The OECD proposes a crypto-asset reporting framework

- The OECD proposes a crypto-asset reporting framework

- New levy proposal for farmers’ greenhouse gas emissions;

- TOP’s bright idea about tax rate

Last week, the OECD launched its Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework (CARF). This is a response to a G20 request that the OECD develop a framework for the automatic exchange of information between countries on crypto-assets. In other words, it is going to be a development of the existing Common Reporting Standards on the Automatic Exchange of Information or CRS. The CARF was presented to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors for discussion at their meeting this week in Washington D.C.

The proposed rules cover four areas:

- the scope of crypto-assets to be covered,

- the entities and individuals subject to data collection and reporting requirements,

- the transactions subject to reporting as well as the information to be reported in respect of such transactions and

- the due diligence procedures to identify crypto-asset users and controlling persons and to determine the relevant tax jurisdictions for reporting and exchange purposes.

CARF is intended to complement the CRS and mean that crypto-assets will be subject to automatic exchange of information reporting. Now the reason that that has come up is unsurprising really. Individuals holding wallets which are not affiliated with any current financial institution or service provider, and are therefore then able to transfer crypto-assets across jurisdictions. As the OECD report notes:

“this presents the risk that relevant crypto-assets are used for illicit activities or to evade tax obligations. Overall, the characteristics of the crypto asset sector have reduced tax administrations visibility on tax relevant activities carried out within the sector, increasing the difficulty of verifying whether associated tax liabilities are appropriately reported and assessed”

This is a very long way of saying there’s probably a lot of tax evasion going on in the crypto-assets sector.

CARF is therefore an obvious response. It is also part of the huge ongoing trends in the modern tax world of the acceleration in reporting and exchange of information between jurisdictions. This is a very, very significant development in the tax world that happened in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis and has largely gone unreported in the wider press although it appears to be generally accepted by the public. When you align this alongside what’s happening with the Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals, then the days of tax havens where money can be parked outside the tax net of major jurisdictions, are numbered.

So what crypto assets are covered? Well, the definition is pretty broad, it targets assets “that can be held and transferred in a decentralised manner and without the intervention of traditional financial intermediaries”, i.e. banks and other financial institutions. This includes stablecoins, derivatives issued in the form of crypto-assets and certain nonfungible tokens.

There are three categories excluded from what’s termed “Relevant Crypto-Assets”:

- crypto assets, where have it’s been determined they cannot be used for payment or investment purposes,

- Central Bank Digital Currencies which represent a claim in Fiat Currency on an issuing Central Bank or monetary authority, which function similar to money held in a traditional bank account,

- Specified Electronic Money Products that represent a single Fiat Currency and are redeemable at any time in the same Fiat Currency. (Not sure I’ve encountered any of these myself, to be honest).

Reporting entities are any intermediary or service provider which is facilitating exchanges between relevant crypto-assets or between relevant crypto-assets and fiat currencies. Generally, they will be subject to the reporting requirements of the jurisdictions in which they are either tax resident or have a regular place of business or branch through which they carry out reportable transactions.

Keep in mind, CARF ties in with the CRS which is already hugely comprehensive and covers most of the main tax jurisdictions and tax havens. The ability for crypto asset service providers to slip out from underneath the CARF reporting requirements is going to be quite limited.

Three types of transactions are going to be reportable:

- exchanges between Relevant Crypto-Assets and fiat currencies,

- exchanges between one or more forms of Relevant Crypto-Assets, and

- transfers of Relevant Crypto-Assets.

CARF has been developed to sit alongside CRS and in fact at the same time the OECD carried out its first comprehensive review of the CRS regime. It’s proposing some amendments to bring new financial assets, products and intermediates within the scope of CRS. The changes are also being made to try and avoid duplicate reporting with that which is expected to happen under CARF.

The entire CARF framework runs to over 100 pages. It should be signed off subject to any further work requested by the Central Bank Governors and Finance Ministers at their meeting this week. There will no doubt be some further tweaking, so it’s not yet all set to go. No doubt there will also be some lobbying for changes in the regime.

CARF is, as I said earlier, part of a growing trend for international cooperation on the sharing of information. When implemented it basically will probably mark an end, or certainly a restriction, on the use of crypto assets for tax evasion and other nefarious purposes.

Making farms pay

On Tuesday, the Government released its proposals for how to price agricultural emissions.

These are in response to the recommendations earlier this year from He Weka Eke Noa, the Primary Sector Climate Action Partnership, for a farm level pricing system. The Climate Change Commission, He Pou a Rangi, also provided separate advice on agricultural emissions.

The Government’s proposals try and integrate what He Weka Eke Noa and He Pou a Rangi have suggested. The intention is to price agricultural emissions at the farm level. But it comes with a big stick – if the sector cannot reach agreement by 1st January 2025, then agricultural emissions will be be priced under the Emissions Trading Scheme.

