25 Jul, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Depreciating buildings

- Who are taxed the heaviest?

- The OECD says housing should be taxed

Transcript

Inland Revenue has released Interpretation Statement IS 22/04 on claiming depreciation on buildings. Critical to this issue is determining the meaning of a “building” for depreciation purposes and the distinction between residential and non-residential buildings. The Interpretation Statement addresses this issue when it sets out when depreciation may be claimed for non-residential building and also for some fit outs. It confirms that no depreciation is available for residential buildings.

The Interpretation Statement then sets out where you can find the right depreciation rate for buildings when fit outs attached to buildings may be depreciable. How to treat an improvement of a building for depreciation purposes. And then finally, what happens when the building is disposed of or its use changes?

To recap, depreciation for all buildings was reduced to zero, with effect from the 2011-12 income year. Back in 2020 as part of the initial response to the pandemic, the Government reintroduced depreciation for non-residential buildings with effect from the start of the 2020-21 income year. Generally, the depreciation rate is 2% on a diminishing value basis, or 1.5% on a straight-line basis. Some other depreciation rates may be used where the building has a shorter than normal useful economic life. Examples would be barns, portable buildings or hot houses. Additionally, it’s possible to claim a special rate if the building is used in an unusual way.

Now for depreciation purposes “building’ retains its ordinary meaning which means anything that is structural to the building or used for weatherproofing the building. The Interpretation Statement emphasises that whether a building is residential or non-residential is an all or nothing test. If the building is non-residential depreciation is available, otherwise not, there’s no apportionment.

Residential buildings are any places mainly used as a place of residence. This includes garages or sheds included with that building. Places used as residential residences for independent living in retirement villages and rest homes are residential buildings are is short stay accommodation where there’s less than four separate units.

On the other hand, non-residential buildings include buildings used predominantly for commercial and industrial purposes, but not residential buildings. This also includes hotels, motels, inns, boarding houses, serviced apartments and camping grounds. Retirement villages and rest homes where places are not being used for independent living are non-residential buildings as is short stay accommodation where there are four or more separate units.

If improvements are made to a building, you must treat it as a separate item of depreciable property in the first tax year. Then you can either continue to treat it as a separate item of depreciable property or simply add it to the building by increasing the adjusted taxable value of the building.

In some cases, a fit out can be separately depreciated depending on the nature of the building and the nature of the fit out. Where the fit out is considered structural to the building or used to weatherproof the building it must be treated as part of building and not depreciated separately. Fit outs are depreciable in a wholly non-residential building and sometimes in a mixed-use building. But remember, the key point is that depreciation is not available under any circumstances for a residential building. So overall, this is a useful Interpretation Statement and is also, as has become the norm, accompanied by a very handy fact sheet.

The agencies tackling organised crime and its tax evasion

Moving on, last week I discussed a suggestion by ACT Party leader David Seymour to use Inland Revenue against the gangs. I looked at the powers available to Inland Revenue and discussed how practical his proposal was. To summarise, Inland Revenue has extensive powers which would be useful in tackling gangs and organised crime. However, this is a resource intensive approach which probably in Inland Revenue’s view, would divert its attention from other areas it considers equally important.

This prompted some discussion in the comments section and thank you again to all those who contributed. As I said, my view is Inland Revenue probably thinks other agencies, such as the Police, are better suited for this activity. But it will cooperate with those agencies. Its annual reports make clear they pass information to other agencies. So Inland Revenue is probably working on this matter in the background.

