25 Jul, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Depreciating buildings

- Who are taxed the heaviest?

- The OECD says housing should be taxed

Transcript

Inland Revenue has released Interpretation Statement IS 22/04 on claiming depreciation on buildings. Critical to this issue is determining the meaning of a “building” for depreciation purposes and the distinction between residential and non-residential buildings. The Interpretation Statement addresses this issue when it sets out when depreciation may be claimed for non-residential building and also for some fit outs. It confirms that no depreciation is available for residential buildings.

The Interpretation Statement then sets out where you can find the right depreciation rate for buildings when fit outs attached to buildings may be depreciable. How to treat an improvement of a building for depreciation purposes. And then finally, what happens when the building is disposed of or its use changes?

To recap, depreciation for all buildings was reduced to zero, with effect from the 2011-12 income year. Back in 2020 as part of the initial response to the pandemic, the Government reintroduced depreciation for non-residential buildings with effect from the start of the 2020-21 income year. Generally, the depreciation rate is 2% on a diminishing value basis, or 1.5% on a straight-line basis. Some other depreciation rates may be used where the building has a shorter than normal useful economic life. Examples would be barns, portable buildings or hot houses. Additionally, it’s possible to claim a special rate if the building is used in an unusual way.

Now for depreciation purposes “building’ retains its ordinary meaning which means anything that is structural to the building or used for weatherproofing the building. The Interpretation Statement emphasises that whether a building is residential or non-residential is an all or nothing test. If the building is non-residential depreciation is available, otherwise not, there’s no apportionment.

Residential buildings are any places mainly used as a place of residence. This includes garages or sheds included with that building. Places used as residential residences for independent living in retirement villages and rest homes are residential buildings are is short stay accommodation where there’s less than four separate units.

On the other hand, non-residential buildings include buildings used predominantly for commercial and industrial purposes, but not residential buildings. This also includes hotels, motels, inns, boarding houses, serviced apartments and camping grounds. Retirement villages and rest homes where places are not being used for independent living are non-residential buildings as is short stay accommodation where there are four or more separate units.

If improvements are made to a building, you must treat it as a separate item of depreciable property in the first tax year. Then you can either continue to treat it as a separate item of depreciable property or simply add it to the building by increasing the adjusted taxable value of the building.

In some cases, a fit out can be separately depreciated depending on the nature of the building and the nature of the fit out. Where the fit out is considered structural to the building or used to weatherproof the building it must be treated as part of building and not depreciated separately. Fit outs are depreciable in a wholly non-residential building and sometimes in a mixed-use building. But remember, the key point is that depreciation is not available under any circumstances for a residential building. So overall, this is a useful Interpretation Statement and is also, as has become the norm, accompanied by a very handy fact sheet.

The agencies tackling organised crime and its tax evasion

Moving on, last week I discussed a suggestion by ACT Party leader David Seymour to use Inland Revenue against the gangs. I looked at the powers available to Inland Revenue and discussed how practical his proposal was. To summarise, Inland Revenue has extensive powers which would be useful in tackling gangs and organised crime. However, this is a resource intensive approach which probably in Inland Revenue’s view, would divert its attention from other areas it considers equally important.

This prompted some discussion in the comments section and thank you again to all those who contributed. As I said, my view is Inland Revenue probably thinks other agencies, such as the Police, are better suited for this activity. But it will cooperate with those agencies. Its annual reports make clear they pass information to other agencies. So Inland Revenue is probably working on this matter in the background.

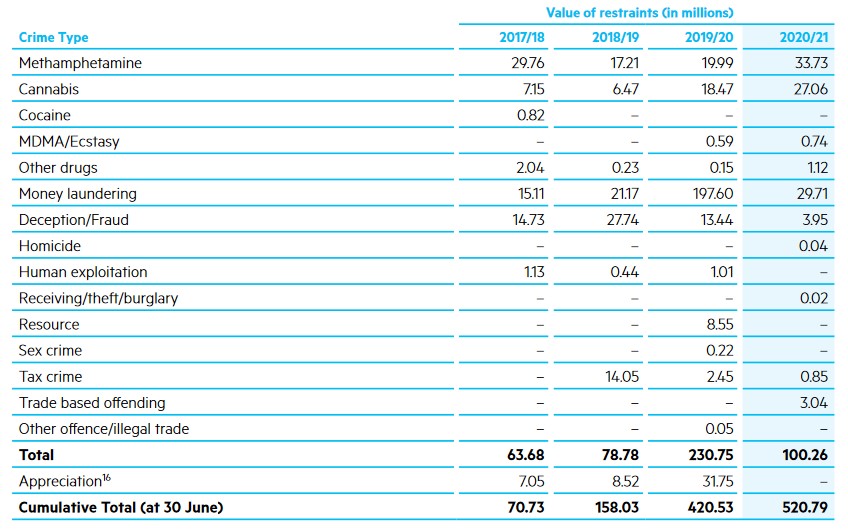

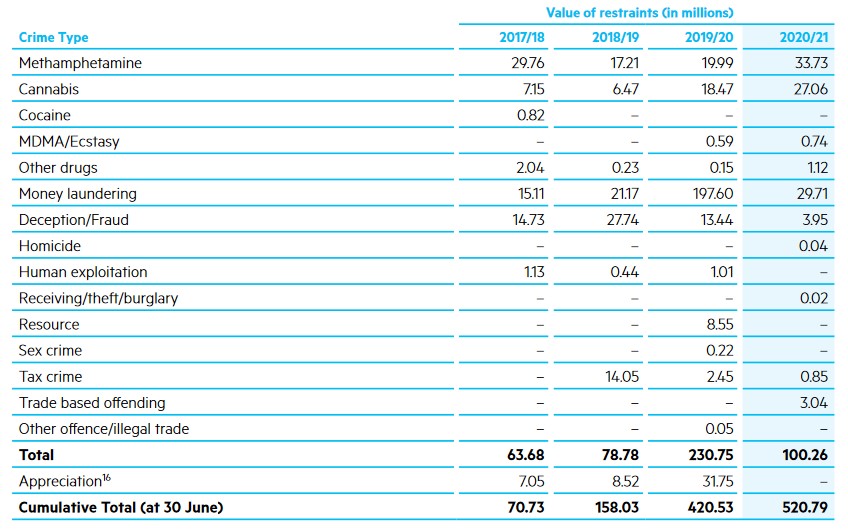

It was interesting just to take a look to see what other agencies were doing in this space and get a gauge of what’s happening. A key tool for the Police is the use of restraining orders to seize assets. According to the Police’s Annual Report for the year ended 30th June 2021 the value of restraints for the year totalled just over $100 million, including nearly $30 million seized from anti-money laundering.

