21 Jan, 2020 | Tax News

ANALYSIS: Who killed the capital gains tax proposal and why? What did that decision cost us? And is it really dead or just resting?

Tax is inherently political, so when looking at who killed the capital gains tax (CGT), the answer is straightforward: it was New Zealand First in the Beehive with its veto. Firmly slapping down Simon Bridges’ attempts to claim credit for the decision, Winston Peters declared: “We’ve heard, listened, and acted: No Capital Gains Tax.”

Curiously, one of Peters’ justifications for NZ First’s veto was that a CGT would unfairly penalise those who had been “forced” to invest in property following the stock market crash in 1987. It’s worth remembering that even if a CGT had been introduced those historic gains would not have been taxed. (This crucial fact was often rather conveniently overlooked during the debate.)

New Zealand First’s decision had the backing of a number of transparently self-interested groups such as the NZ Property Investors Federation but also many smaller businesses who were concerned about the potential impact.

The wider business concerns were a reason why three members of the Tax Working Group (TWG) — Joanne Hodge, Kirk Hope and Robin Oliver — disagreed with the group’s recommendation of a comprehensive CGT. The three considered any potential benefits would be outweighed by increased efficiency, compliance and administrative costs.

However, the TWG was unanimous that there was a “clear case” for greater taxation of residential rental investment properties.

Robin Oliver, a former Inland Revenue deputy commissioner, presented some interesting insights into the failure of the CGT when he and fellow TWG member Geof Nightingale spoke at the Chartered Accountants Australia & New Zealand (Caanz) tax conference last November.

Oliver commented on the visible lack of political support for a CGT, which was in marked contrast to how Roger Douglas and Trevor de Cleene had promoted the introduction of a goods and services tax (GST) in 1985.

Oliver also noted the proposed design was probably too uncompromisingly pure. In his view the politics were always going to be difficult and compromises would be needed to cross those hurdles.

Incorporating some form of inflation adjustment was another potential compromise. This is common in jurisdictions with a CGT. Australia, Canada, South Africa and the United States all do not tax the full amount of a gain. Instead, the gross gain is reduced by between 40 per cent and 50 per cent, with the net amount then taxed as if it was income.

The United Kingdom does tax the full amount of the gain but applies a different tax rate linked to the taxpayer’s total income. Interestingly, that tax rate can be higher if the gain relates to property.

Neither of these compromises were ever floated and so the CGT was effectively left to wither and die.

WHAT WAS THE COST?

What did the decision to shelve the CGT cost? For starters, the TWG modelled four revenue-neutral scenarios for redistributing the $8.3 billion a CGT was projected to raise over the first five years.

All four scenarios included personal income tax reductions of at least $3.8b over the five-year period, with the most generous scenario suggesting income tax reductions of $6.8b.

For many people, the decision not to adopt a general CGT meant they lose out on lower income taxes. However, a cynic might say that for residential rental investment property owners the continuing benefit of untaxed gains far outweighs any such benefit.

The decision not to adopt a general CGT does nothing to break New Zealand’s long-running pattern of over-investment in residential property.

The decision also does nothing to break New Zealand’s long-running pattern of over-investment in residential property, which means little real progress can be made on addressing housing affordability. There is therefore likely to be an ongoing cost for those Millennials and Generation Zers wanting to own their own property.

There’s a wider concern that funds which could be used for productive investment will be increasingly diverted into residential property, particularly in the wake of the increased capital holding requirements for banks.

DING DONG THE WITCH IS DEAD – OR IS IT?

