16 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Inland Revenue consults on the OECD Pillar Two GloBE rules for New Zealand and has a new CEO

- Working for families consultation

- A look ahead to next week’s Budget

Transcript

Last year, the G20 and OECD agreed on a two pillar solution to the issue of international taxation and in October 2021, this two pillar solution was endorsed by over 130 countries in what is deemed the OECD sponsored Inclusive Framework. New Zealand was one of the signatories to that endorsement.

Inland Revenue has now released an issues paper looking at how these so-called GloBE rules (Global anti Base Erosion) would operate. Now as this is an issues paper it does not represent government policy. Instead, Inland Revenue is putting the matter out for consultation because the government has not yet decided whether in fact it will adopt Pillar one or Pillar two, and in fact is also not ruled out adopting a digital services tax. So, this issues paper is a basis for formulating policy to be taken to the government. It therefore partly represents a background paper, but also explains how the rules would operate.

To recap, the purpose of the GloBE rules is to ensure that affected multinational groups (MNEs) pay at least a 15% tax on their income in each country where that income is reported for financial reporting purposes. It’s initially intended to apply to MNEs if their annual turnover exceeds €750 million per annum in two of the last four years. It’s estimated to initially apply to approximately 1500 multinational groups worldwide, of which approximately 20 to 25 are based in New Zealand. The OECD estimates that the global revenue gains under Pillar two will be in the order of US$130 to $185 billion annually, which represents about 6 to 7.5% of global corporate income tax revenues.

The paper is split into three parts. Part one is a general overview with Chapter one giving the background on the initiative and on its intended purpose. Chapter two has a summary of the rules in general, and chapter three raises the question which may seem odd ‘Should New Zealand adopt the GloBE rules?’ Part two then explains the proposed rules in more detail, and part three then covers all specific issues form a New Zealand perspective,

The paper is quite comprehensive running to 84 pages so there’s quite a bit of detail to go through here. Fortunately, we’ve got quite a good period of consultation because consultations open until 1st July. Normally we only have a 4-to-6-week period for consultation.

Now, as I said, what may seem a rather strange question is whether New Zealand adopts the rules is a key part of the consultation. The official view is that if a critical mass of countries do adopt or are likely to adopt the global rules, then officials would recommend New Zealand take steps to join them. Officials take the view that they see no benefit, or not much benefit, in New Zealand going it alone and adopting global rules without a critical mass.

Three questions are put to submitters on this issue.

- Do you think New Zealand should adopt the GLoBE rules if a critical mass of other countries does or is likely to do so?

- Do you have any comments about what a critical mass of countries would be?

- Do you have any comments on the timing of adoption?

Now my response would be ‘yes’, New Zealand should, because it’s part of being a good corporate global citizen. Obviously, there’s a likelihood of additional revenue gains, although according to the paper the potential gains are said to be modest.

What would represent a critical mass of countries? Well, that’s a difficult one. I guess the key country to being involved would be the United States. But as you know, they’ve always ploughed their own furrow on this matter. And politics are such that the Midterm Congressional elections may mean that the Republicans are able to block change on this. Like we’ve said in the last couple of weeks when discussing possible wealth taxes, it all comes down to politics. But certainly, if the majority of the 130 countries that have endorsed it do sign up, you’d think that we would want to go ahead even if the United States didn’t. But it would be disappointing, obviously, if America did not.

And then about the timing of these rules this is actually quite tight. Under the Pillar 2 proposals, there is an income inclusion rule which will impose the top up tax on the parent entity in a multinational group. Now under the OECD timeline that should be enacted during 2022 in order to be effective in 2023. And then there’s another part, the under-taxed profits rules, which should come into effect in 2024. I think that timeline is pretty optimistic. I would be expecting to see it slide out a bit, but who knows what the international mood is on this? Maybe progress happens much more quickly than we expect

Anyway, this is an important paper and there’s a lot to consider here. Maybe the gains might be modest, but it is part of the change in international taxation, which will have ripple effects all the way through the tax world

Issues for the recycled ‘new’ IRD CEO

Moving on, Inland Revenue has a new CEO, Mr. Peter Mersi, who has been appointed for five years with effect from 1st July. He takes over from Naomi Ferguson, who has been the CEO of Inland Revenue for the past 10 years and has seen the department through the Business Transformation project.

As it transpires, Mr. Mersi, who is currently the CEO at the Ministry of Transport was a Deputy Commissioner at Inland Revenue at the start of the Business Transformation Project back in 2012. And prior to that he also spent some time at Treasury where he was the Deputy Secretary, Regulatory and Tax Policy branch.

So, although he’s coming from a Ministry of Transport background, Inland Revenue is not unfamiliar territory for him. It will be interesting to see how the organisation develops under his direction and governance of whichever hue will want to cash in on the benefits of the Business Transformation project.

And of course, one of the areas that he and the department will be involved in will be the implementation of law changes such as the proposed GloBE rules we’ve been talking about. And one thing he will need to ensure alongside the Minister of Revenue is that the Department continues to remain adequately funded. And I point to the troubles of the United States Internal Revenue Service, which has had its problems with enforcing the controversial FATCA rules which I mentioned a couple of weeks back.

It seems from another report from the United States Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, that the IRS is struggling with funding and its enforcement is falling off as a result. This led the Inspector General to comment. “The trending decline in enforcement activity is likely causing growth in the overall Tax Gap as taxpayers are less likely to be subject to an examination.”

The numbers of what the IRS call examinations, what Inland Revenue terms risk reviews, have fallen by between 55% and nearly 60% in the past five fiscal years. It bears to keep in mind that our IRD is actually a very efficient organisation, which, to borrow a phrase, you mis-underestimate at your peril. But as the example of the IRS shows, if funding falls away the opportunity opens up for the unscrupulous to evade tax.

‘Consulting’ on WfF

There’s a lot going on at the moment, partly because we are in the run up to the Budget next week. Something that’s been underway is for a few weeks now is a public consultation on Working for Families tax credits. This is being handled by the Ministry of Social Development and Inland Revenue. It’s part of a government review of working for families.

It’s interesting to look at what we’re being asked here compared with a typical Inland Revenue consultation, which has a lot more detail and is quite focussed.

The basic question that’s been posted is what do you like about Working for Families? Is there anything you want, don’t want changed? How do you think it can better support low income working families, families changing hours shift, working part time hours and those with care arrangements? What concerns do you have? And if you could change one thing about working families, what would it be? Now those are a set of questions are really not directed at professionals, but I hope that it gets a lot of good buy-in from the public.

In relation to concerns which I would raise one would be about how accessible it is. As my colleague, Professor Susan St Jones has pointed out, the in-work tax credits are a problem because they’re not available to everyone. And then there is the abatement rates and the resulting very high effective marginal tax rates which people on Working for Families suffer. They actually have the highest effective marginal tax rate of any taxpayer in the country. So those are areas where I think should be the focus for improvement.

