3 Feb, 2021 | Tax News

Terry Baucher looks at some of the taxation ramifications from the Climate Change Commission’s draft report

The Climate Change Commission released its draft advice for consultation on 31st January. What of note did it have to say about the role of taxation?

The Commission’s Necessary Action 3 recommended accelerating light electric vehicle (EV) uptake. As part of this it suggested the Government:

Evaluate how to use the tax system to incentivise EV uptake and discourage the purchase and continued operation of ICE [internal combustion engine] vehicles.

As the Commission is no doubt aware taxes can have significant behavioural changes very quickly as the following example of the changes in the United Kingdom’s Landfill Tax illustrates.

Between its introduction in 1996 and 2016 the rate of Landfill Tax was increased from just under £10 a tonne in 1996 to nearly £90 a tonne by 2016. Over that 20-year period the annual amount of waste landfill fell from 50 million tonnes to 10 million tonnes.

So what tax changes could be used to incentivise change?

The available evidence indicates that the present fringe benefit tax (FBT) rules are unintentionally environmentally harmful. A NZ Transport Agency report in 2012 examining the impact of company cars found they were heavier with higher engine ratings than cars registered privately. The availability of employer-provided parking encouraged longer commutes from more dispersed, automobile-dependent locations than would otherwise occur. Under present rules employer-provided parking is largely exempt from FBT.

The trend for larger, heavier vehicles has accelerated since 2012 with a greater preference for vehicles such as SUVs and utes. Last year 77% of all new passenger vehicle registrations were SUVs and utes.

A by-product of the trend for purchasing of twin-cab utes appears to be widespread non-compliance with the existing FBT rules. This is in part because of an incorrect perception that such vehicles automatically qualify for the “work-related vehicle” exemption from FBT. The combination of greater numbers of such vehicles and apparent under-enforcement of the FBT regime[1] exacerbates the trend for indirectly environmentally harmful practices identified by the NZTA in 2012.

Inland Revenue should therefore immediately increase its enforcement of the FBT rules relating to twin-cab utes. These changes should be allied with the adoption of the approach in Ireland and the United Kingdom where FBT is greater on higher emission vehicles. I consider these emission-based FBT rules can be adopted relatively quickly, and it ought to be possible to have these in place by 31st March 2023.

As an interim measure to encourage greater take up of EVs the Government could consider exempting EVs from FBT until the new emission-based FBT rules are in place. In Ireland, EVs with an original market value below €50,000 are presently exempt from FBT. The threshold here could be $50,000.

Additional FBT related measures include increasing the application of FBT on the provision of carparks to employees and not taxing the provision of public transport to employees. This reverses the present treatment and fits better with a policy of decarbonisation without impacting an employer’s ability to provide such benefits.

Taxing the provision of employer-provided carparks could raise significant funds. The 2012 NZTA report estimated the annual value of free parking in Auckland to be $2,725. With at least 24,000 employer owned car parks in the city this amounted to a tax-free benefit of $65 million per annum. FBT is generally charged at 49% of the value of the benefit so the potential FBT payable could be between $75 and $100 million per annum.

The suggested FBT changes should change behaviour, but as the Commission also pointed out we need to reduce emissions. We have one of the oldest vehicle fleets in the OECD and it is getting older. The average age of light vehicles in Aotearoa New Zealand increased from 11.8 years to 14.4 years between 2000 and 2017.[2] Compounding this issue, the turnover of the vehicle fleet is slow, on average vehicles are scrapped after 19 years (compared with about 14 years in the United Kingdom).

Furthermore, we are one of only three countries in the OECD without fuel efficiency standards. As a result the light vehicles entering Aotearoa New Zealand are more emissions-intensive than in most other developed countries. For example, across the top-selling 17 new light vehicle models, the most efficient variants available here have, on average, 21% higher emissions than their comparable variants in the United Kingdom. They are also less fuel efficient, burning more fuel and therefore generating higher emissions. The Ministry of Transport estimated if cars entering Aotearoa New Zealand were as fuel efficient as those entering the European Union, drivers would pay on average $794 less per year at the pump.

The Commission is concerned about the impact of its proposals on low-income families, who could be asked to bear a disproportionate part of the costs of change. For this reason, I suggest the funds raised from the FBT changes should be first applied to a vehicle exchange programme. This would remove older higher-emitting vehicles (say ten or more years old) by subsidising purchase of newer vehicles (maybe from car rental companies with excess stock).