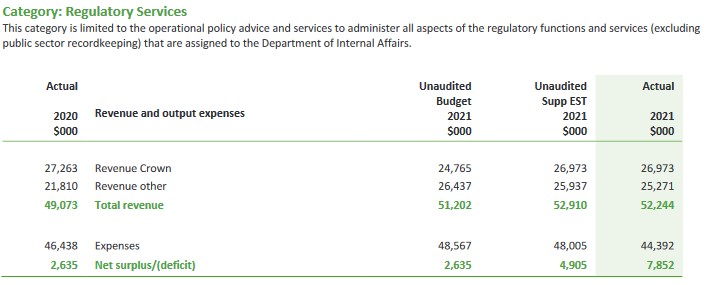

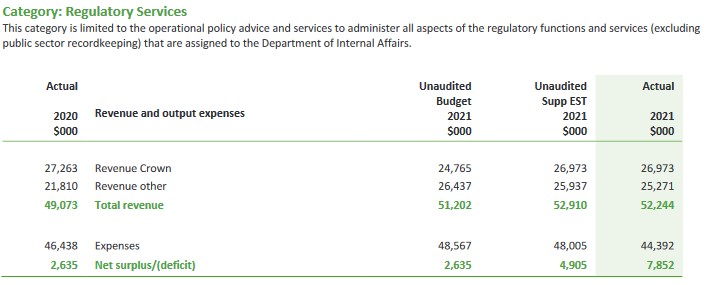

The Department of Internal Affairs also has responsibilities for anti-money laundering, as it’s a key regulator on that. Its Annual Report to June 2021 indicates that perhaps it could do more in this space, as its budget for its regulatory services for the year was set at $52 million, but it only spent $44 million.

And then when you look at the DIA’s performance metrics, such as desk-based reviews of reporting entities, it’s supposed to be targeting between 150 and 350 such reviews annually, but managed only 219 for the year, up from 198 in the previous year. And on-site visits were meant to be somewhere between 70 and 180 but came in at 79. To be fair these were probably disrupted by the impact of COVID 19.

Still, there are other agencies involved in pursuing gangs including Customs who will also be very interested. Inland Revenue will be playing a role, it shares information with these other agencies. So even if it’s not wielding a very big stick publicly, it’s working in the background.

The interaction of tax and abatements on social assistance

Now tax has been in the news a lot recently with the election coming up even though it’s still just over a year away probably. National and the ACT Party have both set out they would proposed some tax cuts. Last Saturday, Max Rashbrooke, a senior associate at the Institute of Governance and Policy Studies, who has written quite a lot on wealth and taxation put out some counter proposals to National and ACT’s proposals.

He suggested that really the focus should be on middle income earners. And he made a suggestion, for example, that we could have a $5,000 income tax free threshold, something we see in other jurisdictions. Britain’s is just over £12,500, Australia’s is A$18,200 and the US has a slightly different thing. It gives you a standard deduction of US$12,000. But anyway, let’s take that comment elsewhere. And Max suggested that something could be done in that space.

But it got me thinking about the question of who does actually pay the highest tax rates in the country. And the answer isn’t those on over $180,000 where the tax rate is 39%, it’s actually more around $50,000 mark if those people are receiving any form of government assistance, such as Working for Families. If they have a student loan as well, then an additional 12% of their salary after tax gets deducted.

The interaction of tax and abatements on social assistance, such as the family tax credit and parental tax credit can mean in some cases, the effective marginal tax rate for some families is more than 100% on every extra dollar they’re earning. This is an issue which the Welfare Expert Advisory Group touched on, but the Tax Working Group wasn’t allowed to address. But it’s a huge problem.

Take, for example, someone earning $50,000, just above the $48,000 threshold where the tax rate goes from 17% to 30%. And that, by the way, is the rate where I think we need to focus our attention on adjustments to thresholds and tax rates. At that level every extra dollar they’re earning is taxed at 30%. If they’ve got a student loan then they pay a further 12%. If they have a young family and are receiving Working for Families tax credits, then these are abated at 27%. Incidentally, the abatement threshold is $42,700. So that means that that person is on a marginal tax rate of 69%. Definitely not nice.

Then there’s a separate credit, the Best Start tax credit which has a separate abatement regime in addition to the Working for Families abatement regime I just explained. So that’s why people could be suffering an effective marginal tax rate of over 100%.

In my view, this is the area where we really need to be thinking about changing the tax system, because to compound matters, governments have been very cynical about not adjusting thresholds for inflation, something I’ve raised repeatedly in the past.

Working for Families thresholds were adjusted for inflation every year until National was elected in 2008. Starting in the 2010 Budget they started freezing thresholds. They also increased the abatement rate which used to be 20% and is now 27%. The current Working for Families abatement threshold is $42,700, which is less than what someone working full time on the minimum wage will earn annually

Looking at student loans the threshold where repayments start in 2009 was $19,084. That is now $21,268 but for a long period of time under the last government it was frozen. National also increased the repayment rate from 10% to 12% in 2013.

So this is an area where governments of both hues have been really quite cynical in my view, and where a lot of serious thought needs to go in about trying to address the inequities that have arisen. The Welfare Expert Advisory Group suggested the abatement rate should be 10% on incomes between $48,000 and $65,000, then increase to 15% before rising to 50% on family incomes over $160,000. (Yes, large families with that level of income could be receiving social assistance in some instances).

There’s a lot of work to be done in this space and inflation adjustments to thresholds is something that should be done anyway. But I think we need to think carefully around the thresholds and how the interaction with social assistance works. At the moment we’re not getting that sort of analysis from either any of the main parties and that’s disappointing, as it’s something that really needs to be addressed.

Why the FER deals with recurrent taxes better

And finally this week, just hot off the press is an OECD report on Housing Taxation in OECD countries. This makes for some interesting reading. Briefly, the report is concerned about how housing wealth is mostly concentrated amongst high income, high-wealth and older households. And in some cases, they believe that a disproportionately large share of owner-occupied housing wealth is held by this group. There’s been unprecedented growth in house prices, not just in New Zealand, but across the whole OECD, making housing market access increasingly difficult for younger generations.

In terms of suggestions the OECD believes that housing taxes are “of growing importance given the pressure on governments to raise revenues, improve the functioning of housing markets and combat inequality.” The report notes the way housing taxes are designed often reduces their efficiency. Recurrent property taxes, such as rates, are often levied on outdated property values, which significantly reduces their revenue potential. This also reduces how equitable they are because where housing prices have rocketed up, people are underpaying based on current values. And conversely people in places where prices are falling or have been stagnant are paying more relative to those in richer areas.

One of the suggestions the report makes is that the role of recurrent taxes on immovable property should be strengthened, by ensuring that they are levied on regularly updated property values. And this is one of these reasons why Professor Susan St John and I have been promoting the Fair Economic Return approach. One of the strongpoints of our proposal would be strengthening the role of recurrent taxes.

Capping a capital gains tax exemption on the sale of a primary residence

Another proposal would not at all popular. It is to consider capping the capital gains tax exemption on the sale of main houses so that the highest value gains are taxed. This should strengthen progressivity in the system and reduce some of the upward pressures. This is what happens the U.S. There is a US$250,000 exemption on the main home per person, and above that the gains are taxed. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t have a similar type exemption here if we want to introduce a capital gains tax. But as I said, that would be particularly unpopular.

The OECD also believes there should be better targeted incentives for energy efficient housing, because housing, according to this report has a significant carbon footprint, maybe 22% of global final energy consumption and 17% of energy related CO2 emissions.

So, there’s a lot to consider in this report, and we come back to it and consider it in more detail. But again, it sort of comes to this point we’ve talked about repeatedly on the podcast, the question of broadening the tax base and the taxation of capital. These issues aren’t going to go away, particularly when you consider, as I mentioned a few minutes ago, how very high effective marginal tax rates are paid by people on modest incomes who may not have any housing. No doubt we’ll be discussing all these issues sometime again in the future.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

18 Jul, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Using tax law against gangs

- OECD tax coordination on MNCs

- Ireland’s tax risks

Transcript

Last Saturday, the ACT party leader David Seymour appeared on Newshub Nation and suggested that Inland Revenue be used to deal with the gangs.

