- PM’s Department warns IRD off looking at a CGT

- The IRD admits not having the data on non-compliance with fringe benefit tax

- Residential property investment looks very undertaxed compared to other investments

Transcript

After the dramas of last week’s tax bill being introduced and then withdrawn within 24 hours, it’s been a calmer week in tax. On Thursday the tax bill was reintroduced without the offending provisions relating to GST on fund manager services. Interestingly, there has been some more measured discussion as to the merits of that proposal, and I do wonder whether a government might introduce an amended proposal at a later date, perhaps this time with any GST raised use to boost incentives for lower income Kiwi savers, such as the proposal made by the Tax Working Group.

Elsewhere this week, I got involved in some interesting debates over the question of whether the tax thresholds should be raised. My view is yes, but on the Today FM show, Max Rashbrooke made the alternative case for better targeting of low-middle income earners. I agree with host Tova O’Brien that tax is going to be a big issue in next year’s election. And like many of us she was looking forward to seeing what the tax policies of the various parties would be.

Whatever policies we’ll see next year will be they’re almost all certain to address the issue of raising productivity in New Zealand and what part tax and economic policy will play in achieving that goal. And that is the subject of an interesting paper released by Inland Revenue just a couple of weeks back. This is the first long-term insights briefing which public service agencies are required under the Public Service Act 2020 to publish at least once every three years. These briefings are designed to provide information on medium and long-term trends, risks and opportunities and provide, “impartial analysis on possible policy options”.

Inland Revenue’s chosen subject was Tax, foreign investment and productivity. A really meaty topic and the whole paper runs to 111 pages. As the briefing explains, it examines how New Zealand’s tax settings are likely to affect incentives for firms to invest into New Zealand and also benchmark our tax settings against those in other countries.

The initial evidence is that, compared with other OECD countries, we appear to have relatively high taxes on inbound investments. This then gets down to the question whether those tax settings are

“likely to mean higher costs of capital (or hurdle rates of return) for investment into New Zealand than for investment into most other OECD countries. High taxes on inbound investment have the potential to reduce economic efficiency and be costly to New Zealanders by reducing New Zealand’s capital stock and labour productivity.”

I think economists would be looking at this paper with some great interest as well. Now, the OECD analysis that is often used for comparison purposes looks at company tax provisions. But this paper also notes that there are other broader tax issues that should be taken into consideration. And when you take a broader perspective, maybe New Zealand isn’t as much as an outlier as it first appears.

What the briefing is intended to do is, “initiate a process of discussion on these sorts of issues.” The briefing considers several possible tax changes, namely:

- a cut in the company tax rate

- accelerated depreciation provisions

- inflation indexation of the tax base

- a higher thin capitalisation rule safe harbour

- an allowance for corporate equity

- special industry-specific or firm-specific incentives, and

- a dual income tax system.

These measures are all possible ways of lowering the costs of capital. And some of those can also promote tax neutrality. However, there is unlikely to be a single best option, and choices between the options will ultimately depend on what weightings are given to the possible objectives of reforms. Of course, politics comes into play, for example, a lowering corporate company income tax rates for non-resident investors isn’t going to be terribly popular because that might mean higher tax rates for individuals. Therefore, there are these series of tradeoffs that have to be considered.

The briefing is accompanied by 45 pages of appendices. Some of the papers referenced are quite interesting. One in particular caught my eye, was prepared in 2016 by a couple of American economists relating to accelerated depreciation allowances, a measure that’s often promoted. As there’s a wealth of data available in America, these economists and analysed data for over 120,000 firms.

They presented three findings. First, accelerated depreciation raised investment in eligible capital relative to ineligible capital by 10.4% between 2001 and 2004 and then by 16.9% when it was reintroduced between 2008 and 2010. Their second finding was that small firms responded 95% more to that incentive for accelerated depreciation than larger firms. I think this is particularly important in the New Zealand context. Finally, firms responded strongly whether these policies of depreciation in generated immediate cash flows, but not necessarily when cash flows were in the future. In other words, firms were very interested in short term quick return investment. Now, given that I think our smaller firms are under-capitalised and we have lower productivity, obviously one of the points for future discussion from this briefing is about the role of accelerated depreciation.