If it seems counter-intuitive to subsidise “old carbon” technologies there are three short-term benefits to consider: newer cars generally have lower emissions, are more fuel efficient and are safer, indirectly helping reduce the road toll. This scheme also supports the most vulnerable families who cannot rely on public transport and are most likely have older, less fuel-efficient vehicles. Furthermore, funds involved would go further than if applied in directly subsidising the purchase of electric vehicles.

I also suggest the buy-back scheme is targeted at lower-income families and should therefore be means-tested. A starting threshold might be the Working for Families tax credits threshold of $42,700 above which abatement applies. This threshold could be increased if the vehicle is more than, say, 15 years old with accelerated rates applying if the car is more than 19 years old (i.e. older than the life expectancy of the average car in Aotearoa New Zealand).

The Commission has opened the debate on our transition to a greener, low-emissions economy. Tax will have a major role in that as Pascal Saint-Amans, the Director of the OECD’s Centre for Tax Policy and Administration acknowledged last year when he suggested that when responding to the impact of Covid-19.

Governments should seize the opportunity to build a greener, more inclusive and more resilient economy. Rather than simply returning to business as usual, the goal should be to “build back better” and address some of the structural weaknesses that the crisis has laid bare.

A central priority should be to accelerate environmental tax reform. Today, taxes on polluting fuels are nowhere near the levels needed to encourage a shift towards clean energy. Seventy percent of energy-related CO2 emissions from advanced and emerging economies are entirely untaxed and some of the most polluting fuels remain among the least taxed (OECD, 2019). Adjusting taxes, along with state subsidies and investment, will be unavoidable to curb carbon emissions.

The 2019 Tax Working Group (the TWG) chaired by Sir Michael Cullen undertook a review of environmental taxation and made several significant recommendations in its final report.

Unfortunately, the backlash against the TWG’s proposed capital gains tax meant that its commentary and proposals on environmental taxation were overlooked.

Nevertheless, the TWG’s groundwork in this area now needs to be built on. It’s therefore interesting to note that in its briefing to the new Minister of Revenue David Parker Inland Revenue noted one of its top tax policy priorities was “the role of environmental taxes and what an environmental tax framework should look like.”

Given that David Parker is also the Minister for the Environment I suggest Inland Revenue might be accelerating its work in this field, if the goals suggested by the Climate Change Commission are to be met. Watch this space.

[1] FBT is tied to employment. Over the 10 years to 30th June 2020 the amount of PAYE collected by Inland Revenue rose by almost 66% from $20.5 billion to $34 billion. However, over the same period the amount of FBT paid rose 28% from $462 million to $593 million. This gap suggests some level of under-reporting and enforcement.

[2] By comparison in the United States in 2016 it was 11.6 years for cars and light trucks and 10.1 years for all vehicles in Australia for the same year and 7.4 years for passenger cars in Europe in 2014 (Ministry of Transport data)

10 Aug, 2020 | The Week in Tax

- Fringe benefit tax

- How workable is the Greens Party’s wealth tax?

- Is unemployment insurance on the cards?

Transcript

The new car sales results in July turned out to be something of a surprise, with 8,400 new passenger vehicles sold, which was more than 3½% higher than the corresponding July last year. However, overall passenger new car sales are down 23% over the first seven months of July of this year, which makes July’s results seem very strong.

What caught my eye about these results was that SUVs represented 77% of the new cars sold in a month. That’s the highest ever. Sales of SUVs have been growing in popularity for a variety of reasons. And one particular subgroup which has had strong growth in sales is the twin cab ute.

This brings us back to the question of the fringe benefit treatment of twin cab utes. This is a topic which we’re going to hear plenty more about as Inland Revenue gets round to thinking ‘You know, maybe we might need to collect some tax to pay for all this support we’re providing to the economy’.

Fringe benefit tax (FBT) is calculated in one of two ways. You can either take 20% of the GST inclusive cost price and apply that to the vehicle, or you can take the motor vehicles tax value, which is the original cost less the total accumulated depreciation of the vehicle as at the start of the relevant FBT period. That latter option, the cost price, comes down to a minimum FBT value of $8,333. You then tax the resulting value at the FBT rate, which generally speaking is 49%.

Now, just as an aside, the SUVs represent very good value for money, particularly twin cab utes. For $30,000 you can get a reasonably well spec’d vehicle. And this is one of the problems with electric vehicles – which represent an insignificant amount of new car sales – is they’re expensive. Consequently, because they’re expensive and FBT is driven off the vehicle value, it means that unless a company has made a very big commitment to the use of electric or hybrid motor vehicles and imposes some fairly stringent rules around their private use, hefty FBT bills will ensue. So, this is a major disincentive for their purchase.