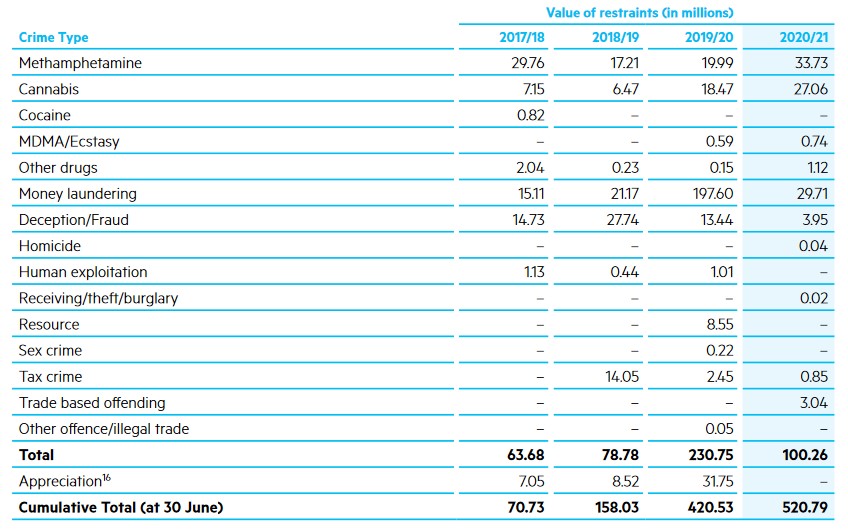

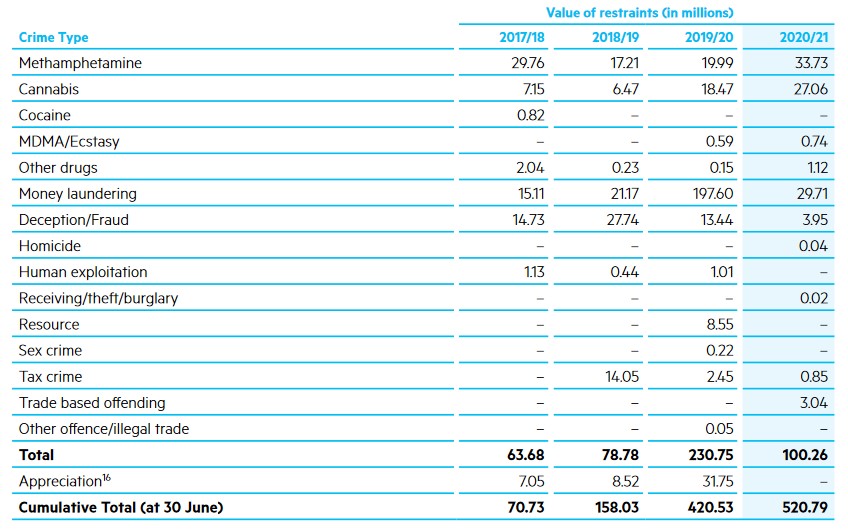

It was interesting just to take a look to see what other agencies were doing in this space and get a gauge of what’s happening. A key tool for the Police is the use of restraining orders to seize assets. According to the Police’s Annual Report for the year ended 30th June 2021 the value of restraints for the year totalled just over $100 million, including nearly $30 million seized from anti-money laundering.

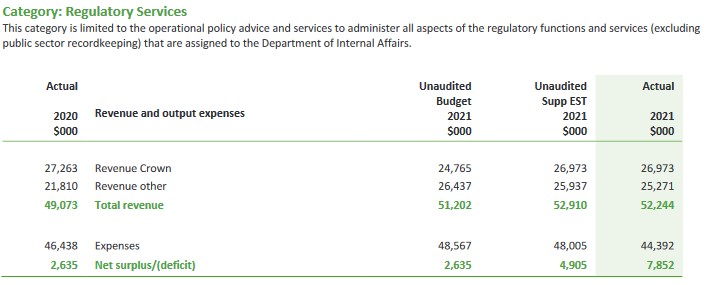

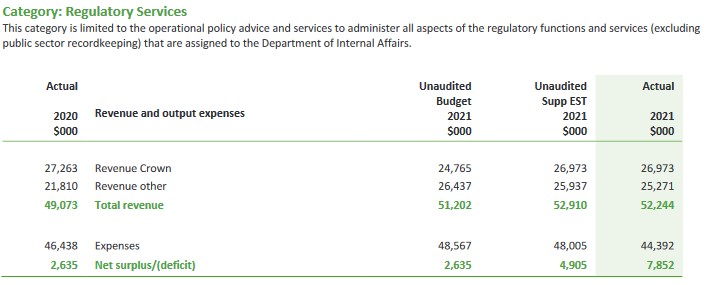

The Department of Internal Affairs also has responsibilities for anti-money laundering, as it’s a key regulator on that. Its Annual Report to June 2021 indicates that perhaps it could do more in this space, as its budget for its regulatory services for the year was set at $52 million, but it only spent $44 million.

And then when you look at the DIA’s performance metrics, such as desk-based reviews of reporting entities, it’s supposed to be targeting between 150 and 350 such reviews annually, but managed only 219 for the year, up from 198 in the previous year. And on-site visits were meant to be somewhere between 70 and 180 but came in at 79. To be fair these were probably disrupted by the impact of COVID 19.

Still, there are other agencies involved in pursuing gangs including Customs who will also be very interested. Inland Revenue will be playing a role, it shares information with these other agencies. So even if it’s not wielding a very big stick publicly, it’s working in the background.

The interaction of tax and abatements on social assistance

Now tax has been in the news a lot recently with the election coming up even though it’s still just over a year away probably. National and the ACT Party have both set out they would proposed some tax cuts. Last Saturday, Max Rashbrooke, a senior associate at the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies, who has written quite a lot on wealth and taxation put out some counter proposals to National and ACT’s proposals.

He suggested that really the focus should be on middle income earners. And he made a suggestion, for example, that we could have a $5,000 income tax free threshold, something we see in other jurisdictions. Britain’s is just over £12,500, Australia’s is A$18,200 and the US has a slightly different thing. It gives you a standard deduction of US$12,000. But anyway, let’s take that comment elsewhere. And Max suggested that something could be done in that space.

But it got me thinking about the question of who does actually pay the highest tax rates in the country. And the answer isn’t those on over $180,000 where the tax rate is 39%, it’s actually more around $50,000 mark if those people are receiving any form of government assistance, such as Working for Families. If they have a student loan as well, then an additional 12% of their salary after tax gets deducted.

The interaction of tax and abatements on social assistance, such as the family tax credit and parental tax credit can mean in some cases, the effective marginal tax rate for some families is more than 100% on every extra dollar they’re earning. This is an issue which the Welfare Expert Advisory Group touched on, but the Tax Working Group wasn’t allowed to address. But it’s a huge problem.