Now, the object of the briefing isn’t to propose a single solution. It is, “…to start a conversation on what people see as the most important objectives for reform and whether particular reforms are worth considering further.”

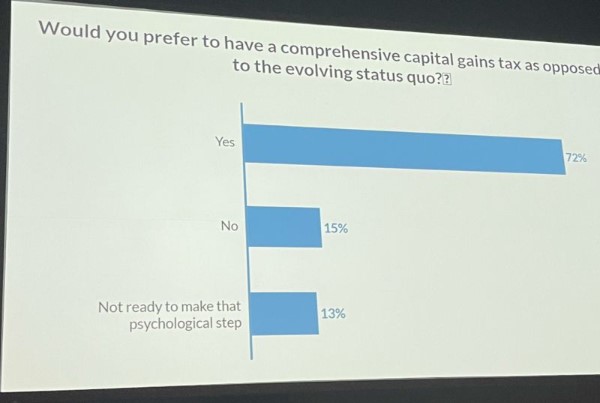

When Inland Revenue initially put out an issues paper saying this was the proposed subject of its briefing it asked for responses. A few replied raising the issue of how the absence of a capital gains tax just reduces the coherence of the tax system, and there may be productivity concerns because of the light taxation of property. The briefing addressed these issues as follows:

“The Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet has advised that briefings should not focus on issues that have already been subject to considerable analysis. Capital gains tax was considered by the recent tax working group and the government decided against a general tax on capital gains. Therefore, we, the briefing, are not making a capital gains tax on property or a more general tax on capital gains a central focus because it has been the subject of recent debate and policy consideration.”

The problem with this approach is this is a meant to be a long-term insights briefing, and taking capital gains out of the picture immediately circumscribes its value. And by the by, in most cases, any foreign investors are subject to capital gains tax in their own country. Capital gains tax is a factor anyway for offshore investors and so maybe we should be factoring it in here.

To be fair, once you’ve gone through the paper and you understand what is driving it, the absence of commentary on capital gains tax although disappointing, shouldn’t be a distraction from what is a very interesting and valuable paper with plenty to digest. I do recommend reading this as it contains some very interesting issues, such as the idea of a dual income tax system which individually could be the subject of a podcast.

FBT reviewed

Moving on Inland Revenue has also released its 49-page Fringe Benefit Tax regulatory stewardship review. This is something else required under the Public Sector Act 2020 which requires regulatory stewardship reviews to ensure that policy and operational responsibilities are effective and operating as intended. Last week I mentioned how the new tax bill reintroduced this week gives an exemption from FBT for the provision of public transport. I noted the current treatment as an example where one set of tax policies probably doesn’t sit well with a wider set of objectives

FBT was chosen for review because it hasn’t been fully reviewed since some minor changes were made nearly 20 years ago. And as the review notes, over time, stakeholders have raised problems with the design and operation of FBT. The review is seen primarily as a diagnostic exercise investigating three questions:

- Does the design of FBT meet the policy intent?

- What is the employer and business experience of complying with FBT?

- How does Inland Revenue administer FBT?

The review also considers whether FBT as in its current format is fit for the future, taking current workforce trends into account with more and more people working from home now.

The summary conclusions are that it does perform its primary task of ensuring that remuneration from employment is taxed, whether it’s paid in cash or provided by way of a non-cash benefit. FBT is one of those taxes which is as much designed to support the tax base by tackling anti avoidance behaviour as well as raise tax. But as the review then notes

“However, it is not clear that FBT is a tax that functions well. Consistently, views expressed to the review team were that FBT is complex and that it imposes a high administrative and compliance burden relative to the tax at stake.”

There was also this interesting feedback “many interview participants felt that any intuitive connection with remuneration had been lost.”

FBT was introduced in 1985 to counter an avoidance of PAYE on salaries by providing people with non-cash benefits. Initially it had a very important role, particularly since back then tax the top tax rate was still 66%. However, a lot has changed in the last 37 years.