Coming back to twin cab utes, the myth has been around for quite some time that if properly sign-painted, they represent work related vehicles and are therefore exempt from FBT. There’s plenty of anecdotal evidence I’ve discussed before about widespread non-compliance or non application with the rules around work related vehicles.

Inland Revenue hasn’t said anything publicly about this although we understand in the background an initiative was under consideration, before COVID-19 rather took its eye off the ball.

But a key point, which people must understand, that if a vehicle is available for private use other than travel from home to work or incidental travel, then it is not a work related vehicle, even if it is sign-painted. It is therefore subject to FBT. This is the bit which I think is going to potentially trip up a lot of tradies and other users of twin cab utes. You have to make sure you are compliant with the FBT rules around private use, which are pretty stringent.

As I said, this is a matter that I have talked about beforehand. Inland Revenue’s tools for dealing with this are much stronger now because it actively searches social media. At one tax conference an Inland Revenue representative said that if it saw someone put a photo on Facebook about going fishing and showing the ute towing a boat, it would happily drop a quick message through the myIR system to the effect of ‘Hey, we see you’re enjoying your fishing. Did you make sure you complied with the FBT rules?’ That’s very Big Brotherish, but it’s what it can do.

And so, you can’t say you’ve not been warned. I expect that we will start to see a significant increase in Inland Revenue investigations of FBT for the work-related vehicle exemption and twin cab utes.

The Green Party wealth tax plan

Moving on now into the election season. And some of the parties have released their tax policies. Others will either not do so or have already made it clear, as National has, that they don’t propose tax cuts or tax increases.

But the Green Party came out and announced as part of their Poverty Action Plan, a proposed wealth tax of 1% on net worth above $1 million and 2% above $2 million dollars net worth. (This is per person, by the way.)

Writing this week in the Herald, former member of the Tax Working Group, Professor Craig Elliffe, took a look at the Greens policy.

He noted that when things settle down, there’s quite likely going to be a requirement for more taxes to pay down some of the government indebtedness. And noting that the Tax Working Group itself had suggested that the tax system needed to look at the taxation of wealth and capital, Professor Elliffe then looked into the Greens’ proposals and raised the question whether a wealth tax was the best form to deal with these issues. And his short answer was no.

The whole article is well worth reading. Professor Elliffe pointed out that wealth taxes have declined in use: 12 OECD countries had a wealth tax in 1990, but only three -Norway, Spain and Switzerland retain them now. Add in Argentina and we’re talking about only four countries of any substantial size having a net wealth tax. You do however, find plenty of transfer taxes, such as inheritance tax gift duties.

And most of the OECD members also have a capital gains tax, although Professor Elliffe, for fairly obvious reasons, shied away from mentioning that.

Wealth taxes don’t raise much revenue was another of his arguments. And then there’s the whole question about tax integrity. What would happen in terms of tax planning, if attempts were made to introduce a wealth tax? I think that’s a very valid concern.

He also raised the question of jurisdictional flight. People may move out of New Zealand and move assets into and out of New Zealand and try and attempt to limit the wealth tax. All that is perfectly valid. But I can’t help but wonder whether the days of tax havens sheltering vast amounts of wealth, trillions of dollars in fact, are actually numbered.

Every country around the world now faces major pressures on its balance sheet, with lower taxes and greatly increased debt. So I’m beginning to think that we may see, just as we did in the last 10 years with the introduction of the Common Reporting Standards on the

Automatic Exchange of Information, a concerted move to end tax havens.

And that won’t happen overnight because obviously there will be very significant interests pushing back against that. But governments will probably look at the issue and conclude we cannot have trillions of dollars of assets stashed away where we can’t tax it at a time of such severe strain on our finances.

Now, Craig Elliffe finishes his article by noting

In summary, there is likely to be a strong need for tax revenue and standing back from the New Zealand tax system the under-taxation of capital is an issue for the variety of reasons set out in the Tax Working Group’s interim and final reports. Is a wealth tax the answer? I don’t believe so when there are other alternatives.

Coincidentally, the same week – the same day – the Financial Times published an article which basically said higher taxes are coming.

The article argues the paradigm that we’ve operated under for the last 40 years since 1980 of relatively low taxes and smaller government has been broken.

Since March, governments have rightly embraced enormous deficits to limit the collapse in economic activity, protect incomes and sustain employer-employee relationships. As a result, public debt burdens are rising everywhere to levels not seen for many decades, or even ever before. According to the OECD, many of its member governments could add debt worth 20 to 30 percentage points of gross domestic product this year and next.