Take, for example, someone earning $50,000, just above the $48,000 threshold where the tax rate goes from 17% to 30%. And that, by the way, is the rate where I think we need to focus our attention on adjustments to thresholds and tax rates. At that level every extra dollar they’re earning is taxed at 30%. If they’ve got a student loan then they pay a further 12%. If they have a young family and are receiving Working for Families tax credits, then these are abated at 27%. Incidentally, the abatement threshold is $42,700. So that means that that person is on a marginal tax rate of 69%. Definitely not nice.

Then there’s a separate credit, the Best Start tax credit which has a separate abatement regime in addition to the Working for Families abatement regime I just explained. So that’s why people could be suffering an effective marginal tax rate of over 100%.

In my view, this is the area where we really need to be thinking about changing the tax system, because to compound matters, governments have been very cynical about not adjusting thresholds for inflation, something I’ve raised repeatedly in the past.

Working for Families thresholds were adjusted for inflation every year until National was elected in 2008. Starting in the 2010 Budget they started freezing thresholds. They also increased the abatement rate which used to be 20% and is now 27%. The current Working for Families abatement threshold is $42,700, which is less than what someone working full time on the minimum wage will earn annually

Looking at student loans the threshold where repayments start in 2009 was $19,084. That is now $21,268 but for a long period of time under the last government it was frozen. National also increased the repayment rate from 10% to 12% in 2013.

So this is an area where governments of both hues have been really quite cynical in my view, and where a lot of serious thought needs to go in about trying to address the inequities that have arisen. The Welfare Expert Advisory Group suggested the abatement rate should be 10% on incomes between $48,000 and $65,000, then increase to 15% before rising to 50% on family incomes over $160,000. (Yes, large families with that level of income could be receiving social assistance in some instances).

There’s a lot of work to be done in this space and inflation adjustments to thresholds is something that should be done anyway. But I think we need to think carefully around the thresholds and how the interaction with social assistance works. At the moment we’re not getting that sort of analysis from either any of the main parties and that’s disappointing, as it’s something that really needs to be addressed.

Why the FER deals with recurrent taxes better

And finally this week, just hot off the press is an OECD report on Housing Taxation in OECD countries. This makes for some interesting reading. Briefly, the report is concerned about how housing wealth is mostly concentrated amongst high income, high-wealth and older households. And in some cases, they believe that a disproportionately large share of owner-occupied housing wealth is held by this group. There’s been unprecedented growth in house prices, not just in New Zealand, but across the whole OECD, making housing market access increasingly difficult for younger generations.

In terms of suggestions the OECD believes that housing taxes are “of growing importance given the pressure on governments to raise revenues, improve the functioning of housing markets and combat inequality.” The report notes the way housing taxes are designed often reduces their efficiency. Recurrent property taxes, such as rates, are often levied on outdated property values, which significantly reduces their revenue potential. This also reduces how equitable they are because where housing prices have rocketed up, people are underpaying based on current values. And conversely people in places where prices are falling or have been stagnant are paying more relative to those in richer areas.

One of the suggestions the report makes is that the role of recurrent taxes on immovable property should be strengthened, by ensuring that they are levied on regularly updated property values. And this is one of these reasons why Professor Susan St John and I have been promoting the Fair Economic Return approach. One of the strongpoints of our proposal would be strengthening the role of recurrent taxes.

Capping a capital gains tax exemption on the sale of a primary residence

Another proposal would not at all popular. It is to consider capping the capital gains tax exemption on the sale of main houses so that the highest value gains are taxed. This should strengthen progressivity in the system and reduce some of the upward pressures. This is what happens the U.S. There is a US$250,000 exemption on the main home per person, and above that the gains are taxed. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t have a similar type exemption here if we want to introduce a capital gains tax. But as I said, that would be particularly unpopular.

The OECD also believes there should be better targeted incentives for energy efficient housing, because housing, according to this report has a significant carbon footprint, maybe 22% of global final energy consumption and 17% of energy related CO2 emissions.

So, there’s a lot to consider in this report, and we come back to it and consider it in more detail. But again, it sort of comes to this point we’ve talked about repeatedly on the podcast, the question of broadening the tax base and the taxation of capital. These issues aren’t going to go away, particularly when you consider, as I mentioned a few minutes ago, how very high effective marginal tax rates are paid by people on modest incomes who may not have any housing. No doubt we’ll be discussing all these issues sometime again in the future.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

9 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Inland Revenue gets ready for tax filing season and puts recipients of COVID-19 support payments under the microscope

- Insights into the composition of the Top 0.1%

Transcript

Inland Revenue is currently gearing up to begin processing 31st March 2022 year-end tax returns and personal tax summaries. Starting later this month it will be issuing automatic income tax assessments for most New Zealanders. But in preparation for that it has been giving updates to tax intermediaries on particular matters of interest. And a couple of notifications in the latest release caught my eye.

Firstly, there is form IR833 bright-line residential property sale information return which is required to be completed whenever a transaction which is subject to the bright-line test has taken place during the tax year. What Inland Revenue is saying is the form will pop up in a client’s return if it thinks the client has made a bright-line sale. And it will also pre-populate the information on the form, including the title number, address, date of purchase and date of sale.