He believed the powers currently being used by Inland Revenue as part of its high wealth individual research project could equally be applied to deal with the gangs. It did make for some entertaining viewing, as interviewer Rebecca Wright was more than a little incredulous at the suggestion that gang members wearing patches would happily submit to filling out questionnaires. On the other hand, the notorious mobster Al Capone, was ultimately jailed for tax evasion so the use of Inland Revenue against organised crime is not that unreasonable a suggestion.

Mr. Seymour does seem to have misunderstood the nature of the powers currently being used by Inland Revenue as part of its high wealth individual research project. Those powers have been deliberately limited so that the information gathered is solely for research purchase purposes. They are therefore more prescribed than the general powers available to Inland Revenue. I also think Mr. Seymour was overstating how much of a sanction non-compliance with the high worth individual research project would be.

Now Inland Revenue does indeed have some extensive powers of information request and where appropriate, search and seizure. And if you want an example of how it can apply those rules that can be found in the case of Tauber v Commissioner Inland Revenue.

In this case, Inland Revenue was investigating a former accountant who it believed was suppressing income. After its initial information requests were not satisfactorily answered in its view, Inland Revenue then decided to use the powers available to it under Section 16 of the Tax Administration Act. It carried out simultaneous search and seizure operations at six separate locations, including a boat shed.

Mr Tauber responded by making an application for judicial review, claiming that the various Section 16 warrants were too widely drawn and not specific enough. The application also questioned whether the searches were necessary for carrying out the Commissioner’s functions and if the searches were carried out in an unreasonable manner. Unfortunately for Mr Tauber and the other claimants the courts upheld Inland Revenue’s use of its powers.

The case illustrates the extensive powers available to Inland Revenue. However, what it also illustrates is that applying those powers is a very intensive operation requiring a considerable number of resources. If you’re raiding six properties simultaneously with teams of investigators, you’re talking about an operation which may have involved somewhere between 40 and 50 people. Now if you think about dealing with gang members Inland Revenue would also want to be raiding several premises simultaneously. Therefore, that would require considerable resources from it and no doubt police officers to be available in case matters escalated.

It’s therefore questionable whether Inland Revenue would actually have the resources to carry out major investigations into gangs. And although tax evasion is a criminal offence, Inland Revenue would probably be of the view that the powers available to police and other authorities under the anti-money laundering legislation, which have been strengthened this week, mean those agencies are more appropriately deployed to deal with organised crime.

This isn’t to say that Inland Revenue wouldn’t pass up the opportunity to investigate tax evasion involving gangs if it felt considerable sums were involved. But as the Tauber case shows, using its full range of investigatory powers requires considerable resources, which ultimately, I think, Inland Revenue might feel better used elsewhere. In other words, “Nice idea, but yeah nah.”

Update on OECD tax reform

Moving on, the OECD delivered its latest update on the status of the international tax reform agreement to G20 finance ministers and central bank governors a couple of weeks ago. This included a progress report on the status of Pillar One, which is the proposal to ensure that market jurisdictions can tax profits from some of the largest multinational enterprises.

The OECD Secretary-General presented a comprehensive draft of what these proposed technical model rules will be for Pillar One. These are now going to go out for public consultation between now and mid-August. The intention then is to finalise a new Multilateral Convention by mid-2023 for entry into force in 2024.

In addition to updating the status of the Multilateral Convention to implement Pillar One, the Secretary-General’s Tax Report also gave an update on how an implementation of the OECD transparency agenda (the Common Reporting Standards on The Automatic Exchange of Information). And the latest update is that information on at least 111 million financial accounts worldwide covering total assets of nearly €11 trillion was exchanged automatically between tax administrations in 2021. And later this year, the OECD will finalise a new crypto-assets reporting framework, which will be included as part of the Common Reporting Standards. So things are moving ahead even if they’re going more slowly than people had expected.

In relation to the Pillar Two work, which introduces a 15% global minimum global minimum corporate tax rate, the technical work on that is largely complete and an implementation framework is to be released later this year to facilitate the implementation and coordination between tax administrations and taxpayers. All G7 countries, the European Union and several other G20 countries, along with several other economies, have scheduled plans to introduce the global minimum tax rules. New Zealand hasn’t reached that stage but consultation on the matter has just ended, so we may see something later this year.

IRELAND’S TAX RISKS

Now one of the ideas behind the Pillar Two global minimum corporate tax rate is to try and stop tax competition driving corporate tax rates lower. Now, one of the poster child’s for lower corporate tax rates is Ireland. And last week I mentioned Ireland’s strong GDP per capita growth in recent years. This appears in part to be a by-product of multinational and multinational investment in Ireland, attracted by Ireland’s low corporate tax rate of 12.5%.

Now tax is always full of unintended consequences and this week the Irish Finance Ministry highlighted a potentially huge downside of this policy for Ireland.

Apparently just ten multinational firms pay over half of Ireland’s corporate tax receipts. These are expected to be between €18 and €19 billion this year, up from an estimated €16.9 billion forecast just three months ago. And by the way, that’s nearly a five-fold increase in the last decade.

Now, on the face of it that all sounds good. But John McCarthy, the Irish finance ministry’s economist, warned that the fact that just ten multinational firms pay more than half of honest corporate tax, represents “an incredible level of vulnerability” for the Irish economy, as a shock, which impacted on the multinational sector would have severe fiscal implications for Ireland. I understand something like one in nine Irish employees are employed by multinationals such as Facebook, Google and Pfizer. Therefore, the fallout from a shock in this sector could be huge for Ireland.

Mr. McCarthy told reporters the level of concentration in such a small number of firms is something he has never seen in any other economy. He was therefore more worried about the overreliance on these types of firms than the impact of the global overhaul of corporate tax regimes could have on Ireland’s position as a hub for multinational investment. Ireland power. The same report estimates that Ireland’s tax take would be affected negatively by about €2 billion over the medium term.

Irish Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe then chipped in saying he has long shared the concerns McCarthy outlined. He said the best way to manage the risk was to return to the pre-pandemic position where corporate tax receipts are not used to fund permanent spending. This seems an incredible admission that a low corporate tax rate is actually not sustainable over the long term. So that’s something to pause to think about when you hear talk about corporate tax cuts.

By the way, these concerns of the Irish finance minister and the Finance Ministry might explain why Ireland didn’t oppose the proposed 15% global minimum tax rate. I suspect that on the quiet this represents an opportunity for Ireland to raise its corporate tax rate without too much fuss. It would be interesting to know the level of concentration here in New Zealand. I guess the big four Australian banks and the New Zealand Superannuation Fund would represent at least 20% of the corporate income tax take.

IRD BACK LIQUIDATING DEFAULTERS

Moving on, a quick follow up from last week’s items about Inland Revenue’s enforcement and collection activity increasing. As of 30th June 2021, 140,000 taxpayers had arrangements with Inland Revenue covering $3.7 billion of tax. Now, Inland Revenue would be keen to ensure those numbers don’t continue to grow. Historically, what it’s done is taken strong enforcement action including initiating liquidations. Apparently about 70% of all high court liquidations were initiated by Inland Revenue. However, during the pandemic, as part of its more sympathetic response, that number fell to just under 30%.