Tinkering with WfF

Speaking of Working for Families, the Budget is next week, and I expect that there will be some tinkering going on with Working for Families based around the background papers to the consultation. They seem to be pointing towards an increase in payments being announced or being implemented in the Budget. Of course, with the cost-of-living issue, the Government probably will be keen to do something on that matter.

New Zealand budgets are actually really quite boring from a tax perspective. They’re not like budgets I used to see in Britain, for example, where tax measures came out from left field and were not always very coherent in what they’re trying to do. They certainly contained a lot of tinkering which kept us on our toes.

We’re not likely to see much like that next week. Bill English was one for sneaking in quiet tax increases or changes such as imposing employee contribution superannuation tax on KiwiSaver employer contributions, or withdrawing smaller allowances that were meant for children, the so-called “Paper-boy tax”.

One tax issue which has been hammered away at in recent weeks is fact that the tax thresholds have not been increased or adjusted since 2010. Eric Crampton of the New Zealand Initiative had a look at this. He considered what had gone on with the thresholds and where as a result the average tax burden had shifted. He made some educated guesses as to where those thresholds should be now.

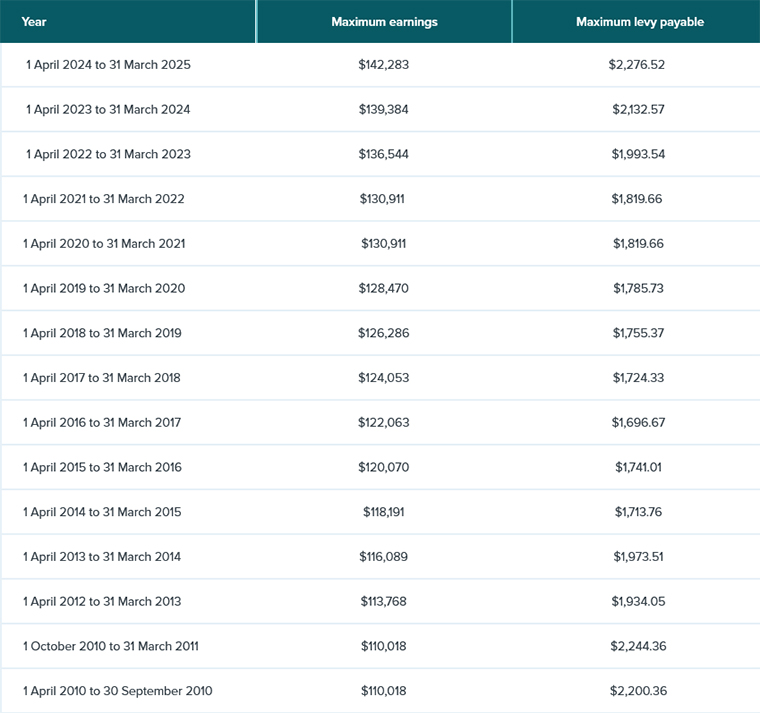

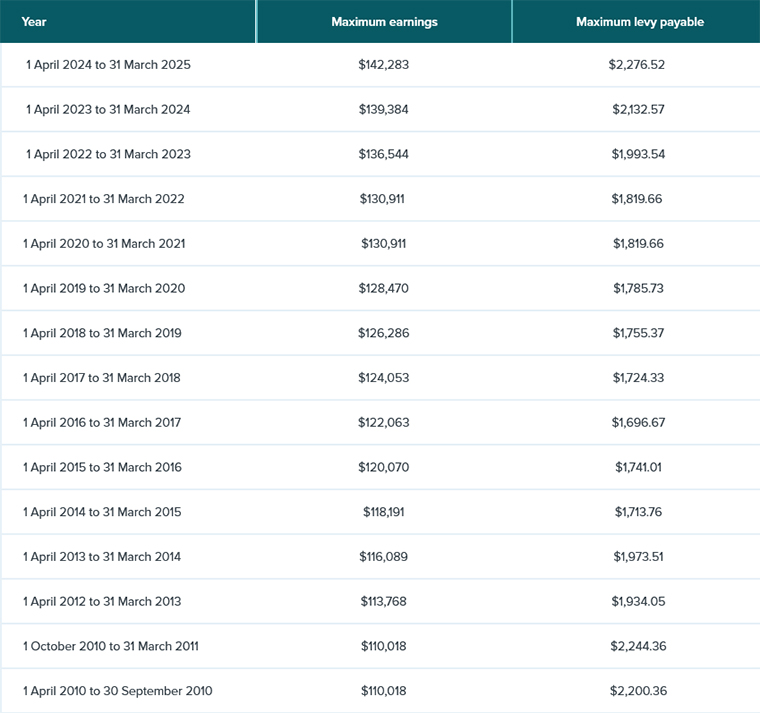

But there is actually some information floating around which would give us a more reasonable direction of what the thresholds should be if they had tracked along with inflation. These are the ACC thresholds for the upper limit of earnings on which the maximum 80% of income that may be paid out under a claim is based.

Back in 2010, when income tax rates were last adjusted, the ACC threshold was $110,018. As of 1st of April this year, it’s now $136,544. And so that increase over time over the period represents just over 24.1%.

So if you applied that 24% increase to the tax thresholds, this would be the position

| Tax rate |

Current thresholds |

Adjusted thresholds |

| 10.5% |

$0-$14,000 |

$0-$17,375 |

| 17.5% |

$14,001-$48,000 |

$17,376-$59,573 |

| 30% |

$48,001-$70,000 |

$59,574-$86,870 |

| 33% |

$70,000-$180,000 |

$86,871-$180,000 |

| 39% |

>$180,000 |

$180,000 |

(Note I’ve not adjusted the $180,000 threshold as it has only been in effect since 1 April 2021).

So that gives you some indication of what’s been going on. I think Governments of both sides have been, quite frankly, underhand in not adjusting for inflation. It isn’t just the tax thresholds, they’ve also done it in their other areas, such as Working for Families, where the threshold for abatement kicking in at $42,700, which is well below the $59,500 odd I suggested would be the upper limit to the 17.5% threshold. It will be interesting to see if anything is said or done about tax thresholds next week, but it’s a point that will certainly be addressed one way or another before next year’s election.

Talking of inflation, Inland Revenue has released a CPI adjustment to the square metre rate for dual use premises. This is where you can base a deduction for home office on a square metre rate. This has been set for the year ended 31st March 2022 at $47.85, which has been adjusted for 6.9% inflation in the 12 months to March 2022. So that’s a little useful thing to keep in mind when you’re preparing tax returns for clients who work from home or have a home office.