This illustrates something we’ve spoken about many times, the level of information that’s available to Inland Revenue. It’s actually very good, in my view, that Inland Revenue is proactively putting in this information and saying, “Well, we know this.” I am aware that a few tax agent colleagues have had some very interesting discussions with clients where this notification has popped up and it’s the first the accountant or tax agent has heard about the matter.

As of last income year, all portfolio investment entity (PIE) income must be included in individual income tax return. Inland Revenue will pre-populate returns with the relevant data but not all returns will contain all the PIE information until after the PIE reconciliation returns and filed on or before 16th May.

In the meantime, Inland Revenue has reminded tax agents about this and advised not to file March 2022 tax returns either through Inland Revenue’s myIR or other tax return software until after that date unless you know for certain that the client is not a KiwiSaver member and does not have any other PIE income. That’s something to keep in mind because I’m sure some tax agents will be under pressure from clients who think that they are due a refund but haven’t factored PIE income into the equation.

What’s also going into tax returns is details of payments received under the Wage Subsidy Scheme, Leave Support Scheme and Short-Term Absence Payments. All these are what are termed reportable income. Consequently, tax returns will be required to be filed by recipients and there is going to be an information request in relation to these as part of the tax returns. Yet again, this is another example of how MSD and Inland Revenue shared the relevant information.

Inland Revenue administers the highly successful Small Business Cashflow Scheme which gave out loans to small businesses at the start of the pandemic. The initial two-year interest free period is now expiring for some businesses so repayments will be required to start shortly.

Talking about COVID-19 support, the numbers involved were quite extraordinary: apparently MSD has so far paid out $19.28 billion in the various subsidies and leave support payments. And Inland Revenue has paid out another $3.95 billion including Resurgence Support Payments and COVID-19 Support Payments.

The Resurgence Support and COVID Support payments were paid to businesses to help them pay business costs and therefore GST output tax is required to be returned on those receipts. Where the funds are used on relevant expenditure GST input tax credits may be claimed.

Inland Revenue has started checking that those who claimed the support payments were entitled to do so and assuming they passed that hurdle, they then applied the expenditure as was intended, i.e. business expenses. And I’m hearing stories from tax agents of very thorough investigations combing through the bank accounts of the businesses and individuals who received these payments. Some have resulted in “Please explain” enquiries coming back where apparently personal expenditure has been identified such as in one case where an EFTPOS payment for McDonald’s was identified.

This is yet another warning for those who applied for COVID support payments they either weren’t entitled to or misapplied the payments that they may find themselves under the gun from Inland Revenue. So far Inland Revenue have decided to proceed with 15 criminal charges and court proceedings are already underway for seven. In addition, as a result of investigations and some self-reviews the repayments made to date to MSD are over $794 million. ,

All of this is a timely reminder that with things calming down a little bit and so coming back to a stability, Inland Revenue is now applying itself back to its core business activities of investigations and reviews. Expect to see more news of these reviews and I think we may see one or two interesting cases emerge.

What Parker means

Moving on, last week’s speech by the Minster of Revenue David Parker quite predictably caused a stir and there was plenty of politicking over whether or not the proposal would lead to the introduction of wealth tax at some point and whether the Prime Minister would stand by her comments it wasn’t going to happen, the usual politicking etc. etc.

Subsequently, last Sunday I appeared together with Jenée Tibshraeny of www.interest.co.nz on TVNZ Q&A to discuss the implications of Mr. Parker’s speech. Off-air Jenée made a point echoed by several colleagues commenting on a LinkedIn post that the Tax Principles Act, if enacted, would work both ways. It wasn’t just a tool for saying, “Well, we need to introduce a particular type of tax.” It could equally stop a government introducing changes because it contradicted the agreed principles.

It’s a very valid point and it’s actually one of the sources of disagreement with the introduction of the 39% tax rate, because it affects the integrity of the tax system and the idea of administrative efficiency. Furthermore, it could apply to the measures relating to personal services, income attribution, which also I discussed last week. The argument here is that these rules would breach potential principles of horizontal equity, in that people earning similar amounts, may pay different rates of tax because of variations in the tax treatment.

Under the microscope

Other interesting insights have emerged in the wake of the speech. The Revenue Minister pointed to the lack of information about the high wealth individuals which prompted the research project into high wealth individuals would have caused some controversy. And earlier this week journalist Thomas Coughlan in the New Zealand Herald commented on an interesting briefing note about the project he’d obtained under the Official Information Act.

The briefing note looked into the representativeness of the wealth project population, and whether the high wealth research project population effectively represented the 0.1% of the wealth distribution of the population and the economic sectors they operated.

The note explains that the group that was selected for the project was based on

…environmental scanning undertaken by Inland Revenue over the past 20 plus years. This environmental scanning involved monitoring large transactions or other indications that individuals had significant wealth holdings using both public information and the department’s tax data. …

The briefing notes the selection is non-random and it is not expected to be representative of the population of all high wealth individuals. It is therefore quite possible that there may be high wealth individuals missing from the group “and there is no way to definitively state that the selected group is representative of the top 0.1% of the wealth distribution.”