This is going to force a simple choice on just about every government. They can tolerate the high debt burdens indefinitely, rather than try to bring them back down to moderate levels. Alternatively, they can permanently increase the state’s tax take to balance the books and start whittling down the debt. Either way, combining “responsible” policies on both debt and tax burdens is no longer an option…We may have to jettison both and learn to live with permanently higher public debt and permanently higher taxes.

The article goes on to cite the example of Japan which in 2000 had a tax to GDP ratio of 25.8% which was then well below the OECD average. This has now risen to 31.4%, which is still below the OECD average of about 34%.

And the article notes, “if Japan is a harbinger of the future for all rich economies, then expect public debt to stay high and taxes to move higher”. So that’s going to be a reassuring thought to be considering when we listen to what the politicians talk about tax going forward.

An unemployment insurance scheme coming?

And finally this week, something interesting popped up, which was also slightly related to a Green Party policy in relation to ACC. Grant Robertson, the Minister of Finance, raised the idea of a permanent unemployment insurance scheme.

Now, this is something that the ACT party has also advocated. As the Productivity Commission noted most OECD countries have some form of employment and unemployment insurance, which people can draw down for a set period of time if they lose their job. This tends to help people in employment on middle and higher incomes,

We don’t have unemployment insurance at the moment. Instead we have Jobseeker Support, which at $250 a week is substantially well below what the people who’ve just lost their jobs were earning. And that is why the Government introduced a special package for people who have become unemployed as a result of Covid-19 since February. Basically paying them close to double what’s available under Jobseeker Support.

Another option might be to significantly increase benefits, which is what the Welfare Expect Advisory Group recommended. But that, of course, means putting more strain on the government’s finances which leads us back to the question of whether higher taxes are needed.

And on that bombshell that’s it for this week. Thank you for listening. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you find your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time, ka kite anō.

14 Apr, 2020 | Tax News

Are extra expenses and use of personal assets to work from home deductible against your taxable income? As usual with tax, its complicated.

We’re in week three of the Lockdown, and although the Prime Minister has indicated there may be a possible shift to Level 3 from 22nd April, a majority of employees may still be required to work from home even after that shift.

Naturally, employees will be incurring expenses in carrying out their employment duties. And the question arises, can they claim a deduction for these expenses? And the short answer is no. The Income Tax Act specifically precludes a deduction for “An amount of expenditure or loss to the extent to which it is incurred in deriving income from employment. This rule is called the employment limitation.”

This is a longstanding prohibition which has been in place since the mid-1990s. It was introduced as part of a simplification of tax return filing requirements. Instead, what is to happen is that the employer needs to reimburse employees for such expenditure. The employer will be given a deduction for the relevant expenditure and it will be treated as exempt income of the employee.

But what potentially could be deductible? The Inland Revenue guidelines for businesses with home offices are equally applicable for employees working remotely.

These guidelines allow a deduction of 50% for the rental of a telephone line, if it is also a private line which is used for business. Obviously specific business calls would be deductible. With regard to Internet costs this depends on the plan and the business proportion. How that is determined is a matter of some judgement. In addition to these costs, the business proportion of household expenses such as rates, power, rent or mortgage interest expense could be claimed.

Generally, the business proportion is calculated as the area set aside for use as an office over the total area of the house. For example, if an employee has an office which is say, 10 square metres of a 100 square metre house, then the deductible proportion is 10%.

There’s an alternative option of using a fixed rate as determined by Inland Revenue based on the average cost of utilities per square meter of housing for an average New Zealand household and applying it per square metre of the office area.

For the 2018-19 income year the rate was $41.70 per square metre so in the example above the deduction would be $41.70 x 10 or $417. It does not include the costs of mortgage interest rates or rent and rates. These must be calculated based on the percentage of floor area used for business purposes.

All of the above is perhaps easy enough where a person has a dedicated office at home, but as no doubt is happening all over New Zealand right now, employees are working on kitchen tops, dinner tables and out of bedrooms. What happens in these instances?

As the area being used cannot be said to be entirely dedicated to office use, a full deduction based on these apportionments is probably not available. The area of the room used for non-business purposes for example a bed or other furniture should be excluded. Arguably the deduction would be time-limited (for example, if it was only in office use for 8 hours a day, then only one-third could be claimed).

For the employer, they may be able to claim GST on the relevant proportion of GST expenditure claimed using the standard apportionment methodology, if the employee provides invoices. At this point the employer is probably thinking this is getting needlessly complicated.

A more practical approach would be for the employer to simply pay a flat rate allowance to employees. This is allowable if the allowance is based on a “reasonable estimate”.