One of the main points that comes out of the report is that submitters feel FBT is not being complied with by all businesses and it’s not being enforced by Inland Revenue. This is seen as unfair by those who shoulder the compliance burden. The official response is “Inland Revenue is unable to comment on the amount of non-compliance with the FBT rules using existing data, although the use of START at its new computer will enable a more timely and targeted compliance approach.”

That is a hell of an admission. The review then points out if non-compliance with FBT rules is perceived to be risk free, then that perception could undermine the integrity of the tax system as a whole. Therefore, this risk needs to be addressed.

The review then puts up a couple of proposals to do so. Firstly, which many might see as a bureaucratic answer, commission a policy project to act on the findings of the review. This would be to conduct an enquiry into fundamental reform, for example moving benefits-in-kind into the PAYE system. That was something not supported by interviewees. Secondly, “requiring operations to take steps to address the concerns raised about compliance and enforcement”, which might be more crudely and accurately expressed as “Do your damn job Inland Revenue”. And that is where I would begin.

We probably should have a review of fringe benefit tax and how it operates and whether the current system is fit for purpose. It definitely is compliance intensive. And there’s also this widespread perception of non-compliance, particularly in in in in regard to the definition of work-related vehicle and the rise of the twin-cab ute and whether such vehicles are genuine work-related vehicles. At the same time, I believe you have to enforce the current law because the perception might arise that the integrity of the tax system is being undermined. That’s actually in breach of official’s duties under the Tax Administration Act. I think it does no harm to show that compliance of the rules is required. Plus, it might raise a little bit of extra revenue.

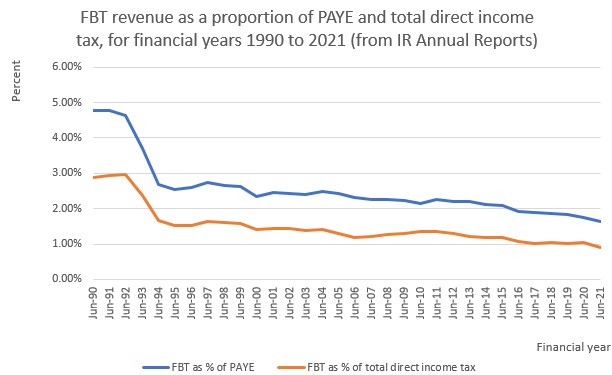

There is some interesting commentary about how much revenue FBT does raise. For example, in the 2019/20 tax year, the Inland Revenue collected $592 million of FBT, which is 24% up on the $479 million collected in the 2009/10 tax year. However, back in the early 1990s FBT revenue was close to 5% of PAYE revenue and around 3% of direct income tax revenue. But now it’s closer to 1.6% of total PAYE revenue and about 0.9% of total direct income tax revenue.

FBT revenue rose steadily between its introduction and 1989 but then significantly reduced between 1990 and 1995. This decline may be the result of changes to the definition of benefits subject to FBT, but it may also reflect employers responding to its advent and switching to cash only salary packages. There may also have been some tax planning around trying to mitigate FBT.

FBT is paid by a relatively small number of taxpayers. Nearly 69% is paid by employers of 101 or more people. And in fact, that according to Inland Revenue data. Employees with 501 or more employees represent just 2% of all FBT filers, but 41.4% of all FBT paid for the year ended 31st March 2020.

For me the key takeaway here is that Inland Revenue really needs to begin to put some resources into management of FBT. I have heard commentary that it didn’t feel it was worthwhile, but there are spin-off effects. As noted, the perception of the integrity of the tax system is undermined. And also, there’s the wider policy objectives we mentioned. If FBT isn’t being monitored, how does that fit with the wish to reduce emissions? If it turns out people think, well, actually, work-related vehicles don’t pay FBT, then people might continue to use relatively inefficient vehicles. We’ve seen, by the way, with the green car discounts, how much an incentive in terms of cashback has made a difference with new registrations. Moving FBT perhaps to an emissions-based charge such as they do in Ireland and the UK, might have some interesting implications and help drive down emissions.

One of the drivers behind the long-term inside’s briefing is that changes to the tax settings will drive foreign investment. It’s not a particularly revolutionary insight. There’s no doubt tax affects investment decisions.