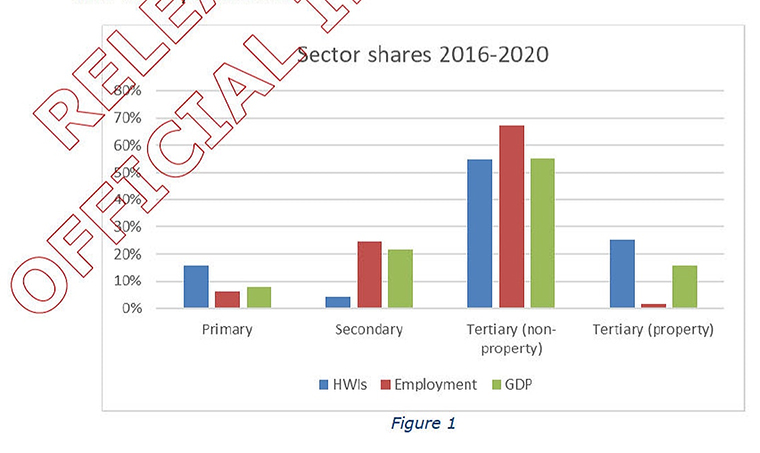

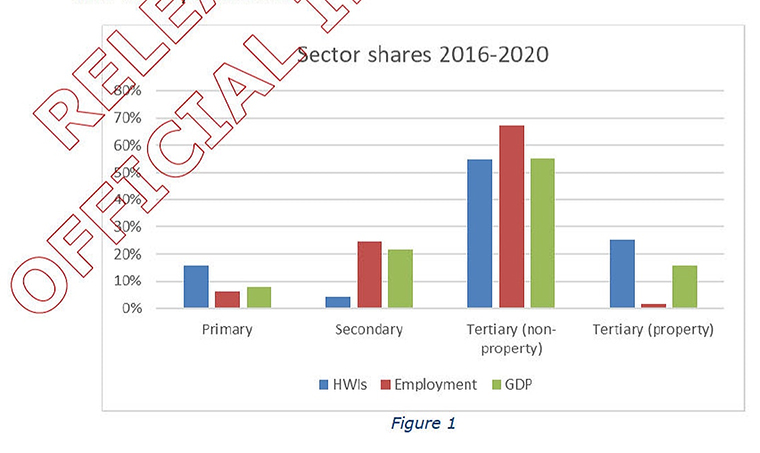

Having included that caveat, the note had some interesting analysis of what they had found so far. And it had a diagram comparing the share of GDP and employment to the main activities of high wealth individuals on the basis that you could reasonably expect the share of the industries represented by the individuals to be broadly similar to the spread of industries and activities in the New Zealand economy.

But it turns out that wasn’t the case. And in particular, relative to employment and GDP shares, the property and primary sectors are disproportionately represented in this project. The number of high wealth individuals in the primary sector is approximately 15%, even though the sector represents less than 10% of GDP. In relation to the property sector the proportion of high wealth individuals is 25%, compared with approximately 15% of GDP.

However, as the briefing note commented, there are clear reasons why there is this discrepancy “…there are certain activities (investment, property ownership) that would be expected to have greater involvement by those accumulate significant wealth….”

Incidentally, the primary sector and particularly the property sector, are sectors where existing tax rules such as the Bright-line test and the associated person rules work already to tax capital transactions. So that’s another reason why Inland Revenue may have better data on this particular group of wealthy individuals than others that work in the service economy.

Anyway, it will be interesting to see what further insights emerge from this high wealth research project. Meantime, no doubt the debate over how that data may be applied and the question of the taxation of capital and wealth will continue to rage, particularly in the run up to next year’s election.

Getting ready for tax filing season

And lastly this week, the final instalment of Provisional tax for those with a 31st March year-end is due on Monday. The key point here is taxpayers whose residual income tax liability for the year is expected to exceed $60,000, should ensure that they pay sufficient provisional tax to cover that total liability for the year. Otherwise, use of money interest, which is increasing to 7.28%, will start accruing together with potential late payment penalties.

As always, if taxpayers are struggling to meet payments in full, then either contact Inland Revenue to let them know and start to arrange an instalment plan. You will find that they are generally cooperative on this. Alternatively, consider making use of tax pooling to mitigate the potential use of money, interest and late payment penalties.

Well, that’s all for this week I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

2 May, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Minister of Revenue philosophises on tax and proposes a Tax Principles Act

- The IRS drops the ball

Transcript

Ministers of Revenue typically deliver several speeches during the year, mostly to business audiences or at the start of tax conferences.

On Tuesday, however, the Minister of Revenue, David Parker, delivered a speech at Victoria University Wellington entitled Shining a Light on Fairness in the Tax System, which is without doubt one of the most interesting speeches made by any Minister of Revenue in many years.

After some scene setting about the purpose of tax and how the Government has been able to use tax revenues to fund its COVID 19 response, Parker then pivoted to talk about beginning what he called a fact-based discussion. He started by challenging the assumption that our tax system is progressive overall.