The other potential issue is fringe benefit tax. Theoretically, FBT applies on the private use of tools such as mobile phones and laptops. Fortunately, there is an FBT exemption if the laptop or mobile phone is provided mainly for business use and the cost of those laptops and mobile phones is no more than $5,000 including GST.

All of the above represents a compliance nightmare for employee employers and possibly a target rich environment for Inland Revenue in a future date where it considers that the allowances paid, or deductions claimed for home office expenditure, have been excessive. In this instance the employer will be liable for the PAYE which should have been deducted from the amount determined to be excessive/non-deductible.

In practical terms, Inland Revenue might simplify clarify a lot of issues for employers and employees alike by issuing a determination setting out a flat rate amount of expenditure it would consider acceptable. An employer could pay above that amount but then PAYE would be applicable.

Of course, all of the above is somewhat hypothetical, if the employer has no cash flow to pay any such allowances. I suspect that is the matter employers are most concerned about right now. In the meantime, let’s hope we can return to a new normality soon.

This article was first published on www.interest.co.nz

14 Apr, 2020 | The Week in Tax

- More on Inland Revenue’s criteria for relief as a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic

- The fringe benefit tax lesson from David Clark’s misadventures

- The pros and cons of a Financial Transactions Tax

Transcript

This week, Inland Revenue has been updating its guidance as to the measures that have been introduced by the Government to help in the short term and longer term with the response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

In particular, Inland Revenue has given more guidance about what its position is around the remission of late filing penalties and use of money interest for tax that is paid late.

The position that has been set out and circulated in some detail to tax agents is as follows. In order to be eligible for remittance, customers – that deathly phrase – must meet the following criteria. They have tax that is due on or after 14 February 2020, and their ability to pay by the due date – either physically or financially – has been significantly affected by Covid-19.

They will be expected to contact the Commissioner “as soon as practicable” to request relief and will also be required to pay the outstanding tax as soon as practicable.

As to what “significantly affected” means, Inland Revenue’s view is this is where their income or revenue has been reduced as a consequence of Covid-19, and as a result of that reduction in income or revenue, the person is unable to pay their taxes in full and on time.

Now a couple of things to think about here.

“As soon as practicable” will be determined on the facts of each case according to Inland Revenue. So that as long as the taxpayer applies at the earliest opportunity and then agrees to an arrangement that will see the outstanding tax paid at the earliest opportunity or be paid over the most reasonable period given their specific circumstances, then that test will be met.

However, what you also need to know is that this is very much on a case by case basis, so that if Inland Revenue thinks you’re trying to pull a fast one, they will deny remission and you will be up for the late filing penalties and use of money interest.

Now, in terms of applying for remission of use of money interest, Inland Revenue is saying it would try and minimise the amount of information it normally asks to be provided, accepting that these are unusual times. But they want people to continue to file their GST returns. So in other words, you may not be able to pay your GST on the regular time, but you should still file it, so that gives them information as to what’s going on.

Obviously, if things have really dived into a hole for a taxpayer, filing a GST return may be a means of getting a refund. Although if you owe tax to the Inland Revenue, that would simply be swallowed up and applied to any arrears.

But in terms of information, Inland Revenue are saying they would expect to see at least three months of bank statements and a credit card statement, any management accounting information and a list of aged creditors and debtors. Inland Revenue goes on, we may not ask for that all that information in every case, but it should be available if we do ask for it.

For businesses, they will be looking to see and to understand what your plan is to sustain your business. You may not be able to get all that information to them; they’ll work around that. So, they’re clearly trying to be as flexible as possible.

Obviously some people were already in trouble before 14 February, so they can ask to renegotiate their existing instalment arrangement with Inland Revenue. Very simply,what will happen is that you enter into an arrangement with Inland Revenue that you’re going to pay X amount at a regular time to meet your liabilities. Inland Revenue have said in some cases they will accept a deferred payment start date.

They may partially write off some of the debt because of serious hardship but expect the remainder to be met by instalment or a lump sum. They may also even write it off completely due to serious hardship. It’s all going to be done on a case by case basis. So that’s the most important takeaway.

Inland Revenue’s communications around remission of late payment penalties and use of money interest are a little confusing, in that it seems to say that anyone paying late will be able to get remission of use of money interest on late payment penalties. That is not the case. It must be Covid-19 related and you must demonstrate that.

As it is being done on a case by case basis, be aware that if you don’t meet the standards that Inland Revenue are expecting to see, they won’t grant you the remission. So that’s the key take away at the moment.