Rich entertainers avoiding tax

And finally, what have the Rolling Stones got to do with tax? Well, apparently this week is the 50th anniversary of the release of their magnum opus, Exile on Main Street. And the title is a deliberate reference to the fact that the Rolling Stones in 1971 decamped to the south of France because they were in trouble with UK tax authorities and facing very significant tax bills. At that stage, tax rates in the UK in some cases topped out at 98%.

So they went to France to record this album which is regarded by many as their creative peak. There’s a great story in The Guardian about what happened, including this fantastic quote ‘People took so many drugs, they forgot they played on it’.

Tax troubles and musicians go hand in hand. There are plenty of stories about various musicians and actors who’ve got themselves into terrible trouble with tax authorities and either finished up in jail, such as Wesley Snipes, or decamped elsewhere, like the Rolling Stones.

Well, that’s all for this week I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

9 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Inland Revenue gets ready for tax filing season and puts recipients of COVID-19 support payments under the microscope

- Insights into the composition of the Top 0.1%

Transcript

Inland Revenue is currently gearing up to begin processing 31st March 2022 year-end tax returns and personal tax summaries. Starting later this month it will be issuing automatic income tax assessments for most New Zealanders. But in preparation for that it has been giving updates to tax intermediaries on particular matters of interest. And a couple of notifications in the latest release caught my eye.

Firstly, there is form IR833 bright-line residential property sale information return which is required to be completed whenever a transaction which is subject to the bright-line test has taken place during the tax year. What Inland Revenue is saying is the form will pop up in a client’s return if it thinks the client has made a bright-line sale. And it will also pre-populate the information on the form, including the title number, address, date of purchase and date of sale.

This illustrates something we’ve spoken about many times, the level of information that’s available to Inland Revenue. It’s actually very good, in my view, that Inland Revenue is proactively putting in this information and saying, “Well, we know this.” I am aware that a few tax agent colleagues have had some very interesting discussions with clients where this notification has popped up and it’s the first the accountant or tax agent has heard about the matter.

As of last income year, all portfolio investment entity (PIE) income must be included in individual income tax return. Inland Revenue will pre-populate returns with the relevant data but not all returns will contain all the PIE information until after the PIE reconciliation returns and filed on or before 16th May.

In the meantime, Inland Revenue has reminded tax agents about this and advised not to file March 2022 tax returns either through Inland Revenue’s myIR or other tax return software until after that date unless you know for certain that the client is not a KiwiSaver member and does not have any other PIE income. That’s something to keep in mind because I’m sure some tax agents will be under pressure from clients who think that they are due a refund but haven’t factored PIE income into the equation.

What’s also going into tax returns is details of payments received under the Wage Subsidy Scheme, Leave Support Scheme and Short-Term Absence Payments. All these are what are termed reportable income. Consequently, tax returns will be required to be filed by recipients and there is going to be an information request in relation to these as part of the tax returns. Yet again, this is another example of how MSD and Inland Revenue shared the relevant information.

Inland Revenue administers the highly successful Small Business Cashflow Scheme which gave out loans to small businesses at the start of the pandemic. The initial two-year interest free period is now expiring for some businesses so repayments will be required to start shortly.

Talking about COVID-19 support, the numbers involved were quite extraordinary: apparently MSD has so far paid out $19.28 billion in the various subsidies and leave support payments. And Inland Revenue has paid out another $3.95 billion including Resurgence Support Payments and COVID-19 Support Payments.

The Resurgence Support and COVID Support payments were paid to businesses to help them pay business costs and therefore GST output tax is required to be returned on those receipts. Where the funds are used on relevant expenditure GST input tax credits may be claimed.

Inland Revenue has started checking that those who claimed the support payments were entitled to do so and assuming they passed that hurdle, they then applied the expenditure as was intended, i.e. business expenses. And I’m hearing stories from tax agents of very thorough investigations combing through the bank accounts of the businesses and individuals who received these payments. Some have resulted in “Please explain” enquiries coming back where apparently personal expenditure has been identified such as in one case where an EFTPOS payment for McDonald’s was identified.

This is yet another warning for those who applied for COVID support payments they either weren’t entitled to or misapplied the payments that they may find themselves under the gun from Inland Revenue. So far Inland Revenue have decided to proceed with 15 criminal charges and court proceedings are already underway for seven. In addition, as a result of investigations and some self-reviews the repayments made to date to MSD are over $794 million. ,

All of this is a timely reminder that with things calming down a little bit and so coming back to a stability, Inland Revenue is now applying itself back to its core business activities of investigations and reviews. Expect to see more news of these reviews and I think we may see one or two interesting cases emerge.

What Parker means

Moving on, last week’s speech by the Minster of Revenue David Parker quite predictably caused a stir and there was plenty of politicking over whether or not the proposal would lead to the introduction of wealth tax at some point and whether the Prime Minister would stand by her comments it wasn’t going to happen, the usual politicking etc. etc.

Subsequently, last Sunday I appeared together with Jenée Tibshraeny of www.interest.co.nz on TVNZ Q&A to discuss the implications of Mr. Parker’s speech. Off-air Jenée made a point echoed by several colleagues commenting on a LinkedIn post that the Tax Principles Act, if enacted, would work both ways. It wasn’t just a tool for saying, “Well, we need to introduce a particular type of tax.” It could equally stop a government introducing changes because it contradicted the agreed principles.

It’s a very valid point and it’s actually one of the sources of disagreement with the introduction of the 39% tax rate, because it affects the integrity of the tax system and the idea of administrative efficiency. Furthermore, it could apply to the measures relating to personal services, income attribution, which also I discussed last week. The argument here is that these rules would breach potential principles of horizontal equity, in that people earning similar amounts, may pay different rates of tax because of variations in the tax treatment.

Under the microscope

Other interesting insights have emerged in the wake of the speech. The Revenue Minister pointed to the lack of information about the high wealth individuals which prompted the research project into high wealth individuals would have caused some controversy. And earlier this week journalist Thomas Coughlan in the New Zealand Herald commented on an interesting briefing note about the project he’d obtained under the Official Information Act.

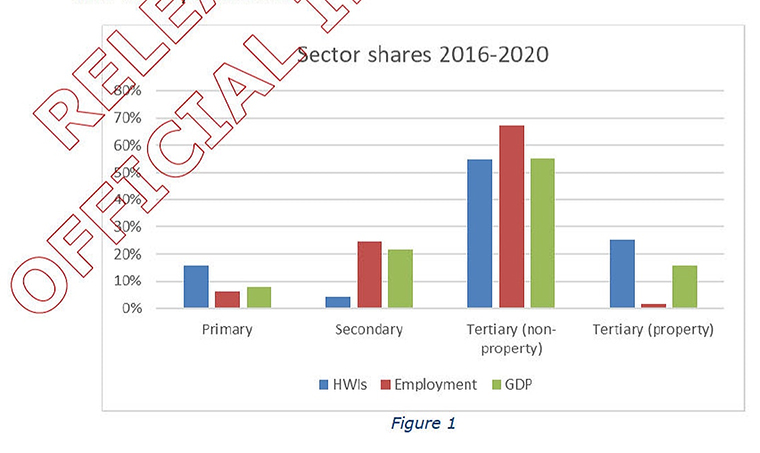

The briefing note looked into the representativeness of the wealth project population, and whether the high wealth research project population effectively represented the 0.1% of the wealth distribution of the population and the economic sectors they operated.