“What’s hidden that the effective marginal tax rate for middle income Kiwis is generally higher than it is for their wealthiest citizens. Indeed, some of their wealthier Kiwi compatriots pay very low rates of tax on most of their income.”

The Minister then dived into the question of the lack of data on the distribution of wealth and capital income in New Zealand. He highlighted the fact that according to the Household Economic Survey, the highest net worth ever reported was $20 million.

This was, he said, ridiculous, given that we know there are billionaires in the country. As he pointed out, that meant the National Business Review’s annual rich list is a better set of data than the official statistics. In fact, that’s quite common around the world as statistics on capital wealth are rare and rich lists are often used to help revenue authorities gather data in this area.

So this lack of data, Parker explained, was the rationale behind the powers granted to Inland Revenue for the purposes of conducting research into high wealth individuals. As listeners will know, this is a somewhat controversial project, even though the Minister repeatedly stated that the intent was to gather better data for research and not as had been accused, so Inland Revenue could secretly work on new taxes.

“Until we have a much more accurate picture about how much tax the very wealthy pay relative to their full “economic income”, we can’t really we can’t honestly say that our tax system is fair.” And this led on to the most surprising part of the speech his proposal for a Tax Principles Act.

He referenced four principles of taxation that Adam Smith set out in Wealth of Nations back in 1776. And he noted that the many tax working groups and other reports that New Zealand has had over the past 40 years, such as the McCaw Review in 1982, the MacLeod Review in 2001, the most recent tax working group, and the all the work that went on during the Rogernomics period all basically followed these four principles set out by Adam Smith.

“They all endorse the same principles, based in that most core value of New Zealand – fairness. The main settled principles are:

Horizontal equity, so that those in equivalent economic positions should pay the same amount of tax

Vertical equity, including some degree of overall progressivity in the rate of tax paid

Administrative efficiency, for both taxpayers and Inland Revenue

The minimisation of tax induced distortions to investment and the economy.”

He also noted that recent reviews in the UK and in Australia both adopted similar approaches. Incidentally and perhaps not coincidentally here, Deborah Russell and I adopted the same principles when we wrote Tax and Fairness back in 2017.

And as you know, Deborah is now the Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Revenue and David Parker’s number two. The proposal is that officials should periodically report to ministers on the operation of the tax system using the principles as the basis for the reporting.

The Tax Principles Act would sit alongside existing legislation, such as the Public Finance and Child Poverty Reductions Acts, which also require the Government and officials to report on specific issues. This is quite revolutionary, but in a way sits within the philosophy of open tax policy that New Zealand has adopted through what we call our generic tax policy process.

This open approach to developing tax policy is widely regarded as world leading by other jurisdictions. The proposed Tax Principles Act is not inconsistent with the existing approach. The intention is there will be consultation later this year and following that a bill would be introduced once the principles had been agreed and the reporting requirements had been established.

The resulting bill would be enacted before the end of the current parliamentary term, i.e. just in time for next year’s election. The proposal caused quite a stir and there’s plenty of good reading on it. Bernard Hickey has a very good summary of the matter.

It’s also quite rare certainly to see Ministers of Revenue philosophise in quite a public way. David Parker referenced Thomas Piketty’s seminal work, Capital in the 21st Century. He also acknowledged the very regressive nature of GST. Somewhat controversially he noted that because GST in transactions between GST registered businesses essentially zeros out and is a final tax for those who are not GST registered, it many ways it falls on labour earners.

As he put it, “GST is really paid out of our earnings when we spend it. In economic terms, GST is mainly a tax on labour income. Who pays that cost?”

The Minister noted we have limited data on the overall rate of GST paid by New Zealanders, either by income or wealth decile. So he’s asked Inland Revenue to gather data and to provide feedback on this. I suppose from a political viewpoint this hints that potentially if there are changes to a tax mix at a later date, something may be done in relation to GST as it impacts lower income earners.

All this kicked up quite a stir. When I appeared on Radio New Zealand’s the Panel following the speech, the panellists expressed some shock about the fact that we don’t really have data about how wealthy people are. I think the reason for this, which wasn’t discussed by Minister Parker, is that it’s probably largely the unintended consequences of the abolition of stamp duties, estate and gift duties, and the absence of a general capital gains tax.

In other jurisdictions which have some or all of those taxes, this gives a reference point when a transaction occurs as to what wealth is held and by whom. Incidentally, the disclosure requirements regarding trusts I discussed last week although they are primarily an integrity measure, they also represent, in part, an attempt to gather some data about wealth held in trusts and help fill the gaps in Inland Revenue knowledge.

With National and Act already putting out their tax proposals, it looks like tax will feature quite heavily in next year’s election. So it’s very much a case of let’s watch this space.

Moving on, today is the due date for submissions on Inland Revenue’s discussion document, Dividend Integrity and Personal Services Income Attribution. This contains a couple of controversial proposals.

Firstly, that sales and share of shares in a company with undistributed retained earnings would trigger a deemed dividend.

And secondly, changes to the personal services income attribution rules, which would mean more income would be attributed to a primary income earner.

Now, neither of these proposals have gone down particularly well and to describe them as controversial would be a bit of an understatement. The personal services attribution rules, in fact, may well have a very much wider effect politically than the Government might want to see.