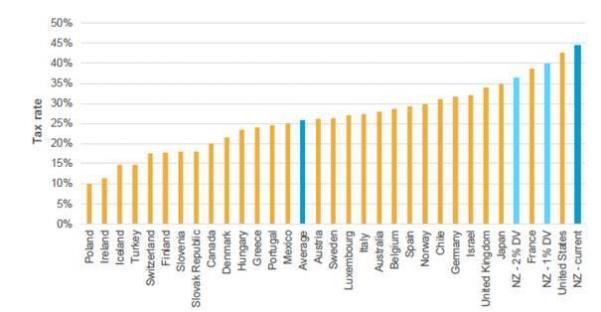

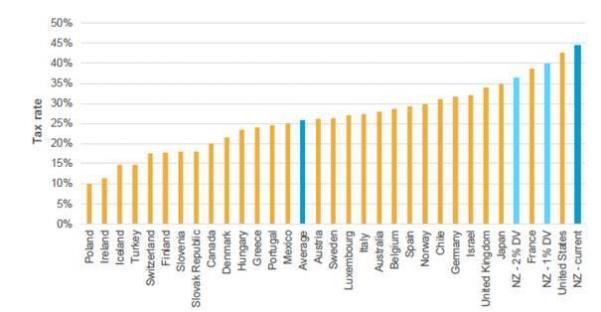

New Zealand therefore remains an outlier in world tax terms in not having a generally applicable CGT. But it is not as if no capital gains are currently taxed. The tax system has nearly 30 separate provisions taxing some form of capital gain.

This includes a general provision which will tax any gains made from disposals of personal property if the property was acquired “for the purpose of disposing of it”. Critics of a CGT also ignored that it would have brought a certainty of treatment to all transactions.

In the absence of that certainty, taxpayers cannot always be certain that a property sale will be non-taxable. Tighter enforcement of the existing rules by Inland Revenue is very likely.

As a sign of this, I have recently become aware Inland Revenue is reviewing property transactions from as far back as 2012. Although these disposals pre-date the introduction of the bright-line test in October 2015, it appears they would have been taxable if the test had existed at the time of sale. The spectre of CGT therefore remains.

Robin Oliver concluded his comments at the Caanz tax conference by noting that although he remained opposed to a general CGT, he did not consider the present under-taxation of residential rental investment properties was sustainable in the long run.

Nightingale supported that assessment. Both were undecided as to whether a CGT was the best means of addressing the issue of under-taxation. An alternative might be to apply the deemed return approach used to tax overseas shares in the foreign investment fund regime.

It’s therefore wise to assume that CGT is not dead but merely resting. My expectation is that the debate will emerge in force towards the end of this decade as the rising cost of superannuation and health costs for the elderly puts increasing pressure on government finances.

By then inter-generational frustration with housing affordability may mean voters are ready to back change. We shall see.

This article was first published on Stuff.

20 May, 2019 | Tax News

Tax is full of unintended consequences and one such instance is probably critical to Jenée Tibshraeny’s exposé of the problems many bodies corporate of apartment blocks now face.

The story begins in January 2010 when the Victoria University of Wellington Tax Working Group (the VUW TWG) released its report. The VUW TWG’s key recommendation was for the personal, trust and company income tax rates to be aligned as far as possible. This would involve a reduction in the top personal income tax rate from 38% to 33%. The VUW TWG also commented on the need for the company income tax rate to remain competitive.

The VUW TWG also recommended broadening the tax base “to address some of the existing biases in the tax system and to improve its efficiency and sustainability.” It then noted that base-broadening would be “required if there are to be reductions in corporate and personal tax rates while maintaining tax revenue levels.” The VUW TWG suggested that one such base-broadening measure could be an increase in the rate of GST from 12.5% to 15%. Another measure could be “Removing tax depreciation on buildings (or certain categories of buildings) if empirical evidence shows that they do not depreciate in value.”

The evidence presented to the VUW TWG indicated commercial and industrial properties did in fact depreciate in value. However, this didn’t appear to be the case for residential properties.

Accordingly, the initial costings for the 2010 Budget only proposed the removal of depreciation on residential properties. This would raise approximately $340 million in its first year which would help pay for the proposed income tax cuts. Once it was decided to reduce the company tax rate from 30% to 28% (a measure expected to cost $410 million in its first year), the decision was also taken to remove depreciation from all buildings. This raised a further $345 million towards the personal income and company tax cuts.

The National Government duly adopted the VUW TWG’s tax rate alignment proposals, announcing these in its 2010 Budget released on 20th May. With effect from 1 October 2010 personal income tax rates and thresholds would be adjusted and the present top personal rate of 33% introduced. The rate of GST would increase to 15% with effect from the same date and tax depreciation on all buildings would be removed with effect from the start of the 2011-12 income year (1 April 2011 for most taxpayers).