The note explains that the group that was selected for the project was based on

…environmental scanning undertaken by Inland Revenue over the past 20 plus years. This environmental scanning involved monitoring large transactions or other indications that individuals had significant wealth holdings using both public information and the department’s tax data. …

The briefing notes the selection is non-random and it is not expected to be representative of the population of all high wealth individuals. It is therefore quite possible that there may be high wealth individuals missing from the group “and there is no way to definitively state that the selected group is representative of the top 0.1% of the wealth distribution.”

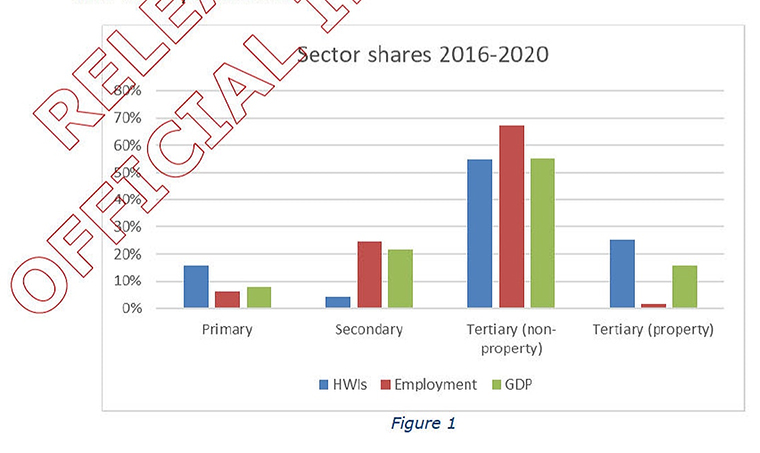

Having included that caveat, the note had some interesting analysis of what they had found so far. And it had a diagram comparing the share of GDP and employment to the main activities of high wealth individuals on the basis that you could reasonably expect the share of the industries represented by the individuals to be broadly similar to the spread of industries and activities in the New Zealand economy.

But it turns out that wasn’t the case. And in particular, relative to employment and GDP shares, the property and primary sectors are disproportionately represented in this project. The number of high wealth individuals in the primary sector is approximately 15%, even though the sector represents less than 10% of GDP. In relation to the property sector the proportion of high wealth individuals is 25%, compared with approximately 15% of GDP.

However, as the briefing note commented, there are clear reasons why there is this discrepancy “…there are certain activities (investment, property ownership) that would be expected to have greater involvement by those accumulate significant wealth….”

Incidentally, the primary sector and particularly the property sector, are sectors where existing tax rules such as the Bright-line test and the associated person rules work already to tax capital transactions. So that’s another reason why Inland Revenue may have better data on this particular group of wealthy individuals than others that work in the service economy.

Anyway, it will be interesting to see what further insights emerge from this high wealth research project. Meantime, no doubt the debate over how that data may be applied and the question of the taxation of capital and wealth will continue to rage, particularly in the run up to next year’s election.

Getting ready for tax filing season

And lastly this week, the final instalment of Provisional tax for those with a 31st March year-end is due on Monday. The key point here is taxpayers whose residual income tax liability for the year is expected to exceed $60,000, should ensure that they pay sufficient provisional tax to cover that total liability for the year. Otherwise, use of money interest, which is increasing to 7.28%, will start accruing together with potential late payment penalties.

As always, if taxpayers are struggling to meet payments in full, then either contact Inland Revenue to let them know and start to arrange an instalment plan. You will find that they are generally cooperative on this. Alternatively, consider making use of tax pooling to mitigate the potential use of money, interest and late payment penalties.

Well, that’s all for this week I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

2 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Minister of Revenue philosophises on tax and proposes a Tax Principles Act

- The IRS drops the ball

Transcript

Ministers of Revenue typically deliver several speeches during the year, mostly to business audiences or at the start of tax conferences.

On Tuesday, however, the Minister of Revenue, David Parker, delivered a speech at Victoria University Wellington entitled Shining a Light on Fairness in the Tax System, which is without doubt one of the most interesting speeches made by any Minister of Revenue in many years.

After some scene setting about the purpose of tax and how the Government has been able to use tax revenues to fund its COVID 19 response, Parker then pivoted to talk about beginning what he called a fact-based discussion. He started by challenging the assumption that our tax system is progressive overall.

“What’s hidden that the effective marginal tax rate for middle income Kiwis is generally higher than it is for their wealthiest citizens. Indeed, some of their wealthier Kiwi compatriots pay very low rates of tax on most of their income.”

The Minister then dived into the question of the lack of data on the distribution of wealth and capital income in New Zealand. He highlighted the fact that according to the Household Economic Survey, the highest net worth ever reported was $20 million.

This was, he said, ridiculous, given that we know there are billionaires in the country. As he pointed out, that meant the National Business Review’s annual rich list is a better set of data than the official statistics. In fact, that’s quite common around the world as statistics on capital wealth are rare and rich lists are often used to help revenue authorities gather data in this area.

So this lack of data, Parker explained, was the rationale behind the powers granted to Inland Revenue for the purposes of conducting research into high wealth individuals. As listeners will know, this is a somewhat controversial project, even though the Minister repeatedly stated that the intent was to gather better data for research and not as had been accused, so Inland Revenue could secretly work on new taxes.

“Until we have a much more accurate picture about how much tax the very wealthy pay relative to their full “economic income”, we can’t really we can’t honestly say that our tax system is fair.” And this led on to the most surprising part of the speech his proposal for a Tax Principles Act.

He referenced four principles of taxation that Adam Smith set out in Wealth of Nations back in 1776. And he noted that the many tax working groups and other reports that New Zealand has had over the past 40 years, such as the McCaw Review in 1982, the MacLeod Review in 2001, the most recent tax working group, and the all the work that went on during the Rogernomics period all basically followed these four principles set out by Adam Smith.

“They all endorse the same principles, based in that most core value of New Zealand – fairness. The main settled principles are:

Horizontal equity, so that those in equivalent economic positions should pay the same amount of tax

Vertical equity, including some degree of overall progressivity in the rate of tax paid

Administrative efficiency, for both taxpayers and Inland Revenue

The minimisation of tax induced distortions to investment and the economy.”

He also noted that recent reviews in the UK and in Australia both adopted similar approaches. Incidentally and perhaps not coincidentally here, Deborah Russell and I adopted the same principles when we wrote Tax and Fairness back in 2017.