Brian Fallow, writing in a very good column in last week’s New Zealand Herald, pointed out that the attribution rules, if enacted, would affect very large numbers of small businesses quoting former Inland Revenue Commissioner Robin Oliver “It is likely to catch tradies — a plumber, say, or a landscape contractor — with a van and some equipment and just themselves or one employee doing the work,”

And Oliver raised the question, is this really appropriate? I expect a lot of submissions on this paper, and I urge you to do so because as you can gather from comments made by Oliver, it could have a quite potentially significant impact for the SME sector.

I personally think the proposals go too far. And incidentally, one of the reasons that the proposals have been made comes back to a longstanding topic in this podcast and something that wasn’t directly referenced by Minister Parker in his speech, the absence of a general capital gains tax.

Inland Revenue proposes any transfer of shares by a controlling shareholder to trigger a dividend where the company has retained earnings. In jurisdictions which have capital gains tax, that transaction is normally picked up as a capital gain. But as we don’t have a capital gains tax Inland Revenue is proposing a workaround which I don’t think is appropriate one.

I think there are other alternatives they might want to consider. The proposals on the personal services attribution rules are an integrity measure. They build on the Penny Hooper decision relating to surgeons from ten years ago.

They are understandable, but I believe go too far and are probably targeting the wrong group of people. Moving on Inland Revenue has a useful draft interpretation statement out considering what is the meaning of building for the purpose of being able to claim depreciation.

This has actually become quite relevant because back in 2011 the depreciation rate on buildings was reduced to zero. But in 2020, in the wake of the pandemic, the depreciation rate for long life non-residential buildings was increased from 0% to 2% if you use a diminishing value basis or 1.5% if you’re using straight line method.

What this draft interpretation statement explains is the critical difference between residential and non-residential buildings. it replaces a previous interpretation statement released in 2010 which has had to be updated following an important tax case in 2019 involving Mercury Energy.

A building owner will be able to claim depreciation for a ‘non-residential building’ and that can in some cases have some residential purposes. Generally, it’s aimed at commercial industrial buildings and certain buildings such as hotels, motels that could provide residential commercial accommodation on a commercial scale. It’s a useful explanation and comments on the draft close on 2nd May.

Chump change for FATCA

And finally, a quite extraordinary story from the United States, where it has emerged that a very important tax act, the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, better known as FATCA, hasn’t generated as much income as was expected when it was introduced in 2010.

The projection was that over the ten years to 2020, it would raise about US$8.7 billion US. The US equivalent of Inland Revenue, the Internal Revenue Service, (the IRS) spent US$574 million implementing FATCA. But according to a report just released, all the IRS can show for all that money invested are penalties totalling just US$14 million.

Now, that’s quite extraordinary. And this is important from a New Zealand perspective, because FATCA represents a huge compliance burden for all US citizens who are required to file tax returns, even if they may be tax resident in another jurisdiction.

FATCA was the template for what became the Global Common Reporting Standards on the Automatic Exchange of Information. The rest of the world looked at FATCA and thought, “That’s a good idea. We’d like to have some information about what overseas accounts our taxpayers have”. And so, the CRS, as it’s known, was introduced and has been in force now for about four years.

I would hazard a guess that Inland Revenue probably gathered well in excess of US$14 million as a result of the introduction of CRS. But to come back to a point that David Parker made about politics and tax being inseparable. One of the reasons that the IRS has done so badly is that the Republican controlled Congress won’t give it the money to do its job. And that situation doesn’t look likely to change.

As David Parker said, politics and tax are inseparable. And we’re going to hear plenty more about the two in coming months.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

2 Aug, 2021 | The Week in Tax

- Time for a more generous approach to working from home allowances

- Tax agencies stepping up scrutiny of crypto-assets

- Former Treasury Chief Economist takes a swing at the Government’s tax policy.

Transcript

A couple of weeks ago, I reported that the Inland Revenue main office in Wellington had been closed and the staff were working from home as a result of a potential earthquake risk which had been identified.

There’s still no timeline as to when Inland Revenue staff, almost over a thousand of them, will be able to return to the office. In the meantime, they’re working from home. And the question has now popped up “Well, how about a bit of reimbursement for extra costs like heating and broadband?”

Now, apparently, Inland Revenue response has been “You’re saving money by working from home. You don’t have to pay for commuting, lunches and all the rest”. But the Public Sector Association is saying, “They have to work from home through no fault of their own.” And maybe it’s time that Inland Revenue recognised that and reimbursed them for it.

One Inland Revenue staff member has noted the argument that he was saving money on commuting costs doesn’t wash, because as he put it, “the five dollars a day I spend travelling in and out of work has never been deemed by Inland Revenue as a work-related expense. It’s a personal expense and it’s not claimable.”

Now, what this points to is a grey area which requires a mix of better tax policy which lays out some better guidelines and perhaps employers as well coming to the party. The position is, as I set out last year, when this whole thing became very, very relevant when we were all working from home during the first lockdown, is that employees cannot claim a deduction for home office expenses. They are meant to be reimbursed reasonable costs by their employer. This apparently seems not to be happening generally and it seems Inland Revenue is also reluctant to do this.