Now, in previous podcasts I have raised the possibility of the 7th May provisional tax and GST payments being postponed. The problem is that Inland Revenue doesn’t have the authority to do that, even though it sounds like a great idea. With Parliament essentially in recess, it’s not something that can be done quickly either. So that’s probably something that longer-term legislation may need to be introduced to give Inland Revenue the flexibility to deal with unexpected events.

It probably felt it had enough flexibility to manage the situation in the wake of the Canterbury earthquakes, but as this Covid-19 pandemic has shown, when it happens nationally, not just regionally, then extra powers or extra flexibility may need to be granted statutorily.

A quick note on Inland Revenue. Remember that it is closing all online and telephone services and their offices as of 3p.m. today. This is to finalise Release Four of their Business Transformation Program. As I said in last week’s podcast, I agree they should continue to do this. They’ve probably put a lot of work in place beforehand, and it’s going to be more disruptive for them to postpone it. So at a time when productivity does fall away a little bit – it’s after the 31 March year end and it’s around Easter – this is as good a time as they’ll ever get to do it. Services will be back up and running from 8a.m. next Thursday.

Just a final quick note on that – remember, if you’ve got a return or e-file in draft or any draft messages in your MyIR account, those will be deleted. So you should complete and submit them before 3p.m. today.

FBT surveillance

Moving on, there’s a useful little tax lesson from David Clark’s – the Minister of Health – misadventures, and it’s in relation to the photograph that’s been widely circulated of his van sitting isolated in a mountain bike park.

We’re going to see more of Inland Revenue going through social media and picking up signage on vehicles and then matching that signage to its records about fringe benefit tax.

What happened there, someone obviously saw David Clark’s van which had his name and face written all over it and passed it on to a journalist and the story ran from there.

That already happens to some extent with Inland Revenue already looking at people’s use of work-related vehicles. In particular, the twin cab use, which I’ve mentioned before, is something that I know Inland Revenue is now starting to look more closely at in terms of FBT compliance.

You get chatting to Inland Revenue officials and investigators and they’ll have some great stories about how taxpayers have accidentally dobbed themselves in by driving their work-related vehicle towing their boat to, say, a wharf opposite the Inland Revenue office in Gisborne was one story I heard.

So David Clark’s misadventures should be a highlight that if you’ve got a sign written vehicle and you are claiming a work related vehicle exemption, don’t be surprised if Inland Revenue starts matching up your Facebook profile, for example, with your FBT returns and asks questions. This is part of the brave new tax world we live in and is something we will see a lot more of.

Financial transactions tax

Finally for this week, I mentioned in last week’s podcast I did a Top Five on what I saw as the possible future tax trends post Covid-19. One of the things I talked about was greater use of artificial intelligence and data mining and information sharing by Inland Revenue – just referencing back to my previous comment by David Clark and FBT.

I also discussed the likelihood of new taxes coming in. And one of the taxes I commented on was a financial transactions tax and that perhaps that it’s time might come.

But the drawback, as I saw it for a financial transactions tax, is that it needs to be applied globally. And one of the readers asked the following question

“Why does a FTT need to be universal? In the context of your article, I read global as meaning why can’t the New Zealand government apply for all transactions in New Zealand, especially for money leaving the country?”

It’s a good question and so I dug around a bit more on the topic. A financial transactions tax sometimes also called a Tobin tax after the economist who first mooted it, is a tax on the purchase, sale or transfer of financial instruments.

So as the Tax Working Group’s interim report said, a financial transactions tax or FTT could be considered a tax on consumption of financial services.

And FTTs have been thought of as an answer to what is seen as excessive activity in the financial services industry such as swaps and the myriad of very complex financial instruments. Some people consider many of these as just driving purely speculative behaviour and a FTT could be something that would actually help smooth some of the wild fluctuations we sometimes see in the financial markets.

Now, the Tax Working Group’s interim report thought the revenue potential of a financial transactions tax in New Zealand was likely to be limited “due to the ease with which the tax could be avoided by relocating activity to Australian financial markets.”

And this is what I meant by saying a FTT had to apply globally. If you’re going to have a financial transactions tax, you need to have it as widely spread as possible across as many jurisdictions. Otherwise, you’ll get displacement activity.

Now, it so happens I’m looking at Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty First Century, and he had an interesting point to make about a FTT. And that is that it is actually a behavioural tax, because, as he has put it, its purpose is to dry up its source. In other words, think of it like a tobacco tax. The intention there is not just to raise revenue, its primary function is to discourage smoking.

So a financial transactions tax has the same effect. It drives down behaviour that you don’t want while raising money. But the fact it is driving down transactions means that its role as a significant producer of income for the Government is limited.