And as you know, Deborah is now the Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Revenue and David Parker’s number two. The proposal is that officials should periodically report to ministers on the operation of the tax system using the principles as the basis for the reporting.

The Tax Principles Act would sit alongside existing legislation, such as the Public Finance and Child Poverty Reductions Acts, which also require the Government and officials to report on specific issues. This is quite revolutionary, but in a way sits within the philosophy of open tax policy that New Zealand has adopted through what we call our generic tax policy process.

This open approach to developing tax policy is widely regarded as world leading by other jurisdictions. The proposed Tax Principles Act is not inconsistent with the existing approach. The intention is there will be consultation later this year and following that a bill would be introduced once the principles had been agreed and the reporting requirements had been established.

The resulting bill would be enacted before the end of the current parliamentary term, i.e. just in time for next year’s election. The proposal caused quite a stir and there’s plenty of good reading on it. Bernard Hickey has a very good summary of the matter.

It’s also quite rare certainly to see Ministers of Revenue philosophise in quite a public way. David Parker referenced Thomas Piketty’s seminal work, Capital in the 21st Century. He also acknowledged the very regressive nature of GST. Somewhat controversially he noted that because GST in transactions between GST registered businesses essentially zeros out and is a final tax for those who are not GST registered, it many ways it falls on labour earners.

As he put it, “GST is really paid out of our earnings when we spend it. In economic terms, GST is mainly a tax on labour income. Who pays that cost?”

The Minister noted we have limited data on the overall rate of GST paid by New Zealanders, either by income or wealth decile. So he’s asked Inland Revenue to gather data and to provide feedback on this. I suppose from a political viewpoint this hints that potentially if there are changes to a tax mix at a later date, something may be done in relation to GST as it impacts lower income earners.

All this kicked up quite a stir. When I appeared on Radio New Zealand’s the Panel following the speech, the panellists expressed some shock about the fact that we don’t really have data about how wealthy people are. I think the reason for this, which wasn’t discussed by Minister Parker, is that it’s probably largely the unintended consequences of the abolition of stamp duties, estate and gift duties, and the absence of a general capital gains tax.

In other jurisdictions which have some or all of those taxes, this gives a reference point when a transaction occurs as to what wealth is held and by whom. Incidentally, the disclosure requirements regarding trusts I discussed last week although they are primarily an integrity measure, they also represent, in part, an attempt to gather some data about wealth held in trusts and help fill the gaps in Inland Revenue knowledge.

With National and Act already putting out their tax proposals, it looks like tax will feature quite heavily in next year’s election. So it’s very much a case of let’s watch this space.

Moving on, today is the due date for submissions on Inland Revenue’s discussion document, Dividend Integrity and Personal Services Income Attribution. This contains a couple of controversial proposals.

Firstly, that sales and share of shares in a company with undistributed retained earnings would trigger a deemed dividend.

And secondly, changes to the personal services income attribution rules, which would mean more income would be attributed to a primary income earner.

Now, neither of these proposals have gone down particularly well and to describe them as controversial would be a bit of an understatement. The personal services attribution rules, in fact, may well have a very much wider effect politically than the Government might want to see.

Brian Fallow, writing in a very good column in last week’s New Zealand Herald, pointed out that the attribution rules, if enacted, would affect very large numbers of small businesses quoting former Inland Revenue Commissioner Robin Oliver “It is likely to catch tradies — a plumber, say, or a landscape contractor — with a van and some equipment and just themselves or one employee doing the work,”

And Oliver raised the question, is this really appropriate? I expect a lot of submissions on this paper, and I urge you to do so because as you can gather from comments made by Oliver, it could have a quite potentially significant impact for the SME sector.

I personally think the proposals go too far. And incidentally, one of the reasons that the proposals have been made comes back to a longstanding topic in this podcast and something that wasn’t directly referenced by Minister Parker in his speech, the absence of a general capital gains tax.

Inland Revenue proposes any transfer of shares by a controlling shareholder to trigger a dividend where the company has retained earnings. In jurisdictions which have capital gains tax, that transaction is normally picked up as a capital gain. But as we don’t have a capital gains tax Inland Revenue is proposing a workaround which I don’t think is appropriate one.

I think there are other alternatives they might want to consider. The proposals on the personal services attribution rules are an integrity measure. They build on the Penny Hooper decision relating to surgeons from ten years ago.

They are understandable, but I believe go too far and are probably targeting the wrong group of people. Moving on Inland Revenue has a useful draft interpretation statement out considering what is the meaning of building for the purpose of being able to claim depreciation.

This has actually become quite relevant because back in 2011 the depreciation rate on buildings was reduced to zero. But in 2020, in the wake of the pandemic, the depreciation rate for long life non-residential buildings was increased from 0% to 2% if you use a diminishing value basis or 1.5% if you’re using straight line method.

What this draft interpretation statement explains is the critical difference between residential and non-residential buildings. it replaces a previous interpretation statement released in 2010 which has had to be updated following an important tax case in 2019 involving Mercury Energy.

A building owner will be able to claim depreciation for a ‘non-residential building’ and that can in some cases have some residential purposes. Generally, it’s aimed at commercial industrial buildings and certain buildings such as hotels, motels that could provide residential commercial accommodation on a commercial scale. It’s a useful explanation and comments on the draft close on 2nd May.

Chump change for FATCA

And finally, a quite extraordinary story from the United States, where it has emerged that a very important tax act, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, better known as FATCA, hasn’t generated as much income as was expected when it was introduced in 2010.

The projection was that over the ten years to 2020, it would raise about US$8.7 billion US. The US equivalent of Inland Revenue, the Internal Revenue Service, (the IRS) spent US$574 million implementing FATCA. But according to a report just released, all the IRS can show for all that money invested are penalties totalling just US$14 million.

Now, that’s quite extraordinary. And this is important from a New Zealand perspective, because FATCA represents a huge compliance burden for all US citizens who are required to file tax returns, even if they may be tax resident in another jurisdiction.

FATCA was the template for what became the Global Common Reporting Standards on the Automatic Exchange of Information. The rest of the world looked at FATCA and thought, “That’s a good idea. We’d like to have some information about what overseas accounts our taxpayers have”. And so, the CRS, as it’s known, was introduced and has been in force now for about four years.

I would hazard a guess that Inland Revenue probably gathered well in excess of US$14 million as a result of the introduction of CRS. But to come back to a point that David Parker made about politics and tax being inseparable. One of the reasons that the IRS has done so badly is that the Republican controlled Congress won’t give it the money to do its job. And that situation doesn’t look likely to change.

As David Parker said, politics and tax are inseparable. And we’re going to hear plenty more about the two in coming months.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

26 Apr, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Higher interest rates on unpaid tax

- Extended reporting requirements for trusts

- The potential New Zealand tax implications of a British political scandal

The Official Cash Rate was increased last week, but Inland Revenue seems to have pre-empted the effects of an increase as two weeks ago it announced that the interest rate for use of money interest on unpaid tax and for the prescribed rate of interest for fringe benefit tax purposes would increase from 10th May.