However, I’ve been informed that since April that there’s been a huge escalation in Inland Revenue activity in the High Court and liquidation proceedings. So that’s the clearest sign of Inland Revenue’s increased focus on debt collection and a clear warning to all those out there that if you if you’re in trouble you need to front up and try and make arrangements with the Inland Revenue before they take it further to the liquidator.

AWARDS FINALISTS

And finally, this week, the Tax Policy Charitable Trust has just announced its four finalists in this year’s Tax Policy Scholarship competition.

This competition is designed to support tax policy, research and thinking. Entrance is limited to those under the age of 35, and the intention is that people are asked to give ideas of proposals for reforms to our current tax system, to address potential weaknesses and unintended consequences of existing laws. Now there are three topics in this year’s competition: environmental taxation, tax, administration generally, or the powers granted to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue and to investigate for research policy purposes. (These are the powers that Mr. Seymour was referring to in his interview about tackling the gangs).

The four finalists are Daniel Doughty, a senior consultant with EY in Wellington. He’s proposing a small business consolidated reporting regime to simplify tax reporting for small companies. I think this is an excellent suggestion, so look forward to finding more about this. Our tax system expects a lot of administration from small businesses without really trying to adjust the compliance burden to help them with those processes.

The second finalist is Mitchell Fraser, a tax solicitor with Mayne Wetherell in Auckland. Mitchell is worried that the new powers granted to Inland Revenue for tax policy purposes may have unintended consequences. He’s suggesting alternative means to collect the information that’s wanted, including through Statistics New Zealand.

The third finalist is Vivien Lei, a group tax advisor with Fisher Paykel Healthcare. Vivien has got another interesting proposal to change New Zealand’s environmental practises by introducing an impact weighted tax regime. Under this model, organisations will be taxed on a net positive or negative impact on the environment. Now this is an area I’m very interested in and previous readers or listeners of the podcast will know that John Lohrentz, one of the runners up in the last competition, proposed a progressive tax on bio genetic biogenic and methane emissions in the agriculture sector. It’s therefore good to see there’s plenty of focus on this area.

And finally, there’s Jordan Yates, a senior tax consultant with ASB in Auckland, and he believes the tax policy landscape has been fractured and suffocated by political roadblocks. I don’t think he’s wrong there. Jordan’s proposing an independent statutory authority that would be responsible for the independent management of fiscal policy as it relates to the tax base. It’s an idea I’ve heard floated in other places and another one I look forward to hearing more about. This fracture is one reason why the Minister of Revenue, David Parker, has proposed his Tax Principles Act.

The finalists have all been asked to develop a 5,000-word submission on their proposal. They’ll then make a final presentation and answer questions at a function later this year in October, after which the winner will be announced.

This is a great initiative by the Tax Policy, Charitable Trust, and I look forward to hearing more about these proposals. And as we did with Nigel Jemson, the winner of the last competition and runner-up John Lohrentz we will hopefully have the prize winners on the podcast.

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week!

11 Jul, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- IRD targets overdue tax debt

- GST on directors’ fees

- RBNZ analyses housing

Transcript

Inland Revenue has begun taking more action on outstanding tax debt. It dialed back how hard it was pushing on overdue tax debt during last year in the wake of Covid-19. But in recent weeks, its activity has stepped up, and those involved with corporate reconstructions are seeing much more activity with Inland Revenue pursuing tax debt.

There are some reports that it’s particularly targeting the housing and construction sector, but that’s not necessarily the case, as I understand it. But the housing and construction industry has a record of nonpayment. Inland Revenue is particularly concerned about those companies or individuals not keeping up to date in relation to their GST and PAYE obligations. Inland Revenue’s longstanding view is that such receipts are held on trust (because they’re being withheld from the payees) and therefore the companies have no right to the payments and need to pass them straight through to Inland Revenue.

An Inland Revenue spokesperson confirmed they were taking more action adding “We give high priority to any business that has failed to pay employee deductions when due.” In the past Inland Revenue sometimes seemed quite extraordinarily slow in taking action with overdue PAYE. But if it’s boosted its efforts in this space that’s all well and good because following Gresham’s law, bad money drives out the good. And those conscientious employees and businesses that follow the rules and make the payments as required are being undercut by more unscrupulous operators.

In that context, what I’ve been told is that Inland Revenue is also upping its efforts in relation to developers who are claiming GST on land purchases, but then failing to declare the GST when they make the subsequent sales of the properties. In some cases, you also have what they call “Phoenix companies” where there’s a pattern of developers establishing companies which then fall over leaving unpaid tax debts. Inland Revenue got itself extra powers to try and deal with those matters. And I would expect that with its enhanced capabilities following completion of the Business Transformation programme, Inland Revenue should be on top of that situation.

As always with tax debt the key thing to do if you run into trouble, is talk to Inland Revenue. It is actually surprising how little tax debt can soon become unmanageable for people. Inland Revenue’s own research suggests that break point is as little as $10,000. This ties in anecdotally what I’ve seen.

The key thing is, if you get in front of Inland Revenue early, tell them that you have hit difficulties and want to arrange an instalment plan, they will be cooperative. Where they won’t be cooperative, and in fact they may look to take action and prosecute, is where someone persistently fails to meet their obligations in relation to paying over PAYE and GST and then tries to evade any responsibility by attempting to liquidate the company. Such scenarios increasingly will lead to prosecutions by Inland Revenue.

People will be surprised at how reasonable Inland Revenue can be. But to do so you have to be front up early, put all your cards on the table and you can then hope to get a reasonable hearing. Sometimes it doesn’t work out, but you would be surprised at how often these issues can be resolved.

And this also takes the stress away from people, employers and business owners who get into tax trouble quite naturally stress about the matter and often put their heads in the sand. It’s remarkable how much of a difference to stress levels it makes once you’ve spoken to Inland Revenue, and you find is this they are prepared to come to some form of arrangement. That’s dependent on a number of factors, the key factor being willing very early on to deal with the issue.

GST for directors’ fees

Moving on and still talking about GST, Inland Revenue has released some draft guidance for consultation on the treatment of GST for directors’ fees and board members’ fees. This covers a number of draft public rulings and is accompanied as well by a very useful fact sheet. I’m liking how Inland Revenue is sending out a lot of these fact sheets alongside the longer papers with detailed consultation, because the fact sheets of what you can put in front of clients as they are a good summary of the issues.

The rulings will cover directors of companies, board members not appointed by the Governor-General and board members appointed by the Governor-General or the Governor-General in Council. Basically, what the rulings say is board members or directors must charge GST on the supply of services where the director or board member is registered or liable to be registered for a taxable activity that they undertake, and the director or board member accepts a directorship or membership of a board in carrying on that tax taxable activity. Remember, liable to be registered means they are carrying out taxable supplies which over a 12-month period would exceed $60,000.

And the director or board member cannot charge GST on the supply of services where they are engaged as the director or board member in their capacity as an employee of their employer or they’re engaged in in that capacity as a partner in a partnership, or they do not accept the office as part of carrying on a taxable activity.