Piketty suggests its likely revenue could be little more than 0.5 percent of GDP. The European Union when it was considering a FTT of 0.1% thought it might raise the equivalent of somewhere between 0.4% and 0.5% percent of GDP. (about EUR 30-35 billion annually in 2013 Euros). 0.5% of GDP in a New Zealand context would be maybe $1.5 billion. Not to be ignored, but still not a hugely significant tax.

The other issue that the Tax Working Group were concerned about – and I think this is something that we really want to think about in the wider non-tax context – is that any relocation to Australia, for example, would reduce the size of New Zealand capital markets.

And I think this is a long-term structural issue in the New Zealand economy we ought to be considering more seriously – in the wake of what comes out of the initial response when Covid-19 pandemic ends, how the economy looks going forward. This will be one of the issues to look at.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website, www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients until next time. Happy Easter and stay safe and be kind. Kia Kaha.

17 Feb, 2020 | The Week in Tax

- Shareholder advances under Inland Revenue scrutiny – are you paying FBT on these advances?

- More about using cheques to pay tax

- Australian tax complications when purchasing property

Transcript

This week, Inland Revenue gets curious about loans to shareholders. More about how you can pay your tax and the cost of investing in Australian property just went up.

Listeners will recall one of my previous guests was Andrea Black, who at the time was the independent advisor to the Tax Working Group. Andrea has moved on and is now the policy director and economist at the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions taking over from Bill Rosenberg, a fellow Tax Working Group member.

Andrea has just published a Top Five piece on tax and paid employment.

And one of the top five items caught my eye, because it picks up some other things that I’ve been seeing, has to do with advances from companies to shareholders.

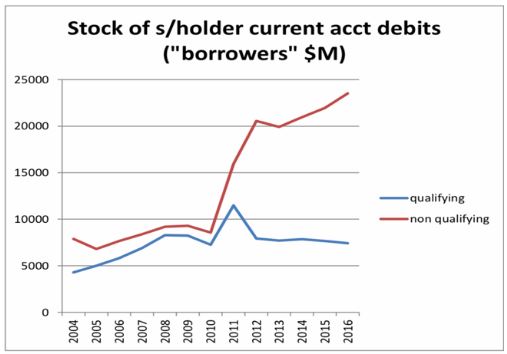

Now, the interesting thing that’s emerged from the Tax Working Group is what happened after 2010 when the tax company rate was cut from 30% to 28% and at the same time the top personal tax rate went down from 38% to 33%. Since then amount of loans advances from companies to shareholders has exploded, and there is an eye-catching graph in a Tax Working Group paper which shows the value of shareholder current account advances.

And they’ve gone from just under $10 billion in back in 2010 to nearly $26 billion by 2016. So, what’s happening here? Well, it appears that this could be a way of people trying to avoid paying the top 33% tax rate because company profits are tax paid at 28% and then the taxpayer then receives an imputed dividend and then tops up the 5% differential, assuming they’re taxed at the top rate.

But what happens if instead the money is advanced as an interest free loan or a loan to a shareholder? Now, there are rules around this, and interest free loans are subject to a prescribed interest rate. This has been cut to 5.26% with effect from 1st of October 2019. If you’re not charging interest, you are required to charge this prescribed interest rate of 5.26% on any overdrawn shareholder current account.

Now that is a longstanding rule, but in my experience, it’s not always observed, and I even had an interesting case at the start of an Inland Revenue review. The company did have an overdrawn current account for some shareholders. We advised Inland Revenue as you are supposed to saying “Look, oops our bad. This is an overdrawn current account and we haven’t been charging interest. Here’s the amount of interest we should have been charged”.

What was interesting about this case was it involved a fairly sizable company which had independent advisors, who ought to have known this. More curiously, the Inland Revenue investigator didn’t seem to be aware that that this could have been a problem. Perhaps this is why these current account debits have been gradually growing without too much observation from Inland Revenue.

So, the issue which arises here is have those companies being charging interest and if so, have they charged interest at the correct rate? Otherwise, there’s probably a load of FBT going to be payable. And why exactly are they doing this? If there is a constant pattern of substitution of, say, a salary or dividends with drawings made through the current account, Inland Revenue could follow the lead it took in the Penny-Hooper case. You may remember that case from nearly ten years ago. Inland Revenue may say, “Well, this actually constitutes tax avoidance and we’re going to treat these drawings as additional salary or remuneration”.

So, it remains to be seen what’s going to happen in this case. This is another head’s up. If you’re a company and you’re advancing money to your shareholders and you’re not charging the prescribed interest rate of 5.26% then you potentially have a problem on your hands.