The use of money interest rate on unpaid tax will rise from 7% to 7.28%, and the prescribed rate of interest for fringe benefit tax purposes will rise from 4.5% to 4.7%, with effect from the quarter beginning 1st July 2022. The use of money interest rate for overpaid tax remains at zero.

With the final provisional tax payment for the March 2022 income year coming up on 9th May, it’s a good time to ensure that your Provisional Tax payments are as accurate as possible to minimise the effect of this use of money interest. That’s particularly true where a taxpayer’s residual income tax for the year is expected to exceed $60,000. So right now, advisers like myself are looking at this situation and making sure clients are getting ready to make the payments they need to minimise any potential interest charge.

As we’ve discussed previously tax pooling is a useful tool in dealing with tax payments. And right now, people are making use of tax pooling not only to get ready for the Provisional Tax payment coming up, but we’re also wrapping up the final tax payments due for the year ended 31 March 2021. There will be people who haven’t paid sufficient tax for the year and could be looking at substantial use of money interest and maybe even related late payment penalties.

This is therefore a good time to make use of tax pooling intermediaries. Typically, the deadline for making a request to use tax pooling is 76 days after the terminal tax date for the relevant taxpayer. If the taxpayer has a 31 March balance date and is linked to a tax agent, that is typically 7th of April, which means that sometime in mid-June is the final date for payment. If they’re not linked to a tax agent the terminal tax due date was on 7th February and therefore they’ve only got a few days left to make that payment using tax pooling.

What’s happened is that in the wake of the Omicron wave, Inland Revenue have used the discretion that was given to them when the pandemic broke out to extend the deadline for the time in which a request for making tax pooling can be made.

That time has now been extended to the earlier of 183 days after a terminal tax date or 30th September this year.

There are a few conditions. The contract must be put in place with the tax pooling intermediary on or before 21st June. Furthermore in the period between July 2021 and February 2022, the so-called affected period, the taxpayer’s business must have experienced a significant decline in actual predicted revenue as a result of the pandemic. This meant they were unable to either satisfy their existing commercial contract with tax pooling intermediary or weren’t able to enter into one, or they’ve had difficulties finding the tax return because either they or their tax advisor was sick with COVID.

Now this is a good use of the discretion available to Inland Revenue. But remember, it is COVID 19 related. So if you just happen to have been caught off guard and didn’t make your payments on time, you’re not going to get this additional extension of time. Tax pooling is a very useful tool which you should make use if you can.

But if you can’t, talk to Inland Revenue and make them aware that you have issues. You’ll find that they are more approachable in this than people might expect and can be quite fair so long as you come to the table with a reasonable offer.

Trust compliance just got more expensive

Moving on, we’re now starting to prepare tax returns for the year ended 31 March 2022. And for this year, the required reporting requirements for domestic trusts have been greatly increased following a legislative change last year.

In connection with that, Inland Revenue has released Operational Statement OS22/02, setting out the new reporting requirements for domestic trusts. These reporting requirements were introduced to gather further information from trustees so Inland Revenue can “gain an insight into whether the top personal tax rate of 39% is working effectively and to provide better information and understand and monitor the use of trust structures and entities by trustees”. It’s what we call an integrity measure.

There is a hook in that the legislation is also retrospective as it enables Inland Revenue to request information going back as far as the start of the 2014-15 income year.

The Operational Statement is a pretty detailed document, setting out over 48 pages the obligations involved. There’s a very useful flow chart on page 6 setting out what trusts will be caught under the provision and required to make the relevant disclosure disclosures. The basic rule is that all trustees of a trust, other than a non-active complying trust, who derive assessable income for tax year must file a tax return and therefore will be subject to the reporting requirements.

Non-active complying trusts are not required to file tax returns. These are trusts receiving minimal income under $200 a year in interest, no deductions other than reasonable professional fees to administer the trust and minimal administration costs, such as bank fees totalling less than $200 for the year. Such trusts are not required to file tax return.

The trustees also need to file a declaration that it is a non-active complying trust, it’s not enough to be not required to file a tax return, it must also file this declaration. The types of trusts covered by this exemption are ones which may hold a bank account earning some interest. More generally, their principal asset is the family home and the beneficiaries are living in that place and are responsible for meeting the ongoing expenses.

For those trusts required to comply there’s a fair bit of detail involved. But fortunately, there is an option for what they call Simplified Reporting Trusts. These are trusts which derive assessable income of less than $100,000 or deductible expenditure, which is also less than $100,000 and the total assets within the trust at the end of the income year are under $5 million. Such trusts can use cash basis accounting and aren’t subject to the full accrual reporting requirements set out by the Operational Statement.

In addition to preparing detailed financial statements, there are several other requirements that the trustees are expected to provide to Inland Revenue. These include details of each settlor of the trust and each settlement made on the trust together with details of beneficiaries and distributions made to beneficiaries. The trustees must also provide details of who holds the power of appointment within the trust.

All this expands greatly the amount of reporting that trusts have to do now. And although typically you do see financial statements prepared for most trusts that do have to file tax returns, these requirements extend those reporting obligations. And I daresay many trustees aren’t going to be too happy about the increased costs that will come out of that.

And of course, we have this potential issue now, that Inland Revenue may request information going back as far as the start of the year ended 31 March 2015. There’s a fair bit of controversy around this measure which would certainly mean a lot more work for advisors and trustees.

A very British scandal that risks Kiwis

Now, over in the UK, the Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, the equivalent of Finance Minister Grant Robertson, is embroiled in a political scandal after it emerged that his wife, Akshata Murty, has been claiming non-domiciled status for UK tax purposes.

Non-domicile status means that a person’s foreign income and capital gains are generally not subject to UK income tax and capital gains tax unless they happen to be remitted to the UK. It so happens that Ms Murty’s father is the billionaire owner of an Indian IT company, and it’s estimated that she may have saved up to £20 million of UK income tax on dividends from her father’s company. Needless to say, it’s not a great look for Mr Sunak as the person responsible for managing the finances of the UK to find himself in that position.

But Ms Murty’s status as what is called a non-dom is actually quite common. Most New Zealanders living and working in the UK would qualify as non-doms and may be able to make use of this special status. The exemption is pretty generous. In fact, according to a University of Warwick research study, more than one in five top earning bankers in the UK has benefited from claiming non-dom status. Apparently a sizeable share of those earning more than £125,000 per annum have non-dom status. For example, one in six top earning sports and film stars living in the UK have claimed non-dom status. As these persons have got an average income of more than £2 million pounds per year it’s a pretty significant benefit.