As I said, these draft rulings are accompanied by a fact sheet, which includes a very handy flowchart, these flow charts and fact sheets makes life a lot easier and more understandable for those affected. The proposed rulings are reissues of previous rulings on the matter. They’re fairly uncontroversial as they generally are simply restating the law, updating the statutory references and setting it out in a clearer and more understandable format for the general public.

Tax take up strongly

Now, this week, the Treasury released the government’s financial statements for the 11-month period ended 31st May 2022. And it all looks a lot better than what was being forecast in May’s Budget. Core tax revenue is $2.9 billion ahead of forecast just at just under at $98.9 billion. Now, the main reason it’s ahead of forecast is a higher than expected corporate income tax take which is $1.6 billion ahead of forecast. There’s also more tax from individuals which is $700 million ahead of forecast and PAYE collections are another $600 million ahead of the Budget forecasts.

The corporate income tax take for the 11 months of the year to date is just under $17.9 billion compared with a forecast $16.2 billion. Just for comparison, in the year ended 30th June 2021, the total corporate income tax take was $15.7 billion. So corporate profits look strong, and I think one or two economists might be pointing to whether that might be feeding inflation. But whatever its role is, I’m sure the Government will be grateful for the continued strong growth in the corporate income tax take. By the way, that increased corporate income tax take will also reflect the fact that the New Zealand Superannuation Fund will be paying substantially less tax this year than in 2021 because of the volatility in the financial markets.

Favourable winds for windfall taxes

Elsewhere in the world President Macron in France is under pressure to consider a windfall tax on some parts of the corporate sector where high energy prices have resulted in higher profits. Britain, you may recall, imposed a windfall tax on some oil companies, although it’s come with a potential subsidy which may dilute the impact of that. Windfall taxes have no real history in New Zealand, so are unlikely to happen here. But it is to see how other jurisdictions are reacting to questions of what they perceive as excessive profiteering.

Housing’s tax-free advantage

And finally, this week the Reserve Bank of New Zealand issued an Analytical Note on how the New Zealand housing market looks in the international context. What it does is compares facets of the housing market in New Zealand with those in 12 other developed countries[1] over the 30-year period from 1991 to 2021.

And it notes that several other economies, Australia is one, have experienced increasing house prices in recent years, but the rate of increase has been the highest here. Interestingly we have also seen the steepest decline in mortgage rates since the Global Financial Crisis and then almost the strongest increase in population. Apparently, although we’ve been ramping up construction quite dramatically in the past few years, the number of dwellings per inhabitant remains low and below the average for the OECD.

There was some mostly passing commentary in the note about the impact of tax. The paper does touch on the absence of a general capital gains tax commenting:

“Another feature of the New Zealand economy that may support higher housing demand is the absence of a comprehensive capital gains tax. New Zealand is unique in that aspect in the sample of countries we consider, fiscal authorities in other countries tax capital gains from asset sales at or close to the personal income tax rate.”

Being an analytical note, it doesn’t make any recommendations as to whether there should be increased taxes on housing, although the OECD has been for a long time pushing that point. It’s always interesting to consider the role of tax in our housing market and also whether the absence of the fact that housing is treated so generously for tax purposes means that investment is driven into that rather than into more productive sectors.

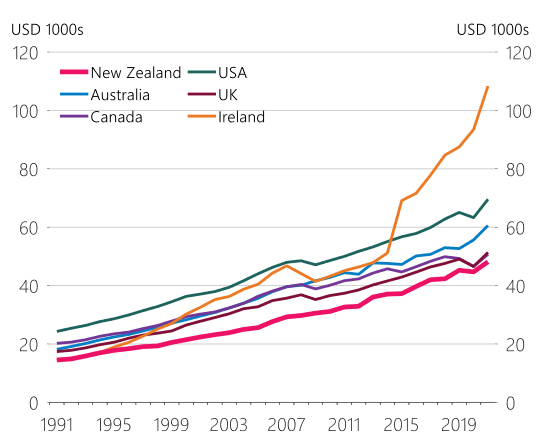

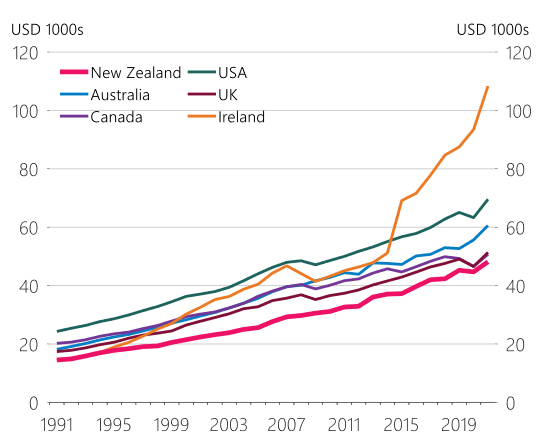

On that point, there’s a very interesting graph illustrating the surge in Irish GDP per capita over the last ten years or so, it’s really quite marked. The note comments that this surge

“was supported by high-performing multinational companies that relocated their intellectual property assets to Ireland attracted by lower corporate tax rates [12.5%] as well as Brexit-related uncertainty in the United Kingdom.”

Figure 4: per capita GDP in US dollars at current PPP

This Reserve Bank note reinforces my long held view that our favourable tax treatment of housing does divert funds away from productive investment and we need to change that treatment. As previously stated, my preference is for the Fair Economic Return approach Susan St John and I have proposed. .

Well, that’s all for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time kia pai te wiki, have a great week.

4 Jul, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Focus on international tax – getting serious about foreign income compliance

- A $70 million win over Big Tobacco.

- How are we going to pay for our roads in the future?

Transcript

It’s been a very busy week in international tax, beginning with the launch of Inland Revenue’s Compliance Focus on Offshore Tax.

This was accompanied by a number of presentations in Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. As part of the launch, Inland Revenue has released a couple of guides aimed at the general public, one on Offshore Tax Transparency and the other a Foreign Income Guide. Alongside those, there’s a Foreign income checklist and a flowchart on the rules relating to the transitional residency exemption. All this is aimed at the general public and written clear in plain English.

It’s good to see Inland Revenue have stepped up the focus in this area because we deal with quite number of clients in this space around their international tax obligations and there is a sometimes-surprising lack of knowledge. The main guide is the form IR1246 on Offshore tax transparency. It’s relatively short at 28 pages, including a glossary and as I said, is aimed clearly at the general public.

It begins with a little section at the start about “What your taxes pay for”. I think we’ll see more and more of this as Inland Revenue rolls out various publications as part of its compliance programmes. It’s a reminder of how much tax revenue is raised and where does it go. In case you’re interested Social Security and Welfare is the biggest single amount at $36.8 billion in the year to June 2021 with Health coming in second at $22.8 billion and education third at $16 billion.

This is adopted from similar initiatives we’ve seen in other tax authorities around the world, emphasising your taxes are for the common good and here’s where your taxes are spent and here’s how they may benefit you. So that’s a deliberate policy aimed at reminding people that tax is part of the price we pay for a civilised society.

The guide explains Inland Revenue’s role within New Zealand and then works its way through the various international obligations and standards. Some of this is pretty boilerplate and well known to tax agents and advisors but possibly isn’t so well known to the general public.

And the key point that Inland Revenue is really stressing is that it has access to a number of international exchange or information exchange programmes such as an exchange of information on request through one of the various double tax agreements or international exchange agreements New Zealand is a signatory to.