Then the Canterbury Earthquakes happened.

By 1 April 2011 it was quite apparent that owners of commercial and residential investment properties in Canterbury faced significant repair and/or rebuilding costs. Furthermore, all commercial property owners throughout New Zealand would also need to carry out seismic strengthening at a cost initially estimated to be almost $1.4 billion.

Owners of investment properties also had a big tax problem – was the cost of repair and seismic strengthening work tax deductible? Prior to 1 April 2011 if expenditure wasn’t deductible it could at least be depreciated. Repairs were probably deductible but investors rebuilding properties could no longer claim a depreciation deduction unless they could demonstrate the building’s life would be under 50 years. As for seismic strengthening the tax treatment was unclear – were they a repair and therefore deductible or an improvement and non-deductible?

This unsatisfactory state of affairs has continued since then. It caught the attention of the latest Tax Working Group (the Cullen TWG). It noted that the withdrawal of depreciation now meant that by 2015 New Zealand had the highest effective tax rate for foreign investment into both manufacturing plants and office buildings among OECD countries.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG estimated the fiscal costs over five years of these various options as between $70 million (seismic strengthening only) and $1.46 billion (industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings).[1] They were, of course, conditional on the availability of additional revenue from the extension of the taxation of capital gains.

As we know, that isn’t happening but fortunately the treatment of seismic strengthening is one of the Cullen TWG’s recommendations which is a high priority for inclusion in Inland Revenue’s tax work policy programme. Frankly, nearly nine years after the Canterbury Earthquakes first hit, this is a well overdue move.

The Cullen TWG interim report in September 2018 also had some commentary on the effects of the reduction of company tax rates in 2010.

“The two most recent reductions in the company rate in New Zealand – in 2008 and 2011 – were not associated with an increase in foreign investment. In fact, the stock of foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP trended down slightly in the following years. There was also no increase in the level of foreign investment relative to Australia, whose company rate was unchanged during that period.”[2]

In short, New Zealand didn’t get much return in the form of foreign direct investment for its cuts in the company tax rate.

There is perhaps one final irony at play here: holders of investment properties were among the fiercest critics of the Cullen Tax Working Group’s recommended capital gains tax. Did they win that battle at the cost of the loss of the reintroduction of building depreciation? If so, may that win turn out to be a Pyrrhic victory?

[1] Table 6.1, Chapter 6

[2] Para 21, Chapter 14

This article first published on Interest.co.nz

25 Feb, 2019 | Tax News

When hearing the lamentations about the purported cost and harshness a capital gains tax (“CGT”) will bring, I think of Paul1. Dying of cancer he applied to his UK pension scheme for an early payment. Paul died before it arrived, but his widow still got to pay the tax on the transfer.

I am reminded of Judy and Wayne, hard-working specialist nurses living in Auckland, who also transferred their UK National Health Service pensions to New Zealand. They too got a tax bill for their troubles even though it would be five years at the earliest before they could withdraw any cash. Judy and Wayne could not even withdraw funds to pay the $50,000 tax bill. So, in order to meet the bill, a pair of highly skilled nurses in a sector and city with chronic shortages, sold up and moved to the South Island. A real triumph of tax policy.

Nothing the TWG proposes in its final report will be anywhere near as penal as the present rules for taxing foreign superannuation schemes. Or, for that matter, the financial arrangements and foreign investment fund (“FIF”) regimes that will also remain in place. Amidst some of the frankly hysterical reaction these important details have been overlooked.

Listen to Terry discussing the TWG report with Jenée Tibshraeny journalist at Interest.co.nz

The TWG proposes extending the range of assets that will be specifically taxable on disposal. It’s therefore not a CGT in the sense of a specific part of the Income Tax Act covering all capital transactions. Rather it is, to borrow a phrase, a backstop, applicable if the transaction isn’t taxed elsewhere.

I do not read too much into the minority report by three of the TWG members. It is unusual but should not be a surprise: tax experts by their very nature are an argumentative bunch at the best of times and are as divided over the issue as the general public. What is interesting about the minority view is that all three, including long-time CGT sceptic Robin Oliver, support taxing disposals of residential property.