Now what New Zealand advisers need to be watching out for is misunderstanding the complexity of these rules. It used to be the general rule that a non-dom’s income was not taxed in the UK if it wasn’t remitted to the UK. The opportunity was for New Zealand trusts to make distributions of income to UK resident beneficiaries, but never actually remit that income to the UK. Instead it stayed in a New Zealand bank account or some other non UK bank account and therefore wasn’t subject to UK tax rates, which could be as high as 45%. It also meant that the income distributed wasn’t taxed at the trustee rate of 33%, so it was a very nice, tax-efficient system.

However, the rules have been subject to a number of changes in past years, as political pressure has built on the question of whether these non-doms should get such generous tax treatment. I’ve seen a number of cases where advisers have continued to apply what they think the rules are, unaware that there have been significant changes to the use of non-dom rules and the remittance basis. They have therefore inadvertently created tax liabilities for not only for the UK resident beneficiary, but potentially also for the trust.

The UK has introduced a register of trusts and in some cases, New Zealand trusts may be required to be part of that register. Along with UK inheritance tax this is one of these ticking time bombs where there is a lot of people who don’t know what they don’t know and could be in for an unpleasant shock.

It’s also fairly highly likely in the wake of this political scandal that there may be more changes to come to the non-dom exemption so trustees with beneficiaries resident in the UK, should be very careful about making distributions to such beneficiaries in the mistaken belief they are trying to exploit a rule which has been amended. Generally speaking, the use of trusts in the UK and in particular distributions from foreign trusts to UK tax residents is a real minefield and great care is required to avoid potentially serious tax consequences.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time, kia kaha, stay strong.

11 Apr, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Comparing New Zealand’s taxation of property with other countries

- OECD heralds a clampdown on crypto assets

- Another warning from Inland Revenue about attempts to manipulate income to avoid the 39% tax rate

Transcript

In last week’s Sunday Star Times, Miriam Bell looked at the question of how New Zealand’s taxation of property compares with other jurisdictions.

In doing so, she spoke to myself, Robyn Walker of Deloitte, and John Cuthbertson, the tax director for Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand. We all gave differing takes on the position.

According to the OECD statistics, we are near the bottom end of the range as a percentage of GDP. Including local government rates, New Zealand’s taxes on property for 2020 was approximately 1.9% of GDP and the total tax take for the year of 32.18% of GDP. By comparison, Australia’s taxes on property was 2.718% of GDP (2019 numbers), the UK was 3.855% and Canada 4.15% of GDP (both 2020 numbers).

As you can see, Canada and the UK are significantly above New Zealand. One of the reasons for this, as Robyn and John pointed out, is that they have a range of stamp duties that may apply. But also, as we all pointed out, all three jurisdictions, Australia, Canada and the UK, also have capital gains tax and in the case of the UK, inheritance tax may also apply on some properties on transfer.

The article provoked a fairly lively debate, as you would expect. The range of views across the board is that, yes, it looks like we’re under taxed. But the bright-line test is in place which is problematic in that although it looks like a capital gains tax, it doesn’t apply comprehensively, unlike in the other three jurisdictions.

Robyn Walker then made a very good point following through that the design of the bright-line test is basically all or nothing. If you hold property for more than 10 years, you’re outside the test, which means that you’re likely not to be taxed on it. So you get this wide variance in the tax effect of sales or property, which you don’t see to the same extent in other jurisdictions.

Robyn subsequently did a nice little post on LinkedIn, in which she looked at what would be the tax consequences in Australia, Canada, the UK, and New Zealand for the sale of a property which realised a $100,000 gain. Because we treat it as income, we’ll tax the full gain at the relevant marginal rate and for the purpose of the example that was 33%. Canada and Australia will tax only half the gain at the relevant marginal rate, although non-residents in Australia will be taxed on the full gain. And although the UK will tax the full gain the top rate applicable is 28%.

The end result was that if the bright-line test applied, then the tax payable in New Zealand would be highest relative to the other three jurisdictions. But if the bright-line test didn’t apply, then it was the lowest. In fact, it would be nil. And this reinforces Robyn’s point that it is a poorly designed test which can be very unfair in its application. You hold a property for nine years and 363 days, you’re taxed. Hold it for 10 years and one day you’re probably not.

The point I stressed in the article is that we want to look at broadening the range of taxation, and it’s fair if we do so because we start to get round these arbitrary distinctions. As I’ve previously said, my preferred methodology for expanding the taxation of capital is that promoted by Associate Professor Susan St John and myself the fair economic return, not a transactional based capital gains tax.

Anyway, this debate will continue to run and run. Miriam Bell’s article provoked a fierce reaction on Stuff, unsurprisingly, and there’s been an interesting debate around Robyn’s LinkedIn article. I urge you to take a look at that.

I think we really do need to address the issue of taxing property particularly when you consider what the Infrastructure Commission said earlier this week about property owners benefiting to the extent of house prices being 69% higher than they would have been without actions being taken to restrict the supply of housing. Housing and the taxation of property is a touchpoint now and will be in next year’s election. We’re going to see plenty more of this debate

Taxes on crypto assets are coming

Moving on to another controversial asset class – crypto assets. Now the value of crypto assets has just simply exploded in the last 10 years. Because of the explosion of the value, it has forced its way onto the tax agenda and tax authorities all around the world are looking to see how this new asset class fits in with their existing rules. New Zealand is no different from other jurisdictions which are all struggling with this. The recent tax bill that was passed last week, by the way, had provisions relating to the application of GST on crypto-assets.

A couple of weeks back, the OECD released a public consultation document proposing a new tax transparency framework for crypto assets. What it has identified is that crypto assets can be transferred and held without going through the normal financial intermediaries, such as banks, and fund managers. And from a tax perspective, there’s no central administrator having what the OECD calls full visibility on either the transactions carried out or on the location of crypto asset holdings.

It also appears that malware attacks and ransomware attacks, payments are increasingly demanded in crypto-assets, which are largely untraceable. So that’s obviously a matter of concern to not just tax authorities.

The OECD paper also points out that some new paid payment products. Such as digital money products and central bank digital currencies, which also provide electronically storage and payment functions similar to money held in traditional bank accounts.

But at the moment, none of these are covered by the Common Reporting Standard on the Automatic Exchange of Information. A reminder the Common Reporting Standard is an agreement between almost 100 jurisdictions where they agree to swap information on financial accounts held in their country by citizens or tax residents of another jurisdiction. It’s been a huge step forward in tackling adn improving tax transparency and tackling tax evasion.

And what the OECD is proposing is, it wants to develop a new global tax transparency framework, which will involve the same reporting for transactions related to crypto assets as for financial assets covered by the Common Reporting Standard. And it’s calling this the Crypto Asset Reporting Framework, or CARF. The paper proposes that the following types of transactions involving crypto assets will be reportable under the CARF:

- exchanges between crypto assets and fiat currencies;

- exchanges between one or more forms of crypto assets;

- reportable retail payment transactions; and

- transfers of crypto assets.