Then there’s a section which would make anyone with property overseas sit up and pay attention:

We annually exchange land data with many of our treaty partners. The data we exchange is a combination of this information we obtained from the land transfer tax statements, received land information in New Zealand and our own internal tax data. We also receive similar information from some of our treaty partners, which serves as good initial intelligence with an option to follow up with further exchange of information requests during the course of more in-depth compliance work.

We actually experienced this with one client when Inland Revenue requested whether we had disclosed income from property in the United States as they had received information from the US regarding the property. We had, but it was still illuminating to see how much Inland Revenue knew.

And then there are the spontaneous exchanges of information under FATCA (the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act), and the Common Reporting Standard on the Automatic Exchange of Information. Incidentally, the next exchange under the Common Reporting Standard is happening in September. There are the collection assistance agreements under several double tax agreements. This is something I don’t think people are really aware of Inland Revenue’s ability to ask overseas jurisdictions to go hunting for delinquent taxpayers and outstanding tax.

And then there’s the foreign trust regime’s reporting requirements. An interesting point here is that any information collected during the registration and annual return process of a New Zealand foreign trust is shared with the Department of Internal Affairs as the supervisor of trust and company service providers and the Financial Intelligence Unit of New Zealand Police. This information is shared because of their regulatory role in relation to anti-money laundering and countering the finance of terrorism.

The guide then runs through the various types of overseas income, and you can find more details in the Foreign Income Guide. This also includes taxpayers working remotely in New Zealand for overseas employers. This appears to be part of a new initiative.

One page in the guide has the header “Offshore is no longer off limits” and the guide explains Inland Revenue is involved with other international collaboration outside those agreements have already mentioned. These include the Joint International Taskforce on Shared Intelligence and Collaboration which apparently includes 35 of the world’s national tax administrations. There’s also the Study Group on Asia-Pacific Tax Administration and Research. I was not previously aware of these two organisations. So, you learn something every day.

Overall, this is a welcome and important initiative from Inland Revenue. People are now able to access easily understandable guidance as to their overseas income obligations. There’s an interesting comment that as a result of an initiative under the Common Reporting Standards, it received over 900 voluntary disclosures from people after they were advised Inland Revenue had received information regarding their overseas income. Voluntary disclosures happen regularly once people realise they have not complied with their obligations they come forward to rectify their errors.

“Leaving on a jet plane…”

Now, with the borders reopening and international travel resuming, Inland Revenue has decided to release for consultation a draft “Questions we’ve been asked” (QWBA) in relation to the deductibility of overseas expenses. This publication was actually delayed because of the pandemic as Inland Revenue thought it and we advisors might be busy elsewhere and really nobody was travelling.

This draft consultation covers the issue as to what extent can income tax deductions be claim for overseas travel costs other than meal costs? And basically, the answer is they can only to the extent they have a connection with deriving assessable income or carrying on a business. No deductions can be claimed for any part of the costs that are of a private or domestic nature or incurred in deriving exempt income. Now where the costs need to be impulse apportioned between deductible and deductible, then this must be done on a basis that is reasonable.

The draft QWBA doesn’t consider two issues: the treatment of a companion’s travelling costs which is covered by QB 13/05. And secondly, the deductibility of meal costs which is dealt with in Interpretation Statement IS 21/06.

This draft QWBA is a short document, 14 pages. It sets out the legislation, considers some of the current case law and then includes four practical examples covering various scenarios. The first is where there’s a both business and private purpose for travelling overseas. The second where there’s a business trip involving incidental private expenditure. Example three deals with someone is travelling overseas privately, but then realises on arrival there’s actually some business opportunities.

The final example deals with cancellation costs, which have not been refunded, something no doubt quite a few businesses experienced because of COVID 19. The example suggests that the cancellation fees are deductible because the costs were incurred in the course of, carrying on a business.

This is more useful guidance on a day-to-day issue which businesses and advisors are going to be encountering regularly now. It’s particularly opportune with borders reopening now, and international travel resuming.

Big Tech’s transfer pricing strategies

Now, last week I covered Google New Zealand’s December 2021 results. The same day Facebook also released its December 2021 results. These are the first results it’s released since December 2014. This is because Facebook has changed its model to now report on a country-by-country basis.

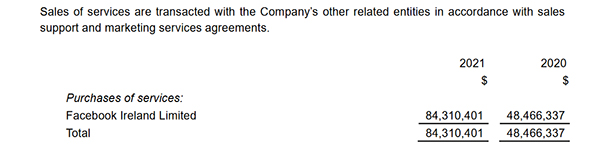

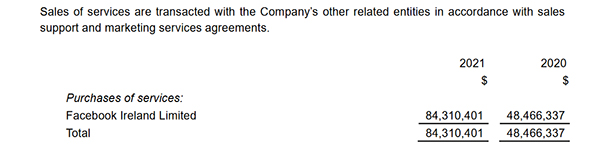

It’s interesting to see what’s gone on in the interim. Back in in 2014, Facebook paid $43,000 of tax on $1.2 million of revenue. This year, it’s reporting $6.5 million in revenue with a tax charge of $605,000. But the detail that’s of interest is what’s going on with its related party transactions as these give you a clue to the level of activity actually going on.

Facebook ‘s gross advertising income for the year to December 2021 was $88 million, which I have to say surprised me a bit as I thought it was higher than that. But anyway, these are the first concrete numbers we’ve seen for a while now.

$84 million was paid to Facebook Ireland for purchases of services.

Coincidentally, Facebook Ireland’s corporate tax rate just is 12.5%. So, you can work out yourself the potential saving that could represent for Facebook.

As I said in relation to Google’s results last week, it’s possible Inland Revenue is looking at this. We know there’s a lot of review activity going on in this space. Transfer pricing, audits and investigations do take some time and we got a clue as to how long and how they might play out result when British American Tobacco released its December 2021 results.

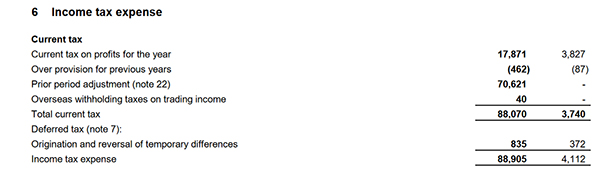

Included in these was a note that it had been engaged in an Advance Pricing Agreement (APA) process with Inland Revenue and the UK’s H.M. Revenue and Customs. This has been going on since March 2016 and it related to the combustible tobacco operations of the British American Tobacco Group. Agreement on the APA was finally reached in July 2021.

As a result, British American Tobacco New Zealand’s 2021 financial statements included a profit adjustment for prior years resulting in $70.6 million of additional tax payable for those prior years.

Now, the effect also of this agreement is that the tax payable for the December 2021 year rose from $3.8 million in the previous year to over $17.8 million. This increase illustrates the impact of the reduction in what overseas associates can charge. The turnover for New Zealand was roughly similar for both 2020 and 2021 at $247 million and $251 million respectively.

A win therefore for Inland Revenue and a little bit of a windfall as well for the Government. The case does show how long it takes to reach agreement on these issues.

Funding the road network

And finally, back in New Zealand, back in March the Government cut the fuel excise duty as a cost-of-living countermeasure. That was initially for a three-month period but is now being extended for a further two months until mid-August.