The key part of the proposal is a farm level split gas levy to price agricultural gas emissions. It will apply to farmers and growers who are GST registered and meet certain livestock and fertiliser use thresholds. There would be separate levy prices set for long lived gases and biogenic methane and these will be set up after advice from the He Pou a Rangi and in consultation with the agricultural sector and iwi and Māori.

The long-lived gases (basically carbon) price will be set annually and then linked to the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme unit price. There’s a separate biogenic methane levy which will be adjusted based on progress towards domestic methane targets. One of the feedback matters the Government is seeking is whether that methane levy price should be reviewed annually or every three years.

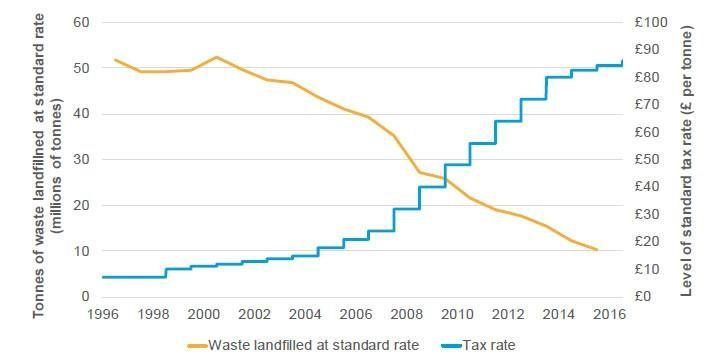

With regards to the revenue raised, the Government proposes it that the revenue is used to fund incentives and sequestration payments, with any remaining revenue to fund the administration of the pricing scheme and a joint government and Māori revenue recycling strategy. There’s a proposal for incentive payments for a range of on-farm emissions reduction technologies and practises. I fully endorse this policy of using funding from an environmental tax to help the transition.

But if you’ve been watching this, you’ll know it has taken a long time to get here. It’s almost 20 years since the infamous ‘Fart tax’ was first proposed and Shane Ardern MP drove a tractor up the steps of Parliament. So progress has been very slow on this, which I personally find very frustrating.

Here in the city, we need to be working on reducing our transport emissions. Rather ironically, on the same day of the Government announcement, Ruapehu Alpine Lifts went into voluntary administration. The ski field operation has clearly been affected not just by one very bad year and the effect of Covid. This is something that’s been building for some time.

We’ve also had the recent floods and damage reports coming out of Nelson where the insurance claims so far total $50 million. So change is happening all around us and my view is we are going to have to adjust to it and try and do something to reduce emissions as part of the global effort. We can’t rely on everyone else to do it for us.

TOP tackles tax bands

Finally, this week, there’s been a lot of talk about tax cuts ahead of next year’s General Election, particularly in the wake of the massive u-turn by the UK government over a proposed higher rate tax cut which has now resulted in the sacking of the Chancellor of the Exchequer (Finance Minister) Kwasi Kwarteng.

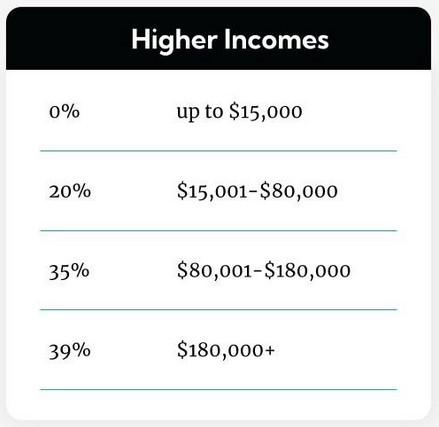

Amidst all of that chaos The Opportunities Party released its two-phase tax policy, phase one of which contains substantial tax cuts. But what caught my eye about TOP’s suggestion is their proposal to introduce a tax-free threshold of $15,000, together with adjusted tax thresholds.

Now tax-free thresholds are expensive, but they are seen around the world. Australia has one for the first A$18,200. The UK tax free personal allowance is £12,570 and America has a flat $12,000 exemption.

But what I thought is interesting about TOP’s proposal is they have looked at the question I’ve talked at length about what happens for low- and middle-income earners when their income crosses the current $48,000 threshold and the rate jumps from 17% to 30%. Under our current tax structure 12.5 percentage point jump is the highest such rate – the next jump at $70,000 is only from 30% to 33%.

So, I’ve been thinking for some time that we really ought to be looking at these thresholds and rate bands and maybe combining three into two, which is what TOP propose.

Now, TOP have got to either win an electorate or get across the 5% threshold before they’ll be in any position to propose their policy. (The second part of their policy would fund those tax cuts by a land value tax, which, of course, is longstanding TOP policy). We’ll have to wait and see until after next year’s election.

But if you want to hear more about what type of tax changes could happen and their implications then this week on RNZ’s The Detail podcast, Jenée Tibshraeny of the Herald and I spoke to Sharon Brettkelly about tax cuts here and in the UK, how our tax system works and what could be done if we’re helping people at the lower income level.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!