There was a determination issued during last year which covered the pandemic, which said that an employer could pay an allowance to an employee working from home that covers general expenditure and up to $15 per week would represent as exempt income. But $15 a week is pretty low with broadband costs and heating costs.

So the question was raised back then and it’s now back on the agenda again in a slightly more ironical context that we perhaps need to be setting out better guidelines. It occurs to me, for example, in the film industry, I understand per diems have been agreed of around $50 per day for contractors working in the film industry. And that’s taken to be a reasonable estimate of the costs they would have incurred.

The position I’m coming to here is Inland Revenue perhaps needs to grasp the nettle and issue more determinations which are more generous in scope and make it clear that for employers who pay these allowances, the extra allowances will be deductible, and the expenses will be non-assessable for employees.

Working from home does shift some of the costs to the employee. And I think it’s only fair that they get reasonably reimbursed. The legislation is in place, but I think it seems clear that the correct practise isn’t always understood and followed by employers. So maybe setting out new actual monetary limits would be a better approach going forward, even if Inland Revenue seems rather reluctant to do that.

Everyone is looking at cryptoasset taxes

Moving on there is increasing scrutiny of the cryptoasset world, and it’s tied into tax authorities wanting to get a better understanding of people’s assets, plus suspicion that people are using virtual assets to evade tax and also that cryptoassets are part of illegal activities and money laundering.

So as part of that, earlier this week, the United Kingdom Treasury announced a proposal that will require any virtual asset transfer of above £1,000 to be accompanied by detailed personal information of both the originator and the beneficiary.

This is tied into proposed amendments to money laundering legislation required to keep the UK’s regime in compliance with the recommendations of the Global Financial Action Task Force. The Financial Action Task Force said in July 2019 anti-money laundering legislation should cover cryptoassets. Putting the legislation in place has always taken a little bit of time.

Anyway, this is another sign of the increasing attention that tax authorities and authorities generally are paying to virtual cryptoassets.

Over in the United States the Internal Revenue Service, in conjunction with the New York State U.S. attorney’s office, has been briefing experts on the latest U.S. government enforcement efforts related to virtual currencies and cryptoassets.

As of April 2021, the IRS has joined its civil and criminal cryptocurrency units through Operation Hidden Treasure. Its Fraud Enforcement Office and Criminal Investigation Units are working with international law enforcement and crypto industry experts to root out tax evasion. And apparently, these include something called John Doe summonses, which sounds pretty sinister, and no doubt will pop up on some American TV show in due course and be explained to us.

The US Federal tax returns, Form 1040, now includes a question on virtual currency income, and it’s actually at the top of the form. That’s deliberately designed in order to make it easier to prove the knowledge and willfulness element for criminal cases in this matter.

So what we’re seeing is a trend all around the world of really amping up the scrutiny of cryptoassets. It’s a fast-moving field and the tax treatment isn’t always as clear as it could be. But Inland Revenue here is continually issuing guidance on the matter. And people need to pay attention to this. You should expect that the tax authorities will have some idea of your cryptoassets holdings and therefore you should follow the law and file returns as appropriate.

Facing up to unintended consequences

And finally this week, a couple of things in relation to the ongoing arguments over the Government’s interest limitation rules. Firstly, Inland Revenue has issued a very useful precis of all the questions and answers relating to the interest limitation rules and bright-line tests.

At 22 pages it’s a much more digestible document than the main discussion document. And of course, Inland Revenue is still working through all the submissions. So it’s a useful one stop shop to go through and get an idea of what’s been said so far. However, you should not take what’s in this Q&A as actual policy. They’re still working through it and the final version still has to be signed off by the Minister of Revenue and Cabinet.

But meantime, Norman Gemmell, who is the chair in public finance at Wellington School of Business and Government, Victoria University of Wellington, and former chief economist at New Zealand Treasury has come out with a working paper entitled What is Happening to Tax Policy in New Zealand and is it Sensible?

It’s a very quick read about 14 pages which looks at the increase in the top income tax rate and the housing package, that is the interest limitation rules, increased bright-line period and other related matters. Basically, it takes the view that both represent ad hoc responses without a coherent strategy. It notes that these were pushed through very quickly based on limited analysis and against most official advice on the matter as to how to deliver on the Government’s objectives.

And in Gemmell’s view, there are potentially serious unintended consequences. In particular, the coherence of the tax system is at risk, and it’s not an unreasonable argument. In fact, someone quipped that’s a statement of fact not an argument,

But this comes back to what I said last week, that when you look at where there is incoherence in the tax system, it keeps coming back to the question of the taxation of capital and of property in particular. We keep fencing around this issue and the unintended consequences of doing so, force further unintended consequences of the actions taken to try and remedy that.

There won’t be an easy answer to this solution until that nettle is very firmly grasped and the politicians put the politics aside and look at how exactly are we going to achieve a coherent tax system and address the issues of diversion of resources away from productive assets, inequality, and housing affordability.

All of those require a comprehensive approach and taking a different approach to what we’ve been doing up to now. The latest patches may work, perhaps, but they come with unintended consequences as Mr Gemmell points out.

That’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients. Until next week ka kite āno!