And what I think we can also say with some confidence is that matters highlighted by the Tax Working Group as requiring work will be picked up by Inland Revenue as part of their work programme. The data mining capabilities of the Inland Revenue are now greatly enhanced, so I would anticipate seeing a lot more “Please explain” letters coming from Inland Revenue investigators.

Following on from last week’s item about the fact that Inland Revenue is withdrawing the general application ability to pay tax by cheques from 1st of March, earlier this week I went to a meeting between tax agents and Inland Revenue staff. And this point got raised with several agents saying, “Well, we’ve got elderly clients who either have no access to online banking or don’t know how to use it. They’re not happy about it. And we’re not happy about this”. Two things emerged from this discussion. Firstly, the Inland Revenue staff acknowledged this was something that was a potential problem. But they also pointed out that in fact, in certain circumstances, Inland Revenue will allow cheques to continue to be used to meet tax payments. Coincidentally, also this week, a new Statement of Practice SPS 20/01 was released by Inland Revenue which explains when it considers tax payments to be made on time.

The SPS discusses what the alternatives for people who used to pay by cheque, and can and are concerned they may no longer do so. And it gives a couple of examples about the options. One involves John who lives in a remote rural area and lives off the grid. He does not have any access to the internet nor a reliable phone service and is hours away from any banks. So, in this case, Inland Revenue would agree that his circumstances are exceptional, and he may continue to pay his tax by cheque after 1st March 2020.

The alternative example is another elderly person, Mary who is aged 75. She doesn’t have access to the Internet either. She has no Westpac branch. (You can actually rock up to a Westpac branch and pay your tax in cash or by using a debit card). Mary does have an EFTPOS card and the Inland Revenue here say:

“Through discussion with the customer about her circumstances, it was agreed that she is able to, with assistance by phone, set up a direct debit with us, or make payments using an automatic payments form. On this basis, an exceptions arrangement to pay tax by cheque post 1 March 2020 would be declined.”

So, there are instances that you can still continue to pay by cheque, but it’s very much a case by case basis.

I stand by what I said last week. I think that this is blanket policy which should not be allowed. I would say in that example they give about Mary, elderly people like that would be very, very cautious about talking over the phone to someone about paying tax. Particularly since Inland Revenue is sending out frequent reminder warnings about the phishing and phone scams going on.

So, I think you’ve got this dichotomy between Inland Revenue wanting to minimise its own administrative costs and not actually addressing the real concerns of people who are concerned about using online and phone banking.

The second point came out of the discussion was also pretty interesting, was that Inland Revenue had also said that in future, when either setting up or updating your bank account details, it would require a direct debit.

Now, that caused quite a stir amongst the tax agents. And let’s just say there was a full and frank exchange of views on the matter, which also coincided with us being advised that, in fact, that particular advice was going to be withdrawn. Clearly, quite a lot of people have said, “Wait a minute, what’s this?” because cancelling the direct debit with Inland Revenue is not that easy. The takeaway here is you do not have to set up a direct debit with Inland Revenue unless you really want to. Therefore, proceed with caution.

And finally, and this is a long running issue for me, a warning how the tax consequences of investing in Australia are often overlooked. There is a lack of awareness that, first of all, Australian capital gains tax will apply to property. But secondly, there’s also all the other hidden charges involved in investing in Australian property, such as Stamp Duty – or as they call it in New South Wales – Transfer Duty.

What caught my eye this week is that the state of Victoria, has announced it will withdraw its grace period for exempting foreign purchaser additional stamp duty on residential property.

This would apply to discretionary trusts that have foreign beneficiaries, for example, a New Zealand trust with, say, three beneficiaries here and one in Australia. This will now become regarded as a foreign trust for surcharge tax purposes unless the trust deed is amended to expressly exclude the foreign persons, that is the New Zealand residents as potential beneficiaries of the trust.

The change may mean that there will be a surcharge payable on the purchase by a New Zealand trust of residential property in Victoria. New South Wales has similar rules. In fact, there is a Surcharge Purchasers Duty of 8% for residential land purchases by foreign persons, which would include a foreign trust. New South Wales also has a land tax and it imposes a 2% surcharge for residential land purchases by foreign persons.

So, this is very much a case of if you’re investing in Australia, be aware there are great tax complications. I always tell my clients, “Don’t let the tax tail wag the investment dog”, but you really have to be sure if you are investing in Australian property that the returns justify the additional tax consequences that you’re going to incur.

And on that bombshell, that’s it for The Week in Tax. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next time have a great week. Ka kite āno.