That, together with comments in the report that the Government doesn’t have to accept all the TWG’s proposals about extending the taxation of capital, opens the door for a partial extension only on residential property investment.

The issue will dominate politics between now and next year’s election and the Government will need to decide quickly if the relevant legislation is to be in place before the proposed start date of 1 April 2021. In this context, Inland Revenue’s capability to deliver will be tested, which prompted Michael Cullen to remark that it might need support from countries that have CGT regimes to help get the legislation ready. He and the report also stressed the need of ensuring Inland Revenue is properly resourced and keeps its most skilled staff, which according to Cullen isn’t happening at the moment.

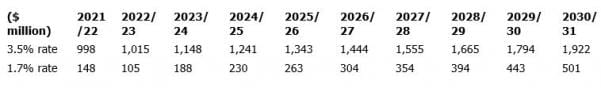

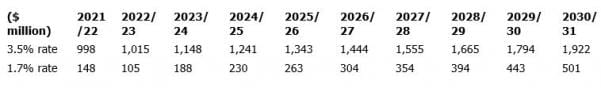

Although a CGT is the preferred option, the TWG report does consider the use of a deemed return method similar to the fair dividend rate applicable under the FIF regime. Table 5.1 of the report suggests that the deemed return method could immediately raise more tax than adopting the CGT approach depending on the deemed rate of return applied:

Deemed Return Rate for CGT

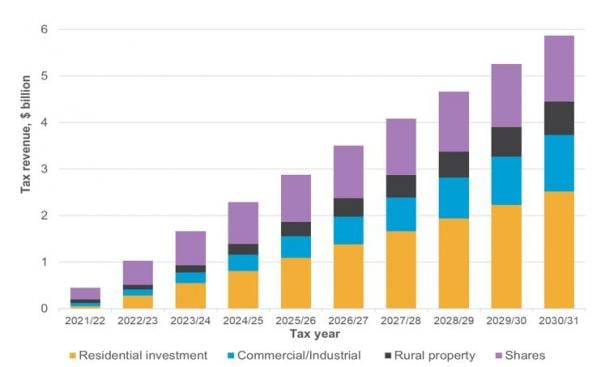

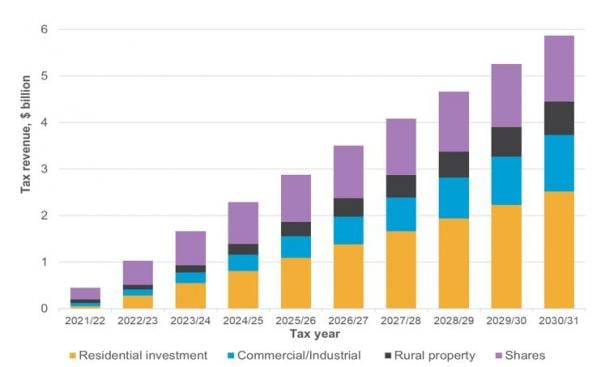

According to the TWG, the projected revenue from a CGT over the first ten years rises from $400 million in the first year to $5.9 billion by 2030/31.

Future Tax Revenues estimate from Capital Gains TaxT

After ten years CGT would represent 1.2% of GDP and a not insignificant 4.2% of total tax revenue.

That raises an interesting point about how a Government might react if a downturn affected tax receipts from CGT. This was a very real problem for California and New York State in particular in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis. The deemed return method’s predictability of tax receipts is one reason why it might still be an option.

As noted above the broadening of the taxation of capital income doesn’t replace existing rules such as the FIF and financial arrangements regimes. With regard to the FIF rules, the TWG recommends that the FDR method should be retained. It does consider the present 5% rate should be able to be adjusted frequently as economic conditions change. However, the TWG considers the current ability for individuals and trusts to adopt the alternative comparative value (CV) method if it is lower than FDR as;

“anomalous and inconsistent with the idea behind taxing a risk-free return. It also potentially creates a bias in favour of non-Australasian shares because taxpayers are subject to a maximum 5% rate of return but can elect the actual rate of return if it is lower…. If the FDR rate is ultimately lowered from 5%, the Group recommends removing the ability to choose to apply the CV option only in years where shares have returned less than 5%”

Such a move would increase the tax payable by individual investors unless the FDR rate was set at a level which was fiscally neutral. But it highlights the complexity which will still remain if a CGT approach is adopted.

