been extremely ill guided in some of the comments they have made online. Inland Revenue monitors social media, and some of the comments I’ve seen by property investors, understandably, given the shock and the implications for them, upset about what has happened and probably reacting somewhat intemperately, may come back to haunt them.

For example, saying that rent doesn’t cover the cost of a mortgage and other costs, as one investor said in print, is an open invitation to Inland Revenue to raise questions as to why if that was the case, that person had purchased property. It opens the door for Inland Revenue to then go on and say, “Well, you must have acquired that with a purpose or intent of sale.” Which if that is argued bypasses the bright-line test. It doesn’t matter how long you’ve held it in those in those circumstances, any gain will be taxable.

Now, that’s an extreme response Inland Revenue could take. But as I said, I think some people might, to borrow a phrase, that my mother would use “Cool their heels a wee bit” and sit back and reflect on the implications of what’s going on, rather than rushing to social media and excitedly make a comment that they may regret at a later date.

But still, there are good reasons for people to respond passionately given its surprise. Under the Generic Tax Policy Process, changes like this are usually signaled in advance. The Government issues consultation papers, and there’s a back and forth between industry specialists and Inland Revenue and Treasury on the implications of these proposals. That isn’t going to happen here.

In the course of the group call made to tax agents and tax advisors before the announcement, Inland Revenue made it clear that there would be no consultation about the bright-line test period and on restricting interest deduction issue. Inland Revenue would, however, consult around a key point that is emerging. What is the definition of “new builds”?

So these proposals are all outside the normal process and have understandably drawn criticism along the lines of “Can the Government do that?” They can. And in many ways, it’s surprising this doesn’t happen more often in tax policy.

Governments around the world will move very quickly when it suits them or when they feel that they need to close off loopholes. Coming from Britain, Budgets were always full of surprises and policy announcements. Sometimes there might be some leaks ahead of the announcement, but generally speaking, every Budget always contained a few surprises.

Now, the other thing attracting criticism is how the Government has rather deliberately phrased the move against interest deductions as closing a loophole. As a few people have pointed out, this is not correct. The position is that interest borrowed to derive gross income, such as rental income is deductible.

But what has become apparent in the residential property investment market is that there’s two parts of the economic return. There is the rental and then there’s the capital gain.

And the issue was that many leveraged investors who are most affected was that they were getting a full interest deduction but would only be taxed on part of the economic return. That is the rental income. All things being equal the capital gain would not be taxed unless the bright-line test applied. Restricting interest deductions in that context is actually consistent with the general income tax rule that an expense is only deductible to the extent it’s incurred in deriving gross income.

The current treatment is therefore an anomaly. What the Government has done is closed off an anomalous position, but only in respect of a certain group of investors, which again leads to outrage about the treatment. But that group is probably losing that argument about it not being a loophole, because to borrow a political phrase, “Explaining is losing” particularly if as in this instance a very technical argument applies.

Always at risk

But the overall point should be kept in mind, and this has happened before with the removal of the loss attributing qualifying company regime, tax preferred investments or rules that give a tax advantage will always be scrutinised by government. They are always therefore at risk of being abruptly closed off.

So, if you built an economic business model around relying on that, you are actually making yourself very vulnerable to a move like this.

Work in progress?

Moving on, one other point has emerged, which is surprising, and in the context of the General Tax Policy Process, concerning, is that it appears no details of the advice that was given by Treasury and Inland Revenue on the interest deduction move has been made publicly available.

This is surprising because it implies that this policy is still being worked out. As a result of that the fiscal impact is not clear.

If the interest deductions are restricted completely, that means the Government’s tax take will increase. And me and my fellow tax advisors have been crunching the numbers for our clients who will be affected. And we are giving them projections as to the likely additional amount of tax that would be payable. And that potentially could be quite significant, although it could be that property investors deleverage as a result, which may have a wider economic impact.

This whole policy, in fact, is a good example of something that came up at a seminar last night, which I will talk about a little later, the law of unintended consequences. This is something that hasn’t been done before and the consequences are still being worked out. One or two things I think that come to mind is we might see investors make more use of company structures because the corporate income tax rate at 28% is less than the 33% for property held in trust or possible 39% if properties are held individually.

I also wonder whether the Government should be looking carefully at the question of is the loss ring-fencing rule required any longer? One of the reasons that rule was introduced was the ability of people to leverage and get deductions for interest. But then, since interest deductions often represented the biggest single cost at a time when interest rates were higher, if they ran into losses, investors were then able to offset those losses against their other income.

Now, that loophole was closed off with effect from 1st April 2019. But the question remains now, given that the ability to leverage, which was the main issue around the need for loss ring-fencing, has been restricted, do we need the loss ring-fencing rules?

The other thing is, and this is something I think the Government will need to address as it was a stumbling block for the introduction of a capital gains tax, is that any gains will be taxed at a person’s marginal rate. In a company the rate is 28%, but for an individual from 1st April, it could be 39%. So, there’s a lot of unintended consequences and it’s understandable to see why investors feel rather picked on at the moment.