This would bring about a very significant change in the crypto asset world as a result. It will basically be bringing the whole crypto asset world in line with other reportable transactions under the existing Common Reporting Standard framework. I doubt that will be very popular with investors in the crypto world, but it certainly will be for tax authorities and other authorities, such as financial regulators and police, as they deal with the implications of the arrival of this asset class. Consultation is now open on the document through until 29th April.

Same old problem returns

And finally, this week, a couple of weeks ago I discussed the new Inland Revenue consultation paper on countering attempted top tax rate avoidance. It so happens that yesterday RNZ had a story on the paper and Inland Revenue’s concerns that “structures may be being used to reduce incomes below $180,000.”

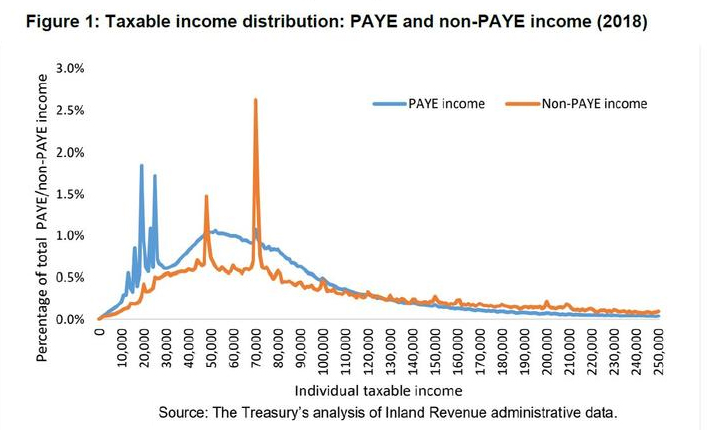

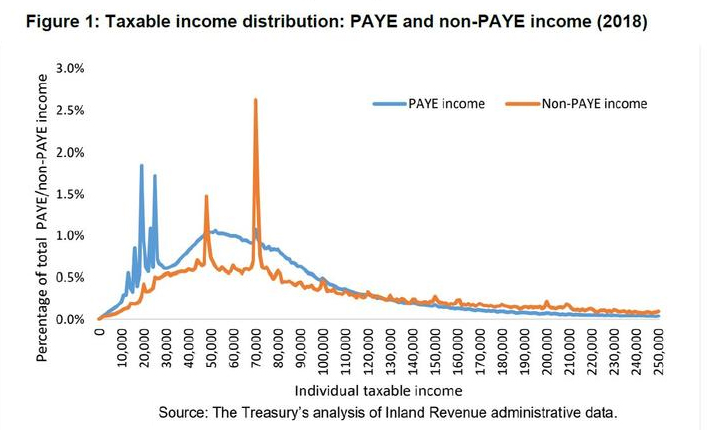

Inland Revenue has provisionally estimated that income from these high earners will be down $2.88 billion, or about 14% from the year prior. This is on the basis that the average self-employed person – who has the most control over their income – might declare 13% less income than they did the year before, to drop from $191,000 to $166,000 (and by happy coincidence below the $180,000 threshold). The number of PAYE earners is expected to reduce, and also declare lower incomes, from an average of $228,000 to $217,000.

If that is happening then I would expect Inland Revenue to react aggressively. On the other hand, Inland Revenue has known for some time that self-employed income spikes around the $48,000 mark (the threshold when the tax rate increases from 17.5% to 30% and $70,000 dollars when the threshold tax rate increases to 33%). I’m not yet aware of increased Inland Revenue investigation activity into such apparent income manipulation. It seems to me that although Inland Revenue has concerns about manipulation involving the new 39% tax rate, what appears to be happening around the $48,000 and $70,000 thresholds seems very blatant.

The RNZ report included a chart from Inland Revenue of the taxable income distribution for the 2018 income year which illustrated these spikes occurring at the $48,000 and $70,000 thresholds.

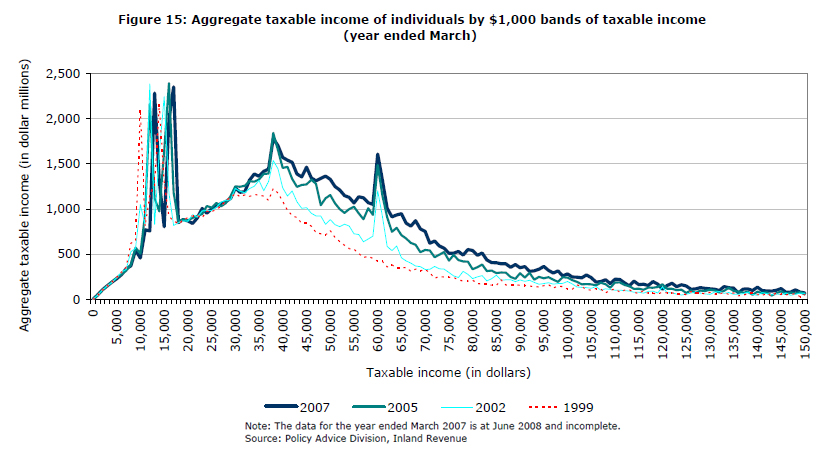

The graph mirrors one produced in 2008 (when the top tax rate was 39%). You can see exactly the same pattern of income spikes around $38,000, the threshold at which the tax rate increased from 19.5% to 33% and then at $60,000 when the tax rate rose from 33% to 39%.

In other words this is a very longstanding problem and the question arises why that issue has been allowed to continue? Does Inland Revenue have the resources to address it? They most certainly will say they do, and they would also probably say that they have had a lot to deal with managing the COVID-19 response over the last two together with finalising the Business Transformation project. Either way you should expect action on this from Inland Revenue.

Incidentally on the question of high tax rates, another news report covered the effect of increases for working for families tax credits. It pointed out that the effective marginal tax rate for recipients of working for families can in some cases be 57%. This is the combination of 30% tax rate on incomes over $48,000 and the 27 cents in the dollar abatement, which applies above a threshold of $42,700.

So before people start complaining about 39% being a very high tax rate, think about what’s going on with working for families, accommodation supplement and other social welfare payments. It’s quite conceivable that someone on $60,000 per annum, receiving working for families with a student loan could have a marginal tax rate on every dollar earned of 69%. This represents 30% income tax, 27 cents on the dollar abatement on their working for families and 12% student loan repayments.

By the way, the $42,700 threshold when the working for families’ abatement kicks in is now, by my calculations, less than the annual income of someone working 40 hours a week on the current minimum wage would earn. It’s another case of where governments have allowed inflation to quietly increase the tax take with worse consequences for people at the lower end of the scale. Yet another issue we’ve talked about repeatedly.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time, kia kaha, stay strong.