Tax affects investment decisions

A very clear example of that, in my view, is when we consider the taxation of residential investment property, which I discussed with RNZ’s The Panel on Wednesday. This stemmed from an Official Information Act request I made to Inland Revenue asking for details of the number of taxpayers returning residential property investment income, how many reported net positive income, how many reported losses and what was the net income returned.

I shared my information with Geraden Cann of Stuff who ran the story.

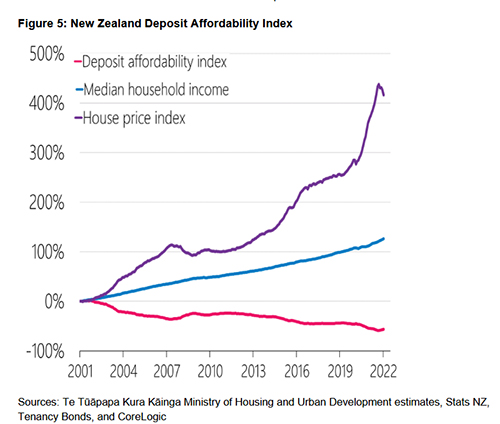

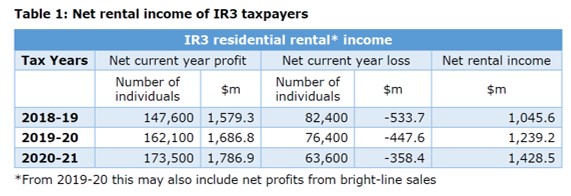

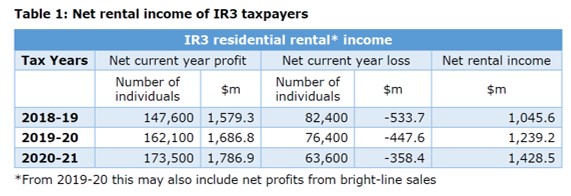

In summary for the year ended 31st March 2019, 36% of all those filing individual tax returns and reporting rental income incurred a loss. For the year ended 31st March 2020 that proportion fell to 32%, and in the year ended 31st March 2021, it fell further to 27%. As you can see in the year ended 31st March 2021 about 240,000 people reported rental income with 173,500 in profit but 63,600 with losses amounting to $358 million. The net income rental income reported for the year was $1.428 billion. According to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand’s statistics, the valuation of residential investment property as of 31st March 2021 was $369 billion. That represents a pretty poor 0.4% return pre-tax.

So why are investors investing in residential property then? Because that return is not much better than you might have got if you put your money in the bank. The obvious answer to that is hoped-for tax-free capital gains plays a part in their decision-making. that. To be fair, that’s an understandable investment decision. If property prices are going to rise 20%, and you’re not being taxed on that 20% gain and you’re generating sufficient income to manage your costs, which is what two thirds of taxpayers seem to manage, then that’s not an unreasonable investment decision.

But at some point you have to realise that investment, which does beg the question which has been addressed in another academic paper, can you actually say that you did not purchase with an intent of sale. How otherwise does the investment makes sense without having to sell it?

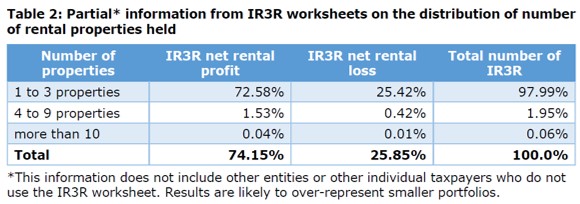

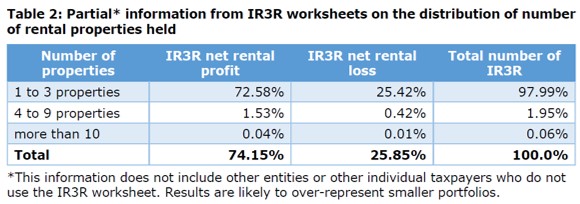

I also asked for a breakdown of the number of residential properties held. Inland Revenue ‘doesn’t have comprehensive information’ so it responded

“We do, however, hold partial information based on the IR3R calculation worksheets used by a subset of around 60,000 property owners who use this form as an input to their filing. Proportions calculated from this subgroup of taxpayers for the 2020-21 tax year are provided in Table 2.