There’s interesting commentary from the Bank of New Zealand which started

its newsletter on this issue by saying that “The New Zealand government is dead set on containing soaring house prices. It has been saying so for some time now and prices have just kept soaring. So it should come as no surprise that their patience has now been exhausted and a full attack on prices is now under way.”

BNZ’s view is “Watch this space.” There will be a lot of arguments around the fall-out of this proposal.

The interest rate restriction rules, as an article in the Herald points out, are actually more restrictive than a similar measure introduced in the UK. What the British did was restrict the rate of the tax relief to the basic rate of tax, roughly 20%. These measures go completely further.

I feel that using something completely unknown whilst a shock to the system, and in line with what BNZ is saying the Government is determined to try and do, is leading the Government into untested waters.

And the alternative might have been to use an existing set of rules, the thin capitalisation rules, which might have achieved much the same sort of objective. But there will be a lot of fallout on this, and it’ll be interesting to see whether there is some tinkering around the edges of these measures.

The bright-line test

On the bright-line test itself, it’s been extended from two to 10 years. And there’s going to be a lot of questions on this about the impact of that, but particularly for people who are in the middle of settling on properties.

Extending the bright-line test period to 10 years has now been passed into law as part of a tax bill. But it has also provided some commentary with useful examples of what happens with sale and purchases underway at the time the proposals were announced.

Basically, if an offer was made before the announcement on 23rd March and accepted before 27th March, then the five-year test would apply. But if, an offer was made on 21st March, but the seller accepted the offer and signed the sale and purchase agreement on 27th March, then the extended 10-year period would apply.

Another of the examples given was of a verbal acceptance before 27th March but the agreement is not actually signed until 27th March. Then the 10-year rule will apply.

So people will have been pressured to making quick adjustments right now to finalise their sale and purchase agreements. Not ideal, and there will be a few people who have been caught on the wrong side of the new 10-year period as a result.

In relation to conditional offers, for example, someone submitted an offer on 18th March, which is accepted, and the agreement was signed prior to 27th March, conditional on finance. If the offer goes unconditional after 27th March, in this case, the 5-year rule would apply. Alternatively, there’s a change in the agreed purchase price which happens after 27th March, the 5-year rule would be applicable.

There’ll be plenty more commentary on this going forward. And it will be interesting to see the commentary in relation to the question of what expenditure becomes deductible as a result of a sale becoming taxable. We don’t know yet if interest expenditure, which has been disallowed, will then become deductible if a property is sold and it’s taxable under the bright-line test or any other measure. The implication is it should be. But we are we’re going to have to wait till May when consultation on this will arrive.

The future of tax

Moving on to an interesting bit of fun I had last night with some colleagues. The New Zealand Centre for Law and Business ran an event where myself, Paul Dunne of EY and Geof Nightingale of PWC where part of a panel.

We were asked four questions around the future of tax. Do we need more tax? Can tax help the runaway residential property market? Will changing demographics result in a changing tax mix? And reducing taxes on the wealthy is this a discredited theory? And if so, what are the implications for that?

This whole thing would be a worthwhile podcast in itself, but it was interesting to see how Paul, who was a member of the 2010 Victoria University Tax Working Group, and Geof, who was a member of that same 2010 tax working group and the recent Sir Michael Cullen-chaired group were mostly in agreement with the need for a comprehensive capital gains tax or rather better designed set of rules around that.

I think the discussion is still there as to whether we need a comprehensive capital gains tax or should it be limited to a particularly troublesome asset class at the moment, property. All of the members of the 2018 Tax Working Group agreed with increasing capital taxes on property. And you’ll note, by the way, some of the discussions that come out about the Government’s bright-line test period, with Treasury suggesting a 20-year period with no exemption for “new builds”.

By the way, as I said we don’t yet know what the definition of “new builds” will be. We’re going to have to wait and see. And on that point, Paul and Geof both made very pertinent points that the law of unintended consequences is very applicable here. They have clients who are involved in property syndicates who were in the process of converting commercial property into residential property. The question now is, are these “new builds”? They don’t know. So, there may be a pause while everyone waits to find out. What does that mean? No-one is going to commit millions of dollars to a project with an unknown tax outcome. So that was one theme of our discussions.

Do we need more tax? The view was that at roughly 30% of GDP, we should be OK. All three of us were in agreement that the ratio of government debt to GDP was not an issue, but we were all not so enamoured of high private debt as we see that as more concerning. So we had an interesting discussion and hopefully I can make the video recording available in due course.

Error correction

And finally, last week, I talked about charging interest at the prescribed rate of interest on overdrawn current accounts. I mentioned that from 1st April 2021 that rate was going to increase from 4.5% to 5.77%.

Well, another of my listeners from Inland Revenue has been in touch and thanked me for drawing their attention to this. It turns out that was a transcription error in their website and that 5.77% rate is incorrect. It will in fact remain at 4.5% going forward. So, thank you Rowan, for getting in touch. And thank you again to all my listeners and readers at Inland Revenue.

Well, that’s it for today, I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next week Ka kite āno!