And this prompted David Chaston to take a look at the fiscal impact of this.

The National Land Transport Fund (NLTF) uses the funds from fuel excise duty and road user charges for the maintenance of country’s highway network.

The NLTF has some fairly big numbers going through it: in the year to June 2020, the total amount of fuel excise duty and road user charges amounted to just over $3.7 billion. In the June 2021 year, that total rose to just under $4.2 billion. However, as of April 2022, the total expected income from fuel excise duty and road user charges was about $23 million short of target. And obviously the longer the government keeps the fuel excise duty cut in place, the lower the income for the NLFT is going to be.

David therefore raised the issue about how are we going to fund the NLTF in the future? Remember that electric vehicles are currently exempt from those user charges, but thanks in part to the government’s clean car discount and the growing availability of electric vehicles, the number of EVs is rising. When does this exemption end? Longer term as the proportion of electric vehicles in the fleet rises, the amount of fuel excise duty will fall. This has to be an accelerating trend in order for the country to meet its emissions targets.

So, how is the NLTF to be funded in the future in order to maintain the highways? It seems to me there’s only two possible answers to that; firstly, increase road user charges, which means the exemption for electric vehicles must end, probably very soon. And secondly, and this is part of a wider decarbonisation issue, shift heavier traffic which increases wear and tear on highways to other modes of transport like local shipping and rail.

So that’s an interesting dilemma for any future government to be considering. I think any sort of environmental taxation moves in this space, are really more like behavioural taxes and therefore as the behaviour you are trying to discourage, the use of internal combustion engine vehicles declines, your revenue declines.

So longer term, some thinking has to go into how are we going to fund the maintenance of our highways? And it seems to me ultimately general taxation will need to become part of the mix. Rather than being specifically funded out of the National Land Transport Fund, the taxpayer will be paying a different way through contributions from the general tax pool.

That’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time. Ka pai te wiki, have a great week.

28 Jun, 2022 | The Week in Tax

- Shining some light on the impenetrable maze of the financial arrangements regime

- Inland Revenue brings estate agents into line

- Google NZ’s latest results show the need for international tax reform

Transcript

The financial arrangements regime is one of the most complicated parts of the income tax. It has huge scope but is not particularly well known. And until very recently there has been little practical guidance on the regime from Inland Revenue. Fortunately, all that is changing now. In the past couple of years, Inland Revenue has issued a series of Interpretation Statements which have clarified how the regime operates.

This week it’s released a revised draft Interpretation Statement on the critical issue of cash basis persons and how the regime applies to these people. Now, this is particularly important guidance because a person who is a cash basis person accounts for income and expenditure from a financial arrangements regime on a cash or realised basis rather than the at accrual or unrealised basis. The draft statement also sets out the adjustment that must be made when a person ceases to be a cash basis person and then has to switch to accounting for their financial arrangements income and expenditure on the accrual or unrealised basis.

There’s an accompanying fact sheet, so you don’t have to go through the whole full 33 pages of the Interpretation Statement. Page four of this fact sheet has a very useful flowchart, setting out process for determining if a person is a cash basis person. In summary, a cash basis person is someone who does not hold financial arrangements which exceed either of the following thresholds $100,000 of income and expenditure in the income year or the total value of these financial arrangements is under $1 million.

In relation to the $1 million threshold, the taxpayer must be below that threshold throughout the entire income year. So, if you cross it for just one day, that’s it, and you may be in the regime. If both those thresholds are exceeded the person cannot be a cash basis person.

Then there’s the second test you apply, if neither, or only one of the thresholds is exceeded. In this case you still have to check whether the difference between income and expenditure calculated on the cash basis, realised basis and under the accrual or unrealised basis does not exceed $40,000. This is what they call the deferral threshold. If it does, then the cash basis cannot apply. Now this $40,000 deferral threshold is often overlooked when people are considering whether or not they’re within the cash basis person. The Interpretation Statement has some good, worked examples how this applies.

If someone falls into or out of the cash basis status, they have to carry out a cash basis adjustment. And again, the Interpretation Statement has a good, detailed example. One of the issues that many people encounter is exchange rate fluctuations, which can put people unexpectedly into the regime and therefore have unintended consequences.

The classic examples I’ve seen are with people holding overseas mortgages against an overseas investment property and the fluctuation of the thresholds. Brexit in particular was one of those events that caught quite a number of people. Incidentally, this is perhaps why one of the examples here refers to the 2016-17 tax income year when Brexit happened.

The Interpretation Statement has a useful tip about financial statements subject to exchange rate fluctuations. It suggests identifying when the New Zealand dollar was at its lowest point compared to the foreign currency in the year and calculate the value of the New Zealand financial arrangements at that time. That’s a quick way of determining the highest possible value of the arrangement during the income year, assuming the principal hasn’t changed materially.

Paragraph 69 of the Interpretation Statement also includes some nice examples of why people might adopt the accrual basis from the outset. Doing so might resolve the problems around cash basis adjustments or they might want to actually bring the income or expenditure such as an unrealised exchange loss into account immediately.

The financial arrangements regime is actually another example where thresholds have not been frequently adjusted. These particular thresholds were last set at the start of the 1997-98 income year. They now catch far more people than were probably ever intended. Using the Reserve Bank calculator based on CPI, those absolute thresholds now would be $170,000 instead of $100,000, $1.7 million instead of $1,000,000 and the deferral threshold would be $70,000. If you use the Reserve Bank’s housing inflation calculator, then the income expenditure threshold would be $560,000, the absolute threshold for all financial arrangements would be $5.6 million and the deferral threshold $225,000. So whichever inflation indicator you’re using an adjustment is therefore well overdue.

The point here that frustrates me is that there’s a persistent theme across the tax system, where thresholds are not adjusted for inflation frequently enough. It’s a sneaky way for governments of both hues to collect additional revenue without too much notice. Quite apart from these financial arrangements regime thresholds, the income tax thresholds were last adjusted in 2010 as is well known.

The abatement threshold for working for families, that is the threshold above which abatement clawback applies hasn’t kept up inflation. By my calculation, I believe it’s now lower than what someone on minimum wage would earn. And the threshold for student loan repayments above which 12% is deducted from your income, that hasn’t been adjusted for some period. Governments really ought to be much more proactive about changing these thresholds. There’s actually a good political point here, in that doing so would de-politicize the issue. However, as I said, governments appear to quite like this sneaky increase in revenue.

Rant aside, it’s good to see guidance like this from Inland Revenue, the fact sheet is particularly useful. No doubt we’ll see more guidance on this area, but in the meantime, you should definitely have read this because this is a complicated regime and it catches far more people than you would expect.

Targeting real estate agents

Moving on, there was an interesting little piece in Stuff this week regarding the success of Inland Revenue’s campaign about real estate agents claiming personal expenditure when they shouldn’t as an attempt to reduce their tax bills. Inland Revenue advertised it was looking at estate agents’ expenditure which it thought was excessive.

We haven’t heard too many stories about who has been caught by this, but Inland Revenue took the view that focussing some attention on the issue would encourage others to behave. Basically, what was happening that some agents were understating income and overstating expenses. And it appears now over 90% of the tax returns for the March 2021 income year have been filed, Inland Revenue compared the results from that sector relative to earlier tax years and it has seen these trends reverse, particularly in relation to what it called private expenditure.