The IR3R calculation worksheet tends to be used by unincorporated taxpayers (individuals or trusts) who are likely to have smaller investment portfolios. The supplied proportions are not necessarily representative of the wider picture incorporating all residential rental taxpayers and all entity structures.”

As you might expect, 25% of all those holding between one and three properties report a loss. The proportion holding between 4 and 9 drops to 0.42%. Quite remarkably, among those with ten or more properties, 0.1% do report losses. One suspects that group are extremely heavily leveraged, and probably these positions are likely to change as interest limitation rules take effect.

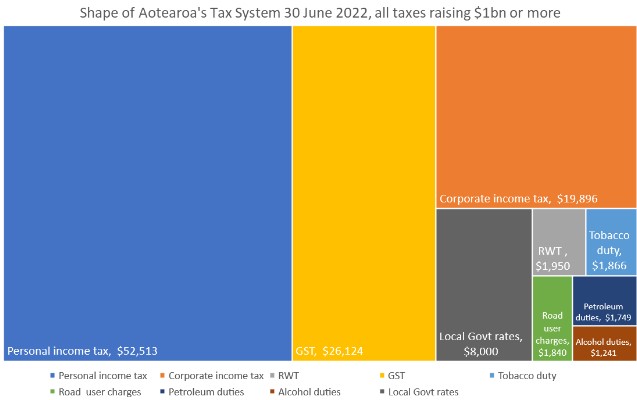

Context

To put this in context, the Financial Markets Authority publishes a KiwiSaver Annual Report. This details the number of KiwiSaver schemes, the value of those schemes and actually the income reported and tax paid by all KiwiSaver schemes. The total value of KiwiSaver schemes was $81.6 billion and the total tax paid by KiwiSaver schemes was $474.6 million.

As I mentioned, the net pre-tax profit for the year ended 31st March 2021 for investment properties was $1.42 billion. Assuming a maximum 33% tax rate, that would equate to roughly $470 mln in tax. In fact, it’s almost certainly a lot lower because of not every taxpayer with investment property would be taxed at 33%.

When you look at the amount of capital invested in housing, $369 billion and the amount of capital invested in KiwiSaver, $81.6 billion, there’s approximately 4.5 times more capital invested in housing. But the taxable returns are so much lower that relatively speaking, they’re a quarter of KiwiSaver returns so the tax take ends up being broadly similar.

A really big question therefore arises around the efficiency and allocation of capital. That is why it is a bit disappointing Inland Revenue’s long-term insights briefing didn’t address that matter. But I understand that Treasury has been looking the housing issue and has come to the conclusion that tax settings have been a real driver of house price inflation. As I said on RNZ people have made rational decisions to invest in property but those also come with consequences.

And in my view, one of those consequences is inefficient allocation of capital. We also have rising inequality and essentially the arrival of a landed gentry, which means that if you do not have parents or family that can help you into housing, you’re likely to be unable to ever get on the property ladder. That’s not a particularly great scenario to have and coming back to the point Tova O’Brien made is something that next year we should be seeing the politicians talk about the sort of tax policies which address all these issues.

Revisiting 1952

And finally, our condolences to the Royal Family on the passing of the Queen. Just to put her 70-year reign in context, the population of New Zealand in 1952, when she became Queen, was just under 2 million. The Government’s total tax receipts for the year ended 31 March 1952 were just over £200 million or approximately 25% of GDP.

Some interesting taxes used to apply back then including an ‘Amusement tax’ which collected £308,000. The top tax rate was 60% and there was also Social Security in addition. Income tax represented 49% of all tax collections (it’s now nearly 67%). Incidentally, Land Tax, Death and Gift Duties, all now repealed, collected more than £9 million or 4.6% of the tax take. Taxes change over time. But it’s interesting to be coming back to the question of taxing capital. We didn’t have a capital gains tax in 1952, but we did tax capital. Maybe the pendulum is swinging back again.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!