Volume II of the report has the design details of the proposed CGT.

Two areas of the design have provoked a fair amount of commentary, the treatment of inflation and the proposed valuation day approach.

At first sight the criticism regarding the proposal to adjust for inflation seems reasonable. But as the interim report noted the tax system doesn’t adjust for inflation generally at the moment. Furthermore, as Cullen noted at the briefing the amount taxed under a CGT approach is often lower than that payable under an annual accrual-based approach.

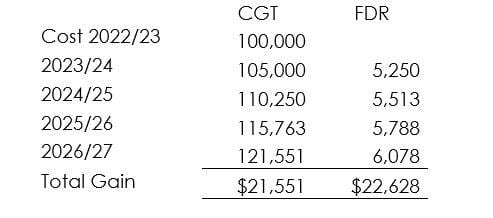

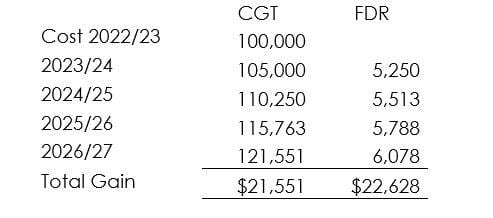

For example, compare the totals taxable between a CGT approach and under the foreign investment fund fair dividend rate method. Assuming $100,000 is invested, which grows at 5% per annum and is sold after four years under CGT, the taxable gain will be $21,551. This is less than the total of $22,628 taxed under the FDR method (generally no income is taxed under FDR in the year of acquisition).

Capital Gains Tax versus Fair Dividend Rate

The TWG proposes that under the CGT approach only gains arising from the date of implementation will be taxed, the so-called “Valuation Day” method which both Canada and South Africa adopted when they introduced their respective CGT regimes.

The potential compliance costs involved have been criticised so the TWG proposes taxpayers should have five years from implementation (or to the time of sale if that is earlier) to determine a value. They also suggest a couple of default methods for assets held on Valuation Day. These are either the straight-line basis or the median method, helpfully illustrated below.

John purchased a small trucking business on 1 April 2015 for $200,000. On 31 March 2025, John sells the business to Paul for $600,000 (i.e. a $400,000 gain).

As a result of the extension of the taxation of capital gains, John will have to pay tax on the capital gain he has derived since Valuation Day (1 April 2021) from the sale of the business (i.e. for the last four years he has owned the business).

Applying a straight-line approach, John will have to pay tax on 4/10th of the gain on sale (i.e. $160,000).

Example business valuation and CGT

The median rule determines the deductible cost as the median or middle value of actual cost (including improvement costs), the value on Valuation Day, plus improvement costs, and the sale price.

In 2014 Scott bought a rental property for $500,000. On Valuation Day the property was valued at $450,000. Scott sold the property six years after Valuation Day for $850,000.

Applying the median rule:

Cost = $500,000

Valuation Day value = $450,000

Sale price = $850,000

The median value is $500,000. Therefore, Scott is able to deduct $500,000 from the sale price of $850,000, giving rise to a $350,000 taxable gain.

Without the median rule, Scott would have a taxable gain of $400,000 (i.e. sale price of $850,000 – price on Valuation Day of $450,000) despite only making a gain of $350,000 over the whole period he owned the property.

There is, as you’d expect, a wealth of detail in these proposals including some anti-avoidance provisions to prevent “bed and breakfasting” as a means of accessing losses. Some losses will be ring-fenced but in general most capital losses should be able to be offset against other income.

There’s plenty more elsewhere to consider in the report such as the proposals for KiwiSaver and the surprising suggestion that the Government “give favourable consideration” to exempting the New Zealand Superannuation Fund from tax. I’ll cover these and other snippets separately.

This post first appeared on Interest.co.nz

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.

The Cullen TWG final report therefore recommended the Government consider restoring depreciation deductions for buildings “if there is an extension of the taxation of capital gains”. Alternatively, the reinstatement could be on a partial basis either for seismic strengthening, multi-unit residential buildings or maybe industrial, commercial and multi-unit residential buildings.