One of the one of the issues is claims for gifts, personal clothing and grooming and entertainment expenditure. And there was also under-reporting for GST purposes. Some people apparently used a net amount in their bank account for GST purposes. This is actually a really good example of Inland Revenue applying the blowtorch by saying “We have got the data we can match this and don’t think we’re not noticing what’s going on here”. So good to see on that.

There’s an interesting point here which I think Inland Revenue should issue some guidance on. And that is where someone who is working with clients and has to look professional, and therefore purchases smarter clothes for that role, what proportion may be claimable?

I remember a very famous case on this issue from my time in the UK: Mallalieu versus Drummond. A female barrister claimed a deduction for some very sombre, dark clothing that she wore only in court. She didn’t win her case, but the point still stands if you are purchasing clothes which are only use work to what extend is that deductible. And I think Inland Revenue should come out and clarify what it thinks about that.

Incidentally, Mallalieu didn’t involve the astonishing Section 189 of the Income and Corporations Taxes Act 1970. This allowed an individual to claim an expense for “keeping and maintaining a horse to enable him to perform the same or otherwise expend money wholly, exclusively unnecessarily the performance of said duties”. Yes, the UK tax legislation in 1970 (and actually again in the 1988 consolidation), had a reference for a specific deduction for a horse. That provision actually wasn’t updated until 2003. So, if you think our tax legislation is a bit arcane to spare a thought for the UK.

How much of Google’s NZ revenue escapes the NZ tax net

International tax has been in the news lately because concerns are starting to grow as to whether the tax deal signed last year by 130 countries, including New Zealand, is actually going to be implemented. Inland Revenue currently has a major issues paper out on the topic, submissions on which close next week.

The Revenue Minister David Parker was speaking to the Finance and Expenditure Committee this week. From his reported comments he expressed some concern about whether the so-called Pillar One and Pillar Two proposals would come into effect.

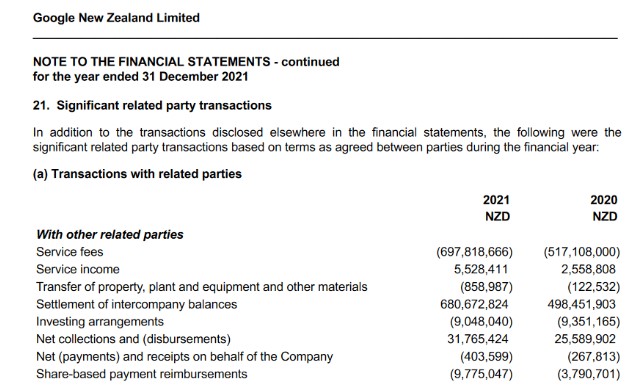

But the need for those rules to come into place was underlined, in my view, by Google New Zealand’s December 2021 results, which were published on the Companies Office website yesterday.

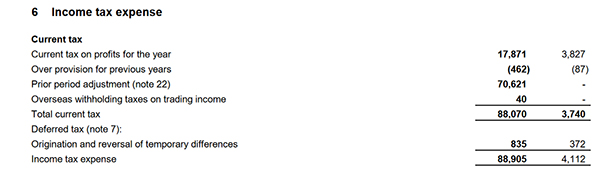

Google’s revenue, as reported for income tax purposes, rose from $43.8 million in 2020 to $57.8 million in 2021. Its pre-tax profit went from $10.2 million to just under $18 million, and Google ended up with $3 million corporate income tax for the year ended 31st December 2021 once you take into account timing adjustments.

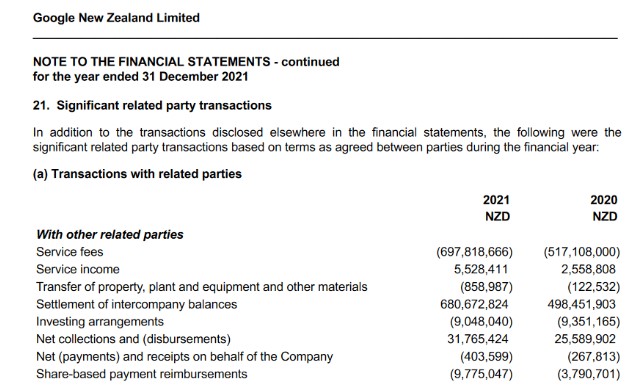

But what’s really interesting when you drill into the financial statements is what’s going on with related parties. The notes to the financial statements disclose the transactions with the related parties. We can see that the service fees Google New Zealand paid to other overseas companies in the Alphabet Group (the owner of Google) in the year amounted to $697.8 million. Now that’s up from $517.1 million in 2020.

This gives you an indication of the level of advertising revenue activity actually going through Google New Zealand. These service fees are perfectly valid although Inland Revenue will no doubt have its transfer pricing specialists run their eye over these fees. There may be some queries going on, we don’t know as the accounts are silent on that. But the level of activity here indicates how much advertising revenue is going through Google New Zealand and how much is being paid offshore as a legitimate deduction for income tax purposes.

But it shows the arrangements that are in place that enable substantial amounts of advertising revenue pass through Google New Zealand, but it finishes up paying only $3 million in income tax. It does pay a substantial amount of GST, according to the financial statements the GST payable has on 31st of December 2021 was just over $21 million. This would indicate a very significant level of taxable supplies deemed to be made in New Zealand. But it’s likely that the GST Google New Zealand is charging is probably also being claimed by New Zealand businesses. In other words, it’s largely a net zero-sum game.

Anyway, my hope is that the international tax deal will go through. There is politics being played in America, no surprises there, but also in Europe where the EU is trying to get unanimity amongst its 27 member states. It’s a question of “Watch this space” for developments. But Google gives you an example of why we would want to know more about what’s going on here and hope the deal goes through.

International Tax was a topic at the International Fiscal Association Conference held last week. As this was held under Chatham House rules, I can’t really say too much about it, but there were a lot of interesting topics from excellent presenters and a fairly lively debate on a number of topics including international tax.

Another featured topic was the controversial dividend integrity and personal services attribution rules, and that had probably the liveliest debate. The key takeaway for me from that particular session was a comment that these proposals show the limits of what can be done in the current tax system without a capital gains tax system. Because when you sit back, the cause of controversy there was that there were potentially capital transactions happening, which would be tax free under our present regime. However, Inland Revenue was looking at this and saying, “These transactions mean tax is not being paid”.

Now, the other take away I had, is that this tension is just getting worse and isn’t going to be resolved until the matter of taxing capital gains is resolved as well. I’m on record as supporting a capital gains tax. It probably is needed not so much as a revenue raiser but to preserve the integrity of the tax system. Because when you have such a hole in your base, it will be exploited. Incidentally, this means you can’t really argue, you’ve got your tax system is broad based. There are measures in place to deal with this, but we are talking about patches upon patches.

And so, this debate, which is going on for all the time I’ve been here in New Zealand but has intensified in recent years, is going to continue. At some point the issue will have to be grasped and resolved. No, it won’t be terribly popular. But if you want to maintain the integrity of the tax system, it seems to me that some form of capital gains tax is pretty near inevitable.

Well, that’s it for this week. I’m Terry Baucher and you can find this podcast on my website www.baucher.tax or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you for listening and please send me your feedback and tell your friends and clients.

Until next time Mānawatia a Matariki, enjoy Matariki!